- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

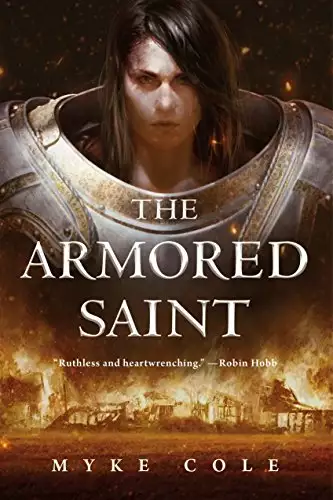

Myke Cole, author of the beloved military fantasy Shadow Ops series, debuts a new epic fantasy trilogy with The Armored Saint, a tale of religious tyrants, arcane war-machines, and underground resistance that will enthrall epic fantasy readers of all ages. After witnessing a horrendous slaughter, young Heloise opposes the Order, and risks bringing their wrath down on herself, her family, and her village. She must confront the true risk that wizards pose to the world, and weigh the safety of her people against justice.

Release date: February 20, 2018

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 192

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Armored Saint

Myke Cole

THEY’LL HEAR YOU

And it shall be as a plague unto your people

From father to son, from mother to daughter, until your seed is dust.

My redemption is the Emperor. My hope is His outstretched hand.

He has made my way plain, and asked only this of me,

Suffer no wizard to live.

—Writ. Ala. I. 14

Heloise took her father’s hand, squeezing it hard. Samson’s eyebrows lifted as he squeezed hers back. “Been a long time since you took your old father’s hand. What happened to you being nearly a woman grown?”

The warm roughness of his palm made her feel safe, but she only smiled up at him, shrugged.

“The road to Hammersdown’s the safest in the valley,” her father said. “No bandit’d risk running into the Order.”

“It’s the Order that scares me.”

“Me, too,” Samson agreed, “but they’re a sight better than a wolf pack or a robber band, eh?”

She didn’t want to hear that something frightened him now. She wanted Samson the father and protector, not Samson the friend. Her father was a big man, and if his hair had gone gray and his stomach drooped over his belt, he more than made up for it with his broad shoulders and thick hands. For all his talk of being frightened, Samson’s eyes were hard, “Serjeant’s eyes,” the village Maior called them. He had fought alongside her father in the Old War. Don’t let his factor’s hands fool you, Heloise. Your father was a shield-hewer, the strongest pikeman I’ve ever known. The very name Samson struck terror into the hearts of the Emperor’s enemies.

“Well.” Samson pulled her into an embrace, holding her tightly to his side as they walked, his arm strong and comforting. “This old man will take what he can get.”

“I love you, Papa…”

“I love you, too, dove.”

Hoofbeats.

Samson stopped, glanced over his shoulder. Heloise turned.

Dust was rising on the road, billowing out behind a column of riders. Too many to be bandits, even if they were brave enough to risk the Order’s main road. Heloise heard jangling chains and looked for a cart, but couldn’t see one.

“Papa, what’s…”

The dust whirled and cleared to reveal Pilgrims, their gray cloaks flapping away from leather armor, flails held out before them. At their head rode a Sojourner. His cloak was edged with gold, the bright red fabric so clean it shone, as if the dust dared not touch him.

The Sojourner held his flail across his chest, head over one shoulder, black iron spikes nestled against the scarlet fabric of his cloak. The red meant he had completed the great Sojourn, a year on the road to visit the sites where the Emperor had fought the devils until they were pushed back into hell. The Pilgrims’ gray marked them as lesser men who’d done only the fortnight-long Pilgrimage. They were pale imitations of their leader, their cloaks simple.

Only their flails were equal: the same stout, well-oiled wood. The same sturdy, black length of chain.

The Order had arrived, as if talk of them had made them appear.

She heard her father gasp in recognition, and then he was yanking her out of the road and into the chill mud. Heloise fell to her knees, winced from the cold wet seeping into her dress. “Eyes down,” Samson said, “mouth closed.”

The terror was as intense as it was sudden.

She obeyed him, closing her mouth and casting her eyes to the ground. The cool air felt suddenly hot, the wide sky pressing down on them.

The hoofbeats came closer, and with them, the sound of the jangling chains.

“Bow your head, girl, now!” Samson hissed.

The hoofbeats seemed to continue endlessly. The sound of the chains rose as they drew closer. Heloise could see the links playing out behind the horses, dragging in the dirt. A dead woman slid past Heloise, green and bloated, caked with road filth. She was wrapped in the long, gray ropes of her innards, tangled in the metal links until Heloise couldn’t tell her guts from the chains. The horses dragged another body beside her, wrapped in metal like a silkworm in molt.

Heloise’s gorge rose at the stink and she gagged, clapping a hand to her mouth. Another moment and they would be past. Please don’t notice us. Please ride on.

The jangling ceased as the riders halted.

Heloise couldn’t resist glancing up. The Sojourner had a narrow face and a smile that was somehow worse than a scowl. He slowly turned his horse, a black animal taller and broader than any Heloise had ever seen. Heloise felt fear climb her spine, followed by anger at him for making her afraid.

“You, there,” the Sojourner called to Samson. “Attend me.”

Samson rose, eyes still on the ground. “Your eminence.”

“You live here?”

“Yes, your eminence. We hail from Lutet, just up the—”

“I know where Lutet is,” the Sojourner said. “What I need to know is where Frogfork is.”

“If you ride on past the Giant’s Shoulder,” Samson said, “you will see a carter’s track through the woods. Take it until the ground goes to marsh, then head into the mire. You’ll see it.”

“Can we make it by nightfall?”

“Yes, my lord. If you ride without stopping.”

“Very well. In that case, have you anything in that satchel to slake my thirst? Maybe some bread? I will pray a cycle for your soul and the Emperor will bless you for supporting His own Hand in the valley.”

“I’m sorry, your eminence. I am a factor on my way to take letters.”

“That is not an answer to my question.”

“All I have is my ledger, pen, and ink.”

“He’s a villager, Holy Father,” one of the Pilgrims said. “They are bred to lie.”

He turned to Samson, held out a hand. “Give it here.”

Without lifting his eyes, Samson handed the satchel over.

The Pilgrim fumbled with the iron buckle before cursing and ripping it open, sending a popped rivet flying. He thrust one gauntleted hand inside and seized a handful of her father’s pens, tossed them into the mud. One of the inkpots followed.

Heloise’s mind whirled, calculating the cost of the precious items, figuring how they could be repaired. It wasn’t so bad. The pens were wood and metal. Some had fine tips, but provided she was careful when she cleaned them, they wouldn’t be damaged. She winced as the inkpot struck the wet mud, but she didn’t think it had cracked. So long as he didn’t throw out any of the …

The Pilgrim’s hand disappeared back into the satchel, emerged with a handful of crumpled paper. Heloise was only able to half-stifle a cry as he tossed the precious sheets in the air. They drifted in the wind, made their way down toward the wet mud.

Before Heloise knew what she was doing, she had taken a long, lunging step, her hand lashing out to grasp at the falling paper. The sudden move stirred the wind, and the precious sheets danced away from her, floating sideways and down, always down, until the ground snatched them up. Heloise chased them, knowing it was useless, unable to stop herself, eyes locked on the slowly spreading stain that was wet mud hungrily devouring the tools of her trade.

A hoof stomped in the mud so close that she had to leap back, her eyes darting up to catch the Pilgrim’s. They were a dazzling gray-blue, like the skim of ice over flowing water. “What in the Emperor’s name do you think you are doing?”

Heloise straightened, panic blossoming in her gut. “Just picking up the … I only meant to pick up the paper before it got wet.”

“Heloise!” Samson said.

“Your eminence,” she added.

“If the paper is on the ground,” the Pilgrim said, “it’s because I meant it to be there.”

Even now, Heloise had to fight not to bend down and pick the paper up. He only threw out some of it, she told herself. It’s not all ruined. The thought helped her to be still.

The Sojourner leaned on his saddle horn, gestured to the bodies in the chains behind them. “See that, girl?”

Heloise glanced back at the bodies. She knew she should answer, but she was robbed of speech, first by fear, then by rage. The Sojourner’s smile slowly faded as he waited.

Samson’s elbow in her ribs. “Answer him!”

“Yes.”

Her father’s elbow in her ribs once more, almost knocking her over. “Your eminence,” Heloise added again.

The Sojourner nodded, whether for the elbowing or at her answer, she couldn’t tell. “Such is the fate of wizards and those who give shelter to wizards. They betrayed the Emperor.”

The Sojourner gestured to the corpses with one red-gloved hand. “This is why the Writ counsels obedience above all, girl. For a chance at power, they would have rent the veil and let the devils walk among us. Is this not more than they deserve?”

Heloise looked sideways at her father, but his eyes were on the ground, his jaw clenched.

Heloise looked back to the corpse. The dead woman’s tongue had swollen out of her mouth, fat and gray. The moment dragged on. The Sojourner had asked her a question, she had to answer.

She pictured herself wrapped in those chains, dragged behind a horse. Her lips moved by themselves. “No, your eminence.”

The Sojourner straightened, satisfied. His small smile returned. “Very well. Brother Tone, I take it there is nothing of use in that rag?”

The Pilgrim looked up from Samson’s satchel. “No, Holy Father. The villager speaks truth, for once.”

“Let’s get moving then. He is likely speaking truth about the ride to Frogfork as well.”

“Yes, Holy Father.” Brother Tone turned his horse, throwing the satchel over his shoulder as he went.

Heloise watched it turn end over end, the lid flapping open, the remaining papers threatening to fall out. She could see the wind plucking at them, ready to cast them down to join their comrades in the ruinous mud. She felt herself start to cry then, because it was the rest of what they had, because she knew that most of their earnings for the next season would have to go to replenish their supply, because …

She heard a dull thud, felt something soft strike her hands.

Her father’s eyes widened and the remains of the Sojourner’s smile vanished.

Heloise looked down at the satchel nestled in her outstretched arms. She had moved. She had caught it. “I’m sorry…” Her lips felt numb. She didn’t know why she’d done it. It was as if her body had been unable to accept the outcome, not when it could do something about it. “I didn’t mean…”

“Perhaps you do not understand what the Holy Writ means by ‘obedience.’” The Sojourner’s voice was cold. His spurs jingled as he touched them to his horse and the animal took a step toward her.

“Please, your eminence.” Samson moved between them. “She’s only a girl.”

Brother Tone twitched the reins and pulled his horse between Samson and the Sojourner.

“She’s near a woman grown,” the Pilgrim said, his blue eyes blazing. “Old enough to know what she’s doing.”

“Please, your eminence,” Samson said, looking up now. “She’s my only child.”

Tone sat up straight, hands tightening on his flail. “Come here. Show me your eye.”

“Holy Brother, there’s no—” Samson began.

“Your. Eye.” The Pilgrim cut him off. “Open it.”

Heloise reached for her father, but he placed a broad hand on her belly, shoving her back. With the other, he reached up to his right eye, prying it wide open with thumb and forefinger.

Tone looked for a long time. At last he sat back, turned to his master, nodded.

“I see no portal,” the Sojourner agreed. “There is no wizardry here, only pride and the foolish love of a father for his child. Your first love should be the Emperor. Above all things.”

“Yes, Holy Brother.” The relief in Samson’s voice made Heloise angry and sad at the same time.

“You’re lucky we’ve pressing business,” the Pilgrim said, tugging his horse back into the column. “Otherwise, I’d teach you a lesson.”

“Yes, Holy Brother,” Samson said again, but it was lost in the pounding of hoofbeats, the jangling of chains, and the rising dust as the riders started moving again. Heloise and Samson stood, silent and frozen, as the whole column trundled into the distance, until at last they turned with the road and moved out of sight.

Samson didn’t take his hand from Heloise until the hoofbeats had faded. Heloise glared after them.

“Bastards,” Samson said, patted the dust from his trousers. Then he turned to Heloise, his face lit with fury. “Idiot girl! What in the Emperor’s name were you thinking?”

Heloise had thought she couldn’t be more frightened, but her father’s hot anger was somehow worse than the Sojourner’s cool threats. “I’m sorry, Papa!” She held out the satchel, showing the dry sheets safe inside. “I saved some…”

Samson’s eyes flicked from her to the satchel and back again. He took a long, shuddering breath and the anger in his eyes vanished as he exhaled. “So you did, girl. So you did.”

He looked at her face and sighed, put his hands on her shoulders. “Heloise, I know you were trying to help, but that was very, very foolish. That could have turned out badly for both of us.”

“I’m sorry, Papa,” she said again, “I don’t know why I did it, I just … but paper is so costly and I thought that … he was finished with it…” The fear and the humiliation swirled in her mind and her gut, so intense that she almost missed a third, stronger emotion, boiling beneath it all.

Rage. Fury at the Order for making her father grovel while they destroyed the tools of his trade.

“No buts,” he cut her off. “That was reckless. When a killer dumps your kit in the mud, you smile sweetly and tell him he’s done right.”

The anger wouldn’t let her. “But he hasn’t done right, Papa. And the Writ says—”

“That a word of truth is more pleasing to the Emperor than poetry, yes. I know the Writ as well as you. But it doesn’t change that however pleasing it may be to the Emperor’s ears, it isn’t to the Sojourner’s, and he’s the one with the flail.”

Heloise’s stomach churned. She had seen dead animals before, and been graveside for funerals more than once. But the image of the dead woman’s face still hung in her mind. Her father was right, she had put him in danger. “I’m sorry, Papa.”

Samson embraced her. “From now on, when the Order’s about, you’re a statue, mind me? Still as a stone. Answer their questions and that’s all. Now, help me clean up this mess.”

They cleaned the mud off the pens as best they could. The inkpot was whole, if a bit dirty. The paper was so thoroughly soaked that it was hard to distinguish from the mud, and they left it where it lay, walking on in silence.

Her father was right. She had risked both of their lives. As Heloise considered it, the anger turned from the Order to herself.

Samson looked at her, smiled grimly. “What’s done is done, Heloise. Don’t drive yourself mad about it.”

“Yes, Papa,” Heloise said, but she could hear the shame in her voice.

Samson put a gentle hand on her shoulder. “What does the Writ tell us about the light of the Sacred Throne?”

“That we bask in its radiance always,” Heloise answered from memory, “that the Emperor’s light warms and blinds in equal measure.”

“That’s so.” Samson nodded. He jerked his thumb up at the sun. “And there it is, shining over us all. No matter what happened, try and take joy in the day, girl. We have precious few of them.”

Heloise did her best, trying to feel the warmth of the sun on her face the rest of the way to Hammersdown, but the sour feeling stayed in her stomach, and her father’s kindness made her feel even worse. She almost wished he’d shout at her, tell her she was a fool who could have gotten them both killed.

She opened her mouth to apologize again when she heard shouts. Growing louder.

“It sounds like Churic,” Heloise said.

Her father nodded. “Something’s got him stirred.”

Churic’s voice grew louder as they walked past Hammersdown’s sentry tower. Heloise heard other voices now, Jaran Trapper, and Bertal Fletcher, too.

Alna Shepherd stood at the common’s far end. His dog, Callie, had rounded the sheep into a tight circle. She stood in front of them, a low growl in her throat, until Alna’s daughter Austre patted the dog into silence.

Jaran stood beside Bertal. The two were practically identical, lined faces nearly hidden behind thick gray beards. Jaran was distinguished only by his gold chain of office, marking him as Maior. Both men were bent over Churic, red-faced and shouting.

Churic was simple, dressed in rags. He’d lived on Hammersdown’s charity his entire life, rocking back and forth on the village green. Heloise’s mother said that Churic’s mother had lustful thoughts so the Emperor had taken Churic’s mind when he was still in the womb. As long as Heloise had known Churic, he’d been as gentle as the sheep Callie protected, but now his face was purple, his words running together until they formed a single long shout, “Nuhnuhnuhnuhnuhnuh.”

“Shut your damn hole!” Jaran shouted back. “Sacred Throne, what’s gotten into you?”

Bertal looked up, saw Samson, and traded a long look with Jaran before putting on a forced smile. “Samson Factor! As I live and breathe. Good to see you!”

Samson let go of Heloise’s hand. She fought the urge to reach for his again.

“We had some trouble on the road,” Samson said. “All’s well here?”

Bertal smiled so broadly, it looked like his cheeks hurt. He glanced nervously at Churic. “Of course all’s well! Why don’t we head to my shop and get to business, eh? Marda’s made some meat pies.” Samson’s eyes stayed on Churic. There was spit on the simpleton’s lips now, white and foaming.

Austre jogged over to them. She was two winters older than Heloise, long black curls framing her face. She had taken a woman’s shape more quickly than Heloise, taller and fuller. Her eyes were dark and beautiful, but they were too wide, her face pale. “Hello, Master Factor. Would Heloise like to come play with Callie until you’re done? Papa’s about to take the flock in and I’ve the afternoon to gather hoxholly. I’ve got my betrothal dress too!” She said to Heloise, “Would you like to see it?”

Samson glanced distractedly at Austre. “Thank you, Austre, but Heloise is here today as my apprentice. She’s to be working as well.”

“Oh,” Austre said. “Well, maybe she can come later?” Heloise was happy to see her, and felt a stab of disappointment at missing the chance to run Callie through the tall grasses on the common, but the pall of fear that hung over the village made it short-lived.

“Look!” Churic jumped to his feet, prying his eye wide. “See the portal? I’m a gateway! Hell comes through me! The devils will soon be here!”

Samson froze. “What did he say?”

“Churic!” Jaran shouted, grabbing Churic’s shoulders. “Shut your damn yob and shut it now!”

But Churic wouldn’t stop. “Wizard! Look! I’m a wizard! I bring hell to you all!”

“What in the shadow of the Throne is this?” Samson’s eyes went hard.

“It’s nothing!” Bertal said. “Mad ravings, is all. You know old Churic.” The fletcher laughed. Heloise thought it sounded more like a scream.

“Hell!” Churic chanted. “Wizard! Devil! The portal in my eye! The portal in my eye!”

“Damn you!” Jaran yelled, hurling Churic to the ground and kneeling on his chest, hands locked around his throat. “You will shut up or by the Emperor I will strangle you and leave you for the wolves.”

“Don’t hurt him!” Heloise started forward, but Samson grabbed her collar, pulling her back.

Churic kicked, gurgling.

“Your girl’s got a kind heart. Nothing wrong with that!” Bertal said. “Anyway, that’s all sorted. Let’s to business.”

“I’ll not do business today,” Samson grunted.

“Papa,” Heloise began, thinking of the paper they’d lost to the mud.

“Samson,” Jaran called to him, loosening his grip so Churic could take a whooping breath. “It’s nothing.”

Samson stabbed an angry finger in the Maior’s direction. “That is not nothing. That is burning talk. I’ll not have dealings anywhere near it.”

“It’s sorted!” Jaran shouted. “We both need the custom. Don’t leave without trade.”

“He said ‘wizardry,’” Samson said. “He said he had the portal in his eye.”

“He’s a madman!” Jaran let Churic draw another breath, tightened his grip again before he could speak.

“Come on.” Austre tugged on Heloise’s hand. “Let’s leave the men to handle this and…”

“It was the Order that troubled us on the road!” Samson shouted, pushing Heloise behind him. “They’re about, might even be close enough to hear! Ask them if they care for the mad!”

“You don’t have to choke him!” Heloise said, struggling, her father’s big hand holding her fast.

“Damn you, Samson!” the Maior shouted. “We both know he’s no wizard! He’s mad!”

“And we both know that doesn’t matter,” Samson replied. “The Order won’t care. They’ll Knit you. And you’re not even a day’s walk from my home and hearth, you bastard. I’ll not have my family Knit because you can’t keep a muzzle on your dog.”

Jaran’s face turned white, red spots showing on his cheeks. “Samson…”

“No more talk. You’d best choke him until he stops kicking,” Heloise’s father seethed, “or cut out his tongue and run him out. For our sake if not your own.”

“He’s simple,” Jaran said. “He’ll die out there.”

“Then that is as the Emperor wills,” Samson snarled. “Better him than mine.”

Samson turned and dragged Heloise so hard that she had to take great, leaping steps to keep up with him. Callie set to barking, a steady, accusing stream that followed them out to the trail home.

Heloise was quiet for a long time, anger at the injustice warring with her fear of the look on her father’s face.

They walked without speaking for as long as Heloise could stand. “Papa, the Maior said he wasn’t a wizard. There was no portal in his eye. The Order would have seen that, even if they came.”

Samson only shook his head, the fury in his eyes fading to sadness.

The look made her bold. “That’s the truth, isn’t it? Churic isn’t a wizard, he’s just simple?”

“Yes.” Samson nodded. “Jaran spoke truth.”

“Then why…” Heloise began.

“Better to Knit than permit,” Samson recited from the Writ. “What happens if Churic really is a wizard and the Order lets it pass?”

“The portal in his eye opens and the devils come through,” Heloise recited from memory. “But he’s not a wizard.”

“Aye”—her father nodded—“but it doesn’t matter. Churic’s life, the lives of all of Hammersdown are nothing against what would be lost should a devil come through the veil. If there’s even the smallest chance that Churic might be telling truth, the Order cannot risk it. Remember this. If you ever hear words of wizardry, loose talk of the veil or what lies beyond, you run straight to me, you hear? Better that we handle it in the village than let it pass to the Order. Remember what you saw on the road today. That is what comes of letting matters like this go unattended.”

She remembered the words of the Writ. This we believe: That the Emperor stood for all mankind during the great battle for the future of the world. That He cast the devils back into hell. That, gravely wounded, He used the last of His life to draw the veil shut between the world and hell, sealing the devils away forever. He died and was reborn as the divine Imperial Soul, immortal, His unblinking eye ever turned on the safety of His empire, on keeping the veil shut.

For a thousand years, humanity had known not peace, but life at least, which was more than they could expect should the devils return.

But sometimes, they did return.

There were men and women who thought themselves above the Imperial Writ, who wanted the wizardry that flowed like water in hell, who were willing to reach beyond the veil to get it. Such people knew great power for a time, but sooner or later, the portal in their eye would open, and they would turn from people into doorways, and the devils would come through.

Suffer no wizard to live.

When a wizard was discovered, the Order came to put the matter right. They took no chances. Even talk of wizarding meant there was a chance the veil had been rent.

And what was rent, must be Knit.

“Will they kill him, Papa?” Heloise asked. “Will they cut out his tongue?”

Samson looked sad. “They will if they are wise, but men are soft when it comes to their own. Churic may be simple, but he is someone’s son, and Jaran would not have kept him through so many winters if there wasn’t at least one in Hammersdown with sympathy for the man.”

“Are the devils so bad? Have you ever seen one?” Heloise asked.

“No one has, poppet. No one but the Order.”

“Then how do we know they’re real?” Heloise asked.

Samson looked annoyed. “Because the Writ tells us, girl. Because the Order reminds us. The devils are real, and they are terrible, and we must be ever vigilant for their return.”

That didn’t make sense, but what Heloise wanted was to feel safe, to feel like she and her father were on the same side, and so all she said was, “Yes, Papa.”

There was a part of Heloise’s stomach that churned and whirled, a sick ball deep in her middle. That part could not forget the dead woman’s face, her swollen tongue gray, and cracked lips. That part told Heloise that even though her father’s words made a cruel kind of sense, this wasn’t the way things were supposed to be.

Copyright © 2018 by Myke Cole

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...