- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

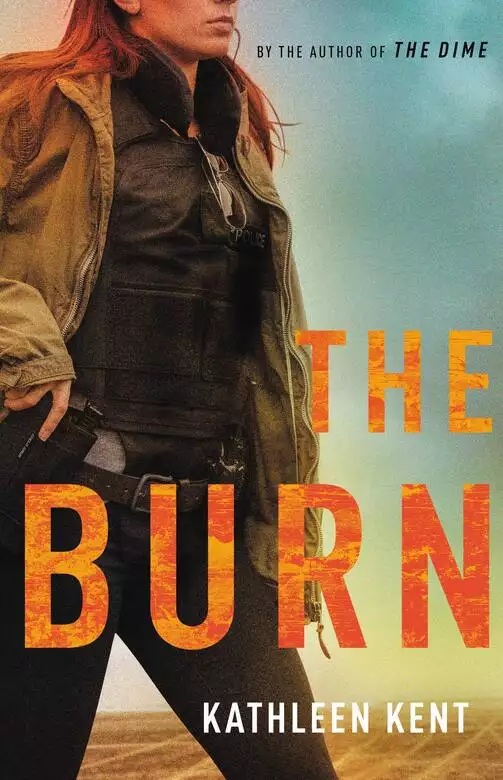

Synopsis

Rattled from a run-in with a cult and desperate for answers, Detective Betty Rhyzyk decides to go rogue—but her investigation leads straight into the dark underworld of the Dallas drug cartel.

There's not much that can make Detective Betty Rhyzyk flinch. But the wounds from her run-in with the apocalyptic cult The Family are still fresh, and she's having trouble readjusting to life as it once was. She's back at work as a narcotics detective, but something isn't right—at work, where someone has been assassinating confidential informants, or at home, where she struggles to connect with her loving wife, Jackie. To make matters worse, Betty's partner seems to be increasingly dependent on the prescription painkillers he was prescribed for the injuries he sustained rescuing her.

Forced into therapy, a desk assignment, and domestic bliss, Betty's at the point of breaking when she decides to go rogue, investigating her own department and chasing down phantom sightings of the cult leader who took her hostage. The chase will lead her to the dark heart of a drug cartel terrorizing Dallas, and straight to the crooked cops who plan to profit from it all.There's never a dull moment in Dallas, especially now that Det. Betty's back.

Release date: February 11, 2020

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Burn

Kathleen Kent

Friday, January 21, 1999

Alphabet City, Manhattan

Avenue D and 3rd Street

My Polish grandmother, to the end of her days, never trusted a man who smiled at the dark or wore white in wintertime. That was because Kostucha, the Grim Reaper, appeared at the moment of death, grinning like a dog at a feast and wearing a robe the color of snow.

I had never before that night met my brother’s partner, even though he was the subject of endless dinner conversations. My father knew Paul Krasnow, of course, because, like my brother, Paul was a detective at the 94th Precinct in Brooklyn. Paul was older than my brother, Andrew, by a decade, had been in the narcotics division for eight years, four of them undercover, and was rumored to be next in line for sergeant’s stripes.

Paul had an unbeatable record in Brooklyn: two dozen arrests of mid- to high-level crack dealers at Christmastime alone, close to half a million dollars in cash recovered, and over twenty fully automatic weapons taken off the streets.

Reluctantly, I had agreed to drive my brother and his partner into Manhattan so they could meet up with their CI to “settle some business.” According to Andrew, he had been working an undercover operation for half a year and the CI, who lived in Alphabet City, had something to show them. When I asked him why he couldn’t take his own car—or drive into the city in Paul’s brand-new Cadillac—he told me with a guilty smile that he had given his car to his girlfriend for the evening, and his partner didn’t want his car getting dinged.

“Great,” I had said. “So my hard-earned Toyota is the sacrificial lamb.”

I reminded Andrew that I had an academy exam in the morning, and that I couldn’t stay out all hours. Any of their pub crawling afterward would have to be done back in Brooklyn.

“Betty,” he had said, using the wheedling tone he always resorted to when he wanted to flatter or cajole me. “You are more of a man than I’ll ever be, and more woman than I’ll ever deserve. Do this for me,” he winked, “and I’ll slip you the answers to the policing ethics exam.”

The streets were slick with a frigid rain when the two of us picked up Paul in front of his apartment on Franklin Street. I took the Brooklyn Queens Expressway, crossing over the Williamsburg Bridge to Alphabet City. Despite my cautious driving, it took us less than forty-five minutes to get into Manhattan.

Paul sat in the back, but he might as well have been riding shotgun: he leaned forward the entire time, resting his arms on the front seat, talking constantly over my shoulder, asking nonstop questions about my time at the academy. Was it hard being a woman there? Did I want to get my detective shield? What division did I want to join? These questions seemed designed to make me think he was genuinely interested in my career in law enforcement, but I suspected they were to gain information about me that Paul could use to his advantage.

He never once cracked the inevitable cop-among-cops dirty joke—usually involving a drunken old lady or an inebriated stripper—so I assumed that Andrew had already given him the caution talk. But whenever I’d catch his reflection in the rearview mirror, his eyes were on mine like drill bits, despite the amiable banter.

I parked on the river side of Avenue D at 3rd Street, directly across from a Puerto Rican bodega. We were kitty-corner from the turn-of-the-century, five-story apartment building where the CI lived, in the heart of what was called, in Spanglish, “Loisaidas,” the Hispanic section of the Lower East Side. In the last ten years gentrification had begun transforming the neighborhood into an anglicized bastion of low crime and overpriced apartments and shops. There were still holdouts, though, who insisted on sitting on their stoops well into dark in the summertime, and cooking plantains and garlic with all the windows open.

Paul and Andrew got out of the car, promising me they’d be gone only ten minutes, twenty at most. They crossed Avenue D, pausing once to talk outside the entrance to the building. Undercovers do this thing where they learn to talk with their mouths barely moving, so that anyone watching can’t read their lips. I smiled observing my older brother, his arms crossed in front of his chest, dancing from one foot to the other to counter the bitter cold. His face, even at twenty-five, still had some of the round curves of his boyhood. I was four years younger than him but taller, with more sharp angles to my face—and to my personality. But he was still my protector against all threats, foreign and domestic.

I could tell from his impatient gestures what he was trying to say to his partner: let’s get this over with.

At that moment, Paul’s gaze locked onto mine. He was good-looking in a terrifying sort of way, with his jutting cheekbones and hatchet-like chin, wearing a snow-dusted sheepskin coat that would have set me back six months in tips at the restaurant where I worked, along with pale, acid-washed jeans. The corners of his lips curled upward, revealing the strong white teeth of a predator. A fleeting protective instinct made me want to call Andrew back to the car. To tell him to return with me to Brooklyn, leaving his partner to do whatever he was going to do. But Paul had already put a proprietary arm around Andrew’s shoulders and was guiding him toward the entrance.

They buzzed someone on the intercom and disappeared into the building.

I turned up the volume on the radio, pulled the heavy academy textbook onto my lap, switched on my penlight, and started reading: Corruption and Incident Complaints. In this course, students will examine the department’s complaint reporting system, the backbone of the COMPSTAT process…

I reviewed the proper techniques for filing complaints for bias-motivated incidents, threats to witnesses, police impersonation. When I looked at the clock, ten minutes had passed with no sign of Andrew or Paul. The woozy rain had turned to an icy sludge, the droplets on the windshield becoming hardened crystals. For the millionth time that month the radio station started playing “1999” by Prince, so I turned the dial until I caught a Britney Spears song, “Baby One More Time.”

My loneliness is killing me…I sang along with the track, my mind on Carla, my fellow cadet. Sweet, sweet Carla, who had “Frisk me” written all over her smile.

It was getting cold in the car. I maxed the heater, tilted the seat back, stared at the building across the street. On the second floor, in a brightly lit apartment closest to the corner, a little girl was standing at the window, the frame a tall, golden rectangle set into the exterior crusted with a century of grime. Her pajamas were yellow, the ebony hair springing in tightly coiled ringlets atop a dewy, round face. She was patting the window gently with both hands, her mouth open with laughter, fascinated by her breath ghosting on the glass. I waved to her, but I was too far away, and the interior of the car was too dark for her to see me.

A full twenty minutes had passed. In all of the information packed into the four hundred pages of the Police Academy textbook, there was nothing about the crushing boredom of the stakeout, the bane of undercovers everywhere.

The little girl in the window had turned her back to me. I could see that she was standing behind sheer curtains. Vague, dark shapes moved beyond the gauzy fabric. Adult-sized shadows were floating through the interior of the apartment, now fast, now slow, as though they were dancing. Someone was pushed toward the window, knocking the child against the glass, and I jerked up in my seat, fearful that the glass would break, cutting her—or, worse, pushing her out into the sky.

Within a moment, all the shapes beyond the curtains had disappeared from view. But the girl had pressed herself against one side of the window frame. She stood motionless, intently watching something inside the room. Her hands were cupped over her mouth in shock, or surprise. Yet it was the utter stillness of her rigid body that set alarm bells clanging in my head. I turned the radio down but heard only erratic traffic noises, buffered by the scrim of slush. I had been waiting in the car for nearly half an hour and my brother and his partner had not reappeared. A dark thought, like the onset of a migraine, tightened the muscles at my temples: Andrew and Paul were in that apartment.

Again someone was shoved up against the glass, face forward this time, the gauzy curtain revealing a man’s mouth opened in pain, or fear. The little girl crouched down, her arms crossed defensively over her head.

I wanted out of the car. But I was paralyzed with uncertainty. I could guess the CI’s apartment number and start ringing buzzers, but any distraction or interference on my part could jeopardize my brother and his partner. The interior of the car wasn’t cold anymore. It had become unbearably hot and close.

Then there was movement on the sidewalk below the window; Andrew and Paul hurrying across the street toward the car, my brother’s chin lowered into the folds of his coat. Paul’s face was a study in granite, expressionless. And it was the deadness, the lack of any animating emotion, that made me fling open the door, ready to propel myself from the car.

“Don’t get out,” Paul ordered, his voice low and urgent.

It was Andrew who got into the back seat this time. His partner threw himself into the passenger seat.

“Let’s go,” Paul said, eyes focused on the road ahead.

I checked the rearview mirror and saw Andrew with his head bowed, staring at his hands.

My eyes scanned the second-story window, but the child was no longer there.

“What happened?” I asked, my voice strangled with tension.

“I’ll tell you on the way back,” Paul snapped.

I hesitated and he turned his eyes to me and I understood that whatever had occurred in that apartment building was something bad. Something, I knew, that would not have happened without Paul’s presence.

“What’s going on?” I demanded, turning to Andrew.

“Drive!” Paul hissed, his face inches from mine. “You’re fucking up our entire operation.”

I put the car in drive and made a U-turn in front of the bodega, searching the apartment window one last time for a glimpse of the girl in the yellow pajamas. But she was gone, the filmy curtains flowing backward, as though pulled into the room by a strong vacuum.

We’d driven the few blocks to Houston Street, stopped at a red light, when the explosion ripped through the air behind us. I whipped my head around in time to see the street filled with fiery debris. The air was a dust cloud pocked with bricks and hunks of metal signage that rode the updrafts in untethered loops.

Paul’s hand wrapped itself like an electric wire around my wrist.

“Keep driving,” he said. “Or get out of the car.”

We heard the first sirens by the time we got to Delancey Street. A dirty gray plume of smoke rose behind us as we drove east over the bridge to Brooklyn. But we were almost to Franklin Street before Paul Krasnow opened his mouth again. His tone was steady, instructing. The CI had lured him and Andrew, and two other undercovers, to the apartment under false pretenses, he told me. What the CI had wanted was more money in exchange for information. When the cops refused, the CI had threatened to expose them all to the dealers they were setting up. One of the other two undercovers drew his weapon and told Paul and Andrew to leave, that they would deal with the CI.

“And the explosion?” I asked, my hands white-knuckled on the steering wheel.

Paul looked at me dead-eyed and said, “An unhappy accident.”

I pulled up in front of Paul’s apartment and waited for Andrew to corroborate or refute Paul’s story. When I finally summoned the nerve to check the mirror, Andrew’s chin was still buried in his chest. He hadn’t uttered a word.

“Look, the guy made drugs inside his apartment,” Paul said, his hand on the door handle, ready to bolt. “There were enough dangerous chemicals to blow up Chelsea Pier. It was bound to happen sometime.”

Before he had finished speaking, I knew the entire story had been pulled out of thin air in the short time it took us to cross the East River. And that he was feeding it to us both.

Paul thrust the door open and got out. But before he shut the door, he said to me, “You say anything about what happened tonight and we’re history. And that includes your brother. You got it?”

He waited until I nodded, then said to Andrew, “We good?”

When my brother didn’t respond, Paul leaned in over the front seat and asked again, “We good, partner?”

Andrew looked at him and nodded once.

I drove to Greenpoint with Andrew in the back seat, his body hunched, voiceless, a portrait of misery. I parked on the street in front of our parents’ house, the house where we both still lived, the engine running, the heater insufficient for the cold. I wanted answers. When had the other two undercovers shown up? Was any part of Paul’s story true? But more terrible than not knowing was the possibility of knowing what my brother had done.

I studied him in the mirror, his image as familiar as my own, taking in the new coat, the expensive watch, remembering his girlfriend’s new necklace, and it gave me all the answers I needed.

“There was a child in the apartment,” I told him, my voice barely above a whisper.

He did not exit the car so much as launch himself from the back seat, and he stumbled up the steps and into the house. I followed close behind, my fear giving way to anger. I banged through the front door in time to see Andrew running up the stairs, taking the risers two at a time. In front of the stairs, my father stood sentinel. As though he had been waiting for us all evening.

“Leave him alone,” he barked at me, blocking my way, his eyes bloodshot from Jameson.

I tried to push past him but he shifted deftly like the street fighter he had been, his mouth a thin line of disapproval.

“You don’t get to ask what happened,” he said, his sour breath in my face. “You’re not a cop. Yet. You haven’t earned the right to ask the hard questions.”

When he was satisfied I wasn’t going to follow Andrew up to his room, he shuffled unsteadily back to his recliner, focusing his eyes again on the television screen.

“Until you’ve walked the walk,” he said, drinking from his glass gripped with careless fingers, his face indistinct in the shadows, “you can’t possibly know what it means to keep a fellow officer’s confidence. When, and if—and that’s a big if—you earn your badge, you’ll find out there is no ‘thin blue line.’ There is no black or white. There’s only a wide gray band the size of Brooklyn that separates us from the perps, and the rest of the clueless civilians.”

I remained in the darkened room with him and watched the news reports already coming in about the explosion in Alphabet City. A four-alarm fire had burned the entire building on Avenue D and would have destroyed neighboring structures if it had not been a stand-alone, and if all the rooftops hadn’t been so wet. Most of the apartments had been evacuated, but the tenants on the second floor were incinerated.

In the morning, the remains of three adults and one child were recovered, their flesh gone, their bones charred to ash. The explosion had burned hot and fast, helped along by an accelerant. The destroyed apartment had been owned not by some desperate junkie who might have been working as my brother’s CI but by a high-level drug dealer named Raphael Trujillo-Sevilla. By the afternoon, it was confirmed that two policemen were among the adults who had perished in the blaze.

There was a formal, citywide investigation after the incident. Rumors of police corruption swirled—officers taking bribes from dealers to look the other way, planting evidence on the players who wouldn’t pay up, even orchestrating hits on snitches who threatened to turn state’s evidence—but nothing ever came of them. Not one officer was even cautioned, and the streets went back to business as usual. The lone assistant DA who tried to make a name for himself by pressing for further investigation left in disgrace after photos of his tryst with a prostitute were leaked to a prominent city paper.

Of course, there had been witnesses on the street that evening who gave testimony about the circumstances surrounding the explosion. At one point during the inquests, a report surfaced that a red Toyota Corolla, the same make and model as mine, had been spotted leaving the front of the building moments before the explosion. But it was a commonly seen car in Manhattan, and the report went nowhere.

One evening late, two NYPD officers came to our Greenpoint home and disappeared into my father’s office—a private, smoke-filled place I’d rarely been allowed to view, let alone visit. After an hour, my father called me into the office and closed the door. The good bottle of aged whiskey was perched on the desk, its contents well diminished. The officer with the lieutenant’s badge smiled at me—a thin-lipped, humorless grin—and told me I had nothing to worry about. My impotent rage threatened to erupt from my head like a geyser of blood onto the tobacco-stained walls of the study. I almost told them, the unspoken words like a knotted rope through my tongue, that it had been me who had sent the anonymous note about the Toyota to the ADA’s office.

I’d stopped talking to my brother altogether, spending most of my time away from the house, catching only brief glimpses of him as he tried to make his way silently through the hallways, or when I passed him in the kitchen, my body shrinking from any contact with his.

The last time I heard Andrew’s voice was when he spoke to me through my closed bedroom door.

“Betty,” he had called, rapping softly with his knuckles. “Please…”

I got up only to lock the door and turn up my radio.

Two weeks after the explosion, my brother killed himself. His shirtless body was found on a frigid south Jersey shoreline in early February, with no outward marks of violence to indicate how a strong, seemingly healthy young man could have ended up washed from the Atlantic Ocean, until an autopsy revealed a fatal amount of barbiturates and alcohol in his bloodstream. The coroner’s report also noted that he’d had red hair and blue eyes. Almost identical to mine.

I had never asked him the hard questions. I had never asked him anything at all. But in a letter left to me, Andrew told me about the fire. He and Paul Krasnow had been taking protection money from Trujillo-Sevilla. The dealer had tired of paying so much and threatened to expose them. The two undercovers who were killed were also bent, but they were willing to be less greedy. Tempers had flared, guns were drawn, and Andrew shot one of the cops. Paul followed by shooting the second cop and the dealer. From there it had been an easy fix to rig the gas stove to blow: the gas turned on at every burner, a lit candle, drug-making chemicals upended, and a fast retreat. Andrew had no idea a child had been in the apartment. It was this last bit of knowledge that pushed him over the edge. He just couldn’t live with the guilt.

I tore up the letter and never revealed to another soul my brother’s part in the whole dirty mess.

A year later Paul Krasnow made sergeant. It was his hand that I shook onstage at my cadet-graduation ceremony, welcoming me into the brotherhood of silence, the smile on his wolfish face taunting and smug. Once I became active duty, I followed his every move, right up until the day he was taken out by a bullet to the back of the head by a retaliating cartel enforcer. Or maybe another cop settling a score.

I burned Paul’s newspaper obituary while it was still in my father’s hands. He’d been reading the paper over his usual breakfast of bitter regret and Jameson, and I’d simply reached forward, lighter in hand, igniting one corner with a pass of the flame. When he dropped the paper, his astonished eyes met mine, and for the first time realized he was looking into the eyes of an honest cop.

Chapter 2

Monday, December 30, 2013

Dallas, Texas

This I’ve come to know. Avoiding uncomfortable truths about oneself is like putting a threadbare mattress over hard, stony ground. No matter which way you turn, it’s going to hurt. Might as well quit stalling and get busy clearing the field.

Yet here I am in a ramshackle dive, facedown on a hard bench, submitting myself to a man holding an implement of torture—in this case, a tattooing gun.

The awkward position causes my right leg to cramp, the leg with the ruptured Achilles tendon, the shredded fibers sewn together with medical sutures strong enough to hold up a suspension bridge. The calf muscle twitches more painfully, and I flex the toes carefully upward to forestall a massive spasm.

It’s been a full three months since the reparative surgery, and an agonizingly slow recovery and rehab. Three months and change since a narrow, plastic-coated cable was threaded through an incision in my ankle, forced beneath the major tendon, and passed through to the opposite side. The ends of the cable had been fastened together and attached to a heavy chain, the far end of which was anchored to a large stone upon which my captors had painted SUBMIT, E 5:21.

The E for Ephesians, the number indicating the biblical chapter and verse: “Submit yourselves one to another in the fear of God.”

Closing my eyes, I can still hear Evangeline, my captor’s voice reciting the passage in her gliding East Texas accent. It was during a long, hard drug investigation that I’d been held prisoner by Evangeline Roy and her two sons, the leaders of a cultlike ring of meth dealers. Several people had died, including a member of my own team, and I’d managed to survive, but just barely. The injury to my leg had curtailed, maybe forever, my ability to run—the key to my sanity. Until my injury I had run faithfully every day of my life, through other hurts, fevers, sprains, burns. I ran to keep the internal destructive forces at bay; the Kali-headed, bile-throated, hatchet-tongued impulses that threatened hourly to overcome every peaceful, balanced, orderly event in my life.

The best thing in my world was my partner, Jackie, the love of my life. But the past three months of sick leave from the Dallas Police Department—limping around our new house looking for something constructive to do, too wired to sleep at night, too mentally exhausted during the day to be truly useful—had come close to bringing my relationship with Jackie to an end. My irritability, the volatile frustration that I couldn’t quite keep a lid on, had strained her monumental patience to wilted apathy.

I hear a restless shifting and crane my head over my shoulder to look at the guy standing behind me. He’s shirtless, his shaved head glowing dully under the overhead fluorescent lights, bulging pectoral muscles inked with a large skull entwined with snakes, twitching impatiently. I’ve been told he’s a master at what he’s about to do.

“I haven’t got all day,” he warns me, grabbing hold of one of my ankles.

“Yeah,” I say. “Just give me one more minute. Please.”

I’m pathetic, cowardly.

You and no one else brought yourself to this, I think.

The worst part of not being able to run, though, has been the loss of connection to my uncle Benny—my father’s brother, and a respected homicide cop with the 94th Precinct in Brooklyn—the total and absolute evaporation of his voice, his wisdom, his warnings and admonitions from my head. When I run, I hear him as clearly as though he was racing alongside me, breathing into my ear. The fact that he’s been dead for several years has not vanquished my certainty that he’s out there waiting to talk to me, if only I could unleash my mind to channel him.

Betty, he’d probably tell me in this moment, you’re being an asshole. You’ve been diminishing the finest thing in your life. You’re driving Jackie away, and then you’ll be stuck forever in the abyss of your own morass…

“Hey,” the guy barks.

“Okay,” I breathe. “I’m ready, you bastard. Do what you have to do.”

A metallic, buzzing noise starts up. Holding the now-active tattooing gun, the guy takes a seat next to the bench where I’m lying and begins the long, tedious process of inking in the outlines of the design that he’s drawn on my right calf, just above the damaged ankle. The guy, professional name Tiny, was recommended to me by my partner, Seth, who swore to me that he’s an artist, the best tattooist in North Texas.

I grab at the Saint Michael medallion hanging from a chain around my neck. Gone is the original medallion, which had been a gift from my mother, making me the third generation to have worn the old emblem, pitted with wear, brought from Poland. It had been taken by Evangeline while I was rendered unconscious, and I had no real hope of regaining it.

Jackie, always thoughtful, had replaced the missing medallion with a new one. It was beautiful in the way that modern copies often are—shiny, a little too hard-edged, a little too perfect—but I wore it every day, even as I mourned the loss of the original.

The tattoo on my leg is slowly taking the shape of the Archangel Michael, the patron saint of cops, wielding a sword, about to skewer a dragon beneath one sandaled foot. The tattoo will be large and lurid.

But the pain is immense, the prickling, punching needle ravaging the already hypersensitive skin around my surgical scar, which will be fashioned into the body of the serpent-devil. It will take hours to complete. Against Tiny’s recommendation, I’m doing it all in one sitting. He’d warned me I would rather be shot in the stomach than continue the process past the first thirty minutes. Tiny’s been shot seve. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...