Page was not found.

Synopsis

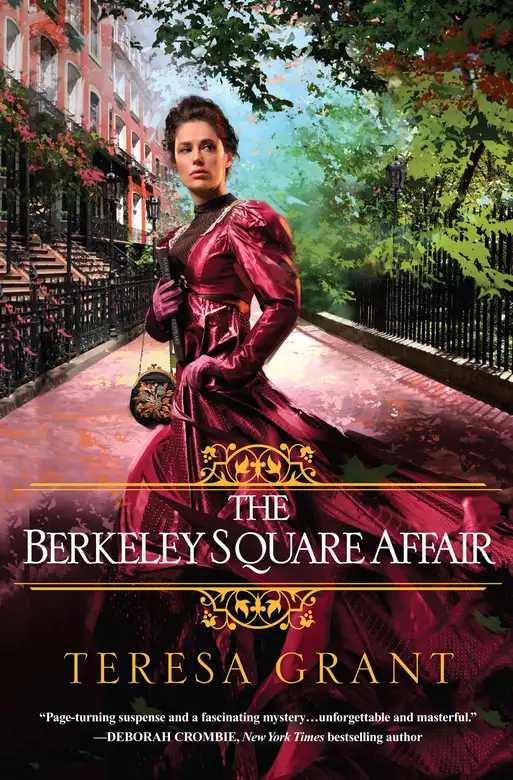

In 1817 London, a stolen treasure may hold a clue to a ghastly crime: “Page-turning suspense and a fascinating mystery . . . Masterful.” —Deborah Crombie, New York Times–bestselling author of A Bitter Feast

Ensconced in the comfort of their elegant home in London’s Berkeley Square, Malcolm and Suzanne Rannoch are no longer subject to the perilous life of intrigue they led during the Napoleonic Wars. Once an Intelligence Agent, Malcolm is now a Member of Parliament, and Suzanne is one of the city’s most sought-after hostesses. But a late-night visit from a friend who’s been robbed may lure them back into the dangerous world they thought they’d left behind . . .

Playwright Simon Tanner had in his possession what may be a lost version of Hamlet, and the thieves were prepared to kill for it. But the Rannochs suspect there’s more at stake than a literary gem, for the play may conceal the identity of a Bonapartist spy—along with secrets that could force Malcolm and Suzanne to abandon their newfound peace and confront their own dark past . . .

Praise for Teresa Grant’s The Paris Affair

“Twists and turns galore, swashbuckling adventure and suspense throughout . . . for readers in search of smart historical mysteries.” —Tasha Alexander, New York Times–bestselling author

“I loved this book! Superb!” —Deborah Crombie, New York Times–bestselling author

“Unravel the secrets and lies at the heart of an almost impenetrable mystery . . . Thrilling!” —Deanna Raybourn, New York Times–bestselling author

“A treat . . . Readers will be holding their breat

Ensconced in the comfort of their elegant home in London’s Berkeley Square, Malcolm and Suzanne Rannoch are no longer subject to the perilous life of intrigue they led during the Napoleonic Wars. Once an Intelligence Agent, Malcolm is now a Member of Parliament, and Suzanne is one of the city’s most sought-after hostesses. But a late-night visit from a friend who’s been robbed may lure them back into the dangerous world they thought they’d left behind . . .

Playwright Simon Tanner had in his possession what may be a lost version of Hamlet, and the thieves were prepared to kill for it. But the Rannochs suspect there’s more at stake than a literary gem, for the play may conceal the identity of a Bonapartist spy—along with secrets that could force Malcolm and Suzanne to abandon their newfound peace and confront their own dark past . . .

Praise for Teresa Grant’s The Paris Affair

“Twists and turns galore, swashbuckling adventure and suspense throughout . . . for readers in search of smart historical mysteries.” —Tasha Alexander, New York Times–bestselling author

“I loved this book! Superb!” —Deborah Crombie, New York Times–bestselling author

“Unravel the secrets and lies at the heart of an almost impenetrable mystery . . . Thrilling!” —Deanna Raybourn, New York Times–bestselling author

“A treat . . . Readers will be holding their breat

Release date: March 25, 2014

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 476

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Unlock full access – join now!

OrBy signing up, you agree to our Terms of Service, Talk Guidelines & Privacy Policy

Have an account? Sign in!