- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

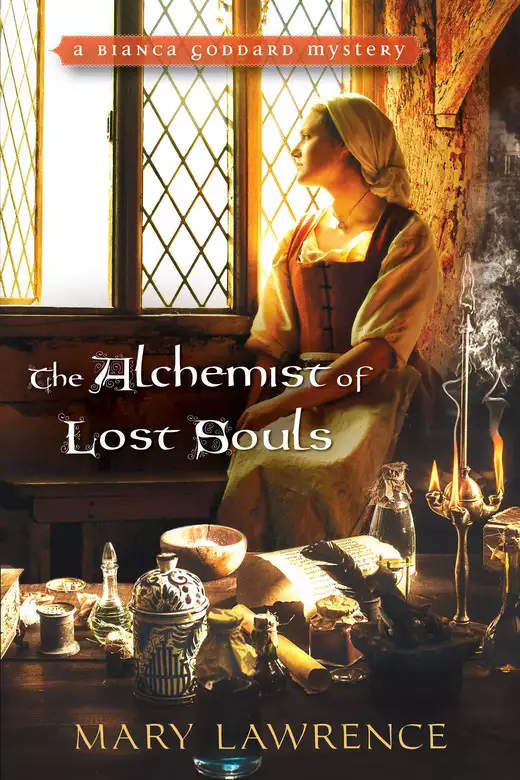

Synopsis

A dangerous element discovered by Bianca Goddard’s father falls into the wrong hands . . . leading to a chain of multiple murders.

Spring 1544: Now that she is with child, Bianca is more determined than ever to distance herself from her unstable father. Desperate to win back the favor of King Henry VIII, disgraced alchemist Albern Goddard plans to reveal a powerful new element he's discovered—one with deadly potential. But when the substance is stolen, he is panicked and expects his daughter to help.

Soon after, a woman's body is found behind the Dim Dragon Inn, an eerie green vapor rising from her breathless mouth. To her grave concern, Bianca has reason to suspect her own mother may be involved in the theft and the murder. As her husband John is conscripted into King Henry's army to subdue Scottish resistance, Bianca must navigate a twisted and treacherous path among alchemists, apothecaries, chandlers, and scoundrels—to find out who among them is willing to kill to possess the element known as lapis mortem, the stone of death . . .

Praise for Death at St. Vedast

“Full of period details, Lawrence’s latest series outing captures Tudor London in all its colorful splendor. A solid choice for devotees of Karen Harper’s Elizabethan mysteries.”

—Library Journal

Release date: April 30, 2019

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Alchemist of Lost Souls

Mary Lawrence

This tale begins with a rascally lad and a disgraced alchemist. One sought allowance with a group of puckish boys, and the other wished forgiveness from his petulant king. The two crossed paths one spring day when the air puffed warm against their cheeks, calling to mind the hope of renewal that comes with the lengthening days and appearance of green tips on trees.

Albern Goddard wore his best woolen gown, one he’d bought from a fripperer back when he was in the king’s good graces. The clothes dealer had gotten it from the widow of a barrister who had been stabbed in the back—a fitting end to any lawyer, thought Albern. The rip had been mended and the bloodstain scrubbed clean. No one was the wiser, and he himself barely remembered the gown’s tainted history as he strode triumphantly down Thames Street.

His coif did not hide the lift of his chin; the scholarly garb accentuated his proud posture—for here was a man basking in the ticklish glow of divine favor. A smile strained the muscles around his mouth; his usual expression was one of stoic indifference. And that was on a good day.

He may not have discovered the philosopher’s stone—the coveted agent of transmutation capable of turning base metal into gold; instead, he had discovered a substance of unplumbed worth. Of this he was certain. Months of collecting and fermenting the golden stream—his golden stream in urns stinking up his alchemy room—had eventually wrought a substance so astonishing, so exceptional, that he could hardly keep from whooping and dancing down the street.

However, unbridled enthusiasm can easily turn a man into a fool. The alchemist knew this; he had eaten from fate’s fickle hand before. So, he quashed the smile on his face, replacing a cheerful expression with one more solemn. Ahead of him lay several days of careful analysis to prove his discovery’s importance.

Meanwhile, on the street ahead, there lay an ambush in the form of a gaggle of gamins. Their winter boredom had festered, so that this day of sun and warmth was like a needle to their boil, releasing the hellions to run free.

What boy can resist the call of his friends’ mischief? After a winter of trudging through cold, wet lanes, lugging home bundles of sticks for his mother’s fire, of being cooped up with his siblings like chickens kept from wolves, of listening to the constant wails of younger kin, what lad of any spirit could suffer another moment staring at four cracked and soot-grimed walls? So it was that on this day, a boy with threadbare britches and raggedly hair wandered farther than was his usual habit.

He hitched himself to a group of boys kicking a pig’s bladder stuffed with hay. Other stragglers left their chores to join in, and soon there was a mob of exuberant, yelling imps tripping over one another and upsetting geese, pushcarts, and pedestrians. They raced around, calling each other “lead-legged” and “beetle-brained buzzards.” They ran down Bread Street and exited onto Thames Street just as Albern Goddard was crossing it. The ball rolled to a stop inches from the alchemist’s shoe.

His serious face drew the boys to a scritching halt. They stared wide-eyed at the person standing before them. Deeply set gray eyes glared back, unamused. The man’s exceptional gown bespoke a person of import, but when they ran their eyes down his august garb, down his black netherhose to his shoes, they found a pair of leathers as haggard and as somber as he.

The alchemist looked down his nose at them. He picked up the bladder ball and turned it over in his hands, still studying the unruly herd of boys. Not until every eye had met his did the alchemist release the ball, turning and throwing it back in the direction he had come. Like a sorcerer he released them from his spell and the boys ran after the bladder, hooting and yelling.

But a handful of boys remained where they were. The novelty of the sport had worn off in favor of this odd person now striding down the street. These boys did not suspect that the man was an alchemist. They didn’t know what he was about, but they saw an opportunity to antagonize the pretentious man just the same.

They fell into line a safe distance behind, imitating the alchemist’s heron-like stride. His long legs jutted out as if they bent forward at the knees. A few citizens paused to titter at the boys’ mockery, and this only emboldened them to exaggerate their gestures. They mimicked wearing the sweeping gowns of learned professionals and dismissively flicked their wrists to discount any who looked their way. The lads deserved a good cuffing about the ears.

One of them crept closer to Albern and brazenly threw a rock. The missile sailed within inches of the alchemist’s ear. Though he must have heard it, he seemed not to notice. His pace never slowed, his head never turned. However, ignoring the boys only provoked them further. They made obscene gestures. They called him a rooster, laughing. They cock-a-doodle-dooed louder than the squeaks of cart wheels and the clopping of horses—but their mockery had no effect. Goddard’s focus stayed on his single-minded purpose.

Some of the boys became discouraged and abandoned their efforts. When their quarry was waylaid by a conversation with another man, the remaining scamps grew bored and ran off to find trouble elsewhere. All except one.

Timothy Browne ducked behind the support poles of a produce stand and watched. From where he stood, he could hear the puff-cock address the other man in a patronizing tone. Even though Timothy was a simple boy of nine and was unsophisticated in the nuances of adult conversation, he sensed the condescending quality of the fellow’s reaction to the inquiry of the other and took exception to it; for the man to whom the fellow was speaking was his father.

Dikson Browne was an alchemist, one who’d fallen on rough times—but then, to Timothy’s knowledge, his father had never known good ones. Like most alchemists, he had squandered his family’s resources and they always seemed to be living on the edge of despair. Timothy noticed his father stiffen as he spoke.

That this other fellow seemed smug was obvious to the boy.

“I sense that I am delaying you, Goddard. Have you discovered the stone?”

Timothy caught the man’s name and remembered his father’s barbed comments about the fellow on more than one occasion.

“Nay, I shall leave that pursuit to others more inclined.” Goddard tilted his head. “Dikson, why do I have the fortune of chance meeting you? Who is watching your latest chemistries?”

“Oh,” said Timothy’s father, straining geniality. “I am at a stage where the projection must rest.” But Timothy thought the only thing that rested in their home was his father after too much drink.

Goddard attempted a smile. “Well, my good sir, I wish you every success. A fair day.” And with that, he tucked his chin, stepped aside, and sallied on, leaving Dikson Browne gawping after.

Timothy Browne, watching the curt exchange, felt sorry for his father but quickly turned his back when Dikson stopped glaring after Albern and glanced his way. Pretending interest in hay-stippled fleeces, Timothy waited until his father had moved on, then searched the road for the arrogant alchemist. He caught sight of Goddard—the man’s height easily setting him apart from others—and scurried down the lane after.

Thames Street happened to be the longest thoroughfare in London. The boy had never explored its entire length stretching from St. Andrew’s Hill all the way to the Tower. This morning, his mother was keen to be rid of him and, as long as he returned in time for supper, he could do as he pleased. He followed Albern Goddard past the old church of All Hallows the Great, where the beseeching left hand of a stone carving of Charity had been lopped at her wrist. All Hallows the Less stood a few yards beyond, living up to its name, abandoned and home to vagrants. A young dog trotted cheerfully beside him, and he threw sticks for the pup until a butcher cart en route to market led it astray. Then Timothy ran ahead, looking for the tall alchemist, spotted him, and fell back to stalking.

Eventually the man turned into an area of warehouses near Billingsgate, with its merchant vessels bobbing at the wharf. He twisted through a warren of rubble stone buildings to an area of derelict ones made of wood. At one of these leaning structures, Albern Goddard stopped. He worked a padlock held with a rusty chain, and after a moment the heavy impediment fell away and he slipped inside.

Timothy cautiously approached. Looking left and then right, he hesitated opposite the door and leaned an ear against it. No sounds ranged within, but when the door suddenly shook from the weight of a deadbolt being secured, he let out a yelp and fled around the corner.

The door rattled open. There was a pause, a slam. Timothy blew out his breath. Listening at the door would be risky; the man might skin him like a rabbit and no one would know the better what happened to him.

The lad considered going home, and had taken a step in that direction when a loud creak issued overhead. A pole pushed open a high window that resisted being prodded. He crouched behind a barrel as it fell shut, then finally was gotten under control and propped open.

Boys have the curiosity of cats but lack a feline’s guarded stealth. Timothy noticed he shared the cramped alley with an abundance of discarded crates and barrels. The smell of rotting wood and mildew permeated the air. However, if he could properly stack them, he could scale a ramshackle tower and have a look inside the alchemist’s room.

Testing several barrels, Timothy found one strong enough to support his weight and rolled it under the window. The crates took more effort to arrange, requiring him to balance on the remains of those less sturdy while placing one atop the other. Soon he had built a tottering structure that could withstand his climbing it.

The construction wobbled and threatened collapse as the boy picked his way to the summit. Once there, he stood upon his toes and, careful not to disturb the support pole, poked his head under the window frame to peer inside.

As his forehead rose above the sill, the first thing he spied was a set of fierce-looking teeth. It says something of the child’s background that he did not flinch upon seeing such a sight, as most boys would have at least lost their balance. Timothy, though, searched beyond the glinting enamels to the desiccated remains of a creature hovering at eye level and suspended from the rafters. A crocodile. A layer of grime covered its scaly green-gray hide, turning it into a less formidable creature, dangling with writhled skin, dull with dust. He had, after all, seen one before.

His own father’s room of alchemy was a garret from which pigeons were shooed in the uppermost reaches of his family’s rent. On the rare occasion that Timothy had seen inside, he found a room a quarter of the size of this, and not nearly so well stocked. The boy marveled at the array of bottles and bowls lining the shelves in this room of alchemy. A variety of furnaces, one he recognized as a fusory furnace for melting metals, sat against an exterior wall, where a smaller window provided some escape for the caustic fumes that spewed when it was stoked. Large, pelican-shaped, still heads balanced atop copper cucurbits. Clay pots and urns littered the floor, and wavering plumes of smelly smoke escaped lit tallows. This was a proper alchemy room, not the sad imitation in which his father toiled.

At first he did not see the alchemist unlocking a cabinet against a wall. The man had removed his scholarly gown; his brown jerkin and dark hose blended into the drab palette of the room’s interior. Presently, the cabinet door fell open.

If he had not witnessed it for himself, Timothy would have sworn that a lantern had been left burning inside the cupboard. A brilliant white light illuminated the alchemist’s face, emphasizing his lengthy, thin nose and wiry eyebrows. It was not a lantern of any type with which the boy was familiar. No metal housing encased it; rather the light filled a bulbous-bottomed flask. The boy blinked. How could it not have burned down the room? Timothy leaned forward. What was this strange spectacle?

The alchemist smiled as he withdrew the flask glowing bright with the luminous intensity of a full moon. His eyes widened as he lifted the vessel and admired it.

Astounded, Timothy drew back, bumping his head on the window. The pole wiggled free, balancing in midair for a moment before he grabbed it. With a trembling hand, he repositioned the prop against the window, holding his breath until he was sure the alchemist had not noticed.

He need not have worried. Enthralled (or perhaps blinded) by the light, Albern Goddard set the flask on a tripod and pulled up a stool to sit. Neither candle nor lantern, this light did not flicker but remained a steady, robust glow.

The boy did not know how long the two of them gazed at the flask. He was sure he was witnessing something unique, perhaps even magical. At one point, the alchemist adjusted the cork. Eventually, though, the brilliance faded and the glow diminished. It changed to an eerie green, then vanished, snuffed like a candle.

The alchemist stirred, rubbed his neck, stretched his limbs. He fetched a pair of tongs off a nearby furnace, set them on the table next to him, twisted out the cork, and laid it on the board.

Immediately a crackle and spark erupted inside the flask. The crackling grew, sounding like ice shattering on a puddle. Flames began spewing from the flask. The alchemist shoved the stopper back in the opening and nearly dropped the vessel on the table. He yowled and cursed, Timothy thought, from being burned.

After a few minutes, the fire lost its strength; its dance diminished to a gentle ruffling of flames, then died.

Timothy frowned. Removing the stopper had freed and restored its vigor—much like the boys who had been released from their winter captivity. Stoppering the end of the flask had tamed it.

What could one do with such a thing? Timothy began pondering the possibilities, all of them having to do with making money and garnering awe. It didn’t seem right that this toffish prig of a puffer should enjoy the fame that might come from its possession. His family would be better served.

Goddard crossed the room to his shelves and surveyed the collection of bottles, some with labels, most without. His head dipped, then rose, like a strange bird assessing a beetle. He gripped the neck of a plump-bottomed decanter and removed its plug to sniff its contents. Satisfied, he cradled it back to his work area and poured a small amount into a cup.

Timothy watched as the alchemist again removed the cork. Taking hold of the tongs, he tilted the vessel to work them through the narrow opening. The crackling began and sparks flew up the neck of the vessel. The alchemist worked quickly, fishing around until he withdrew a piece of material the size of a pea and dropped it in the cup.

Albern hurriedly replaced the cork, giving it a forceful twist, and the glow in the flask continued for a bit, then eventually faded. The lump in the cup, however, did nothing. The alchemist sat on his stool and stared at it. He poked it with his tongs.

Timothy, unimpressed, grew bored. His stomach told him dinner was nigh upon him, and if he did not return by the time his mother called for him he’d suffer more than just going to bed hungry. The sun was somewhere beyond Bridewell and soon the starlings would be lining the eaves of St. Martin Vintry. He was ready to end his covert surveillance when he smelled a strong odor of garlic. He rocked onto his toes and peered back inside.

Smoke billowed from the table, nearly obscuring the alchemist on his stool. It quickly grew into a cloud, doubling in size. Timothy could hear the man coughing and even he could not keep from gagging over the pungent smell wafting past his nose. He didn’t worry that the alchemist would hear him; the man was cursing and trying to fan away the encroaching storm, trying to find the little lump and do something with it.

Sparks pierced the swelling cumulus, reminding Timothy of a fireworks display he once saw over Hampton Court Palace. No celebration here. An orange flame shot up from the table and he glimpsed a look of fear on the alchemist’s face as it singed the man’s beard and lit it on fire.

Frightened, Timothy jumped back. His head knocked against the window and sent the pole toppling. He hardly had time to care before his tower gave way under his shifting weight, and with a terrified shriek he rode the bumpy slope down to the ground, landing in a heap next to a pile of splintered crates and barrels. Rubbing his bruised bum, he glanced up at the smoke pouring out of the high window.

Timothy sprang to his feet. What became of the alchemist or this sorry row of warehouses wasn’t his concern. He imagined his mother’s voice calling, her bellow echoing through the streets of Queenhithe Ward, through Romeland, reaching him in this dank alley behind an alchemist’s room. God help him if he was late.

On the opposite bank of the Thames, the marshy fields of Southwark had also noticed winter’s passing. Thriving on consistent days of warmth, the grounds beyond Paris Garden and the bull-baiting venue had erupted in a carpet of wildflowers, none more impressive than meadowsweet. By right the queen of the meadow reigned supreme in this patch of competitors. At the end of startling red stalks her delicate flowers bowed to the breeze, rippling like tatting on Katherine Parr’s sleeve. Fie on anyone who dared mention she was common. She was no dropwort, so mundane and undignified.

Beyond that field was another plot of ground with more martial purpose. Archery butts lined one end of it, the mounds savagely stabbed with arrows. At the other end, some two hundred yards opposite, fifty men of military age gathered, waiting instructions. All of them held bows of some fashion, either of yew (for those more serious and of some money) or of wych elm (for the rest).

On his way to join them was John Grunt, Bianca Goddard’s husband.

The king’s law required that every man between sixteen and sixty years must possess a warbow and practice his archery skills (though if a man were to achieve that ripe age he would need a cart to haul him to a field of battle). One never knew when their foe (namely, the French) might invade and try to seize their fair isle. No matter that Henry was the more likely instigator of any clash between the two realms. With His Majesty keen to relive the glory days of his youth and with the season for war drawing near, a summons had been ordered for the men of Southwark to congregate beyond Broadwall for the evaluation of their archery skills.

John loped at a pace commensurate with his lack of enthusiasm. He cared not a sliver that he was late—his inability to locate his bow had assured it. First impressions made little difference to him. Once the officers had noticed his strength, he was as good as gone. Years of working as an apprentice to a coiner had plumped up his muscles, and his above-average height would make him a desirable asset.

“It will do you no service if you miss the butts,” said Bianca, walking beside him. “And do not dawdle on my account. I can keep stride with you.”

John glanced over and his eyes fell to her stomach. A worried look came over his face. “I should shoot myself in the foot.”

“And pretend it an accident?” Bianca lifted the hem of her kirtle as she picked through a soggy stretch of road. “Do you think that I cannot fend for myself?”

“Nay, it isn’t that.”

“You think I will do something foolish and lose our child?”

John’s reticence was her answer. She looked away, biting her tongue to keep from using it to argue.

“I worry that I cannot help if I am away spearing Frenchmen. If I broke an arm I’d be of no use to the army.”

“If you broke an arm you’d be of no use to Boisvert, or to me for that matter. Prithee, what would you do to ‘help’ as you say? Birthing is not a man’s chore.”

“I could send for a midwife.”

Bianca looked askance at him.

“Bianca,” said John in response. “If I should be conscripted, I might not live to see our child.”

“John, if you broke your arm you might not live. Worrying will not prevent us from knowing sorrow. Why color today with black thoughts? The future will bring what it will.”

And indeed, it had; her pregnancy had come as a surprise to both of them. Bianca had taken “precautions” that she did not openly discuss, not even with John. After all, one should not thwart God’s purpose for a woman. Doing so was a sin. However, she was not the only one to use herbs to try to prevent God from getting His way.

Her mother often chewed handfuls of wild carrot seeds during a gibbous moon. “To prevent the abdomen swelling,” Bianca was told. When Bianca’s own “time” had come, her mother fashioned a plug out of bog moss and explained the finer points of a woman’s expected function, then told her in sworn confidence how to prevent it. It was not lost on Bianca that this education was probably necessitated by her mother’s desire to prevent her from suffering a similar fate. Her parents’ marriage was not an amiable one.

It was not Bianca’s nature to wonder whether her mother regretted birthing her. Instead, she saw the inconvenience motherhood might pose in her own life. She would have preferred to postpone the responsibility. John had not finished his apprenticeship, and they relied on Bianca’s earnings from medicinals to help feed them. Besides, Bianca was not ready to set aside her curiosity to care for a child. But the future had brought its own will to bear upon their lives, and Bianca had no choice but to accept it.

“I can’t remember the last time I shot an arrow,” said John, plucking the string of his bow. Then, remembering he’d forgotten his bracer and finger guard, stopped in his tracks and swore. “I’ll turn my arm into minced meat.”

Bianca reached into the pocket of her apron and handed him the leather guards. “I pray you make an effort to impress them. It is far more dangerous to be a billman.”

A horn blew and the gathering turned their attention to a mounted nobleman—a captain splendidly dressed, wearing a bonnet with a red-dyed plume and a satin white jacket shimmering in the morning sun. He was accompanied by several soldiers, a gentleman pensioner, and a sheriff, each riding their own fine horses, though the sheriff’s was a little less fine. The captain forwent any introduction, assuming, wrongly, that his name was known, and divided the men into three groups behind a scored line.

“You’d better get on,” said Bianca, urging John ahead. “Shoot well.”

John took a step, then turned and held Bianca close, seizing a hearty kiss before trotting off; a sure sign the lust for competition was coursing through his veins.

Bianca watched him fall into line with the others, then joined the company of spectators. From where she stood, she could see John had settled himself. He stood nearly a head taller than most. Chin level, John knew how to exude confidence, or at least affect it. There was no use in pretending incompetence because failing would only land him in a worse position. Archers had the benefit of distance in battle. They had pike and billmen to go before them.

The captain shouted instructions to the first row of archers while a soldier dispensed a quiver of arrows to the first in each row. To start, they were to shoot two arrows on command. Each man would have his opportunity; then they would be tested for speed and accuracy.

Onlookers quieted as the first group selected their arrows. The captain waited until the archers squared, then shouted, “Nock!” His voice carried over the murmuring crowd and screech of seagulls circling over the mudflats. The archers set their arrows on the string.

“Draw,” commanded the captain, and the men raised their bows, pointing the arrowheads at the sky and pulling the string to maximum.

“Loose!”

A bevy of arrows arced down the field toward the waiting butts. Only two of the men managed the distance, their arrows hitting the earthen mounds with a solid thwack that sent puffs of dust into the air.

The captain and his cohorts looked at the targets. Results were recorded in a log as the captain looked back at the archers. “Again!”

With each successive archer, each “nock, draw, and loose” order, the mood of the crowd grew increasingly somber as each man’s fate became clear. There were those who shook from their toes up and whose arrows flew wild because of it. Others could have hit the target standing on one leg. Bianca watched John move up in line. To his benefit he had physical strength and composure under duress. To his detriment—his negligence in practicing.

As Bianca waited for the archers to cycle through their turns, she mused on the man she had married. He had been her husband less than a year, but they had known each other since they were twelve. A mischievous childhood defined them—neither had been curbed by doting parents and John was an orphan. Both had learned to survive by their wits. By the time they met, Bianca was an effective cutpurse and John excelled in scavenging through barrels of rubbish, though neither of them performed their knavery with absolute success. If Bianca had not been caught filching sausage from a butcher’s stall, their paths might never have crossed—or rather, their paths might have taken longer to curl through the streets and back alleys of London and eventually meet.

John had saved Bianca from the sweaty hands of an odious constable eager to make an example of her by whacking off one of her fingers. The constable had gripped her ear and John had stared at her until her eyes found his; what passed between them in that brief exchange went. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...