- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

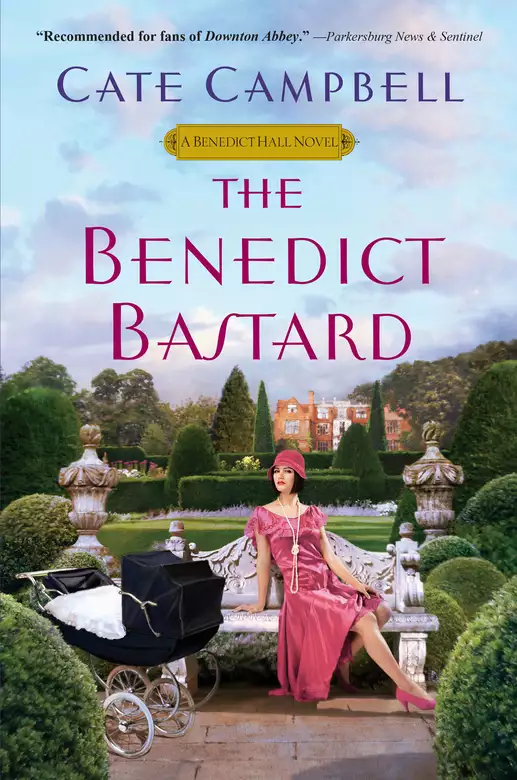

"Recommended for fans of Downton Abbey." --Parkersburg News & Sentinel

Set against the vibrant and colorful backdrop of 1920s Seattle, Cate Campbell's latest Benedict Hall novel brings the tumultuous, changing world of a privileged family to vivid life. . .

Though born into one of Seattle's most prestigious families, Margot Benedict has fought to claim all the independence offered to young women in 1923. Where her brother Preston embraced a life of debauchery, Margot has a thriving medical practice. Working at a local orphanage, she's shocked to see a young boy who looks every inch a Benedict. But though she's convinced this is the illegitimate child Preston once mentioned, Margot has no way to prove any family connection.

At sixteen, Bronwyn Morgan fell in love with dashing Preston Benedict. Seduced and abandoned, she's arrived at Benedict Hall determined to find the son she was forced to give away. Aging matriarch Edith takes the fragile girl under her wing, but Edith's own delicate state and Preston's dangerous animosity collide, jeopardizing not only a child's future, but the Benedict legacy itself.

Praise For Benedict Hall

"Entertaining, with a well-drawn backdrop." --RT Book Reviews

"Full of drama. . .great characters with warm chemistry the reader will want to see together." --Parkersburg News & Sentinel

"Intriguing and colorful." --The Seattle Times

Release date: August 26, 2014

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 372

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Benedict Bastard

Cate Campbell

Fortunately, her maid was a wizard at dealing with that. And had plenty of experience.

Bronwyn leaned against the brick wall, crossing her silk-stockinged legs and brandishing the Bakelite holder like a scepter. Johnnie pushed his way toward her through the throng, holding their drinks aloft in his two hands and turning sideways to fit his bulk between the chairs. He grinned as he caught sight of her. He evaded the waving arms and tossing heads, managing somehow to set the cocktails down without spilling. He collapsed onto a chair that was much too small for him, and dashed at the perspiration dripping down his cheeks. “Gosh!” he cried. His voice was barely audible above the tinny plonk of the player piano’s keys. He leaned close to make himself heard, enveloping Bronwyn in a gust of gin-scented breath. “I think half the town is down here!”

Bronwyn picked up her cocktail and eyed it, tipping it this way and that.

“It’s a Fallen Angel,” Johnnie bellowed. “That’s your drink, isn’t it? A Fallen Angel?”

“It doesn’t look like one,” Bronwyn said doubtfully. “Gin and lime and crème de menthe? It should be green.”

“Well—it’s sort of green.” Johnnie peered at the cocktail. “Willy said it was a Fallen Angel.”

Bronwyn shrugged. “Never mind,” she said.

“What?”

She waved her hand, and took a sip of the drink. It wasn’t a real Fallen Angel, though Willy, the barman, had tried to make up for the deficit of crème de menthe by adding sugar syrup. At least here at the Cellar she could trust the gin. As she had laughed to Johnnie the last time, they could trust the gin at the Cellar because Willy made it in his very own bathtub.

“Come on, Bron, let’s cut a rug,” Johnnie said. He tossed back his own drink, which was probably straight gin—Johnnie wasn’t the discerning sort, which was why he was content to squire Bronwyn Morgan around the speakeasies of Port Townsend. He jumped to his feet and reached for her hand.

“I don’t see where,” she protested.

“We’ll make room, over there in the corner. Come on, we’ll put another nickel in the piano. Everybody wants to see you do the Black Bottom!”

Bronwyn polished off the drink, grimacing at the bite of rough gin and sour lime. The taste didn’t really matter. It would have been nice to have a real Fallen Angel, like the ones people drank in New York and Seattle, but gin and dancing were why she had come to the Cellar. Gin, awkward dancing, loud voices, bad music, bad company—they irritated her enough to distract her from the other irritants in her life. She got to her feet, and Johnnie gripped her hand to pull her through the crowd.

People nodded to her and spoke her name as she wound among them. Most of them called her Bronwyn, because she was by far the youngest woman in the place. There were a few—men mostly—who called her Miss Morgan. They were the ones who would no doubt mention having seen her, stirring afresh the embers of her father’s wrath. She smiled brazenly at each of them, and flourished the cigarette holder. When the Black Bottom began, she threw herself into the steps, making her skirt swirl to show the satin garters clasped around her thighs.

She liked the Black Bottom, because it had no rules. The dancer didn’t have to touch her partner—in the case of Johnnie Johnson, this was preferable—and she was limited only by her own talent for movement. Bronwyn knew her personal faults very well, assisted in her understanding by her father’s frequent reminders, but she also knew her strength, and it was dancing. The foxtrot, the rhumba, the swooping steps of the tango, all came as naturally to her as walking.

It was what had first drawn Preston to her, at the Bartletts’ reception three years before. She had been dancing.

On that day, in the summer of 1920, she hadn’t worn garters or carried a cigarette holder. She had dressed in the most modest of afternoon frocks, a drop-waisted georgette with a scarf hem and a lace-edged collar with long points. She had recently cut her hair in the Castle Bob, and her mother had allowed her a touch of lipstick. She was sixteen, but she was certain she looked at least eighteen. She had just been accepted into the Cornish School, and she was feeling very grown-up, a young woman with the world at her feet and a shining future.

Now, at nineteen, she understood that the younger Bronwyn had been as naive as a kitten. She had believed that an older man’s attention, the shine of admiration in his eyes, the way he watched her every movement, meant he had fallen in love with her. And she had—dizzyingly, breathlessly, passionately—fallen in love with him. He was a decorated war hero. His family was even wealthier and more respectable than her own. His dancing made her feel like a creature made of cloud, swirling as weightlessly as a puff of mist.

She was older and wiser now, and neither condition brought her much joy. She swung into the hip-thrusting motions of the Black Bottom, knowing that her father hated this dance. He said it was because he didn’t like girls flinging themselves about, but Bronwyn understood it was the sensuality that offended him. She hadn’t known the Black Bottom when she was sixteen. She wouldn’t have understood it.

Someone put another nickel into the piano, and a Charleston began. Without bothering to see if Johnnie joined her, Bronwyn began the dance. It took more space than the Black Bottom, but people stepped back to give her room. The rhythm swept her up. She was adept at the sliding kick-step, the shimmy, the coordination of hands and knees and feet. Her heeled pumps skimmed the floor, and her beaded dress shimmered. Johnnie tried to keep up, but his big body was awkward, and his efforts made her laugh. She knew every step, having seen all the films, with a pianist beneath the screen inventing tunes to match the dance. Bronwyn had invented a few of her own steps, too, which would no doubt soon show up at someone’s debutante ball or engagement party.

Someone else would have to demonstrate them, though. She wouldn’t be invited to these events. Her parents had fooled no one by sending her to Vancouver. No one in Port Townsend would mention the matter in the presence of Chesley and Iris Morgan, but everyone knew their daughter was ruined. No matter how frantically she danced, no matter how many Fallen Angels she drank, she couldn’t pretend otherwise.

Still, she couldn’t hate him. She had loved Preston Benedict. She was still in love with his memory.

In that faraway summer of 1920, everyone Bronwyn knew was giddy about the new decade and the unfolding of a peacetime era. Port Townsend was recovering from the collapse that had threatened the city twenty years before. Businessmen were growing fat on the boom in lumber sales, and planning their profits from the new paper mill. The more daring among them padded their incomes by importing Canadian liquor for the speakeasies in Seattle. The boys who made it safely home from the war were celebrated as heroes, and had their pick of Port Townsend beauties.

Bronwyn and her friends read Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar and planned their debuts. They cut their hair and rolled their stockings, and tried, in secret, to learn to smoke cigarettes. They liked to think of themselves as daring, independent women of the new century, but in truth, they were very like their mothers. They understood the rules of their social circle. Though they cast off their corsets and shortened their dresses, their magical girlhoods were meant to end, inevitably, in fairy-tale weddings.

None of the girls gave much thought to what came after. There would be honeymoons. They were expected to know how to choose menus and entertain guests. They would learn to manage maids and cooks and laundresses. To Bronwyn and her friends, marriage was just a grown-up version of playing house.

Their fathers treated them like dolls on a shelf, to be seen and admired until they would, one day, be plucked down and settled on a different shelf. Their mothers watched over them like swans over their cygnets, guiding their steps, protecting their good names, eyeing the young men to sort out the ones with the best prospects. Both mothers and fathers believed, as their own parents had, that the less girls knew, the better off they were.

The girls grew up in blissful ignorance of their own physiology. They were told their monthly periods were the curse of women. No one explained why, or how they were connected to the great mystery.

Bronwyn’s view of romance was more Jane Austen than D. H. Lawrence, more Snow White than The Scarlet Letter. The union of men and women was a misty, magical idea, a fantasy of white silk and flowers, of veils and pearls and wedding cakes. She knew nothing of the realities of flesh and blood, of passion and pain, or of treachery.

Such a lovely June day it had been, when Bronwyn and her friends Bessie and Clara clustered near the French doors of the Bartletts’ ballroom, giggling and whispering together. Their mothers were nearby, but the girls were doing their best to ignore them.

Bessie nudged Bronwyn. “Don’t you just love a man in uniform?” Bessie was wearing a dress with a high collar, to hide the reddish freckles that so embarrassed her. Bronwyn and Clara had found a recipe for her, a paste of rye and tartar and oil of roses, but it wasn’t working.

Clara said, “The Bartletts invited all the officers up from Fort Worden.” She blushed as she said it, and turned her back on the knot of young men gazing around the room.

Bronwyn looked past her at the reception line, where the Bartletts stood with their daughter Margaret. The party was in Margaret’s honor, to signal the end of her debut year. Margaret had always been plain, but she looked almost pretty today, powdered and pressed and coiffed. The officers bowing over her hand did indeed look handsome, the whole crowd of them, with their shining boots and polished buttons. Bronwyn was about to say so when Bessie whispered, “Who is that?” and the others turned to look at the stranger just entering from the garden.

Time suspended for Bronwyn. The soldiers in their uniforms faded from her consciousness, vanquished by this new arrival. He paused in the doorway, and her heart paused with him.

The afternoon sun burnished his pale hair to gold. His suit was the latest cut, broad shoulders, pleated trousers, a vest of taupe silk. In his breast pocket, just peeking out so everyone could see it, was a notebook and pen. He was not particularly tall, but his features were finely cut, and his eyes—oh! Such a clear, pale blue, shining even across the crowded ballroom.

Bessie hissed in Bronwyn’s ear, “D’you know who that is? That’s the newspaperman! The columnist!”

“What columnist?” Bronwyn whispered back. Her mouth had gone dry, and her heart resumed its beat, thudding hotly beneath her silken frock.

“With the Times, silly.” Bessie poked her with an elbow. “He writes ‘Seattle Razz.’ Everyone’s reading it!”

“He’s the one who writes ‘Seattle Razz’? But he’s so young!”

Bessie shrugged. “Not so young, I guess. I mean, he went to the war and everything. Of course he doesn’t wear his uniform anymore, but Mama says he was a captain in the British Army. Has all sorts of medals and things.”

“Oh . . .” Bronwyn gazed at him in astonishment. She had never seen a more appealing man. He came into the ballroom with a step that was modest, almost diffident, as if he wasn’t sure anyone would notice him. He touched his hair in an absent way, smoothing his forelock back with one finger. It didn’t stay, but fell down again over his forehead, a strand of gold gleaming above those ice-blue eyes.

Bronwyn could hardly breathe past the melting sensation in her breast.

“And,” Bessie went on, parceling out information like sweets from a box, “he’s one of the Seattle Benedicts. You know, the ones who have Benedict Hall. On Millionaire’s Row.”

“Oh . . .” Bronwyn said again. It wasn’t like her to be wordless, or to lose her composure, but this man was nothing like the callow boys she knew, nor even like the grinning soldiers lined up on the opposite side of the ballroom like puppets. He was just—just—perfect.

She could hardly bear to watch him bow over Mrs. Bartlett’s hand, then take Margaret’s. Margaret gave him a coquettish smile, confident in her lace-and-chiffon afternoon frock, her drab hair caught up with loops of pearls.

Pain shot through Bronwyn at the idea that Preston Benedict might take a shine to Margaret Bartlett. Perhaps he would even ask her parents if he could court her. She was the proper age, after all. Her family name was impeccable. Worse, she was looking her best today.

Bronwyn felt a sudden and staggering sense of loss. It made no sense, since she hadn’t even met Preston Benedict, but she yearned toward him nevertheless. He flashed a smile at stupid Margaret before he put out his hand to Mr. Bartlett. Bronwyn wanted to push her way through the crowd and seize his arm.

She knew what her mother would say about him. He was not only too old to be introduced to a young lady who was not yet out, but he was a newspaperman. Iris Morgan maintained that a real lady appeared in the papers only three times in her life: at her birth, at her marriage, and at her death. She might make an exception for a debutante event, perhaps a ball or a fashionable tea. She would never, ever approve of her daughter being mentioned in “Seattle Razz.”

A small band, trumpet, saxophone, and piano, began to play from an inner corner of the ballroom. Young men glanced around in search of partners. George Bartlett, Margaret’s younger brother, started toward Bronwyn, but Iris Morgan, appearing as if from nowhere, stepped between them. Though she blushed at having to assert herself, she said, “No dancing, Bronwyn. Not until you’re out.”

“But, Mother!” Bronwyn cried. “Bessie’s dancing, look! And Clara!”

“I don’t think your father would like it,” her mother said, glancing around as if Chesley might show up at any moment.

“You let me dance at Clara’s birthday party!”

“That wasn’t public.”

“Mother, please! Just let me dance with George. It’s his house, after all.”

Iris hesitated, gazing at her daughter, lifting a hand to smooth a wrinkle in her collar. “I just don’t know . . . I’m afraid . . .”

“Mo-ther! You’re always afraid.”

George reached them at that moment, saying brightly, “Good afternoon, Mrs. Morgan. You look so lovely—you could be Bronwyn’s sister!”

“George, shame on you.” Iris colored, and gave an embarrassed titter. “Such flattery.”

It could have been true, though. Bronwyn and her mother looked much alike. Their honey-brown hair was dressed in identical finger waves, firmly fixed with flaxseed gel. Their eyes were the same hazel, sparkling with flecks of gold. Iris’s skin had grown soft around her chin and throat, but it was still fine-grained and clear.

Bronwyn took advantage of the awkward moment by putting out her white-gloved hand for George to take. “Just one dance, Mother,” she said. “Listen, it’s the new foxtrot! Please.”

Iris didn’t exactly give her permission, but she sighed, and as she pressed an uncertain hand to her embroidered bodice, the young people made their escape onto the dance floor.

George wasn’t much of a dancer, but he was better than nothing. Bronwyn danced the foxtrot with him, then a one-step and the Castle Walk. She felt her mother’s worried gaze on her, but she didn’t look back for fear Iris would make her stop. When she saw Preston Benedict watching, she pretended not to notice, but she made her steps smoother, her turns swifter, the movements of her head and hands as graceful as she could. Her skirt fluttered gratifyingly around her ankles, and the narrow scarf around her throat rippled like a ribbon of cloud.

When Preston cut in, George was forced to give way. A slow waltz began, and Bronwyn, her heart fluttering into her throat, took special care not to catch her mother’s anxious eye. She floated away in Preston’s assured clasp, and knew in her bones that her life would never be the same again. Her fairy tale had begun.

In the bliss of gliding across the dance floor in his arms, of feeling his cheek brush her hair, in the enchantment of being chosen over every other girl in the room, Bronwyn Morgan forgot that every fairy tale has its dark side.

The new automobile had a distinctive smell to it, a scent Margot couldn’t name. She sniffed it curiously as Blake closed her door and climbed into the driving seat. As he pressed the starter, Margot settled herself against the mohair velour, and removed one glove to caress its silken texture. “Do you like it, Blake?”

“Do you mean the motorcar?”

“Yes.”

He glanced at her in the rearview mirror, and reached up to adjust the angle. “Well, Dr. Margot,” he said, his deep voice noncommittal. “It’s certainly a change.”

“Green!” she marveled. “I can hardly believe Father could make such a racy choice.”

“It’s elegant, don’t you think? It’s called a Phaeton. The steering wheel is solid walnut.”

“Very chic.”

“Yes. I believe it’s quite up-to-date.” Blake smiled at her in the mirror as he put the automobile in gear. He pulled out into Fourteenth Avenue, and didn’t speak again until he had safely negotiated the turn. “I recommended the black, but Mr. Dickson wanted something different from the Essex. I believe he hopes Mrs. Edith will bring herself to ride in it.”

“But she rode in the Essex, didn’t she? After the accident, I mean?”

“Only to go to the cemetery. And later, Steilacoom.”

Blake was being tactful. For more than a year, Margot’s grieving mother had hardly set foot outside of Benedict Hall except to visit an empty grave. Everything had changed when she learned her younger son was alive. Nothing would do for her then but to go straight to the state hospital where Preston was being held. Margot and her father feared Edith would break down when she saw how badly Preston was burned, and when she grasped the truth of the terrible things he had done.

They had misjudged her.

Edith made regular visits to see her son until he was moved to a private sanatorium in Walla Walla. That was too far for a day trip, whether by motorcar or by train. Edith was planning to visit, and frequently spoke of it. Margot doubted this was a good idea, but it was the only thing her mother took any interest in. She sent Preston packages from home, she bought him clothes and toiletries, and she kept his place set at the dining table in Benedict Hall, ready for the day of his return.

Margot suspected Edith would have responded the same way if Preston had gone to jail, which was his only remaining alternative. Edith had an infinite capacity for denial where her youngest son was concerned.

Blake interrupted her thoughts. “Do you like the new motorcar, Dr. Margot?”

“I do,” Margot said. “It’s quieter than the Essex. The upholstery is beautiful.”

“Indeed. Very handsome.”

“But green! It seems like a symbol for something. A sea change, perhaps.”

“It has been a year for change,” he said mildly.

“Blake, you’re a master of understatement.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said gravely, and Margot chuckled.

Curious eyes followed them as the sparkling automobile rolled at a majestic pace into the East Madison neighborhood. Small boys stared, and some pulled off their caps in awe. Women with shopping bags turned their heads. Blake behaved as if he didn’t notice, but Margot smiled and waved, winning tentative nods. There was no room to pull over in front of the Women and Infants Clinic, so Blake was forced to stop the Cadillac in the middle of the road. An elderly Negro woman came out of the house across the street to gape at it. Blake tipped his driving cap to her, and she dipped a rather elegant half-curtsy, as if he were royalty. Even Blake had to chuckle at that.

Sarah Church came dashing out to meet them, her nurse’s cape rippling around her. Blake opened the door of the Cadillac, and as she climbed in, he relieved her of the case of medicines she carried. She dimpled at him, and pressed her hand to his arm before she climbed into the back beside Margot.

She perched gingerly on the mohair upholstery, as if afraid her slight weight might mar its smooth surface. “Dr. Benedict,” she breathed. “Your new motorcar is—I mean, it’s just—”

“Isn’t it, though? I think so, too, and so does your neighbor across the street.” She smiled at Sarah, and patted the seat. “Come now, lean back. I’ve been assured we can’t hurt the material by sitting on it. Let’s enjoy this splendiferous ride while we gird our loins for battle.”

“Are we going into battle?”

“I’m afraid so. I’m told Mrs. Ryther is something of a terror.”

“It’s hard to imagine that, considering the work she does.”

“Perhaps you have to be a terror to take on such burdens. How many children does she have now?”

“Over a hundred, I believe.”

Margot shook her head in wonder. “I’d be cranky if I had so many children to watch over. I suppose if she’s difficult we should make allowances.”

Margot leaned back, and gazed out the window at the sparkling day. It was good to be outside the hospital for a few hours, to be driving through the green-boughed streets of Seattle. Spring blossomed all around her, sprawling rhododendrons blazing pink and red, azaleas flashing their starry flowers against the layered greens of fir and pine, cedar and vine maple. Every year, May surprised her with its heady scents and glowing colors, as if the rains of winter had erased its memory.

Nineteen twenty-three was off to a fine start in every way, as far as Margot was concerned. Benedict Hall hummed with life, and it was hard sometimes to know who was where.

Cousin Allison was always in motion, rushing off to her University classes, racing back to snatch up her tennis racket or a stack of books. The family’s telephone rang even more often than Margot’s, almost always for Allison. She had taken to flopping on the floor, so the maids had to step over her legs, until Blake ordered a chair brought from the small parlor so the girl could sit properly for her endless conversations. He had issued strict instructions to the staff that they were not to eavesdrop on these telephone calls, but no one believed those orders had any effect at all.

Little Louisa had begun to walk in earnest, toddling at top speed wherever she went. Nurse followed with her hands outstretched, ready to pick her up when she fell, and trying to prevent her tumbling down the long staircase. Everyone in Benedict Hall doted so on the baby that Nurse had put her foot down about naps and bedtime and what she called “too much excitement.” The excitement, Margot thought, came mostly from Louisa herself, who found entertainment in everything she saw, from the Irish maids’ freckles to Hattie’s long apron strings, which she liked to use for balance as she negotiated the kitchen on her fat, unsteady legs.

Frank had settled nicely into living in the Benedict household, and Hattie, delighted at his young man’s appetite, exerted herself to make his favorite meals. Since he preferred simple dishes, mashed potatoes and roasted meats, Hattie’s skills were shown to better advantage than when she strove for the haute cuisine Edith had ordered in the past. Ramona was too busy with the baby to fuss much over menus, and Edith had lost interest, with the result that the food in Benedict Hall was both plainer and tastier than it had ever been.

And Margot, somewhat to her surprise, loved being Frank’s wife.

She thought about this as they turned north on Stone Way toward the Ryther Child Home. She had feared she wasn’t suited for marriage. She feared giving up her independence, and she worried about diluting the single-mindedness that carried her through the daily challenges of her medical practice. She had found, however, that coming home to Frank in the evenings, sitting close to him as the family gathered to listen to the cabinet radio in the small parlor, climbing the stairs with him at night, sometimes even having time for breakfast with him in the morning, strengthened her. She felt as if she had a foundation from which she could accomplish nearly anything. She was Dr. Benedict all day, and at night if she was called out to a patient. But in the evenings and in the early mornings, at rare social events or when she and Frank slipped out alone, she was Mrs. Frank Parrish, and she liked it very much indeed.

She came out of her reverie as Blake pulled the Cadillac up in front of a large brick building. It had three floors stretching to either side of a formal entrance. Flowers and shrubs filled the front garden, surrounded by a picket fence. Ranks of clotheslines stretched the length of one side of the building. Four surprisingly small children were taking down dry clothes and piling them into a basket. They turned to goggle at the automobile, and at the people emerging from it and turning up the walk.

They did make a sight, Margot supposed. She was taller than most women, and she was carrying her medical bag. Sarah Church, with the box of medicines in her arms, was petite, and very pretty, with bright brown eyes and thick curling hair pinned up beneath her nurse’s cap. Blake, leaning on his cane, insisted on accompanying them, saying he wasn’t sure just what they would find inside.

And of course, Blake and Sarah were Negroes, while Margot wasn’t. That alone would cause a stir.

They paused at the entrance to the house. Sarah said, “I did make a telephone call to Mrs. Ryther to tell her we were coming, but we might be a little early.”

Margot nodded, and knocked briskly on the door.

It opened immediately. A young girl, aged fourteen or fifteen, wearing a voluminous printed apron over a cotton housedress, said in rehearsed fashion, “Hello, and welcome to the Ryther Home.”

“Hello,” Margot said. “Thank you.” She smiled at the girl. “I’m Dr. Benedict, and this is Nurse Church, from the Women and Infants Clinic. And Mr. Blake, our driver.”

“Yes?” The girl didn’t move, and Margot wondered if her job was to keep undesirables from crossing the threshold.

“I believe Mrs. Ryther is expecting us.”

A sudden, childish screech from somewhere in the house made the girl flinch, but she didn’t budge, though more shrieks followed, punctuated by the crash of something like a stack of aluminum saucepans. “Mother Ryther is busy at the moment,” the girl said carefully.

“It sounds like it,” Margot said.

The girl’s composure cracked just a little. She gave a small shrug, and pleated her apron with her fingers. “It’s bath day. The little ones never like it.”

Sarah moved forward, and Margot stepped to the side, out of her way. Sarah had spent the past year working with mothers and babies, and Margot was happy to let her take control of this interview. “May we come in?” Sarah asked directly.

The girl in the apron gazed at her, her mouth a little open. Probably she had never spoken to a Negress before. In this neighborhood, colored people were rare, unless they were servants. The Ryther Home couldn’t afford servants. Mrs. Olive Ryther—everyone called her Mother Ryther, even the newspapers—cared for her charges with just three matrons to assist her. She was famed for wringing contributions out of every business and charity in the city, and even this sprawling house had been built by soliciting donations. “Buy a brick for the Ryther Home,” had been the slogan. Margot was certain her father had paid for several.

Sarah was accustomed to a variety of reactions to her dark skin, and she was more accepting of them than Margot. She said now, in a matter-of-fact tone, “Mrs. Ryther will want to speak to Dr. Benedict. It’s about vaccinations. And money.”

The girl’s gaze drifted from Sarah’s youthful face to Blake’s lined and grizzled one. She said in a distracted way, “I guess. I just don’t—”

“Why don’t you go and ask?” Sarah said. “We’ll wait here. But do tell Mrs. Ryther it’s Dr. Benedict, from the Women and Infants Clinic.”

Margot added, with a touch of asperity, “And Nurse Church.”

At the girl’s puzzled expression, Sarah said gently, “That’s me. I’m Nurse Church.”

“Oh! I didn’t know—that is, I thought because—” The girl’s cheeks flamed an uncomfortable red, and she took a step back. “Wait, please.” She shut the door with a bit more emphasis than needed, and Sarah cast Margot a rueful glance.

Blake gave his deep chuckle. “Like the Magi,” he said. “Three strangers at the door.”

“And bearing unfamiliar gifts,” Margot said.

They stood on the sunny porch for several minutes, li

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...