Molly

Dear Pepper,

Do you have any idea how depressing it is in this room right now? Your dad can’t look at you for longer than a couple of minutes before falling into tears. You’re not breathing on your own, and I can’t see your bandaged head without remembering that you were recently punched in the brain by the bottom of a swimming pool.

They say you might never wake up.

I’ve spent the afternoon doing exactly what your nurses warned me not to do: looking up stuff on the Internet. You probably know by now that telling me not to do something is a super-effective method for getting me to do that very thing. I wish I’d listened to them. The stats about people who wake up from comas are pretty disheartening.

So I started typing as a distraction. It almost, almost feels like I’m talking to you right now.

Maybe, on some level, you’re listening.

Being in the hospital reminds me of the moment I crushed my foot. I’ve been hobbling around all summer with that cast, and the thing sweated and itched like hell, and the whole time you wanted to know how my foot ended up like that.

“Did you lose a fight with a man-eating crocodile?”

“Did you get in an industrial accident?”

“Did you just get mad at someone and kick a wall?”

Well, consider today your lucky day, because I’m finally spilling the secrets. First, though, I’ll tell you another thing you wanted to know—how I came by my unfortunate nickname at the Keller School.

Picture me, Molly Mavity, twelve years old. Peak awkward years. My head was an uncombed sprinkler of orange doodles. I wouldn’t get braces for another year, but boy could I use them. My face had kind of rebelled, turning splotchy and greasy and pockmarked, which was pretty cruel of the universe to do, in light of everything else. Twelve was not a kind year to me.

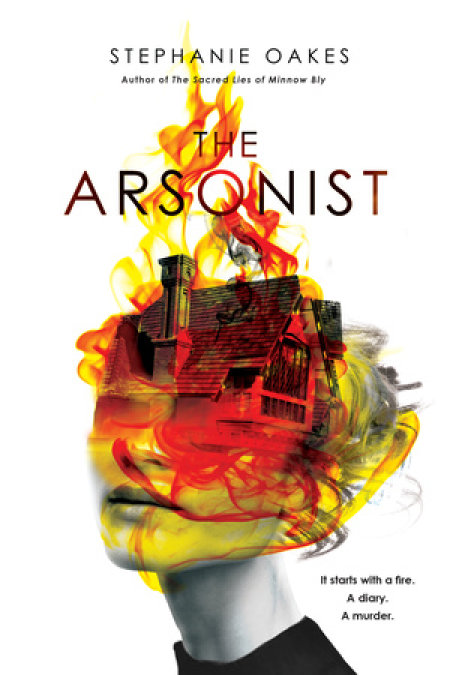

My cousin Margaret also attends the Keller School, and I hadn’t even been there a week before she’d told every girl there about my father, who was in prison awaiting trial for burning six people to death. You remember it, right, Pepper? The Burning Summer, those months when the town would wake up to the smell of smoke, and the police would find the empty shell of a house stuffed in some corner of the city, burned from the inside out. Those were my father’s fires, the fires of the infamous murderer-arsonist of Monterey. The fires that would send him to death row.

My first week at Keller, I discovered a pile of matches in my personal cubby. A group of girls stood nearby, snickering. Not all seventh graders are dungholes of the highest order, but these were. I felt myself boil inside. I wanted to gather the matches, and throw them precisely into their eyeballs so the jelly would run down their faces like I’d seen in an old kung fu movie.

Instead, I picked up two matches, shoved them between my top lip and gum, red heads facing down like bloodied fangs, and turned to the girls. “I vant to suck your blood,” I told them.

They exchanged looks of genuine horror, like they were afraid I would actually go full vampire on them. Strangely, I felt that this reaction was the best thing that I’d accomplished in a long time. That was the day that I discovered my greatest weapon: being a complete weirdo.

Every school has one. The weirdo follows no rules. The weirdo is lawless.

Which leads to how I received my nickname: Milk Pee Mavity.

“How does a person get a nickname like that?” you’ve asked me. “Did you pee into someone’s milk? Did you drink milk that was actually pee?”

No, I didn’t drink pee, Pepper.

It happened like this: I was making my way through the cafeteria line during my first year at Keller. As I reached for a milk carton from one of the crates arranged on the counter, the cafeteria lady said, “Don’t take one of those. They’re about to expire.”

“You’re going to throw them out?” I asked.

“That’s what you do with expired milk.”

I examined one of the cartons. “These don’t expire until tomorrow. And anyway, don’t you know the sell-by dates are just a suggestion? The companies mark them early so they can trick you into buying more.”

The lady sighed. “Wouldn’t you rather have a carton of fresh milk?”

“I’d rather not waste fifty perfectly good ones. A cow had to have her udders sucked on by some metal industrial milker for these.”

“All right,” she said, “if you really want this much milk, it’s all yours. But remember the rule.” She pointed to a sign above the door. no food to be taken out of the cafeteria.

“Game on,” I said.

I lifted the milk crate, walked to my empty table, and proceeded to open carton after carton of milk, draining each in the span of a moment.

In Matilda, when the evil headmistress orders Bruce Bogtrotter to eat an entire cake, the other kids cheer Bruce on. That is not what happened to me. When the girls in the cafeteria began to notice the growing pile of emptied milk cartons scattered across my table, there were no cheers. A hush spread. Soon, the only sound was my labored breath and occasional milk burps. In between cartons, I rested my head on the table like an athlete not sure if they can go on. The cafeteria lady watched me, arms crossed over her chest.

There were only thirty-three cartons, but it didn’t matter. After twenty, my stomach felt like an overinflated water balloon.

At last, by some miracle of human anatomy, I arrived at the last carton. I threw it back and swallowed with difficulty, and as I prepared to lift my arms in the air in victory like an Olympian at the finish line, the bell rang and the other girls dispersed to their classes.

I waddled down the hall to English and eased into my chair just after the bell. At first, I felt okay. As the minutes passed, though, a point somewhere inside my middle began to radiate pain. I jammed my knees together, squeezing every muscle in my nether regions until I was shaking. It was ten minutes before the bell when, leaning over my desk, I raised my hand.

“Miss Markowitz, can I go to the bathroom?” I asked.

Miss Markowitz surveyed me from the front of the room. “You were late to class, Molly, if I’m not mistaken. I’ll just assume that you planned in a bathroom stop during the passing period.”

“But I didn’t,” I said, my voice strained.

“Well, I’m sorry, but that’s your responsibility.”

Well, I’m sorry, but you’re a megalomaniac, I thought. Does it feel good, I wondered, controlling children’s bodily functions? What kind of sick world is this where we can’t allow human beings to relieve themselves without permission?

What happened next was born purely out of spite. Could I have held it? Maybe. But with every second of my bladder paining, I grew more furious at Miss Markowitz, and factory milk farming, and at my aunt for making me come to this messed-up school, and at both my parents for leaving me, and eventually the fury could not be contained. I clenched every muscle, then relaxed them all at once.

“Molly’s peeing!” someone shouted.

Thirty-three milk cartons make a lot of pee, Pepper. The puddle of it crept across linoleum floor of the classroom, and the other students leaped to stand on their seats. Miss Markowitz opened and closed her mouth, at a loss for words.

I wasn’t upset by the noises my classmates were making, or embarrassed by the feeling of pee turning cold against my skin. I was gleeful. I felt strong. I haven’t peed publicly since that day, but I’ve never stopped looking for that feeling. I started calling it the art of not giving a fuck. It is my superpower.

From that point onward, I was Milk Pee Mavity and there wasn’t much point in trying to make friends anymore. And so I wore the badge of weirdness as my distinguishing characteristic, and started spending a lot of time alone.

Which leads to how I crushed my foot back in February.

It was going on five years without anyone to talk to besides my aunt and my one friend, Marty, both decades older than me. Maybe I thought climbing up tall places would make me seem cool. Like somebody might see me up there and think, “There goes Molly Mavity. She peed herself in seventh grade but really she’s a badass. I bet she’s really fun and intelligent, too. Someone you could get a fro-yo with, you know?”

That day, I climbed to the top of the train bridge behind my childhood home on Syracuse Road, the one I lived in before my family split apart like an orange. When missing my mother grew bigger than me, I’d go up there to look at my old house and think of the last time I saw her before she vanished: blond curls pinned to her head with a silk scarf, the cliff of the Château de Nice beneath her, a dead drop of blue behind. My eyes pained at the brightness, but I couldn’t budge my eyes away. My mother was magnetic.

When I heard the rattle of the train, I would’ve almost certainly been fine had I not turned to look at it, kicking my foot out a little. The train wasn’t even moving very fast, but the momentum of it collided with my foot with enough force to, in the burst of a second, shatter almost every bone inside.

Seconds later, I was lying in the salty stream below the bridge, my foot exploded apart inside my shoe. The pain was indescribable. It tasted, in the back of my mouth, like lemons. Above, that train kept on trucking. The conductor probably hadn’t even seen me. Crying a little, or maybe a lot, I called Marty and said, “Can you come get me? My foot was killed in a train accident,” and Marty replied, “Sure thing,” because Marty is cool like that.

So there you go, Pepper, two nuggets of information you’ve been asking for all summer. That wasn’t so hard! I think I’ll continue with this truth telling. It gives me something to pass the time with while you decide if you’re going to wake up.

In the enclosed record, you will find the answers, those secrets I refused to tell you for the sake of my mysterious pride, and even those moments that you were present for but didn’t understand the whole truth of.

You are formally invited to understand everything.

Signed, your inscrutable friend,

Molly P. Mavity

Encl.: the truth (eighty-two pages)

Pepper

World History

Dear Ms. Eldridge,

It has been approximately one week since I first met you in the school cafeteria, and it is only now that I realize that I am owing you a thank-you for your kindness on that day. I was reluctant to talk to you, which I think you’ll find is understandable considering the previous meetings I’ve had with school officials, starting last year when the guidance counselor informed me that I was heading toward not graduating.

“You must be joking,” I said suavely. “All my teachers like me.”

“Do you know what your grades are?” the counselor asked.

“I’m sure they’re not as terrible as you say.”

She proceeded to show me my grades, and it was somewhat like the feeling of viewing the earth very high from a plane, except instead of fields and bodies of water, it was rows and rows of Ds and Fs, and some Cs.

But mostly Ds and Fs.

The counselor pursed her lips. “You can’t get by in this life with just a smile, Ibrahim.”

My forehead wrinkled, both because she called me Ibrahim, which nobody does, and because this was my personal philosophy which she had just shat upon.

There were more meetings after that, about one per academic term, but the credits were not growing much. “Don’t you care, Mr. Al-Yusef?”

“Yes, I care,” I mumbled, but even as I did, I knew that I did not care in the way she meant. Since I first came to America, I saw the way school pummeled the other students. They were stressed to the maximum. I once saw a kid get sick in class because he was so freaked out about a math test. I heard about a girl whose hair fell out when she took too many AP classes. That’s the kind of thing that’s supposed to happen when a person eats too much mercury. This was ridiculous.

“It’s official,” she told me. “You will not graduate. You’ll need to repeat next year.”

I took the news like a champ. I stood proudly, and made a speedy exit into the hallway, where I immediately crouched down and let out a strangled sound. I had to have known this would happen, right? I knew, but I didn’t know, you know?

I carried this heavy feeling inside my chest up until the moment of our meeting last week.

I was in French when I got one of those little pink notes they give kids when they have to go to the office to get yelled at by an adult. I shuffled out of class with my seizure pug, Bertrand, huffing at my side. You remember Bertrand, yes? If not, allow me to remind you of his rotundness, his lolling tongue, and the way he seems always to be wheezing in the back of his throat. Halfway down the hall, Bertrand flopped onto the floor and refused to budge. I was left with no choice but to drag him by his harness the rest of the way, his reflective Mylar vest making an audible whiz across the linoleum, and kids in their classrooms craned their necks to see. Bertrand is forever embarrassing me like this.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved