The Savage History of Proofrock, Idaho opens looking through the two eyeholes of a mask, and of course there’s some heavy, menacing breathing.

What those eyeholes are fixed on from behind the bushes is a ten-year-old kid. It’s nighttime, well after midnight, and the kid’s sitting in a barely moving swing at Founders Park. It’s where the old staging area for Terra Nova used to be, eight years ago.

The kid’s head is down so his face is hidden. He could be dead, posed there, his hands wired to the swing’s galvanized chains, but then a thin breath comes up white and frosted, and he starts to look up, eyes first.

Before his face comes into focus, The Savage History of Proofrock, Idaho cuts to an occluded angle into . . . a shed?

It is. A dark workshop of some sort, like a room you scream through at a haunted house down in Idaho Falls.

No more mask to look through. Just a nervous space between two boards of the wall.

Words sizzle into the bottom of the screen and then flame away: the Chainsaw’s been Dead for Years. The irregular capitalization is supposed to make it scarier, like a ransom note.

In this shed, on this grimy workbench, a man in a leather apron is working on this chainsaw. This man’s got a bit of size—linebacker shoulders, veins cresting on his forearms. His hands are white and tan, and the camera stays on them, documenting his every ministration on this chainsaw.

It’s dark, the angle’s bad and unsteady, but that only makes it better, really.

“Is that Slipknot?” Paul says about the music thumping in this shed.

Hettie shushes him, says, “He’s old, okay?”

He’s old and he’s taking the top cover off the chainsaw, or trying to. Eventually he figures out to push the chain brake—the cover comes right off. It’s enough of a surprise that the cover goes clattering onto the floor, almost loudly enough to cover the squeaky yelp that’s much closer to the camera.

Almost loud enough to cover that, but not quite.

Instead of a nightmare face stooping down into frame after this runaway chainsaw cover, there’s twelve seconds of listening silence after the song’s turned off. The man’s hands are still on the workbench, the fingertips to the dirty wood, the palms high and arched away so it’s like there’s two pale spiders doing that thing spiders do when their eight eyes and their leg bristles have told them

there’s a presence in the room.

And then that grimy leather apron is rushing to this camera, blacking the screen out.

Paul chuckles, draws deep on the joint and holds it, holds it, then leans forward to breathe that smoke into Hettie’s mouth like she used to like, when they were fourteen.

“You’re going to secondhand kill me,” she says with a satisfied cough, holding the videocamera high and wide, out of this.

“Only after I first-hand do something else . . . ” Paul says back, his hand rasping up the denim of her thigh.

“But did it scare you?” Hettie asks, keeping his hand in check and shaking the camera so Paul’s syrupy-thinking self can know what she’s talking about: the documentary.

She pinches the joint away from him for her own toke, and doesn’t cough it out.

Where they’re sitting is the doorway alcove of the library on Main Street, right under the book deposit slot. Out past their knees, Proofrock’s dead. Someone just needs to bury it.

“Your mom know you snuck Jan out after dark?” Paul asks, squinting against Hettie’s exhale.

“She’s more worried about who my dad’s dating this week,” Hettie says from the depths of her own syrup bottle. “Janny Boy’s a good little actor, though, isn’t he? I told him to pretend he was a ghost, just sitting there.”

“What’d you do with the snow?” Paul asks, his eyes practically bleeding.

It’s nearly halfway through October, now. The snow they always get by Halloween hasn’t come yet, but there’s been plenty of small ones, trying to add up into the real deal.

“I edited it out,” Hettie says, sneaking a look up to Paul to see if he’ll buy this, but his stoned mind is still assembling her words into a sentence. Hettie shoulders into his chest, says, “We shot it in July, idiot.”

“But his breath,” Paul manages to cobble together, doing his fingers to slow-motion the puff of white Jan had breathed out that night.

“I didn’t give him a cigarette, if that’s what you’re asking.”

“So he’s really a ghost, what?”

“Confectioner’s sugar.”

“In his mouth?” Paul asks.

Hettie shrugs, says, obviously, “He loved it.”

“Ghosts and swings and baking goods,” Paul says, hauling the camera up to his shoulder, aiming it at Hettie. “Tell us, Herr Director, why do little ghost boys with sweet white mouths like to frequent parks after dark?”

“Because it looks good for my senior project,” Hettie says, cupping the lens in her palm, guiding the camera down.

It would be easier to shoot this documentary with her phone, which is much better for low-light situations, but this is throwback. Her dad’s VHS camera was still in the attic, along with everything else he’d left when he bailed, but Hettie’s paying for these blank tapes herself, “to show she’s committed,” that “this isn’t just another passing thing.”

What it is is her ticket out of here.

The world will roll out the red carpet for footage like this, from the heart of the murder capital of America. First there was Camp Blood half a century and more ago, then there was the Independence Day Massacre when she was in fourth grade, and then, for junior high, there was Dark Mill South’s Reunion Tour. Nearly forty dead in a town of three thousand is a per capita nightmare, even across a few years.

And that translates to serious bucks.

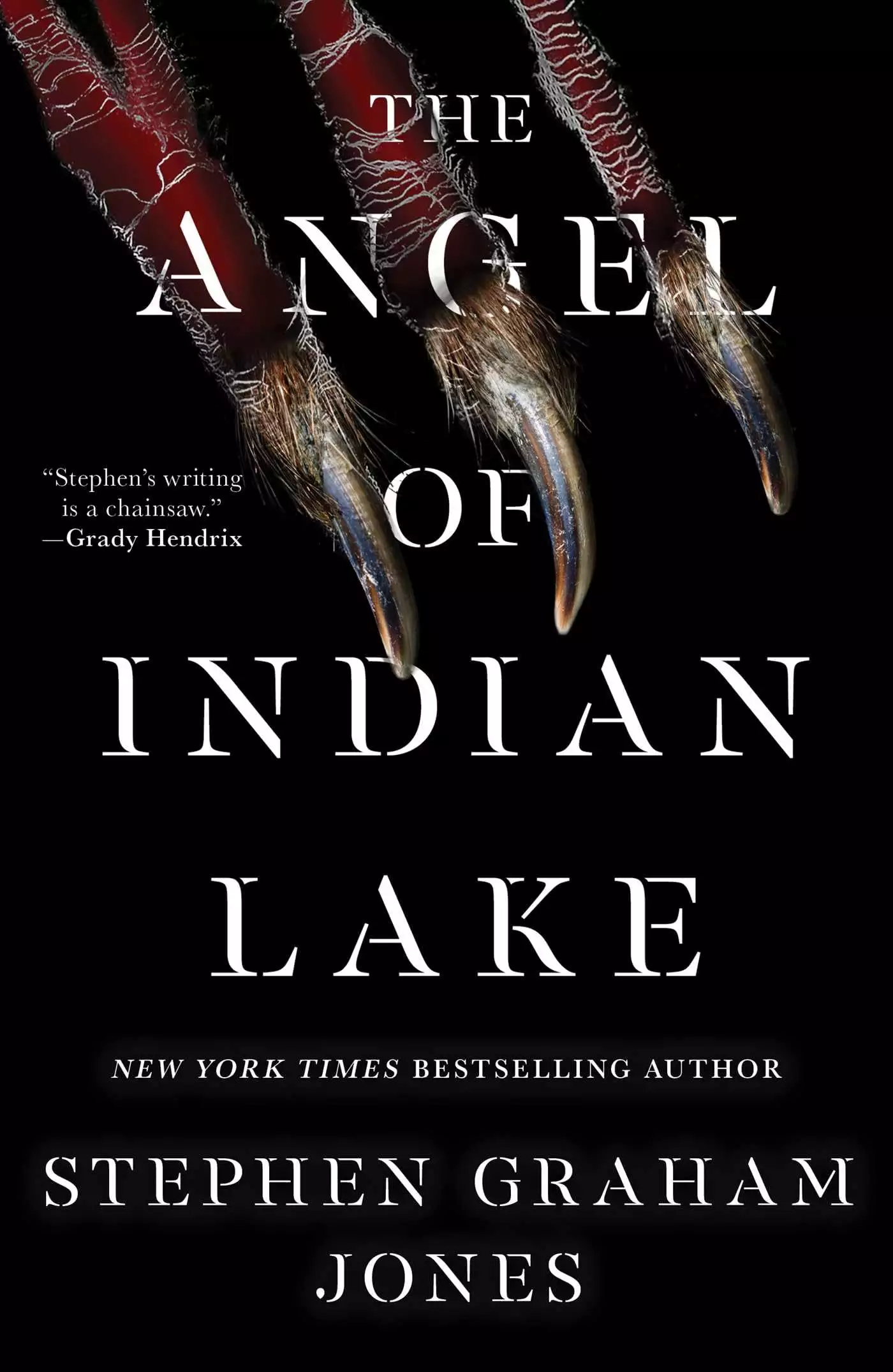

Now if she can only get this Angel of Indian Lake’s tattered white nightgown and J-horror hair and supposedly bare feet on tape tonight, blurry and distant, “ethereal and timeless,” then . . . then everything, right? The doors to the future open up for Hettie Jansson, and she walks through with a Joan Jett scowl, squinting from the sea of flashbulbs but not ever wanting them to stop, either.

The problem, though, it’s that the Angel isn’t reliable, is probably just some practical joke the jocks have kept going all the way since summer. Joke or not, though, she’s the missing ingredient for The Savage History of Proofrock, Idaho, the piece that sends it into the horror stratosphere. And they’ve got all night to fit her into a viewfinder, hit record, and hold steady fifty-nine and a half seconds—it’s how long that famous Bigfoot recording is, right? ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved