The Anointed

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

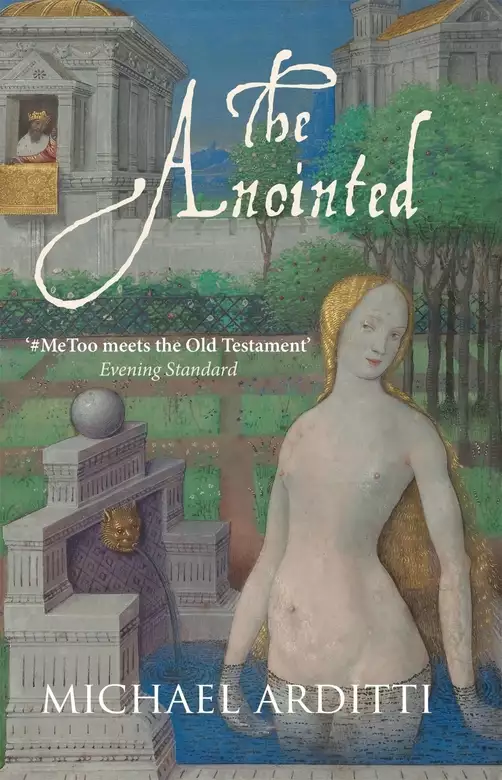

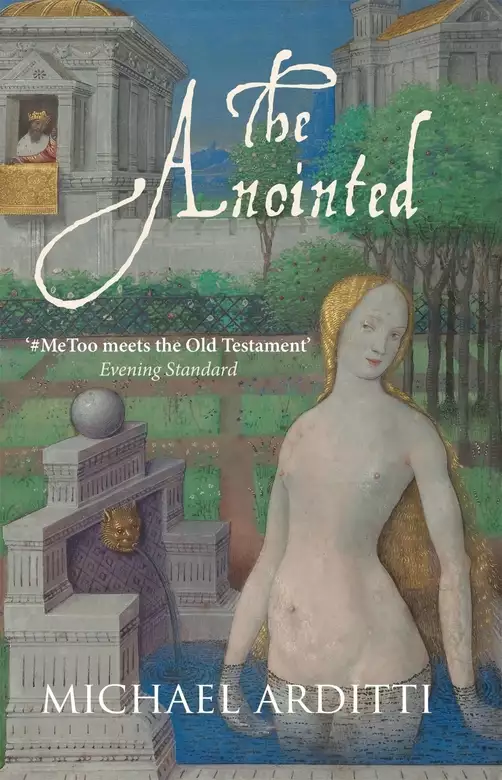

A masterful and subsersive retelling of the Biblical story of David and Bathsheba, by an award-winning novelist at the height of his powers

'[A] fierce, sinewy novel' Howard Jacobsen

'A wonderfully rich novel. Arditti brings Ancient Israel to life' Allan Massie, Scotsman

Michal is a princess, Abigail a wealthy widow, and Bathsheba a soldier's bride, but as women in Ancient Israel their destiny is the same: to obey their fathers, serve their husbands and raise their children.

Marriage to King David seems to offer them an escape, but behind the trappings of power they discover a deeply conflicted man. The legendary hero who slew Goliath, founded Jerusalem and saved Israel is also a vicious despot who murders his rivals, massacres his captives and menaces his harem.

Michael Arditti's masterly new novel centres on three fascinating, formidable women, whose voices have hitherto been silenced. As they tell of love and betrayal, rape and revenge, motherhood and childlessness, they not only present the time-honoured story in a compelling new light but expose a conflict between male ruthlessness and female resistance, which remains strikingly pertinent today.

Release date: May 20, 2021

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 341

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Anointed

Michael Arditti

I ran downstairs, where Mother shook me as if I were the one possessed, before pressing me to her breast and assuring me that in time such spirits grew restless and moved on. But whereas ordinary men could afford to wait, a king had to resume his responsibilities. She did all that she could to hasten the process, wrapping bandages soaked in rose water round his brow and brewing him potions of hyssop, aloes and myrrh. She even sought out one of the sorceresses whom Father had outlawed, promising that, if she restored him to health, she would be free once again to practise her magic, but whether through incompetence or malice she failed. Then, as if to prove that he hadn’t deserted him, the Lord showed a way forward. One morning while he was pacing his chamber, Father heard two Ammonite bondwomen singing a song of home. My brother Jonathan, who was with him, described him standing stock-still, his face relaxing as if he’d taken off a helmet. Jonathan immediately summoned the women and ordered them to repeat their song. At first Father listened calmly, but all at once his mood changed. He leapt up, throwing a footstool at one woman and taking a bite out of her companion's leg. They fled screaming. Jonathan forced them to return, but their agitation was transmitted to Father, and any virtue of their singing was lost.

With the tale of the bondwomen widely reported, Joab, my cousin Abner's armour-bearer, proposed to send for his uncle David, a shepherd of rare musical talent. No sheep-shearing, grape-gathering or New Moon festival in their home town of Bethlehem was complete without his songs. No one, Joab insisted, was better equipped to restore the balance of the king's mind. Abner was dubious that a simple shepherd could succeed where wiser men had failed. Merab and I were dubious of any claim made by such a boorish braggart as Joab. My mother and Jonathan, however, were ready to try anything and, to my relief, their faith was rewarded. David arrived and, according to Jonathan, showed no fear when Father bared his teeth at him. The moment he began to play, the colour returned to Father's cheeks like a sunburst after a storm. This time, moreover, the recovery lasted. After three days, he was deemed to be well enough to greet the household. Abner trimmed his beard, since he was not yet trusted with a razor. Jonathan and the twins bathed him. Mother brought him sweet fragrances and fresh linen. With Merab and our youngest brother, Ishbaal, I was one of the first to be allowed to see him. Sitting straight-backed on his couch and wearing his crown, he beckoned us forward. Merab and I moved to kiss him, but Ishbaal, who at ten was too old for such silliness, shrank back at the door. Jonathan took his hand and led him to Father, who patted his head as if he had returned from routing the Philistines rather than grappling with an evil spirit in a world known only to himself.

I stole a glance across the chamber at the musician, who stood, gaze lowered and clutching his lyre like a shield. To my astonishment, he was a young man, only two or three years older than me, although I brushed aside the comparison. For all the boyish purity of his voice, I had expected any uncle of Joab's to be middle-aged. As soon as we returned downstairs, I resolved to address the anomaly, seeking out Joab in the gatehouse, where he was regaling the guard with his role in David's triumph. He greeted me with a mockingly obsequious bow and asked how he might be of service in a tone that made the offer sound like a threat.

‘I’m here on behalf of my mother,’ I said, careful to conceal my interest. ‘She wants to know more about the man who healed the king.’

‘Ask anyone in Judah,’ he replied pompously. ‘We’re one of the leading clans. David's father, my grandfather Jesse, is the grandson of Boaz, whose father fought alongside Joshua at the battle of Jericho.’

‘Isn’t he too young to be your uncle?’ I asked, sounding as foolish as I felt.

‘We’re a large clan as well as a great one. Virile,’ he added with a grin. ‘David's one of ten. Eight boys and two girls. My mother was the eldest. She was twenty-three when he was born; I was three. As the youngest – and smallest – ‘ Joab said, drawing himself up to his full height, ‘he was baited ruthlessly by his brothers.’

‘And his nephew too, no doubt.’

‘We were children. At six, he was sent to tend the flocks, freeing the others to work in the fields. I could never have endured the long summer days with only sheep for company. We used to joke that he preferred them to people. Though as he grew up, of course, there were compensations.’ His leer lent his words a double meaning, although I couldn’t work out what it was. ‘I mean musical. He could play and sing to his heart's content without people shouting at him to stop.’

How anyone could object to such sublime music baffled me! I felt as deep a loathing for the entire family as for Joab himself. Leaving the gatehouse, I longed to find David to assure him that he wasn’t alone: that there were kindred spirits in the world – in this very house. But although Father allowed me considerable licence to go about Gibeah, among men as well as women, he trusted me not to abuse it. It was one thing to have a private conversation with Joab, a soldier who was pledged to my protection, quite another to address a stranger, especially one so handsome.

It disturbed me to feel such an acute loss for someone I’d barely met. With Father's recovery, I had no chance even to eavesdrop on his playing, spinning fantasies as intricate as his songs. My sole ground for hope was that he hadn’t returned home. As a mark of gratitude, Jonathan had invited David to stay with him and Hodiah. Knowing that Mother would welcome my visit to the sister-in-law she charged me with neglecting, I offered to take her a basket of figs. Pulling my veil across my face, both to pass unnoticed and to escape the dust, I wound my way through the airless streets to the east side of the hill. I was greeted by Menucha, our old nurse, as bent as a willow, who, trusting no one else with her favourite, had accompanied him on his marriage last year. She led me up to the roof where the two men were lying in the sun, their robes removed and tunics loosened. My arrival startled them but, while Jonathan swiftly regained his composure, David continued to look abashed as he fumbled with his belt. He stammered replies to my questions and I was struck that one so eloquent in song should be so reticent in speech. When I praised his music, his face flushed red – although not as red as his hair, which glowed like fire, but a fire so gentle that I could plunge my fingers into it and not be burnt.

Jonathan watched our halting exchange in silence, but when David addressed me as ‘My lady,’ a title that for the first time felt apt, he intervened.

‘My lady? Little Michal? She's not such a lady that she won’t scream for mercy when she's tickled.’ Without warning, he proceeded to prove it. I was outraged. If it had been the twins, who’d teased me since we were children, I might have understood, but Jonathan was the person I loved most in the world. Why should he wish to humiliate me in front of a stranger? Swallowing my tears, I joined in the game, but my pleas and protests were too brittle to fool my brother. Sensing my misery, he became all solicitude, smoothing my robe and calling to Menucha for mulberry juice. But with no sign of Hodiah and no explanation offered for her absence, I declared that I couldn’t stay.

‘Give me a kiss to show that I’m forgiven,’ Jonathan said and took it without waiting for permission. But the kiss that I longed for languished on David's lips.

Jonathan insisted that he stay in Gibeah for the feast to celebrate Father's recovery. As ever, Father opposed any ostentation. This was the man who, on the day of his election as king, had watched in mounting horror as the lot fell first on the tribe of Benjamin and then on the clan of Matri, even hiding among the baggage carts when the choice was narrowed to the family of Kish and, finally, to him. But with rumours of his indisposition circulating widely, he accepted the need to dispel them, not least for fear that the tribes would fail to respond to any future call to arms. He sent invitations to the elders across the land, with one to Samuel, the prophet and judge who had anointed him. Samuel declined, maintaining that he was too old to leave his home in Ramah, which came as a relief to me since his grim features and grizzled beard had cast a pall over my childhood. Moreover, given Father's claim that it was the ever-vindictive prophet who had set the evil spirit on him, his presence would have been an affront. Mother undertook all the preparations, putting Merab and me to work, weaving garlands of rosemary and myrtle to adorn the house. Merab grumbled that there were servants and bondwomen enough for such drudgery, but I was glad of anything that kept me from thinking of David. I didn’t mind thinking of him – quite the reverse – but it hurt to know that he wouldn’t be thinking of me.

As the day dawned, even Merab was excited to wear one of the new chequered robes that Father thought fitting for his virgin daughters (Mother preferred unmarried). At midday we processed to the sanctuary, where a goat, a ram and a bull were sacrificed to the Lord for releasing Father from his torment – I couldn’t help wondering why we didn’t inveigh against his subjecting Father to it in the first place, but I knew better than to say so. The Levites sang, accompanying themselves on cymbals, pipes and horns, but the music, which I’d previously welcomed (not least for drowning out the terrified beasts’ bleats and bellows), sounded crude after David's. If only he had been a Levite and allowed to join them, he could have remained in Gibeah forever. I revelled in the vision until, as if in rebuke, a billow of greasy smoke made me cough.

We returned home to find the feast laid out. Happily, only the elders from Gad and Asher had brought their wives and none had brought their daughters, so I was spared the feigned deference of girls from more exalted tribes, who felt that I’d usurped their position. Now that Samuel had renounced Father, they professed amazement that he had ever endorsed him. At the Festival of Reaping, I even heard one blame the Lord, suggesting that he had been beguiled by Father's height. ‘Saul may look like a king,’ she said, ‘but isn’t the Lord supposed to judge us by what's in our hearts?’ I had promised Mother to ignore such provocation, but the effort was exhausting, so it was a relief to know that for now we were among our own clan, enjoying an easy intimacy that swiftly extended to our guests. Moreover, we shared an amused distaste for the roistering of the men, who sat across the courtyard, shouting, whistling, stamping and clattering bowls.

Midway through the meal, David stood up and moved to the centre of the courtyard. ‘Like a hostage between opposing armies,’ Merab whispered and, while I didn’t care to think of the men as our enemies even in jest, I trembled for David as much as if the image were real. He, however, showed no fear as he sat and tightened the strings of his lyre before starting to play. He sang the old songs of Noah and the Flood, Enoch and the giants, and Jacob and his sons, making much of Benjamin in our honour. He sang new songs in praise of Father, likening his triumphs to those of Joshua and Gideon, and ending with a tribute to Jonathan's singlehanded raid on the Philistines at Micmash, during which Mother looked both distressed and proud and a shadow passed over Father's face – although it might have been the flickering of the fire. Then, when the cheers, from our side as well as the men's, died down, he sang a quiet song professing his faith in the Lord, which was unlike anything I had heard before. He showed no sign of tiring and I could have listened to him all night, but Mother caught my eye and, as if mistrusting its glow, dispatched me to bed.

I couldn’t sleep, and not just because of the sounds that drifted up the stairs. It was more than a year since I had become a woman. But for all the monthly reminders that my body had changed, this was the first time that my heart had acknowledged it. Would I feel the same for every good-looking stranger? If so, how wonderful life was set to be! How enticing! How intense! Even after my restless night, I arose the next morning refreshed, alert and eager to find David. My plan was to congratulate him on his playing and then beg him to teach me. While I discovered music, he would discover Michal. Sitting by my side or, better still, directly behind me, scenting the cassia in my hair, sensing the softness of my fingers as together we plucked the strings, he would surely come to share my feelings. Despite my inexperience (so far I had scarcely even shaken a timbrel), I was confident that my deftness at the loom would translate to the lyre.

So, with another gift of fruit for Hodiah, which, had she not been busy preserving the leftovers from the feast, might have aroused Mother's suspicions, I made my way to Jonathan's house. I found Hodiah in the courtyard kneading dough, and, after the usual empty courtesies, which made me want to scream, I asked after David. To my dismay, she revealed that he’d returned home, travelling through the night to avoid the heat. For once she looked almost happy, and I felt an overwhelming urge to slap the fatuous smile from her face. My rage was so fierce that I feared that the evil spirit, having abandoned Father, had taken hold of me. I felt lost and bereft and sick and helpless. What made it worse was that, although he had come to mean as much to me as anyone in my family (with all the guilt that entailed), I knew that I was nothing to him but a silly girl who’d giggled and screamed when her brother tickled her. And, while I hated him for that indignity, Jonathan was the only person I could talk to about David without sounding false. When he finally came downstairs, eyes puffed and cheeks blotchy, dismissing Hodiah's proffered bowl of porridge with unwonted gruffness, I broached the subject, treading as carefully as a child on the edge of a well.

‘Why has the musician gone home?’

‘Father is himself again, thank the Lord.’

‘But it's too soon. What if he has another attack?’

‘We can send for David. Bethlehem's only a day's ride away. We gave him one of our best donkeys.’

In desperation, I pictured myself as a sorceress with the power to conjure evil spirits and so require David's recall. Then I remembered Father gibbering in the corner and blushed for shame.

Jonathan explained that, after his recovery, Father wanted no reminder of his affliction. As the first king of Israel, he felt a twofold obligation, to prove not only his own worth but that of the crown itself. The people's demand for a king had been contentious. Weary of warfare and the foreign armies garrisoned along their borders, they looked to other nations whose inhabitants tended their crops and their flocks and their children in peace. They wanted a ruler who would unite the factious tribes and drive out the invaders. Samuel, then the country's effective leader, objected. He denounced the call to be like other nations since, by a unique covenant, the Lord our God was also our king. He warned that he was a jealous God who would not brook an earthly rival. In the event, Samuel was the jealous one. Whereas the Lord acceded to the people's demand, he never accepted it. He presided over Father's election but lost no opportunity to take him to task, finally breaking with him on the slenderest pretext, which, even if he had not summoned the evil spirit, had left Father prone to its attack.

News of that attack reached the Philistines. In the two years since their defeat at Micmash, they had kept to their coastal strongholds and, a few border raids apart, made no further incursions into our territory. Now, seeking to exploit Father's weakness, they marched into Judah, threatening to split the country in two. With his cousin Abner as his second-in-command, Father marshalled his troops and prepared to meet the enemy in the valley of Elah. This time he was accompanied by all three of my older brothers. Jonathan was already a seasoned soldier, but the twins, having just turned eighteen, were to fight their first campaign. Mother, too anxious even to watch them exercise, secured Abner's sacred oath to keep them from the thick of battle. Seeing them set off with faces as bright as their armour, I almost forgave them their taunts and prayed as ardently as Mother for their safe return. Ishbaal remained at home, puffed up by Father's parting words that he must be the man of the house, until his demand to take his meals separately from the ‘females’ earned him a rebuke from Mother and a ringing slap from Merab.

We didn’t expect to endure his insolence for long. None of Father's recent campaigns had lasted more than a week. Even for one with my meagre interest in warfare, the pattern was predictable. The Philistines advanced; we rebuffed them; they retreated to their five unassailable cities. This time, however, things were different. Ten days passed without word from the field. Mother, fearing the worst, took regular peace offerings to the sanctuary. Finally, a messenger arrived for Ahitophel, Father's chief adviser, bringing news that the battle had been won – without one Israelite casualty. After days of deadlock when a monstrous Philistine champion goaded our forces, a young Judahite shepherd confronted him with nothing but a sling. He felled him with a single stone, whereupon their entire army took flight.

‘A11 praise to the Lord,’ Mother said. But, even with the Lord's help, the victory was awe-inspiring, not least when the messenger swore that the Philistine was six and a half cubits tall. Moreover, his mention of the Judahite shepherd unsettled me. I told myself not to be fanciful: there were hundreds of shepherds in the hill country. Yet what were the chances of two from the same tribe coming to our aid within a year? I longed to ask the messenger to describe the youth more fully – starting with the colour of his hair – but I couldn’t risk rousing Mother's and Merab's suspicions. Besides, what would it prove? Red hair might well be a Judahite trait. Such coincidences occurred daily; which was why there was a word for them. It would be wrong to let my regard for one Judahite shepherd blind me to the merits of the rest.

I turned back to the messenger, who was explaining that the Benjaminite troops would reach Gibeah in a matter of hours. With no time to spare, we went our separate ways: Mother to take a thanksgiving offering to the sanctuary; Ahitophel to proclaim the victory to the people; Merab and I to instruct the servants. Once preparations were in hand, I bathed, put on my chequered robe (now pleasingly tight around the chest), and joined Mother, Merab and Hodiah at the city gate. We stood in the dusty heat, while the women and children sang and danced, played pipes and shook timbrels, until a shout from the watchtower heralded the army's approach. At first I recognised only Father, or rather his mule, its white coat gleaming in the sun, but, as they drew nearer, I made out Abner, with Joab bearing his shield; the twins, riding with a newfound swagger; and, finally, Jonathan, side by side with a man whom I’d never expected to meet again, let alone as the nation's saviour. His prominence in the procession left no doubt that the valiant shepherd was David.

Breathless, I watched the men dismount. The twins, forgetting that they were battle-scarred veterans, ran forward to hug Mother before recollecting themselves with lofty waves at Merab and me. The others greeted us warmly, except for Father, who gave us each a perfunctory kiss, and barely acknowledging the chants of ‘Saul’, headed straight to the house. Sensing the crowd's disappointment, Jonathan dragged a diffident David towards them and, without a word (which would in any case have been drowned by the cheers), clasped his hand in a victory salute, confirming even to those yet to hear the story that this was the hero of the hour. With his arm draped like a garland around David's neck, he presented him to us: first to Mother, who commended his courage, marvelling at his coupling of martial and musical skill; then to Hodiah, who echoed her sentiments, although, as she addressed David, her eyes strayed to Jonathan, her yearning to kiss him as palpable as her fear of a rebuff. Merab added her plaudits, while wrinkling her nose at the battlefield smell and bloodstains on David's tunic. At last it was my turn but, despite the sparkling speech on the tip of my tongue, I was struck as dumb as the serpent in Eden.

‘Come on little sister, is this how you greet your country's champion?’ Jonathan asked. All I could do was shake my head like a goose.

‘Count yourself lucky,’ Ishbaal interjected. ‘She usually won’t stop talking.’

Jonathan, indulgent even to Ishbaal, broke away from David, grabbed his impudent young brother and, feigning fury, wrestled him to the ground, releasing him unharmed to the regret of everyone except Mother. Deploring the impropriety, she sent Jonathan and David home to wash and rest before returning to eat with Father. Watching them go, I was surprised to see Jonathan lay his hand on David's shoulder as if to steer him through unfamiliar streets. Hodiah followed eagerly, but neither man looked round.

I blinked back the tears that unaccountably welled in my eyes and returned home. Struggling to make sense of both David's prodigious talents and his strange reappearance in our lives, I hoped for an explanation when Jonathan paid his usual visit to Merab's and my chamber before the meal. David hadn’t joined him, although whether he considered that, as girls, we were beneath his notice or, as princesses, we were above his station, I couldn’t say. Too wary of Jonathan's ridicule to ask, I urged him instead to tell us the story of the battle.

‘It's really the story of David,’ he said. And although it was another man's triumph, I had never seen my brother look happier. Ignoring her protests, he flung himself on Merab's bed and began. ‘The Philistines were camped across the valley, close enough for us to hear them carousing at night and drilling in the morning, the clash of their swords a stark reminder that their weapons were iron and ours were only wood and bone. Neither side dared risk an attack. Without a priest to cast the sacred stones and determine the Lord's will, Father concentrated on securing our position. He seemed in command – of himself, I mean – but he’d lost the confidence that inspired us to victory over the Amalekites. Then, without warning, a man advanced from the Philistine tents. But what a man! I swear he was more than four cubits tall – ‘

‘Not six?’ Merab interjected.

‘Are you mad? That's already a good hand taller than Father. He was magnificent. His armour gleamed. The purple plumes in his helmet rippled in the breeze. I was so dazzled that, for a moment, I forgot he was the enemy. Then he spoke, in a voice as deep as the valley itself.’

‘And I’m the one who's mad!’

‘I swear it,’ Jonathan said, adopting a voice that might have been menacing had it not recalled the Nephilim giants with whom he’d peopled my childhood. ‘“Saul, Saul, why are you hiding up there on the hillside? Come down – “ Oh, this is torture!’ He resumed in his own voice. “‘Come down and fight, Saul! Just you and me, man to man. Whoever wins, his side can claim victory. Fight in the name of your god! Or are you ashamed of the god you’re not allowed to name?” Then he named him – repeatedly, mockingly, impiously – and Father bore it, grim-faced. We waited for him to accept the challenge. He's never shrunk from one before. He may be nearly fifty but he can crush an opponent half his age – me, for instance, during practice. But he hung back, as though the Philistine's mockery had unmanned him. Both Abner and I begged him to let us fight in his place, but he flatly refused. He was sure we’d be killed and the troops would lose heart and desert.’

‘So what changed?’ I asked, aching for David's arrival in the field.

‘Nothing, for six whole days. Our forces marked time while the Philistine strutted and jeered. I warned Father that the men would be far more disheartened if no one took up the challenge than if one of us did and fell, but he wouldn’t listen. It was as though the evil spirit still had a hold on him, making him doubt himself, his son, and even the Lord.’

‘But what about David?’ I asked, as insistently as I dared. ‘Did you call him back to play for Father?’

‘No need. He’d been sent with provisions for his three older brothers, who were among the Judahite contingent. By chance – that's to say, providence – he heard the Philistine's challenge and made up his mind to accept it.’

‘But he's so small,’ Merab said.

‘Not tall, I grant,’ Jonathan replied curtly. ‘Which makes his success all the more remarkable. Joab brought him again to Abner – ‘

‘I notice Joab didn’t come forward himself,’ I said.

‘Fair's fair,’ Jonathan replied, ‘no one did. They were all too aware of Father's misgivings. But David was new to the camp. He entered our tent and, before he’d even spoken, it was as if a lamp had been lit.’

‘You sound like one of his songs,’ Merab said.

‘Ignore her!’ I said. ‘What happened next?’

‘I was astonished to see him, but still more astonished by Father, who showed no sign of recognising him. I worried that the evil spirit had lodged in his mind. Then I realised that for Father to acknowledge him would be to acknowledge his own infirmity. So I followed his lead. For his part, David took no offence, as though he’d never presume that a king or prince would remember him.’

‘Unless he was also dissembling,’ Merab said.

‘You don’t know him; he's far too modest, something you may find it hard to appreciate.’

‘Stop interrupting!’ I said to Merab. ‘So what did David do next?’

‘Begged Father to let him accept the challenge. When Father asked him if he wanted to die, he swore that he’d braved greater dangers guarding his sheep: killing marauding lions and bears with his bare hands.’

‘Did you believe it?’ I asked, over Merab's snort.

‘I believed that he believed it,’ he replied evasively. ‘In the end, Father granted his request. I suspect that he thought him expendable.’ I coughed to conceal a groan, as Jonathan stared at me in bemusement. ‘There was a remote chance he’d succeed and, if he failed, the contest would have been too unequal to damage morale. He even offered him his armour, which was a nonsense, since it would have dwarfed me! Still, David insisted on trying it on.’

‘More dissembling?’ Merab asked.

‘Why must you be so spiteful? As it turned out, he wore no armour of any sort and took no weapons except for a stick, a sling and a bag of stones. When he saw him, the Philistine was incensed, railing at our disrespect and threatening retribution. He pounded the ground, rocking from side to side, so blinded with rage that for the first time I thought that David might have a chance. He bellowed that he’d eat his flesh raw, which chilled me, but David was undaunted. I couldn’t see his face, but I saw the contraction of his shoulders as he calmly appraised his target, took aim and hit him straight between the eyes. The Philistine stood stupefied, before toppling forward, less man than tree. A thunderous cheer rose up from our ranks while the enemy fell deathly silent. Then David surprised me again. No longer the noble warrior, he snatched the Philistine's sword and hacked at his neck until it snapped. He held the head aloft, letting blood drip over himself like rain.’

‘Why the surprise?’ Merab asked. ‘Red-haired men are born to shed blood.’

‘Then be grateful. If it weren’t for him, the blood that was shed would have been ours. When they saw their fallen champion, the Philistines fled. Our men pursued them, slaughtering and plundering all the way to Gath and Ekron.’

‘I am grateful,’ Merab said. ‘But you make too much of it. One well-aimed shot can’t compare with all Father's campaigns or even your valour at Micmash.’

‘It's a well-aimed shot that might win him a king's daughter.’

‘. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...