- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

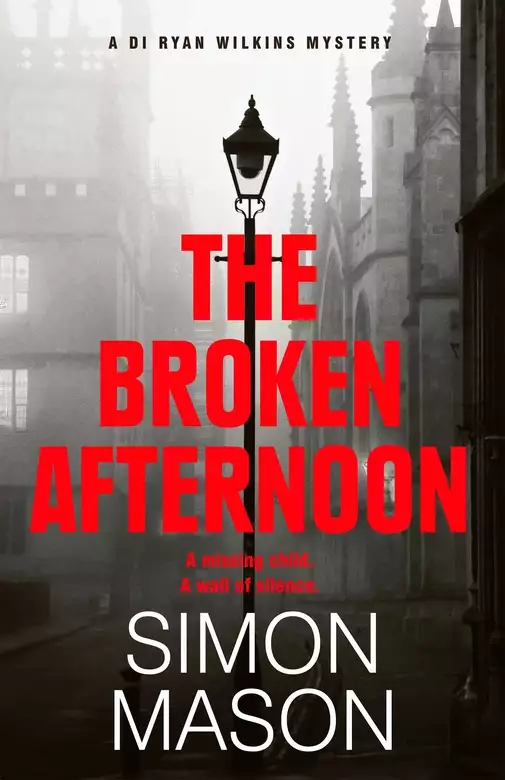

A DI RYAN WILKINS MYSTERY

A SHOCKING DISAPPEARANCE

A four-year-old girl goes missing in plain sight outside her nursery in Oxford, a middle-class, affluent area,

her mother only a stones-throw away.

A TRIGGERING RESPONSE

Ryan Wilkins, one of the youngest ever Detective Inspectors in the Thames Valley force, dishonourably discharged three months ago, watches his former partner DI Ray Wilkins deliver a press conference, confirming a lead.

A DARK WEB

Ray begins to delve deeper, unearthing an underground network of criminal forces in the local area. But while Ray's investigation stalls Ryan brings his unique talents to unofficial and quite illegal inquiries which will bring him into a confrontation with the very officials who have thrown him out of the force.

Praise for the DI Ryan Wilkins Mysteries

'Mason has reformulated Inspector Morse for the 2020s' The Times

'Start now and avoid the rush' Guardian

Release date: February 2, 2023

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Broken Afternoon

Simon Mason

Ten hours later, five miles away, in a poky shed-like office smelling of engine oil and instant coffee, night-watch security guard Ryan Wilkins broke the long hours of his shift by catching the news on repeat. Two o’clock in the morning, night rain creeping with tiny claws across the plastic roof. He turned up the volume and leaned in.

On the screen: his former partner, Detective Inspector Raymond Wilkins, flanked on one side by the new Superintendent and on the other by the Thames Valley Police crest in gilded carpentry, fronting a presser. A little girl gone missing. Her picture appeared, an irresistible advert for the human race with her blonde curls and dimples, her bunched cheeks and shining eyes, appropriately pleased with herself in pirate costume, eye-patch and cutlass, ribbons and sash. Vanished from outside her Oxford nursery while her mother talked for no more than two minutes to her teacher in the lobby. A picture of the nursery appeared too, a snippet of sculpted beech hedge and immaculate lawn – another advert, for parental serenity, priceless at fifteen grand a year. From which, in broad daylight, a little girl had been snatched. Upper-middle-class England was freaking out. In the echoey conference room journalists shouted questions over each other.

DI Wilkins said they were following a lead but declined to give details, and Ryan turned him off and sat there in the sudden quiet staring out of the window at the rain-crackly darkness of the van compound beyond. He could imagine the situation. A news shout so quick wasn’t ideal – things were still too messy – but the timetable of sensational cases was driven by the media. A lead? If real, probably the father; Ray pointedly hadn’t mentioned him and the disappearance of very young children was mostly the result of parental disputes. Ray would be good at dealing with that, smooth and tactful. He’d looked good on television too, no denying it. Cameras loved him, tall and black in his uniform; they loved his serious features, educated tone, the way he paused between sentences, the firm shapes he made with his strong hands, the resolute look in his eyes. Handsome Ray. The thinking woman’s law enforcement.

Ryan considered his own reflection in the window. Skinny white kid in nylon uniform, a discount purchase from myworkwear.com. He looked at his overlarge nose and attention-seeking Adam’s apple, quick eyes under scratchy brows, shiny smear of scar tissue down his left cheek, a grimace about to happen, a fidget coming on somewhere – Ryan Earl Wilkins, twenty-seven years old, trailer-park rat boy, one of the youngest ever detective inspectors in the Thames Valley force, dishonourably discharged three months ago, now working nights at Van Central, off the Botley Road. Boom. Hero to zero in three minutes. Or two and a half.

Still, Ryan was never down for long; he always revived, without warning or indeed reason, his optimism an inexplicable part of him, unasked for, like his nose, his fidgets or his beloved son, Ryan Junior, nearly three years old, by far the calmest and most discerning of all the Wilkinses, asleep now at home with his Auntie Jade. Grinning at the thought of him, Ryan was turning on his broken-backed swivel chair to put the kettle on when his eye was caught by a tiny blip in the corner of the security screen. Gone almost before it had happened, but not too quick for Ryan. Things stuck to his eyes. Another quirk.

He stared unblinking at the screen for two minutes more. Nothing. Only the unvarying van compound, an area of grizzling darkness, of rental vans stored between railings, a big box of toys put away at bedtime, a dead zone of silence, complete stillness. Except, just momentarily, a brief tremor in the texture of the shadow of a Ford Transit. A little jolt of interest went through him. He initiated the required security procedure, activating the police response and logging the time, checking the codes for the doors to the offices and workshop. All fine. Everything was nice and smooth – until he tried to switch on the compound floodlights. Not a glimmer. After a moment he began to rummage in a drawer of his broken-down desk for a flashlight.

Outside, silvery rain was drifting down on a fine breeze scented with diesel, and Ryan followed the beam of his torch across the concrete forecourt to the metal gates, still securely padlocked. As he went, he mentally reviewed the last few hours for signs of anything out of the ordinary he might have missed. There was nothing he could think of. When he’d arrived at ten there had been a van left on the forecourt – usually there was at least one – and he’d driven it inside the compound and parked it and locked it, as per, and given the pen a last look round. Everything had been secure; he’d double-checked the gates. He looked about him now. The compound was surrounded by a two-and-a-half-metre-high palisade fence in galvanised steel, pretty much burglar-proof. Perhaps an animal had got in, one of those muntjac deer from the water meadows at Hogacre. He’d seen them on the pavements among the surrounding warehouses, strange creatures, dog-like, with foreshortened front legs and raised hindquarters, creeping along as if in shame. He scanned the ground ahead as he unlocked the gates and went inside, listening. The vans around him seemed to bulge forward in the torch beam as he waved it slowly to and fro, walking down the narrow channels between them. He came to a halt at the end of a line and waited a few beats, listening again. Nothing but the whisper of rain on van roofs. And then, five metres away, very softly, a scrunch of gravel.

He switched off the light and went quietly back along the row towards the entrance, and a shadow movement on the other side of the line of vans seemed to keep pace with him. At the end he waited a moment, then stepped smartly to the other side.

The figure looming in front of him was big, six six at least, and bulky, head hooded. When Ryan appeared, he flung his arms out and canted forward with a grunt, but Ryan was quicker, shining a light at him with one hand, taking a picture with the other before he could flinch away.

There was a panting pause as they confronted each other, a moment of unexploded-bomb uncertainty when things could still go either way.

Ryan said, ‘Go ahead, kill me with a spanner, why don’t you? Murder first degree, ten to fifteen in Grendon, no parole, come out in time to waste the rest of your fucking life on street meds.’

More panting.

He tensed himself.

Then the figure spoke, a deep sticky voice. ‘Done Grendon already.’

Ryan hesitated; a flutter of recognition went through him. ‘Mick Dick?’

The man lowered his hood and showed him his face, trembling. Those familiar puffy cheeks, those bloodshot eyes, lopsided mouth. All distorted now in fear. Terror.

‘Mick Dick! What you doing here?’

All the man could do was moan. Passing a big hand across his face, he brought it away shaking. Shook his head, dumbly suffering. He didn’t seem able to speak. Something was wrong with him. Ryan stood there shocked, puzzled, trying to remember when he’d seen Mick Dick last: maybe not since school, when they were both sixteen, when Mick was still promising, a boxing heavyweight in the Nationals, trying out for Wantage Town, and Ryan was running wild at the raves and in the clubs.

‘What the fuck’s the matter with you?’

Still no reply. Moans. Some trembling.

‘Jesus Christ, Mick Dick. Didn’t even know you were out.’

He’d read about it at the time. Aggravated burglary, minimum five at Grendon, category B facility out in Bucks. Nice lad, Michael Dick, but easily led, always doing favours for the wrong people. Some weakness let the violence in. They said the man he’d attacked during the burglary was in a coma for a fortnight.

Looking at Ryan with his bloodshot eyes, he finally spoke. ‘Two months. Trying to get work. Every day, man, knocking on doors.’ He moved his tongue around his lips. ‘Get something soon. But this. This is fucked up. I can’t be here.’

‘Yeah, well, don’t want to let you down too badly, but you are actually here, and you need to tell me what the fuck you’re doing.’

‘I’m telling you, Ryan, it’s a mistake.’

He was shaking again.

‘Listen. You got about five minutes before the bobbleheads get here. You can explain to them if you like.’

There was a faint noise wafted on the breeze: sirens.

Mick Dick was moving his head wildly; he said in a rush, ‘Ryan, Ryan, man, can’t go back. They put me away for long this time. Got a little girl, four years old, she grow up without me. Ryan!’

‘Calm down. I need to know what you’re doing here. Say something I can understand.’

‘I got nothing, I done nothing, I swear.’ He spread his arms. ‘Check me out, man. It’s just . . .’

‘Just what?’

He looked ashamed. ‘I got nowhere to stay. She kick me out till I get my shit together.’ He gestured hopelessly at the sky. ‘It’s raining, man.’ In his voice nothing but defeat. An ex-con on the street.

‘You been sleeping in vans?’

He said in a sullen whisper, ‘I done it, other places. There’s always one left unlocked. But not here, man, you locked up tight.’ He gave Ryan a closer look. ‘What you doing here anyway? Thought you went for a police.’

‘Never mind that. Show me again.’

He put his light on him and Mick Dick turned out his trouser pockets, stood there humble and defenceless as if convicted already. Nothing but his wallet, bunch of keys, papery scraps of rubbish scattering on the ground.

‘That’s it, that’s everything. All I got.’

The sirens were closer now.

‘Ryan, man. Got to help me out.’ His mouth was loose with fear. Terror, again. ‘My little girl, Ashleigh,’ he said. Plucking at his lips with his teeth.

Ryan looked at him.

‘You know,’ Mick Dick said softly. ‘I can see it.’

‘Know what?’

‘Know what it’s like. Be out of luck.’

Ryan thought of Mick Dick aged sixteen, taking his boxing seriously, doing what he was told, forgetting to think for himself; he thought of handsome Ray on the screen, of himself in the fuggy shed where he spent his nights. There was no sound of the siren now, only the long, rising engine-whine of acceleration coming along the stretch of Ferry Hinksey Road two hundred metres away.

He had thirty seconds to decide. Do the right thing, do the wrong thing.

‘Go on then. Fuck off. Don’t come back till your luck’s changed.’

Mick had already gone. Moved easily for a big lad. Of course, he was practised: slipping in and out of places is what he’d gone down for.

The squad car was on the forecourt and Ryan ambled out to meet them. Two bobbleheads known to him only by sight.

‘Good news, boys,’ he said. ‘No need for heroics. Turns out just one of those little deer things got in. Thanks for your time and that. Always nice to have a spin, eh?’

And he watched them drive away.

THREE

At the bottom of the hill below Christchurch College and the cathedral – those grandiose monuments of piety and swag, gorgeously dressed in morning sunshine – St Aldates police station sits drably on the main road, an architectural poor relation, a low-slung building of pale stone, like a wash-house with pretensions. Nearly a hundred years old and considered unfit for purpose for about fifty. The main Thames Valley police work is done elsewhere now, at Cowley and Kidlington, but in the listed building a reduced staff pant on, making do in cramped offices and corner-spaces among inconvenient new air vents and electrical infrastructure. The downstairs has been much knocked about. Behind the public front desk is a tedious maze of walkways between meeting and interview rooms, and, on the floor above, misshapen offices and briefing rooms bodged together over the years. Only on the top floor, around the new open-plan, have some original rooms been preserved, with their period window-seats, fireplaces and stuccoed ceilings, now the desirable offices of the senior ranks, including, at the south-eastern corner, Superintendent Dave Wallace, hard bastard of the old school with grey buzz cut and inflexible jaw, one month into the job and flinty keen to make his mark.

Seven thirty in the morning, a fine day after overnight rain. Geese on the river throwing out strangulated cries. Smells of coffee, medium roast, Blue Mountain Jamaican.

On Wallace’s desk was a copy of a police dossier titled Diversity, Equality and Inclusion Strategy, a recent directive mandating new recruitment policies and incidentally providing new criteria by which superintendent-level attainment would be judged. Something had caught Wallace’s eye: targets for representation in the detective inspector class of white boys from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Currently, this was the hardest group to reach and, given the usual requirement of a degree and a highly selective training procedure, new recruits from the group were the slowest to arrive. From scratch, it took five to seven years. Consequently, the recognition awarded to superintendents for success was proportionately greater. Quick wins were big wins. And that was why he was reading another report titled Misconduct Procedure: Thames Valley Police vs DI Ryan Wilkins. If new recruitment could take seven years, reinstatement could be done in a few weeks. Wallace was nothing if not shrewd. And he’d come up himself from hard times. But first he needed to know how reformable the dishonourably discharged Wilkins was.

He sipped coffee as he read.

Ryan Earl Wilkins, born 5 February 1990, Hinksey Point Trailer Park, Oxford, England. Educated at New Hinksey Primary and Oxford Spires Academy. No formal academic qualifications. Accepted onto the Inspector Level Direct Entry Programme June 2013. Fast-tracked to completion December 2014. Top attainment marks in his group.

Wallace frowned, stopped reading. Acceptance onto the Direct Entry Programme was unusual, particularly without prior qualifications. To complete the course in eighteen months was borderline irregular. He knew of only one other person who had done it. Himself.

He read on.

First career posting: Wiltshire Police, terminated in dismissal after six months for Misconduct. Allegations brought by the Bishop of Salisbury of breaching the following Standards of Professional Behaviour: a) Honesty and Integrity, b) Authority, Respect and Courtesy, c) Discreditable Conduct. Proven. Verdict overturned on appeal.

Second posting: Thames Valley Police, terminated in dismissal after four weeks for Gross Misconduct. Allegations brought by the provost of Barnabas Hall, Oxford, and others, of breaching the following Standards of Professional Behaviour: a) Authority, Respect and Courtesy, b) Discreditable Conduct, c) Equality and Diversity. Proven.

A disaster, a fucking pile-up. Looking grim, he flipped a page.

Family. Ryan Wilkins has one son, Ryan Wilkins Junior, aged two years and nine months at the time of writing. The child’s mother, Michelle Toomey, is deceased. The father of Ryan Wilkins, Ryan Wilkins Senior, is currently serving a custodial sentence at Huntercombe Prison, Henley, for the abduction and threat to cause bodily harm to Ryan Wilkins Junior.

Christ almighty. Family fucking saga from hell. Closing the folder, he looked out of the window, along the river where the geese were asserting their pain, past park-like Christchurch Meadow with its ruminating deer, past the university boat houses and booming ring road, towards Hinksey Point Trailer Park crouching out of sight in its hollow of traffic noise and dirt. He was a man of short bursts of forceful thinking and sudden decisions. He liked to do things his own way. His fingers ticked on the desk as he frowned. Then he brusquely pushed the folders to one side and consulted his watch, already impatient for the imminent arrival of the senior investigating officer of the missing girl case, due to deliver his morning report.

Leaning forward above the washbasins in the lavatory on the first floor, DI Raymond Wilkins gave himself a last long, narrow look. He’d been awake since five o’clock when Diane, his wife, had come into the spare room in distress asking for hot flannels and oat milk. Before she became pregnant, he’d never heard of oat milk; now they bought it in bulk and the fridge was stacked with cartons of it next to the multi-packs of pickled gherkins, ice cream and Polish dumplings. He’d never seen Diane sick before either but over the past few months she’d been ill literally most of the time, with persistently high blood pressure, second-trimester gestational diabetes and periods of hyperemesis gravidarum, vomiting so continual that at one point she’d been forced to spend three days in hospital on a nutrient drip. She’d changed in other ways too. Her shape, obviously. Not big to start with, elfin in fact, carrying twins she was all bump, a child clutching a medicine ball, staggering round the house, anxiously looking for somewhere to put it down. She had a look, hunted and furtive, seen by him before only in the eyes of certain first-time offenders, those without anyone to help them, frightened enough by the thought of prison to do something desperate. It was clear that she blamed him for her condition. He had started to feel a little afraid of her.

‘I’m here for you,’ he told her, over and over. ‘Here I am.’ But she pushed him away. The truth was, he was good only for hot flannels and oat milk. He was on the outside, at fault. She was irritable and cross. For five weeks straight he’d been sleeping in the spare room.

He peered hard in the mirror. He was blurred around the edges, eyes gritty, skin loosening around the mouth. The glory days of Handsome Ray, when he only had to look at a woman a certain way to see a spark of interest come into her eyes, were gone. He missed them. But a phrase of his father’s came to him: the sun that melts the wax hardens the clay. He summoned the will to make it good, to be less desirable but dependable, sleepless but unflagging, pushed away but unbudgeable. To be the man his Nigerian father had always wanted him to be in Britain, as, in fact, he had become, Detective Inspector Raymond Wilkins, Balliol College graduate, boxing Blue, currently SIO on one of the country’s highest-profile cases.

His phone rang and he glanced at it, frowning. Diane. He looked at his watch, hesitated a moment, then cancelled it.

Straightening up in front of the mirror, he turned to the left, to the right, examining himself. He adjusted his Mr P suede trucker jacket, brushed a speck of lint off his Acne Studios dark navy denim jeans. Put his Ray-Bans back on. Even a wreck can dress well. Then he turned and went out, and walked across the open-plan to the Superintendent’s office.

The Super didn’t like Ray, didn’t like his educated tone, his middle-class manners. Ray didn’t like the Super either with his hard-man tics and Govan accent. He had a habit of looking at Ray without blinking and asking abrupt questions.

‘News on the father?’

‘Not yet, sir.’

Poppy’s father, Sebastian Clarke, thirty-eight years old, a clever, ambitious man known in north Oxford dining circles for his impatient views of public healthcare, was a senior consultant at the Radcliffe Hospital. He’d separated acrimoniously from Poppy’s mother, Rachel, a year earlier, since when they had been in a bitter dispute over custody of their four-year-old daughter. According to Rachel, he’d twice threatened to take Poppy to France, where he had a house. Only a week earlier Rachel had been granted a court order against him until the childcare dispute was resolved. He’d not been seen at the hospital since the morning before and was not replying to calls or messages.

‘Place him outside the nursery?’

A car matching the description of Dr Clarke’s silver Mercedes had been seen by a witness in Charlbury Road, but they hadn’t yet found it in the CCTV: there were no public cameras in the side streets near the nursery; they were waiting for access to the private cameras outside The Dragon and Wychwood schools on Bardwell Road. One of Ray’s team, Nadim Khan from Communications and Intelligence, was on it.

‘Don’t let it take too long.’

‘No, sir.’

‘Where does he live?’

Since leaving the family home, Dr Clarke had been living in one of the canalside apartments in Jericho. It had been placed under surveillance but there had been no sighting of him there.

‘Warrant?’

‘We’ll get it later this morning.’

‘Shouldn’t be waiting for these things, Ray.’

‘No, sir.’

Geese yelps came through the window while the Super did his staring thing.

‘Witnesses? Eyes on the little girl?’

No one had seen anything. Garford Road was a cul-de-sac, a backwater. The roads around it – Charlbury, Bardwell, Linton, Belbroughton, those impeccably mannered avenues of lilac bush and mellowed brick – had been almost deserted, the only people in them a handful of workmen, a dog-walker or two and a few schoolchildren drifting home from after-school clubs. Ray’s DS, Livvy Holmes, was tracking them down and taking statements but no one so far had seen or heard anything out of the ordinary. The construction workers had all been interviewed and their vehicles were going through forensic analysis.

‘SOR?’

They exchanged a brief, tight look. Neither wanted things to develop in that direction – Operation Silk, the investigation into historic child sexual exploitation in Oxford, was still traumatically vivid in the memories of many at the station – but Ray’s team had run a review of the sex offenders’ register and pulled out names of men to be interviewed.

‘Gut?’

‘Feels different.’

‘Why?’

He paused. ‘She’s so young.’

‘Some bastards don’t know the meaning of too young.’

Ray acknowledged it. ‘Still, it’s such a quiet, exclusive sort of place, any stranger hanging round is bound to be noticed. And if Poppy had been snatched, there would have been some sort of commotion, someone would have heard something.’

‘So you think the father took her?’

Their eyes met again. No blinks from the Super, only a cold, hard examination of Ray, a laser point of purpose, while the geese on the river screamed.

‘I hope so,’ Ray said at last.

Abruptly Wallace fired off more questions. ‘Talking to the Hub? What about CRA? Next steps?’

The Hub was the local intelligence-gathering centre and Ray had been in touch with Maisie Ndiaye there; he was expecting a preliminary view from her later in the day. The Super looked sour: he wasn’t a fan of the so-called profilers. The Child Rescue Alert was a system for putting out appeals to the community. The feed had been up and running since the night before with photos and bulletins, and the Twitter response had been unbelievable; the in. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...