People were hanged for less.

Peter Glienke stomped along the field path toward the shore, flicking a willow switch back and forth with jerky movements, swiping at the tops of thistles and nettles on the edges of the path. Whack. Hanged for less. Whack. Just for looking at someone the wrong way. Whack. For failing to take off one’s hat in respect. Whack. With angry fascination, Peter began to recite to himself all the horrible things done to people for the most insignificant of offenses. Hanged on the gallows. Whack. Head cut off. Whack. Drawn and quartered. Whack. Tossed into a rat-infested jail. Spread-eagled. Run through with a sword. Whack, whack, whack.

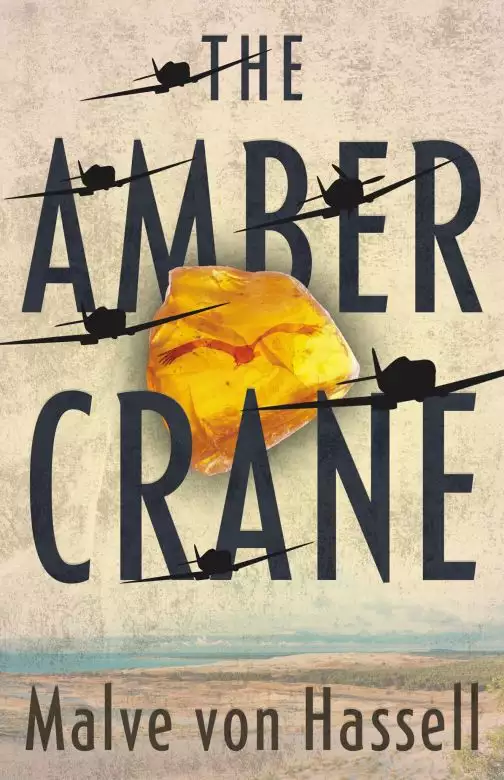

Stealing. Murder. Pillage. Destruction. Peter could understand punishment for those crimes. But walking on the beach? Picking up a piece of amber, something nature spit onto the sand after a storm?

A hoarse rattling sound made him look up. A flock of cranes was taking off into the sky. They were free, he thought. If only they did not screech so much. Usually, he liked cranes. At least they did not fly in regimented formation like silly geese without a mind of their own, but rather in a raggedy shifting V spilling across the sky like droplets of ink. One still sat in a clump of grass, apparently undecided whether to take off after his mates. That young crane was like him, stuck, unable to move.

Stupid birds. They were ungainly, with a tail and beak too short for its elongated shape. Yet, when Peter gazed at the glowing evening sky, he could not help but be bewitched by their wildness, silhouetted against the light, flying with high-pitched whistling and loud rattling calls, without any discernible pattern.

In the distance, on an elevated stretch along the shoreline, he could make out the gallows, dark and threatening in the dusk, a rough-hewn pole with a crossbar. In his lifetime, no one had been executed there, but still the sight made Peter uncomfortable. He averted his eyes and focused on the silvery tips of the churning sea below.

Something urged him on. He wanted to get closer to the water. After a moment’s hesitation, he scrambled down, leaving the path behind. Once on the beach, he continued along the shoreline, relishing the bracing smell of the sea and the spray of the incoming waves. But his sense of pleasure did not last long. He could not keep from thinking about all the things that had been going wrong lately.

Until last year, he had been content and satisfied with his life.

Of course, war continued to rage across his homeland—as it had done since long before his birth fifteen years ago. But now, in 1644, the twenty-seventh year of the war, Peter could not imagine life in any other way. He cared little whether the Swedes or the Imperialists were in control. It made no difference to the horrors and arbitrary punishments they inflicted on the populace. They simply took turns pushing and shoving their way into town and devastating fields and villages all around. In their wake, sad throngs of people shuffled along dusty roads in search of food and shelter.

People bit their lips and shook their heads when yet another one of the sons of Stolpmünde died on a distant battlefield. They turned away when refugees with grey, weary faces traveled through the town, walking silently, their feet wrapped in rags. They shrugged when fields lay fallow because there were not enough people left alive to plant them. That was life, the citizens said. There is nothing we can do. Maybe the war will end one day, but we have to take care of our own, they said, sighing and going on with the business of the day.

Peter did the same, shrugging and turning away from what he could not change. Together with his friends, he skipped stones at bends of the Stolpe and stole pasties from stalls on market days. He dared others to run along the forbidden beach and made jokes about girls, pretending not to be interested. He paid little attention to his sister, tugging on her braids and cuffing her affectionately before forgetting about her. He rarely gave any thought to the fact that Effie was frail and inexplicably locked in silence and jerky movements as if her body was a cage. His parents would take care of her.

Peter was content in his apprenticeship. He loved amber. He loved the translucence of polished pieces, soft to the touch, yet solid and firm, and the colors, ranging from tawny gold to dark reds and rusty browns. He loved the feel of the tools in his hand and the scent of resin permeating the workshop.

However, last year, Peter’s brother Lorenz, a soldier in the Swedish army, lost his life, and everything changed. Peter’s mother died shortly after that, and his father spent most of his waking hours in his study. Effie spent most of her time in her room. The only sounds relieving the silence hanging over the house came from the kitchen where Clare banged pots and sometimes hummed as she worked. Peter began to avoid going home. Master Nowak’s house had become a place of refuge, warm and welcoming. And yet, there as well Peter felt stifled and restless, chafing under the rules and regulations imposed by the guild, and impatient to be done with his apprenticeship.

With a frustrated sigh, Peter tugged on his jerkin. It was too tight around his neck. He would have to ask his father for money to buy a new one. Gloomily he kept an eye on the foamy surf close to his feet as he continued along the shore and thought about the humiliating afternoon in the workshop.

“Well, you will have to rework that on Monday,” Master Nowak had said. “See the crack?” His face stern, he twisted the small piece of amber in his hand. It was supposed to become the mouthpiece of a pipe. “You forgot to place it in water before heating it. You have been an apprentice for almost three years now. I should not have to tell you something that basic.”

Peter opened his mouth to protest that he had too many other tasks that day to concentrate, but he stopped himself. Master Nowak was right after all. Scowling, Peter gathered his tools and cleaned up his workstation before setting out for his father’s house.

Master Nowak’s house was at the southern edge of the harbor town Stolpmünde, while Peter’s family lived northeast of the harbor. Peter did not mind the long walk. It gave him time to think.

Absorbed in his thoughts, Peter walked with his head bent, picking his way past refuse and ruts in the street. He was oblivious to the familiar sight of timber-frame buildings with sagging windows and walls blackened by fire. After all his mistakes, Master Nowak would never let him take the exam. He did not even allow Peter to accompany him to the amber market in Königsberg in the summer. Peter had pleaded with him, but the answer remained the same. “It is not a good time,” Master Nowak had said. There never would be a good time; the war would go on forever.

When he crossed the central square, he glanced at the row of stately patrician houses. Marthe Neuhof, the mayor’s daughter, lived in the one with the grey-green façade. This portion of the town had escaped the ravages of the war. Both Swedish and Imperial Army officers liked to be quartered there and made sure those houses were protected. Hunching his shoulders, Peter continued on his way. Marthe would never even notice him anyway. He walked past the familiar red brick church and storage buildings along the harbor, and crossed the river to the northeastern side of the town.

At the turnoff toward his parents’ home at the edge of the town, Peter looked back to see whether anyone was watching. Then, with an angry toss of his head, he headed toward the shore. He did not have a beach permit, but he was tired of all the rules and regulations. What did he care about a distant duke’s claim to all the amber along the Baltic Sea? This was his town, his home, his beach.

When Peter was younger, he and his friends had sometimes dared each other to sneak into the dunes, pretending to search for amber and being chased by the beach watchman, thrilled by the danger of being caught.

“Do not ever pick up amber and think you can keep it,” Master Nowak told him when Peter started his apprenticeship. “All amber must be surrendered to the guild. They have not hung anybody for stealing amber for some time, but still, the punishment is severe. You could be thrown into the town jail or expelled from the city. Besides, whatever you do reflects on my position in the guild.”

“Why do we have to put up with the guild?”

“The restrictions are imposed by the Duke of Prussia, and the guild administers them,” Master Nowak responded, his grey eyes without a hint of impatience. “More importantly, the guild protects us. It regulates the market and supports us when we purchase amber. It helps apprentices find work. We need the guild.”

“But why can we not just do our work and sell it without the guild?”

“That is the way it is.” Master Nowak sighed. “We cannot operate outside the guild. Nobody would buy from us.”

“It is not fair. The guild sets the prices. The guild controls what we sell and to whom. The guild tells us what methods of working with amber we should use. And we are not even allowed to walk on the beach—our beach, in our land. It is like being in jail.”

“Better this ‘jail’ as you call it than being out there, all alone, without the protection of the guild. Think of all the guild does. The guild helps when there is a fire or a flood. It builds hospitals, schools, and orphanages. The guild even pays for funerals and masses. Without the guild, you might as well become a Bönhase.”

Peter shook his head in frustration as he thought about what Master Nowak had said. Bönhase came from a word meaning “a hare hiding in an attic.” A Bönhase was a worker who crafted and sold amber in secret. Operating outside the law, without guild certification as a journeyman or master, a Bönhase was always at risk of being found out—a hunted hare, with hounds right behind it. Then again, it had to be wonderful to be independent.

Peter pulled his coat tighter around himself against the wind. Occasionally he stepped into a depression filled with water, but it did not bother him. The sound of the waves soothed him; he felt as if he could breathe more easily. He dreaded the weight of his father’s unhappiness, the lingering sadness over his brother’s death, and the weaving and rocking from side to side his sister engaged in when she was upset. There was no room for Peter in any of this.

To get out of the wind for a while, Peter crawled into a little hollow beneath exposed roots of a stand of scraggly pine trees. Riding along a path on top of the dunes, the beach watchman would patrol the area, on the lookout for people gathering amber. The tide was going out but the sea was churned up by the storm, and gusts of wind continued to whip across the water. Occasionally the spray from breakers hitting the beach tickled his face and his lips tasted salty. The smell of the sea and the incessant slap of the waves onto the shore gave him the feeling of being worlds away from Master Nowak’s disapproving frown or his father’s gloomy dissatisfaction.

Absorbed in watching the shimmer of the water in the glow of the setting sun, he felt his thoughts calm down. Perhaps he could find a way to escape from all this. He began to dream of journeying far away, perhaps to the city of Königsberg, the heart of the amber trade. It would be marvelous to come upon a hidden cache of amber somewhere along the fabled amber beaches outside of Königsberg. Of course, he knew there was nothing more unlikely. He thought of the tales told by amber fishers who claimed to have seen large chunks of amber floating in the waves. Whenever they got closer, reaching out with their nets, it all vanished.

Peter ran his hand back and forth over the sand and the exposed gnarly pine roots near his legs, then stopped, wincing. He had cut the sensitive area between thumb and index finger.

Thumping sounds made him raise his head. The silhouette of a horse and rider loomed against the darkening sky—the beach watchman, cantering along the path on top of the dunes.

Peter squeezed farther back into his shelter, his foot digging into the sand. The ground reverberated as the rider thundered past his hiding place. Sliding down as if a sinkhole had opened up beneath him, Peter grabbed onto an exposed pine tree root to keep from making noise and attracting the watchman’s attention. The horse started and snorted as if sensing Peter’s presence. The rider cursed, kicking the horse, and within moments, passed by. The sounds of the hooves in the sand faded away.

Peter was still clutching the root with one hand when he felt a lump underneath the other. Slowly he sat up and tried to pull his find out of the sand, tugging until it was free. He shook it to dislodge some of the sand. The clump smelled bad; it was nothing but rotted netting, with barnacles and small shells caught in its coils. Disappointed, he raised his hand to toss it away.

Then Peter hesitated. The dark stringy strands reminded him of the nets used by the amber catchers. He could feel something firm inside the tightly twisted mess of rope and knots, and worked his fingers into the tangle, pushing and pulling until he was able to pry it apart. A salt-crusted stone with a rough, cracked surface fell onto the sand in front of his feet. He picked it up to take a closer look. There actually were two pieces, a longer one, about the length of his palm, curved around a smaller one, like a mother cradling a baby in her lap. When he prodded the clump with a little twig, the pieces came apart. These were not stones. They were too light.

Amber.

Instinctively Peter closed his hands over his find and glanced around to see whether the watchman was coming back. The tops of the distant pine trees waved in the wind. The beach was deserted, and the only sound other than the surf was the raucous screeching of the cranes.

After a moment, Peter relaxed, opening his hands to study the lumps. Dull, crusted with salt, unpolished, they did not look at all appealing. But he had worked with Master Nowak long enough to know at least one of them to be a unique and unusually large piece of amber. On the amber market, it would fetch a high price.

The smaller piece was just large enough for a lady’s pendant. Peter could see it with his mind’s eye as clearly as if he had spent hours working on it—a perfect little heart with a warm dark golden glow. He put it down and picked up the other one.

It was almost as long as his hand and half as wide in the middle. In the workshop, he rarely handled or worked on pieces larger than those used to make rosary beads. He poked at the crusty surface with his fingernail. He turned it this way and that. It made him think of a tall bird, perhaps a crane. Its oblong shape seemed curiously alive, as if a bird was waiting underneath the crust, dreaming inside its dark golden nest.

It rested on the palm of his hand, its secret hidden. He should throw it back. Someone might have seen him walking toward the beach. It would be awful if he were caught. He would have to count himself lucky if he only got flogged. He should throw everything back into the sea immediately. The watchman might come circling back any moment. He closed his hand firmly on his find and lifted his arm. Then, as if pulled down by a tremendous weight, his arm dropped. Just for a night. He would keep it just for a night. Tomorrow he would take it back.