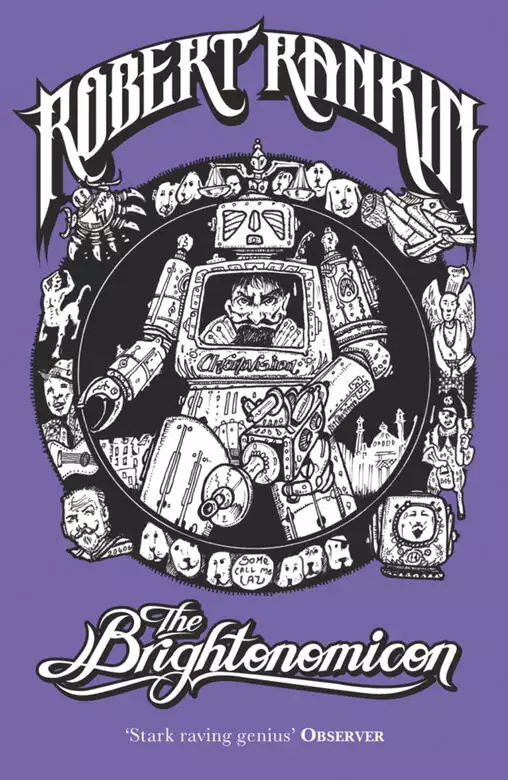

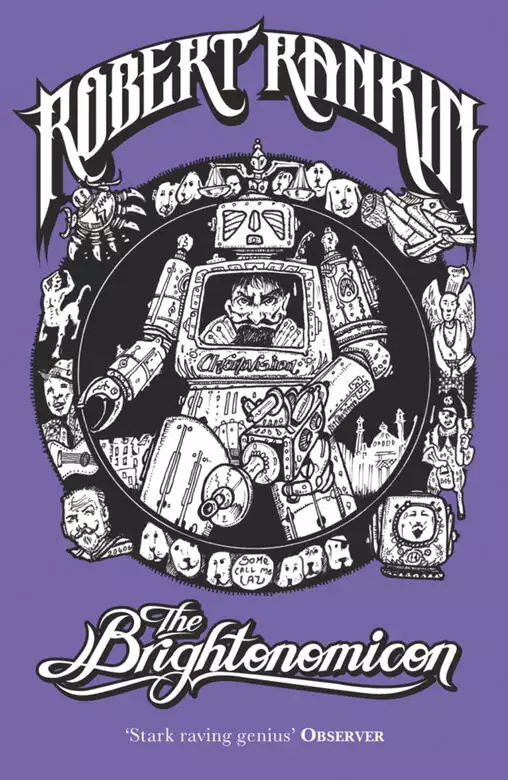

The Brightonomicon

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

“An amazing audio adventure…David Warner is a terrific Rune…the thing’s so flipping entertaining, you’d be perfectly happy to sit through another six-and-a-half hours. 5/5” – SFX

This is the tale of two incredible people – one who knows he is incredible and the other who learns to be incredible. Set in 1960 in the UK south-coast resort of Brighton, self-styled guru and magus Hugo Rune rescues a young man from drowning and persuades him to become his assistant and partner in solving 12 mysteries. Rizla (for such is the young man’s assumed name) agrees to help as he has lost his memory and has nowhere else to go. There then follows 12 of the most baffling, surreal, exciting, head-scratching and downright far-fetched mysteries ever written…all based in and around the suburbs of Brighton.

In between the adventures our heroes are able to enjoy the bizarre surroundings of Fangio’s pub, where the bar lord is always happy to talk some old toot and occasionally some exposition as well. Across the mysteries Rizla and the audience learn about the Brighton zodiac, the chronovision, time travel, centaurs, a dastardly plot where the NHS kidnap vagrants for body parts, space pirates, the real history of Victorian Britain, Brighton pirates and the fate that awaits mankind should Hugo Rune fail in his task. And of course, there’s a very bad man involved indeed – Hugo Rune’s arch-nemesis of the ages, Count Otto Black – who wants to rule the world (what else!) You will never hear anything else quite like this in your lifetime.

13 x 30’ Episodes

Full Cast Drama/Comedy Adapted from Robert Rankin's original novel

Release date: June 16, 2011

Publisher: Spokenworld Audio & Ladbroke Audio Ltd

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Brightonomicon

Robert Rankin

And I was dead.

I confess that I found this circumstance somewhat dispiriting, for I had always been of the opinion that a long and prosperous

life lay ahead of me. To be so suddenly deprived of existence, and at such an early age, seemed grossly unfair and I determined

to take the matter up with God at the first possible opportunity and register my extreme disapproval.

The opportunity, however, did not arise and I did not have words with the Divinity. Perhaps He had business elsewhere, or perhaps, in His infinite wisdom, He had already mapped

out my future and was simply sitting back upon His Throne of Glory, observing the situation.

Or perhaps, just perhaps, He does not exist at all.

My death occurred on Saint Valentine’s Day in the Sussex town of Brighton. Or more precisely two hundred yards off the coastline,

in the chilly waters of the English Channel. I had travelled down from my native Brentford by train with my teenage sweetheart

Enid Earles, hoping for a weekend of sexual adventure in a town that is noted for that sort of thing. I had even purchased,

from Mr Ratter’s jewellery shop in Brentford High Street, an engagement ring set with faceted glass that might well have passed

for a diamond in uncertain light, my hope being to offer this to my love should she display any signs of hesitancy when it

came to the moment of actually ‘doing it’. Sadly, as it turned out, this ring was given up to the waves and my relationship

with Enid never went beyond the platonic. Which is not to say that she did not indulge in the carnal pleasures upon that fateful

weekend. Simply that she did not indulge in them with me.

We had taken, as I now recall so well, a stroll upon the Palace Pier, where I made some attempts to interest Enid in its architectural

eccentricities. She yawned somewhat and I, in my innocence, took this to be a sign that she was eager for bed. I suggested

that we take a drink or two in the pier-end bar before turning in (I confess to a degree of Dutch courage being required upon

my part, for I was young and, though eager, inexperienced). Enid agreed and I ordered a Babycham for her and a large vodka

for myself. And, as an afterthought, asked the barman to add a large vodka to Enid’s Babycham also.

We were three or four drinks in when the unpleasantness occurred. This day before yesterday being in the nineteen sixties,

Brighton was playing unwilling host to a large contingent of Moderns, or Mods as they were then called, and a goodly number

of these young hobbledehoys were milling around in The Pier Bar. They wore gang-affiliated patches that announced them to

be members of the Canvey Island Mod Squad. And one of their number – their leader, I presumed, by the nature of his arrogant

bearing and loquaciousness – took an unhealthy shine to my Enid.

I have never been a man of violence and although I have always been sure that I would be able to ‘handle myself’ in a sticky

situation, I was vastly outnumbered, and possessing not the martial skills of the legendary Count Dante, creator of the deadly

art of Dimac, I suggested to Enid that we should take our leave, head for our rented room and get to know each other better.

Enid, however, did not seem too keen. In fact, she performed shameless battings of the eyelids towards the leader of the gang,

who approached our table and made suggestions to Enid that were little less than lewd. I took exception to this and made certain

suggestions of my own, mostly to the effect that this interloper should take himself elsewhere at once.

More than words were then exchanged, which resulted in myself being hauled bodily out of the bar by several burly Mods and

thrown from the pier into the frigid waters beneath.

It is well recorded that in those final, fleeting moments that precede the onrush of sudden death, one’s life is said to flash

before one’s eyes, much in the manner of a movie of the biopic persuasion. This indeed occurred to me and I found the experience thoroughly disheartening. Whilst I am certain that those who have lived

long and active lives receive a biopic of the Cecil B. DeMille persuasion, widescreen and in Technicolor, I was treated to

a brief black-and-white short, apparently shot on standard-eight stock with a handheld camera and directed by some inept film

student with no concept of plot. It appeared that I had done nothing whatever of interest or note and that the substance of

my life was destined to be filed away upon some high shelf in a dark corner of the Akashic Records Office, there to gather

dust for evermore. Which was as dispiriting a prospect as the actual experience itself had been.

My final glimpse of life and the living was of the pier above and Enid looking down from it. The leader of the Canvey Island

Mods had his arm about her shoulders. And Enid was laughing.

And then the waters closed above my head.

And I sank beneath them.

And I became dead.

And sought to take issue with God.

I have small remembrance of what happened next. I have vague impressions, but these take more unrecognisable forms than Gary

Oldman.

I returned from death to find myself in a curious room, towels about my head and shivering shoulders, a crystal tumbler of

Scotch in my trembling hand, a large and awesome figure towering above me.

‘Who are you?’ I managed to enquire.

‘I am your deliverer,’ he said.

‘Are you God?’ I asked. ‘Because if you are, I wish to register my extreme disapproval.’

The towering figure laughed. ‘I am not God,’ said he, ‘although in this life I am probably as close to being a God as it is

possible to be.’

‘Then I am not dead,’ I said.

‘But you were. I rescued you from the sea and applied certain techniques known only to myself in order that I bring you back

to life.’

‘The sea,’ I said and took to the swallowing of Scotch.

‘Gently,’ said the towering figure. ‘That is a fifty-five-year-old single malt from the cellars of Lord Alan Mulholland of

Hove, to be savoured respectfully from the glass, not gulped away like workman’s tea from a chipped enamel mug.’

I savoured and shivered and tried to take stock of my situation. My deliverer seated himself and I took stock of him also.

He was a considerable being, big and broad with a great shaven head, upon the crown of which was a tattooed pentagram. The

face of him was heavily jowled, with hooded eyes and a hawkish nose of noble ilk. He was all over fleshy with a girthsome

belly and colossal hands, upon which twinkled great silver rings engraved with enigmatic symbols. A suit of green Boleskine

tweed encased his ample frame. Brown and polished Oxfords clothed his size-twelve feet. The collar of his shirt was starched,

a red silk cravat was secured in place by an enamel pin with Masonic entablatures, and watch chains spanned his waistcoat.

There was indeed a ‘period’ feel to this mighty fellow, as if he had stepped straight from the nineteen thirties, and there

was something more to him, also. A certain something. A certain … charisma.

‘I have not introduced myself,’ he said. ‘I have been known by many names. The Logos of the Aeon. The Guru’s Guru. The Greatest

Man Who Ever Lived. The All-Knowing One. The Perfect Master. In my present engagement, I am the Reinventor of the Ocarina.

The Mumbo Gumshoe. The Hokus Bloke. The Cosmic Dick. The Lad Himself. So many appellations, and all falling short of the mark.

My given name, however, is Hugo Artemis Solon Saturnicus Reginald Arthur Rune. But you may call me “Master”.’

I savoured further Scotch and did noddings of my now bewildered head.

‘And what might your name be?’ he asked.

‘My name?’ I thought about this – indeed, gave it considerable thought – but my name had gone. I had no recollection of it

whatever. I put down my Scotch and patted at my pockets.

‘Searching for your wallet?’ said Mr Rune. ‘Lost to the sea, I suspect.’

‘But I—’ And I scratched at my towel-enshrouded head. ‘I cannot remember my name. I have lost my memory.’

‘It will no doubt return presently. More Scotch?’

I nodded bleakly and did rackings of the brain. I had lost my memory. I had no recollection of who I was, where I lived or indeed what I had been doing wherever I had just been

doing it. Although I remembered something of the sea.

‘You are in Brighton,’ said Mr Rune, refreshing my glass, ‘in my rooms at forty-nine Grand Parade. Our paths have not crossed

by accident. We are all subject to the laws of karma. It is therefore certain that you would have found me sooner or later,

but it is convenient that you should have done so now, rather than later, as it were.’

‘I fail to understand.’ I was shivering more than ever now and Mr Rune was coming in and out of focus. I was far from well,

which was hardly surprising as I had so recently been dead.

‘I do not think I can talk any more,’ I said. ‘In fact, I think I am going to—’

Pass out.

And I did.

I awoke the next time to discover myself in a cosy room. I lifted the covers of the cosy bed to discover myself naked beneath

them. And for a moment I smiled somewhat, because now I did recall that I was in Brighton with a girlfriend whose name momentarily

eluded me.

I turned to view this lovely and to make certain suggestions as to how we might begin our day.

But I found myself alone.

And bewildered.

And then the door to the cosy room opened and a great big man walked in. And the terrible circumstances of the previous night

(well, some of them, at least) came rushing back.

‘Mister Hugo Rune,’ said I and took to shivering once again.

‘Rizla,’ said Mr Rune, ‘I have brought you breakfast.’

‘Rizla?’ I said and I shook my head. ‘I do not think that my name is Rizla.’

‘So what might it be, then?’ Mr Rune placed a tray upon a bedside table, a tray generously burdened with a fry-up of heroic

proportions.

‘My name is—’ And my memory returned to me – not of my name, but of the memory that I could not remember it. So to speak.

‘Fear not,’ said Mr Rune, ‘it will return. But for now Rizla is as good a name as any.’

‘It’s not,’ I protested. ‘It’s a rubbish name.’

‘It will serve for the present. Enjoy your repast.’

And he departed, slamming the door behind him.

I ate and I cogitated. The meal restored my body, but I remained troubled to my very soul. I did not know who I was, where

I had been born, whether I had family or not. It was a horrible thing to experience and it brought me nearly to the point

of tears. I maintained, however, a stiff upper lip. Of one thing I did feel certain: I was a brave young man, fifteen to sixteen

years of age, by my reckoning, and I also felt certain that I would soon clear up the matter of my identity and return to

wherever I had come from and into the arms of those who loved me.

Assuming that there were those who loved me.

I felt some pangs of sadness and doubt regarding this. Perhaps I was an orphan boy. Perhaps my childhood had been the stuff

of horror. Perhaps I had done questionable things.

The door opened and Mr Rune stuck his overlarge head around it. ‘Such thoughts will give you a headache,’ said he, ‘and no

practical good will come from them. Finish your breakfast and join me in my study. We have matters to discuss.’

I did as I was bid, wrapped myself up in the bed sheet and joined Hugo Rune, who was sitting in his study. I had taken in

certain details of this curious room upon the previous night, but now, with sunlight tumbling in through the casement windows,

I was afforded a clearer view of it and absorbed fully its true and wondrous nature.

The room was well furnished with comfortable chairs of the Victorian persuasion and much period knick-knackery in the shape

of mysterious curiosities. There were beasts encased by domes of glass that looked like mythical creatures to me, and there

were canes and swords and muskets, too. I spied a brass astrolabe and numerous pieces of ancient scientific equipment, all

brazen cogs and ball-governors. An ornate oak dining table surrounded by heavily carved Gothic chairs stood near a decorative

drinks cabinet, and there were many, many leather-bound books on shelves and in piles and willy-nilly here and there and in sundry other places. One wall

was all but covered by a great street map of Brighton, and upon this map were traced a number of figures resembling men and

animals, following the lines of various roads, which put me in mind of pictures I had seen of the Nasca Plains. Which cheered

me slightly, because it meant that there were some things that I could remember – books I had read, things that I had seen

– although as to where and when, these details remained a mystery.

‘What an extraordinary room,’ I observed. ‘You must surely have travelled all over the world to have amassed such an eclectic

collection of ephemera.’

Mr Rune clapped his great hands together. ‘Excellent,’ said he. ‘An articulate young man – a rare thing indeed in this benighted

age. Sit yourself down next to me.’

I settled myself into the comfortable chair with which I had made my acquaintance the previous night. ‘I still feel unwell,’

I said. ‘And I think I should not be taking up your time. As soon as I am dressed I will be off upon my way. If you saved

my life, sir, then I thank you for it, but I must go now and somehow find out who I am.’

‘And how do you propose to go about this?’ Mr Rune held a schooner of sherry in one hand, and although I felt that it was

somewhat early in the morning to be drinking, clearly he did not. He tossed the sherry down his throat and repeated, ‘How

do you propose to go about this?’

‘I will call in at the nearest police station and report myself missing,’ I declared.

Mr Rune laughed a big laugh deep from his belly regions. ‘That should be entertaining,’ he said. ‘I hope you won’t mind if

I accompany you to the police station. I have some business there myself.’

‘I have no objections whatever,’ I said.

‘Good,’ said he. ‘Good. But before we do so, let me suggest to you that we don’t.’

‘Oh?’ said I. ‘And why not?’

‘Well,’ said Mr Rune, ‘if, as has already troubled your mind, you have loved ones, they will surely shortly report you missing.

Would you not think this probable?’

‘I would,’ I said.

‘Then perhaps you should wait for them to do so. Keep an eye out for articles in the newspapers regarding missing persons.

Wait for your photograph and name to turn up.’

I made doubtful sounds.

‘Perhaps you need the toilet,’ said Mr Rune.

‘They were not those kind of doubtful sounds.’

‘Pardon me.’

‘I still think the police station would be the best option.’

Mr Rune did noddings of the head. ‘The policemen might fingerprint you,’ he suggested.

‘They might,’ I said.

‘Which could prove calamitous should you turn out to be a criminal on the run from justice.’

‘I am no criminal!’ said I and rose from my chair, losing both my bed sheet and my modesty in doing so. I hastily retrieved

the sheet and took to re-covering myself.

‘Are you absolutely certain of your innocence?’ Mr Rune arched a hairless eyebrow. ‘Perhaps it is fortuitous that you have

forgotten who you are. Perhaps you do not wish to remember your name.’

‘Nonsense,’ I said. ‘I am no criminal. I know that I am not. I am honest, me. I would surely know if I was not.’

‘You might not be being honest with yourself.’

‘I want my clothes,’ I said. ‘I want to leave.’

Mr Rune set his empty glass aside and took to the filling of the largest smoking pipe that I felt certain I had ever observed.

‘You’re not really certain about anything,’ he said, looking up at me between fillings. ‘I have an offer that I wish to make to you. As I told

you last night, I do not believe that our paths have crossed through chance alone. I do not believe in chance. Fate brought

you to me. I saved your life and I did so that your life should receive a purpose that it previously lacked. Throw in your

lot with me and I can promise you great things.’

‘What manner of great things?’ I enquired.

‘Great things of a spiritual nature.’

‘I do not think that I am a particularly spiritual kind of a fellow,’ I said. ‘I am a teenager and I do not believe that teenagers are noted for their spirituality.’

‘Would a financial incentive alter your opinion?’

‘I wonder whether I already have a job,’ I wondered aloud, ‘or whether I am still at school.’

‘All will eventually resolve itself. Of that I am certain.’

‘Look,’ said I, ‘I appreciate the offer, but I do not know you and you do not know me. On this basis alone I feel that the

throwing in of our lots together might prove detrimental to both of us.’

‘One year,’ said Mr Rune. ‘One year of your life is all I require.’

‘One year?’ I said. ‘That is outrageous.’

‘One month, then.’

‘My memory might return at any moment,’ I said.

‘Indeed it might,’ said Mr Rune, ‘but I doubt it.’

‘Hold on,’ I said. ‘You’re not a homo, are you?’

Mr Rune now raised both hairless eyebrows simultaneously and then drew them down to make a very fierce face. ‘Sir,’ said he,

‘no man calls Rune a homo and lives to tell the tale.’

‘No offence meant,’ I said.

‘And none taken,’ said Mr Rune, calming himself. ‘Some of my closest acquaintances have been of that persuasion. Oscar Wilde—’

‘Oscar Wilde?’ I said.

‘One month,’ said Mr Rune. ‘A month of your time. Should your memory return to you within this period, then, should you choose

to do so, you may go upon your way.’

I must have made a doubtful face, although of course I could not actually see it myself. ‘I am assuming that you are offering

me employment,’ I said. ‘What exactly and precisely would the nature of this employment be?’

‘Amanuensis,’ said Mr Rune. ‘Chronicler of my adventures, assistant, acolyte.’

‘Acolyte?’ I put a doubtful tone into my voice to go with the look I felt certain I was already wearing on my face.

‘I am set upon a task,’ said Mr Rune, ‘a task of the gravest import. The very future of Mankind depends upon the success of

its outcome.’

‘Oh dear,’ I said, softly and slowly, in, I felt, befitting response to such a statement.

‘Never doubt me,’ said Mr Rune. ‘Never doubt my words. During the course of the coming year I will be presented with twelve

problems to solve, one problem per month. Should I solve them all, then all will be well. Should I fail, then the fate that

awaits Mankind will be terrible in the extreme. Beyond terrible. Unthinkable.’

‘Then it is probably best that I do not think about it.’ I rose once more to take my leave, clutching the sheet about my person.

‘I can promise you excitement,’ said Mr Rune. ‘Danger and excitement. Thrills and danger and excitement. And an opportunity

for you to play your part in saving the world as you know it.’

‘I do not yet know it as well as I would like,’ I said. ‘I think I should be off now to get to know it better.’

‘Go,’ said Mr Rune. ‘Go. I evidently chose poorly. You are clearly timid. You would be of no use to me.’

I was already at the door. But I turned at the word ‘timid’. ‘I am not timid,’ I said. ‘Careful, perhaps. Yes, I am certain

that I am careful. But certainly not timid.’

‘You’re a big girlie.’ Mr Rune rose, took himself over to the drinks cabinet and decanted more sherry into his glass. ‘Be

off on your way, girlie boy.’

My hand was almost upon the handle of the door. ‘I am not timid,’ I reiterated. ‘I am not a big girlie boy.’

‘I’ll pop around to the labour exchange later,’ said Mr Rune, returning to his chair and waving me away. ‘Put a card up on

their help-wanted board: “Required, brave youth, to earn glory and wealth”, or something similar.’

‘I am brave,’ I protested. ‘I know that I am brave.’

‘Not brave enough to be my assistant, I’m thinking. Not brave enough to be my partner in the fight against crime.’

‘Crime?’ I said. ‘What do you mean by this?’

‘Oh, didn’t I mention it?’ Mr Rune made a breezy gesture, the breeze of which wafted across the room towards me and right

up my bed sheet, too. ‘I am a detective,’ said he, drawing himself to his feet. ‘In fact, I am the detective. I solve the inexplicable conundrums that baffle the so-called experts at Scotland Yard.’

‘You are a policeman?’

‘Heavens, no. I am a private individual. I am the world’s foremost metaphysical detective.’

‘Like Sherlock Holmes?’

‘On the contrary. He was a mere consulting detective and he would have been nothing without me.’

I raised an eyebrow of my own. A hairy one.

‘Go,’ said Mr Rune. ‘I tire of your conversation.’

‘No,’ I said. ‘I am not timid. I am brave. And I am not going.’

‘You wish then that I should employ you?’

I chewed upon my bottom lip. ‘I don’t know,’ I said.

‘Timid and indecisive,’ said Mr Rune.

‘Count me in,’ I said.

‘You will be required to sign a contract.’

‘Count me in.’

‘In blood.’

‘Count me out.’

The Hangleton Hound

PART I

I did sign Mr Rune’s contract, and I signed it in blood.

I don’t know exactly why I did it; somehow it just seemed to be the right thing to do at the time. Ludicrous, I agree; absurd,

I also agree; and dangerous, too, I agree once again. And perhaps that was it – the danger.

I did not know who I was.

I did not know who Mr Rune was.

And even now, some one hundred years later as I set pen to paper and relate the experiences and adventures that I had with

Hugo Rune, I cannot truly say that I ever actually knew whom or, indeed, what he really was.

Although—

But that although is for later.

For the now, from that day before yesterday to which I had been returned from the dead, I inhabited rooms at forty-nine Grand

Parade, Brighton, in the employ of Hugo Artemis Solon Saturnicus Reginald Arthur Rune, Mumbo Gumshoe, Hokus Bloke, Cosmic

Dick, Lad Himself and the Reinventor of the Ocarina.

And he and I were bored.

Perhaps the life of ease and idleness had never appealed to me. Perhaps I had never experienced it before and therefore did

not know how to appreciate it properly.

Perhaps, perhaps, perhaps.

On the day that I had signed Mr Rune’s contract, with blood drawn from my left thumb, he had taken me off to the tailoring

outlets of Brighton and had me fitted with several suits of clothes. I recall that no money exchanged hands during these transactions

and that there was much talk from Mr Rune about ‘putting things on his account’. And much protestation from the managers of

the tailoring outlets. But somehow we gained possession of said suits of clothes and I became decently clad and most stylishly

clad, also. Which Mr Rune explained was just as one should look when one engaged in regular dining out.

Dining out was evidently one of Mr Rune’s favourite occupations. The man consumed food with the kind of gusto with which a

Blue Peter presenter might consume cocaine.* Mr Rune really knew how to put the tucker away. And he did it, as he did everything else, with considerable style. Although,

sadly, he enjoyed the most rotten luck when it came to restaurants. No matter where we dined, and I recall that we never dined

in the same restaurant twice for reasons that I will now explain, the outcome of each meal was inevitably the same. Mr Rune would fill himself to veritable excess, consuming the costliest viands upon the menu, along with the most expensive

wines on offer, and would sing the praises of the chef throughout the consumption of each dish.

And then, calamity.

We would be upon our final course – the Black Forest gâteau or the cheese and the biscuits – when Mr Rune would be consumed

with a fit of coughing. I would hasten to his assistance, patting away at his ample back and thereby mercifully sparing him

a choking as he coughed up a bone.

A rat bone!

I genuinely felt for the fellow. How unfair it was that it should always be he who suffered in this dreadful fashion, he who appreciated his food so much, who chose only to dine in the most exclusive restaurants. Our evening would be well and

truly spoiled. Words would be exchanged, harsh words on the part of Mr Rune, words which included the phrases ‘a report being

put in to the Department of Health’ and ‘imminent closure of this establishment’.

On the bright side, I never saw Mr Rune actually pay for a meal; indeed, on occasion he received a cash sum in compensation

for the unfortunate incidents. And, hearty and unfailingly cheerful as the man was, he always wore a smile when he and I walked

away from the restaurant in question.

We dined out, and we purchased clothes and sundry other necessities, mostly of an extravagant nature, and always ‘on account’,

but if the solving of crime was Mr Rune’s métier, then it appeared that either there was no crime at all upon the streets of Brighton to be solved, or that it was all being

amply dealt with by the local constabulary. No one, it seemed, required the talents of ‘the world’s foremost metaphysical

detective’.

I had been with Mr Rune for three weeks now and I was no nearer either to recovering my memory or to aiding him ‘to solve

the inexplicable conundrums that baffle the so-called experts at Scotland Yard’. Although I had heard him play the ocarina

many times.

Upon this particular day, an unseasonably sunny day in March, Mr Rune and I lazed in deckchairs upon Brighton beach enjoying

the contents of a hamper that had recently arrived from Fortnum and Mason, for which Rune had failed to pay cash on delivery due to some oversight upon the part of his banker that would be dealt

with at the earliest convenience.

‘I do not wish to complain,’ I said to Mr Rune, ‘for I am certainly enjoying my time with you and I am sure that I have never

been so well dressed and well fed in my life, but I do recall you saying that you would have cases to solve, the outcome of

which would save Mankind as we know it, or some such thing.’

‘I will pardon your lapse from articulacy upon this occasion,’ said the Logos of the Aeon, adjusting his sunspecs and straightening

the hem of the Aloha shirt he was presently sporting, the one with the bare-naked ladies printed upon it. ‘I assume it to

mean that you are presently piddled.’

‘Are you suggesting that I am drunk?’ I enquired.

‘You have imbibed almost an entire bottle of vintage champagne, one of the finest that salubrious establishment, Mulhollands

of Hove held in their reserve stock.’

‘You drank the first bottle without offering me any.’

‘The thirst was upon me. I abhor inactivity.’

‘That is what I am talking about. Where are these exciting cases of which you spoke? What about the danger and adventure?’

‘Marshal your energies, for these things will shortly come to pass.’

‘But when?’

Rune drew in a mighty breath and sighed a mighty sigh. Bare-naked ladies rose and fell erotically upon his bosom. ‘No one

knocks,’ said he. ‘I would confess to perplexity if I did not bow to inevitable consequence and fortuitous circumstance and

understand how the transperambulations of pseudo-cosmic anti-matter shape the substance of the universe.’

‘I have no idea what you are talking about,’ I said. And I did not.

‘All right,’ sighed Mr Rune. ‘Cast your eye over this and give me your considered opinion. Your considered opinion only – do we understand each other?’

‘Not very often,’ I said and snatched at the object that Rune tossed in my direction. It was an envelope.

‘I retrieved it from my post-office box this very morning,’ said the Cosmic Dick, by way of small expl

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...