- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

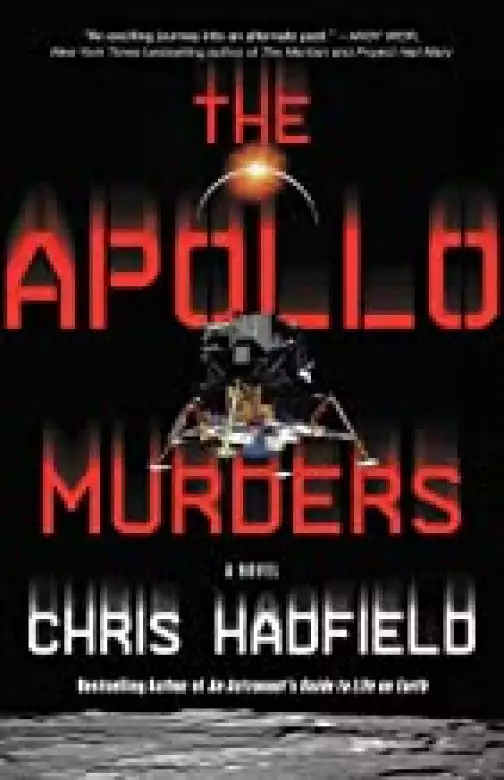

#1 NATIONAL BESTSELLER

The #1 bestselling Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield is back with an exceptional Cold War thriller from the dark heart of the Space Race.

“An exciting journey to an alternate past” Andy Weir, author of The Martian

“Nail-biting” James Cameron, writer and director of Avatar and Titanic

“Not to be missed” Frederick Forsyth, author of The Day of the Jackal

“Explosive” Gregg Hurwitz, author of Orphan X

“Exciting, authentic” Linwood Barclay, author of Find You First

1973. A final, top-secret mission to the Moon. Three astronauts in a tiny module, a quarter of a million miles from home. A quarter of a million miles from help.

As Russian and American crews sprint for a secret bounty hidden away on the lunar surface, old rivalries blossom and the political stakes are stretched to breaking point back on Earth. Houston flight controller Kazimieras "Kaz" Zemeckis must do all he can to keep the NASA crew together, while staying one step ahead of his Soviet rivals. But not everyone on board Apollo 18 is quite who they appear to be.

Full of the fascinating technical detail that fans of The Martian loved, and reminiscent of the thrilling claustrophobia, twists and tension of The Hunt for Red October, The Apollo Murders puts you right there in the moment. Experience the fierce G-forces of launch, the frozen loneliness of Space and the fear of holding on to the outside of a spacecraft orbiting the Earth at 17,000 miles per hour, as told by a former Commander of the International Space Station who has done all of those things in real life.

Strap in and count down for the ride of a lifetime.

Release date: October 12, 2021

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Apollo Murders

Chris Hadfield

PROLOGUE

Chesapeake Bay, 1968

I lost my left eye on a beautiful autumn morning with not a cloud in the sky.

I was flying an F-4 Phantom, a big, heavy jet fighter nicknamed the Double Ugly, with the nose section newly modified to hold reconnaissance cameras. The nose cone was now bulbous, which meant the air flowed differently around it, so I was taking it on a test flight over the Chesapeake Bay to recalibrate the speed sensing system.

I loved flying the Phantom. Pushing forward on the throttles created an instantaneous powerful thrust into my back, and pulling back steadily on the control stick arced the jet’s nose up into the eternal blue. I felt like I was piloting some great winged dinosaur, laughing with effortless grace and freedom in three dimensions.

But today I was staying down close to the water to measure exactly how fast I was going. By comparing what my cockpit dials showed with the readouts from the technicians recording my pass from the shoreline, we could update the airplane’s instruments to tell the truth of the new nose shape.

I pushed the small knob under my left thumb and said into my oxygen mask, “Setting up for the final pass, 550 knots.”

The lead engineer’s voice crackled right back through my helmet’s earpieces. “Roger, Kaz, we’re ready.”

I twisted my head hard to spot the line-up markers, big orange reflective triangles on posts sticking up out of the water. I rolled the Phantom to the left, pulled to turn and align with the proper ground track, and pushed the throttles forward, just short of afterburner, to set speed at 550 knots. Nine miles a minute, or almost 1,000 feet with every tick of my watch’s second hand.

The shoreline trees on my right were a blur as I eased the jet lower over the bay. I needed to cross in front of the measuring cameras at exactly 50 feet above the water. A very quick glance showed my speed at 540 and my altitude at 75, so I added a titch of power and eased the stick forward a hair before leveling off. As the first marker raced up and flicked past under my nose I pushed the button, and said, “Ready.”

“Roger” came back.

As I was about to mark the crossing of the second tower, I saw the seagull.

Just a white-gray speck, but dead ahead. My first instinct was to push forward on the stick so I would miss it, but at 50 feet above the water, that would be a bad idea. My fist and arm muscles clenched, freezing the stick.

The seagull saw what was about to happen and, calling on millions of years of evolved avian instinct, dove to avoid danger, but it was too late. I was moving far faster than any bird.

We hit.

The technicians in the measuring tower were so tightly focused on their sighting equipment they didn’t notice. They briefly wondered why I hadn’t called “Ready” a second time and then “Mark” as I crossed the third tower, but they sat back from their instruments as the lead engineer calmly transmitted, “That’s the last data point, Kaz. Nice flying. See you at the debrief.”

In the cockpit, the explosion was stupendous. The gull hit just ahead and left of me, shattering the acrylic plastic canopy like a grenade. The 550-mile-an-hour wind, full of seagull guts and plexiglas shards, hit my chest and face full force, slamming me back against the ejection seat, then blowing me around in my harness like a ragdoll. I couldn’t see a thing, blindly easing back on the stick to get up and away from the water.

My head was ringing from what felt like a hard punch in my left eye. I blinked fast to try to clear my vision, but I still couldn’t see. As the jet climbed, I pulled the throttles back to midrange to slow down, and leaned forward against my straps to get my face out of the pummeling wind, reaching up with one hand to clear the guck out of my eyes. I wiped hard, left and right, clearing my right eye enough for me to glimpse the horizon. The Phantom was rolling slowly to the right, and still climbing. I moved the control stick to level off, wiped my eyes again, and glanced down at my glove. The light brown leather was soaked in fresh, red blood.

I bet that’s not all from the seagull.

I yanked off the glove to feel around my face, fighting the buffeting wind. My right eye seemed normal, but my numb left cheek felt torn, and I couldn’t see anything out of my left eye, which was now hurting like hell.

My thick green rubber oxygen mask was still in place over my nose and mouth, held there by the heavy jawline clips on my helmet. But my dark green visor was gone, lost somehow in the impact and the wind. I reached back and pivoted my helmet forward, wiggling and recentering it. I needed to talk to somebody, and fast.

“Mayday, Mayday, Mayday!” I yelled, mashing down the comm button with a thumb slippery with blood. “This is Phantom 665. I’ve had a birdstrike. Canopy’s broken.” I couldn’t see well enough to change the radio frequency, and hoped the crew in the observation tower was still listening. The roar in the cockpit was so loud I couldn’t hear any response.

Alternately wiping the blood that kept filling my right eye socket and jamming the heel of my hand hard into my left, I found I could see enough to fly. I looked at the Chesapeake shoreline below me to get my bearings. The mouth of the Potomac was a distinctive shape under my left wing, and I used it to turn towards base, up the Maryland shore to the familiar safety of the runways at Patuxent River Naval Air Station.

The bird had hit the left side of the Phantom, so I knew some of the debris from the collision might have been sucked into that engine, damaging it. I strained to see the instruments—at least I couldn’t see any yellow caution lights. One engine’s enough anyway, I thought, and started to set up for landing.

When I leaned hard to the left, the slipstream blew across my face, keeping the blood from running into my good eye. I shouted again into my mask: “Mayday, Mayday, Mayday, Phantom 665’s lining up for an emergency straight-in full stop, runway 31.” Hoping someone was listening, and that other jets were getting out of my way.

As Pax River neared I pulled my hand away from my left eye and yanked the throttles to idle, to slow enough to drop the landing gear. The airspeed indicator was blurry too, but when I guessed the needle was below 250 knots I grabbed the big red gear knob and slammed it down. The Phantom made the normal clunking and shuddering vibrations as the wheels lowered and locked into place. I reached hard left and slapped the flaps and slats down.

The wind in the cockpit was still my own personal tornado. I kept leaning left, took one last swipe at my right eye to clear the blood, set the throttles about two-thirds back, jammed my palm back into my bleeding left eye socket, and lined up.

The F-4 has small bright lights by the windscreen that glow red when you’re at the right angle for landing, and it also sounds a reassuring steady tone to say you’re on-speed. I blessed the McDonnell Aircraft engineers for their thoughtfulness as I clumsily set up on final. My depth perception was all messed up, so I aimed about a third of the way down the runway and judged the rate of descent as best I could. The ground on either side of the runway came rushing up and slam! I was down, yanking the throttle to idle and pulling up on the handle to release the drag chute, squinting like hell to try to keep the Phantom somewhere near the middle of the runway.

I pulled the stick all the way back into my lap to help air-drag the 17-ton jet to a stop, pushing hard on the wheel brakes, trying to bring the far end of the runway into focus. It looked like it was coming up too fast, so I stood on the brakes, yanking against the leverage of the stick.

And suddenly it was over. The jet lurched to a stop, the engines were at idle, and I saw yellow fire trucks pulling onto the runway, racing towards me. Someone must have heard my radio calls. As the trucks pulled up I swapped hands on my injured eye, reached down to the throttles, raised the finger lifts and shut off both engines.

I leaned back against the ejection seat and closed my good eye. As the adrenaline left my body, excruciating pain took over, a searing fire centered in my left eye socket. The rest of me was numb, nauseous, soaking wet, totally limp.

The fire chief’s ladder rattled against the side of the Phantom. And then I heard his voice next to me.

“Holy Christ,” he said.

1Houston, January 1973

Flat.

Flat, as far as the eye could see.

The plane had just descended below cloud and the hazy, humid South Texas air made the distances look shorter somehow. Kaz leaned forward to get a good look at his new posting. He’d been in the Boeing 727 seat for nearly four hours and his neck cracked as he craned it. Underneath him was a waterway snaking through an industrial maze of petroleum refineries and waterside cranes. His forehead touched the window as he tipped his head to track where it flowed into Galveston Bay, a glistening expanse of oily brown water that fed into the Gulf of Mexico, fuzzily visible on the horizon through the smog.

Not a garden spot.

As the plane descended towards the runway, he noticed each small correction the pilots made, silently evaluating their landing as the tires squawked onto the runway at Houston Intercontinental Airport. Not bad.

The Avis rental car was ready for him. He heaved his overfilled suitcase and satchel into the trunk, and carefully set his guitar on top. “I have too much gear,” he muttered, but Houston was going to be home for a few months, so he’d packed what he figured he’d need.

Kaz glanced at his watch, now on Central time—midday Sunday traffic should be light—and climbed in. As he turned the key, he noticed the name of the model on the key fob. He smiled. They’d rented him a silver Plymouth Satellite.

The accident hadn’t only cost Kaz an eye. Without binocular vision, he’d lost his medical as both a test pilot and an astronaut selectee who’d been assigned to fly on MOL, the military’s planned Manned Orbiting Laboratory spy space station. His work and dreams had disappeared in a bloody flurry of feathers.

The Navy had sent him to postgraduate school to heal and to study space-borne electro-optics, and then used his analysis expertise inside National Security and Central Intelligence. He’d enjoyed the complexity of the work, applying his insight to help shape policy, but had watched with quiet envy as former military pilots flew on Apollo missions and walked on the Moon.

Yet Washington’s ever-changing politics had now brought him here to Houston. President Richard Nixon was feeling the heat in an election year; some districts felt they’d already won the space race, and inflation and unemployment had both been rising. The Department of Defense was on Nixon’s back, with uncertain direction as the Vietnam War was ending, and they were still incensed that he had canceled MOL. The National Reconnaissance Office had assured Nixon that their new Gambit-3 Key Hole satellites could take spy pictures better and more cheaply than astronauts on a space station.

But Nixon was a career politician, and easily found the advantageous middle ground: give the American public one more Moon flight, and let the Department of Defense and its vast budgetary resources pay the cost.

With DoD money behind it, Apollo 18 was redesignated as America’s first all-military spaceflight, and its classified purpose was given to the US Air Force to decide. Given his rare combination of test flying, MOL training and Washington intelligence work, the Navy sent Kaz to Texas to be the crew military liaison.

To keep an eye on things.

As he cruised south on I-45, Kaz was tempted to drive directly to NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center for a look, but instead he headed a bit farther west. Before leaving Washington, he’d made some phone calls and found a place to rent that sounded better than good, near a town called Pearland. He followed the signs towards Galveston, then turned off the big highway at the exit to FM 528.

The land was just as flat as it had seemed from the air, with mud-green cow pasture on both sides of the two-lane road, no gas stations, and no traffic. The sign for his turnoff was so small he almost missed it: Welcome to Polly Ranch Estates.

He followed the unpaved road, his tires crunching on crushed shells. There was a quick rumbling rhythm as the Plymouth crossed a cattle gate set in the road, aligned with a rusted barbed-wire fence strung left and right into the distance. Peering ahead, he saw two lone houses built on small rises in the ground, a pickup truck parked in front of the nearest one. He pulled into the other driveway, glanced in the rear-view mirror to make sure his glass eye was in straight, and opened the door. Stiff, he arched his back as he stood, stretching for a three-count. Too many years sitting on hard ejection seats.

The two houses were new, ranch-style bungalows, but with oddly high, wide garages. Kaz looked left and right—the road was arrow straight for several thousand feet. Perfect.

He headed for the house with the pickup, and as he took the stairs to the front door, it opened. A compact, muscular man in a faded green Ban-Lon golf shirt, blue jeans and pointed brown boots stepped out. Maybe mid-fifties, hair cut close in a graying crew cut, face seaming early with age. Had to be his new landlord, Frank Thompson, who’d said on the phone that he’d been an Avenger pilot in the Pacific theater and was now an airline captain with Continental.

“You Kaz Zemeckis?”

Kaz nodded.

“I’m Frank,” he said, and held out his hand. “Welcome to Polly Ranch! You found us okay?”

Kaz shook the man’s hand. “Yes, thanks. Your directions were good.”

“Hold on a sec,” Frank said and disappeared into his house. He came back out holding up a shiny bronze-colored key, then led the way down the steps and across the new grass between the houses. He unlocked Kaz’s front door, stepped back, and held out the key to Kaz, letting him enter first.

A long, sloping ceiling joining the living room, dining area and kitchen. Saltillo tile floors, lots of windows front and back, dark paneling throughout, and a hallway leading off to the left, presumably to bedrooms. There was still a slight varnish smell in the air. It was fully furnished, perfect for his needs. Kaz liked it, and said so.

“Let’s go have a look at the best room in the house,” Frank said. He walked to the far end of the living room, opened an oversized wooden door and clicked on the lights.

They stepped into a full-sized hangar—50 feet wide, 60 deep, with a 14-foot ceiling. There were garage doors front and back, racks of fluorescent lights above, and a smooth-poured concrete floor. In the middle of it, spotless under the lights, was an orange-and-white, all-metal Cessna 170B, sitting lightly on its cantilever front gear and tailwheel.

“Frank, that’s a beautiful plane. You sure you trust me to fly it?”

“With your background, no question. Want to take it up for a checkout now?”

The only answer to that question was yes.

After Frank pushed a button to open the garage doors, Kaz tucked his rental car into the side of the hangar, and they pushed the Cessna out and down onto the road.

They did a quick walkaround together. Kaz checked the oil, drained a bit of gas into a clear tube to check for water and carefully poured it out on a weed growing by the roadside. They climbed in and Frank talked him through the simple checklist, getting the engine started, watching pressures and temps, checking the controls. Kaz back-taxied to the far end of the road, where it led into a stand of trees. A touch of left brake and extra power and the plane snapped around smartly, lining up with the long, skinny runway.

Kaz checked the mags, and then raised his eyebrows expectantly at Frank, who nodded. Pushing the throttle smoothly all the way to the stop, Kaz checked the gauges, his feet dancing on the rudder pedals, keeping the plane exactly in the middle of the 20-foot-wide pavement. He rocked his head and upper body constantly left and right, so he could see the runway edges on both sides with his good eye. He held the control wheel full forward to raise the tail, then eased it gently back; the 170 lifted off effortlessly at 55 miles per hour. They were flying.

“Where to?” he asked, shouting slightly over the motor noise. Frank waved forward and to the right, and Kaz banked away from the two houses and headed east. He followed FM 528 back across I-45, and saw Galveston Bay for the second time that day, brown on the horizon.

“That’s where you’re going to be working!” Frank shouted, pointing ahead to the left. Kaz glanced through his side window, and for the first time, saw NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center—home of the Apollo program, astronaut training and Mission Control. It was far bigger than he’d expected—hundreds of acres of empty pasture stretching off to the west, and dozens of rectangular white and pale-blue buildings surrounded by parking lots, mostly empty since it was the weekend. In the middle was a long green park, crisscrossed with walking paths joining all the surrounding buildings and dotted with circular ponds.

“Looks like a college campus,” he yelled at Frank.

“They designed it that way so they could give it back to Rice University when the Moon landings ended,” Frank shouted back.

Not so fast, Kaz thought. If he did his job right and Apollo 18 went well, the Air Force might talk Nixon into flying Apollo 19 too.

Kaz pulled the throttle to idle, cut the mixture, and the Cessna’s engine coughed and quit, the wooden propeller suddenly visible in front of them. The click of switches was unnaturally loud as Kaz shut off the electrics.

“Sweet plane, Frank,” he said.

“You fly it better than I do. That’s a skinny runway, and you made it look simple, first try. Glad she’ll be getting some extra use—I’m away too much. Better for the engine.”

Frank showed Kaz where the fuel tank sat against the side of the garage, and they dragged the long hose inside and topped off the wing tanks. There was a clipboard hanging on a hook just inside the door, and Kaz recorded date, flight time and fuel used. They both looked over at the silent plane, sharing an unspoken moment of appreciation for the joy of flight. Since becoming a pilot, Kaz felt he never really understood a place until he’d seen the lay of the land from the air, like a living map below him. It was as if the third dimension added a key piece, building an intuitive sense of proportion in his head.

Frank said, “I’ll leave you to get settled,” and headed back to his place. Kaz lowered the garage door behind him and unloaded the car.

He lugged his heavy suitcase down the L-shaped hallway and set it on the bed in the largest bedroom, pleased to see that it was king-sized. A glance to the left showed a big attached bathroom.

Feeling oddly like he had checked into a hotel, he unzipped the suitcase and started putting things away. He hung up his two suits, one gray, one black, plus a checked sport jacket, in the closet. Did the same with a half-dozen collared shirts, white and light blue, slacks, two ties. One pair of dress shoes, one pair of Adidas. Casual clothes and PT gear went into the lowboy dresser, along with socks and undershorts. Two novels and his traveling alarm clock on the bedside table. Shaving kit and eyeball care bag on the bathroom counter.

The last items in the suitcase were his faded orange US Navy flight suit and leather boots. He touched the black-and-white shoulder patch—the grinning skull and crossbones of the VF-84 Jolly Rogers, from his time flying F-4s off the USS Independence aircraft carrier. Just below it was sewn the much more formal crest of the USN Test Pilot School, where he had graduated top of his class. He rubbed a thumb across the gold of his naval aviator wings—a hard-earned, permanent measure of himself—then lifted the flight suit out, threaded the hanger into the arms, hung it in the closet and tucked his brown lace-up flight boots underneath.

The rattling bedside alarm woke him, his glass eye feeling gritty as he blinked at the sunrise. His first morning on the Texas Gulf Coast.

Kaz rolled out of bed and padded to the bathroom on the stone floor, cold under his bare feet. He relieved himself and then looked in the mirror, assessing what he saw. Six foot, 173 pounds (need to buy a scale), dark chest hair, pale skin. His parents were Lithuanian Jews who had fled the rising threat of Nazi Germany, emigrating to New York when Kaz was an infant. His face was like his dad’s: broad forehead, big ears, a wide jaw leading to a slightly cleft chin. Thick dark eyebrows above pale-blue eyes, one real, one fake. The ocularist had done a nice job of matching the color. He turned his head to the right and leaned closer, pulling down slightly on the skin of his cheek. The scars were there, but mostly faded. After several surgeries (five? six?), the plastic surgeon had rebuilt the eye socket and cheekbone to a near-perfect match.

Good enough for government work.

He methodically went through his morning ritual, five minutes of stretching, sit-ups, back extensions and push-ups, straining his body until his muscles squawked. You get out of it what you put into it.

Feeling looser, he showered and shaved, and brushed his teeth. He rummaged in his eye bag, pulled out a small squeeze bottle and leaned back to put a few artificial tears into his fake eye. He blinked at himself rapidly, his good eye staring back with 20/12 vision.

That impressed them a long time ago during aircrew selection. Eye like a hawk.

2Manned Spacecraft Center

“Houston, we have an electrical problem in the LM.” Apollo Lunar Module Pilot Luke Hemming’s voice was measured, calmly reporting the crisis he was observing.

“Roger, Luke, we’re looking at it.” The Capsule Communicator’s voice, coming from Mission Control in Building 30 at the Manned Spacecraft Center, was equally calm, matching Luke’s dispassionate urgency.

On the instrument panel in front of Luke, the Master Alarm light glowed bright red next to the window, where he couldn’t miss it during their upcoming landing on the Moon. He pushed the red light in to extinguish it, resetting it for subsequent failures. Several multicolored lights were still illuminated on the Caution and Warning panel.

“What are you seeing, Luke?” Mission Commander Tom Hoffman leaned across to have a look, their shoulders touching in the confined cockpit.

“I think it’s a bad voltage sensor,” Luke said. “Volts show zero/off scale low, but amps look good.” Tom peered around him at the gauges, and nodded.

The crew was hot mic, so the CAPCOM heard them. “Roger, Luke, we concur. Continue with Trans-Lunar Coast Activation.”

Tom and Luke carried on bringing the lunar lander to life, taking advantage of what would be the relatively quiet three days after launch, during which they’d travel across the 240,000 miles of space between the Earth and the Moon.

Luke slid his pencil out of his shoulder pocket and made a quick note on the small notepad he’d clipped to the panel. He was tracking the failures as they accumulated; maintaining a running tally was the only way to keep it all straight in his head, especially as multiple systems failed. The Apollo 13 explosion had reinforced just how complicated the spaceship was, and how quickly things could go seriously wrong.

Tom checked his own handwritten list. “So, I see a sticky cabin dump valve, a misconfigured circuit breaker, failed biomed telemetry, and now a bad voltage sensor. I think we’re still GO to continue with the full flight plan. Houston, you concur?”

“Roger, Bulldog, we’ll watch that voltage and likely have some steps for you to take later, but you’re still on track for lunar insertion and landing.” Luke, a Marine Corps captain, had been the one to nickname the tough little spaceship “Bulldog” after the Marine Corps longtime mascot.

Tom and Luke finished the TLC checklist, deactivated the LM, and exited through the tunnel, closing the hatch behind them.

Michael Esdale, in his pilot seat in the Command Module, greeted them with a broad smile. He was the one who would be orbiting the Moon while Tom and Luke went down to the surface. “I’d about given up on you two,” he said. “I made snacks, figuring you might be hungry after all that heavy switch throwing.”

Tom squeezed past Michael into his seat on the left, while Luke settled in on Michael’s right.

“How’s Pursuit doing?” Tom asked.

“Ticking like a Timex,” Michael answered. A US Navy test pilot, Michael had been the one to name the Command Module. As the world’s first Black astronaut, he had decided to honor the WW2 Black fighter pilots, the Tuskegee Airmen, and their unit, the 99th Pursuit Squadron.

“These snacks are…simple,” Luke said, popping a Ritz cracker with a square of cheese on top into his mouth.

“NASA’s version of shit on a shingle,” Michael said. “Maybe some Tang to wash it down?” Despite the TV ads, astronauts hadn’t drunk Tang in space since Gemini in the mid-1960s. One of the early astronauts had vomited Tang during space motion sickness, and reported that it tasted even worse coming back up.

Tom pushed the transmit button. “What next, Houston?”

“Take a fifteen-minute bathroom break while we reset the sim. We’ll pick up again in the Prep for Lunar Orbit Insertion.”

“Sounds good,” Tom replied. He pushed a small knob on his wristwatch and the Apollo 18 crew clambered out of the Command Module simulator.

Kaz, who was watching them on the multiple consoles in the instructor station in the adjoining room, had allowed himself only a moment to think that it might have been him in that sim, prepping for Apollo 18. He’d flown with Luke and Michael, all test pilots together, out of Patuxent River; until the accident, he’d seen them nearly every day, and gone for a beer with them most nights. As he watched the experts create one malfunction after another for the crew to deal with—before the launch, it was crucial that Tom, Luke and Michael see all the possible things that could go wrong and learn how to deal with them—he felt a little rueful that he was about to throw them the biggest mission curve ball ever.

After the bathroom break he saw Michael and Luke head directly back to the sim, but Tom stopped for a quick check-in with the instructors. When he spotted Kaz, he came directly to him, a big smile on his face. “Well look who the cat dragged in! Kazimieras Zemeckis! You’re even uglier than I remember.”

Kaz shook his hand, smiling back. He didn’t know Tom as well as the other two, but they’d been classmates in the same Test Pilot School group at Edwards Air Force Base in California’s Mojave Desert. “Good to see you, Tom,” he said. “You three are doing good work together.”

“Yeah, we’re getting there. These torturers here are making sure of that.”

Kaz said, “I need to talk with you all after the sim.” He paused. “Update from Washington.”

Tom’s forehead furrowed. He didn’t like surprises, especially as the crew commander. He looked at his watch, and then nodded, curtly. “Okay. But time to head back in now. See you at the debrief.”

As Kaz left the sim and walked out of Building 5, he had to stop for a moment to get his bearings. He looked at the parking lot ahead and the nine-story rectangular building on his right, and matched it with what he’d seen while flying over in the Cessna. He turned right across the open central quadrangle and headed towards the Mission Control Center.

From the outside, MCC looked like just another three-story block of stuccoed cement, with windows tinted dark against the Texas sun. He followed the path around to the entrance, where the architect had made a perfunctory effort to give the nation what they expected of their space program—angular concrete forms stuck onto the postmodern Brutalist cubes. Government ugly.

He reached into his sport jacket pocket to retrieve the new NASA ID badge he’d been issued that morning. A guard sitting in front of three heavy silver doors took it from him, checked the building access code and handed it back.

“Welcome to MCC,” he said pleasantly, pushing a button. The clunk was loud as the nearest door unlocked. Like a bank vault, Kaz thought. Let’s see what valuables they’re keeping inside.

The immediate interior was as underwhelming as the exterior. Gray, fluorescent-lit corridors, functional linoleum and fading prints of the Earth and Moon in cheap black frames on the walls. Kaz followed the arrows on the small signs saying MCC. One of the two elevators had an Out of Order sign on it, so he looked around and took the stairs.

He showed his badge to another seated guard, who nodded and pointed with his thumb at the solid-looking door behind him. Kaz gave it a push, and then pushed harder at the unexpected weight. He closed it carefully behind him, trying not to make much noise. He was suddenly inside the hub of manned spaceflight, and the experts were at work.

He’d entered a room of pale-green consoles, each stacked progressively higher, like in a theater. The workstations all faced the three big screens on Kaz’s left, glowing with yellow-orange hieroglyphics of numbers, acronyms and schematics. Behind each console Kaz could see a face, lit up by the displays, hazed by cigarette smoke. Each specialist was wearing a half headset, so they could hear both the radio conversation and the voices around them. Mission emblems of previous spaceflights, all the way back to Gemini 4, hung on the walls.

Kaz stood watching the Flight Control team as they communicated with the Apollo 18 crew, now back at work in Building 5. He spotted a familiar face, a fellow test pilot who raised a hand to wave Kaz over. He threaded his way up the tiered levels, trying not to disturb the concentration of the flight controllers.

Kaz ended up behind the CAPCOM console, where he shook hands with Chad Miller, the backup commander of Apollo 18.

“Welcome to Houston,” Chad said softly. “You were over with the crew?”

Kaz nodded. “They’re doing good.”

The two men watched the room work for a minute. A cartoon-like graphic of Pursuit was projected on the big center screen up front. The ship was about to disappear behind the Moon, so Chad asked, “Need a coffee?” Kaz nodded, and the two quietly worked their way out of the room.

Chad Miller, like the rest of the Apollo 18 prime and backup crewmembers, was a military test pilot. Clear blue eyes, sandy-brown hair, square shoulders filling his short-sleeved sky-blue polo shirt, tucked in smoothly at the narrow waist of his compact body. Gray slacks, brown belt, brown loafers. His strong hands and forearms flexed as he poured coffee into two white-enameled mugs. He wore his oversized Air Force–issued watch on his left wrist.

“Cream or sugar?”

“Black, thanks.”

Chad handed him his cup and led him to a small briefing room, where he and Kaz leaned easily on the long table, catching up. They knew each other somewhat from test pilot days, but Chad had worked at Edwards and Kaz at Patuxent River, so they’d never flown together. Chad had a reputation in the small community as a superb pilot, the consummate stick-and-rudder man, with an unforgiving intolerance of incompetence in himself and others. It was a trait shared by many astronauts, and Kaz respected him for it—someone who could get shit done.

At a pause in conversation, Kaz posed the question that everyone asked the backup crew. “Think you’ll fly?”

“Nah, Tom’s just too damned healthy.” Chad laughed. “And it looks like 18 will be the last Apollo. My last chance to walk on the Moon. I’ve wanted to do that ever since I was a kid.”

Kaz nodded. “I know that feeling. But my days of flying any kind of high-performance machine are done—the Navy prefers a pilot with two eyes.”

“Makes sense, I guess. Hopefully NASA will let you fly backseat T-38 while you’re here.”

Kaz agreed, then leaned to glance out the open door, making sure no one was listening in the hallway.

“You coming to the debrief after the sim?”

Chad nodded.

“There’s something we’ve all got to talk about.” Kaz paused. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...