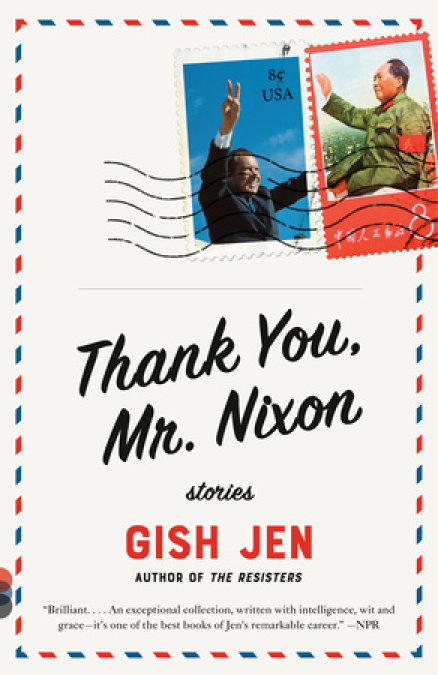

Thank You, Mr. Nixon

Mr. Richard Nixon

Ninth Ring Road

Pit 1A

Dear Mr. Nixon,

I don’t know if you will remember me, especially now that I am in heaven and you are in hell. I was one of the little girls you talked to when you came in 1972. Do you remember? Not the one in the famous picture. I was the other one. We were in a park in Hangzhou. That was your other stop besides Beijing and Shanghai, a famous place with a beautiful lake called West Lake. It was February, and you mostly had your hands in your pockets. Maybe your fingers were cold. First you talked to the girl whose mother was right behind her. Of course, she smiled just the way she was supposed to, and someone took that picture. Then you talked to a little boy who was dressed in a new coat but who was actually supposed to be in the background; that’s why he did not know which hand to reach out when you wanted to shake hands. Everyone laughed, but some people worried because they did not think you would talk to the boy. That was not the plan. And I was very embarrassed, but you did not seem to notice, just as you did not seem surprised that it just so happened that the two girls you happened to run into in the park were wearing such beautiful coats—so new and perfect, kind of an orange-pink color. Nor were you surprised that, when you asked where my mother was, I said, In the city. Shouldn’t you have wondered what I could mean, since we were in Hangzhou, and Hangzhou was a city? In fact, my mother was living in Shanghai then, because she had been assigned to a unit there. But probably you had no idea people were assigned anywhere. Anyway, my red scarf was a real red scarf; that really was what we wore if we were Little Red Guards, and I really was a Little Red Guard. But that was not my real coat. Actually, my mother had to piece it together out of two other coats. Because she sewed for a factory, though, it came out just as if it were made in a factory.

—

Really, the whole China you saw was a tailor-made China—a Potemkin China, you might say, not that anyone would have said that then. That is only how we talk in heaven, where we know all kinds of things. For example, we know that today there still are a lot of things you cannot say in China. But back then there were even more. And while today you have to guess what you can’t say, back then they would just tell you. No one was allowed to shout Down with the American imperialists to your face. On the radio and on TV, too, the phrase American imperialists just suddenly disappeared, as if everyone forgot it all at once. Which no one thought was particularly strange. We all knew how to forget, after all. We were good at it—experts, you might say. And if there was a face we had mastered, it was a stone face, for things changed all the time. One day Comrade Lin Biao was a hero, for example. The next day we forgot he was ever there.

The streets were cleaned up before you came, with certain slogans removed and new ones put up. The shelves of the stores were filled, and people were made to stay at school and work late, so that the streets would not be so crowded. Did you notice how few people there were around? Maybe you thought that was normal. But it was not normal, just like the number of fish in West Lake was not normal. Did you think there were always so many beautiful carp, waiting to be fed? Those of us students who were supposed to be background students in the park were told what to understand. What if the American journalists asked things like Do you have enough to eat and drink? or Do you like America? our teacher asked us. Do you understand them? Of course, that was a stupid question because anyone who answered yes would not have been picked to be a background student to begin with. But no one said it was stupid. Instead we promised that even if the translator spoke perfect Mandarin, we would not understand him. We were not supposed to understand anything about a man going to the moon either, which was easy since most of us did not actually know the American imperialists had put a man on the moon until we were told we didn’t know anything about it. As for whether we were supposed to volunteer, We had gangs of Red Guards breaking into our homes and destroying everything, much less, They took people out into the yard and beat them to death, or The young people were sent down into the countryside to be reeducated but also just try to stop them, they were so out of control, you may guess whether we were supposed to say these things or not.

No—we were smart. And having been told to be neither humble nor arrogant, neither cold nor hot, we were exactly that, though I was so happy in my new coat, it was hard not to be warm with happiness. Indeed, I thought it the most beautiful coat in the world until I saw your wife’s red coat. Can I call her Pat, now that we are all dead? She did not wear her red coat to the park. That was a disappointment. At the park she wore a fur coat, maybe because it was so cold. But I saw the red coat later, and anyway we students all knew about the red coat. We had heard about the red coat. It was already a famous coat. Of course, we understood, too, very well, that we did not love it. Though China had become a sea of dark blue and gray and black, with just a little color allowed for us children, for everyone else a red coat was bourgeois, after all. It was antirevolutionary. It was corrupt and corrupting. Couldn’t we feel its pull? That was because it was venal. Imperialist. American. Beautiful.

No, we did not love it. We did not think how suitable it was that a beautiful coat came from a country whose name in Chinese literally meant “beautiful.” China might be Zhongguo,the Middle Country, but America was Meiguo—the Beautiful Country.

A beautiful country full of beautiful coats. What could that be but evil?

The history books say that China opened when you shook hands with Chairman Mao. But I think it began with that coat. Because if on the outside we were neither humble nor arrogant, neither cold nor hot, on the inside we were torn. We loved our country, but it was not red flags we wanted. It was red coats.

Thank you, Mr. Nixon, for bringing that coat.

Here in heaven, we know much more about your situation than we did back then. It is terrible that people in your country called you Tricky Dick. That is so much more personal than plain capitalist running dog or petty bourgeois individualist. And it is terrible that they made so much fun of you because of your sweat. Is that why you wore makeup when you were in China? Up here in heaven there is an American interpreter who says he accompanied you on your visit, and that he once saw a glob of pancake makeup hanging down from a hair in your nose. Of course, if American people did not like for their leaders to sweat so much, that is something Chinese people can understand. Really, it is just lucky that we are not as sweaty as you; also that we do not have hair in our noses. And maybe you knew that pictures were going to be taken of you all day, historic pictures, and maybe you did not want for your nose to shine for everyone to see forever. So you put on some makeup. From our point of view, that was okay. As for how upset the American people became when they found out not long after your visit that you had asked some people to break into a hotel room and steal some papers, that we did not understand. Certainly, it was not so good.

But from the Chinese point of view, it wasn’t that bad. Think about how many people Chairman Mao killed, after all. Of course, between Vietnam and Cambodia, you had some blood under your fingernails, too. But Chairman Mao! Even here in heaven, no one can say how many people he killed, between his crazy ideas and his purges—whether it was 45 million or just 25 million. Scholars are still bashing clouds over this; maybe they just miss arguing. But let’s just say that no one claims Mao killed, say, 4 or 5 million. Because we need to be careful: if the angels laugh too hard, they can fall off a cloud and crack a halo. Our sweet Chairman Mao was unfazed even by the thought of nuclear war. If worst came to worst and half of mankind died, he said, the other half would remain while imperialism would be razed to the ground. And then? And then the whole world would become socialist, he said. I guess he was what today we might call an out-of-the-box thinker. Of course, some people said he gave China back our pride, and that is true, too.

Anyway, you can see why I myself am not sure you should be in hell, much less in the ninth ring. And in the first pit! Didn’t you lose your job when you were alive? Wasn’t that punishment enough? And mister, but it scared the Russians, to see China and America make friends! That was something only a redbaiter like you could have pulled off.

My family did not have a TV, but there was one in the village leader’s house. It was black and white, naturally, so we all knew even before he set it up that we were not going to be able to see Pat’s red coat—or my pink coat, either, if the program included Hangzhou and I was in the program. Still, he put the TV on a beautiful lace doily on top of a piece of plastic on top of a wooden table, and attached three extension cords one to the next so he could make the TV work. Also, he hung my coat up on a chair beside the TV, so we could all see what a beautiful color it was. That village leader was actually a kind of artist. He could paint anything and always encouraged me to paint, too, even if my father did not like it. But, whatever. As there were no chairs, and the ground was cold, we all squatted to watch the program.

From the beginning to the end, we watched. I was not in it. Still, my father thanked the village leader with some cigarettes and said that he would tell my mother how much the whole village admired the coat. As for myself, I helped put the TV away and never forgot the village leader’s kindness. It was very sad when he was criticized a year later. My father participated in the group criticism and was angry that I refused. But I could not participate. It was just lucky that when I pretended to be sick, people pretended to believe me. My father gave my beautiful coat to the new village leader’s wife for her daughter, just to be sure.

For months after you went back to America, I drew pictures of people in red coats. People I knew, people I didn’t know; I even drew animals in red coats. When people asked me about them, I said they were Red Guards. But of course, the Red Guards wore red armbands, not red coats; these were all ghosts of your wife, Pat. My mother, who would have come back to live with us if the new village leader hadn’t blocked it, told me to stop. But one day I saw her looking at her reflection in the window, and she had her fingers in her hair. And now that she is here in heaven and can have whatever hairstyle she likes, I see she is wearing it to look like Pat’s.

Back then, you know, I used to hum the American songs they played during your visit. “The Star Spangled Banner.” “Turkey in the Straw.” “America the Beautiful.” And I wasn’t the only one. I had many friends who hummed the songs. We loved them all. But the song we loved most was “Home, Home on the Range.” No one knew all the English words, but we understood that it was about home—we understood that “home, home” meant jia, jia. We understood its heart. Home was where my mother wanted to live again. Home was where I wanted her to be. And I guess you could say it was one more thing that confused us, that heart. How could this be an American imperialist song?

The more we thought about it, the more we felt you were the best enemy we had ever had, Mr. Nixon.

Maybe it is no surprise that when China opened its door to the West, my family jumped into the capitalist sea right away. My father kept his job in the No. 6 chemical factory for a while, but my mother retired immediately and moved back home, where we started a small coat business. As we did not yet dare design our own coats, I copied famous designs from abroad, starting with your wife’s coat. Of course, we had to make the coats in dark blue and black and gray because those were the colors we had. Still, the design was beautiful, and my mother was good at sewing, and we soon realized that if we made the coats big enough for the foreign tourists who were starting to come to visit, we could sell them in the street markets. And sure enough, the foreigners liked them, especially if we tailored them to fit perfectly and added whatever pockets or plackets or cuffs the foreigners liked. We did this overnight, too, which impressed them. And then it turned out my mother’s friends in Shanghai could sell coats in the street markets there, and quickly learned to do the same thing—to customize the coats overnight or even on the spot. And everyone was happy.

Our little company was successful. But after a while the foreigners began to bring our coats back to their countries to sell, and that made people dissatisfied. Because it turned out people in America did not like coats that said “Made in China,” for example. A nice man explained that to us, his name was Arnie Hsu—an Overseas Chinese man who had come to visit his teacher brother. Actually, his teacher brother had only just come with him to help him buy a coat. But he could also translate when Mr. Arnie said that the problem was something called “prejudice.” If you took a coat and said it was “Made in Italy,” he said, American people would like it very much. But not “China.” They did not like “Made in China.” Because of this “prejudice.”

So why don’t we change the label to say “Made in Italy”? my father said.

An excellent question, Mr. Arnie said. We couldn’t because if the American authorities found out, they would be mad and confiscate everything. So that was a problem. However, after we talked a little more, he thought of a way around the problem. He said that he had heard some factories had closed down in Italy. So if we bought a factory and did just a few things there, like sew on the buttons or put in the lining, maybe we could label the coats “Made in Italy.” And then American people would buy them.

Buy a factory? In China we did not have such ideas. How could we buy a factory? And where was Italy? And how could their factories be closed? Even Mr. Arnie’s teacher brother was surprised by the idea.

But Mr. Arnie was smart. He said he knew some people who knew all about this kind of thing. A family by the name of Koo; they lived in Hong Kong. He said he would ask them.

And sure enough, he asked them, and it worked. In fact, Mr. Arnie made such a good arrangement, the Italian people were angry at us, even though actually, we were happy to employ them. And actually, we really liked them. We liked their food, never mind if they copied their noodles from Chinese people. We liked the way they thought about family. We liked that they called each other “Auntie” and “Uncle” just the way we did.

But they did not like us. They did not like the Chinese food trucks that appeared at our factories. They did not like the way we worked on Sundays. And on our side, though we liked them generally, we did not like their long lunches and their long vacations. We Chinese people did what it took to get the job done, after all. We felt they were more interested in play than in work. With the result that even now there are Italian people who will not hang out on the same cloud as us. If they see us sitting together, they will move away. And quietly, quietly, they will call us monkeys—very quietly, of course, because this is heaven and no one wants to be kicked out. We try to tell them, We never meant to take over your factories. And that is true. We cannot speak for the Chinese people who came after us. In fact, we do not even know them, a lot of them came from Wenzhou. But speaking for ourselves, we were just trying to solve a problem. If the American people had accepted coats that said “Made in China,” we would probably never think to look at a map to find out where Italy was—that is the truth.

But it is also true that my father is not here with us now because he just wanted to sell as many coats as possible. No one wants to pay for coats made one at a time, he said. He believed that the right way to make a coat was to make all the sleeves at once, and then all the lapels. He believed that the right way to cut cloth was the way that left the least waste, not the way that made the coat fall this way or that. He said no one was ever going to cut a coat on the bias in any factory he owned, and that he had learned about the market from the new village leader’s wife, who had a book about it. The difference between Chinese people and Italian people is that Italian people don’t want to listen, he said. They don’t want the world to change. But according to my father, the world had changed, like it or not. Price, he said, was king.

Maybe you can see how he ended up in hell with you, Mr. Nixon.

Up here in heaven, I do not have to do anything. But still, I like to draw coats. I guess that is just how we human beings are, we like to keep busy. I don’t know why your wife, Pat, hasn’t come to heaven. Maybe she is around here somewhere and I just haven’t seen her. I will keep an eye out.

In the meantime, now that I have met some saints, I know that you are not one. Indeed, I realize you are nothing like a saint at all. At the same time, you brought so many coats into our lives! Red coats, gold coats, orange coats, plum coats. Short coats, long coats, belted coats, quilted coats. You brought fur-trimmed coats and leather-trimmed coats, double-breasted coats and single-breasted coats, zip-up coats, and three-in-one coats. You brought coats people can wear in the snow and coats people can wear in the pouring rain. Even now I change my coat every day, and while I do not always wear a red coat, I never wear a dark blue coat, or a gray coat, or a black coat. I wore enough of those down on earth. Also, I use my English name. Do you know what that is? Tricia.

This is a heaven I never could have imagined. And so I thank you, Mr. Nixon. It is true that if I look down at China now and see the lights and the malls, I can still hear what people used to say about the Western way of life—that it is venal, that it is imperialist, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved