Ten Sleep

- eBook

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

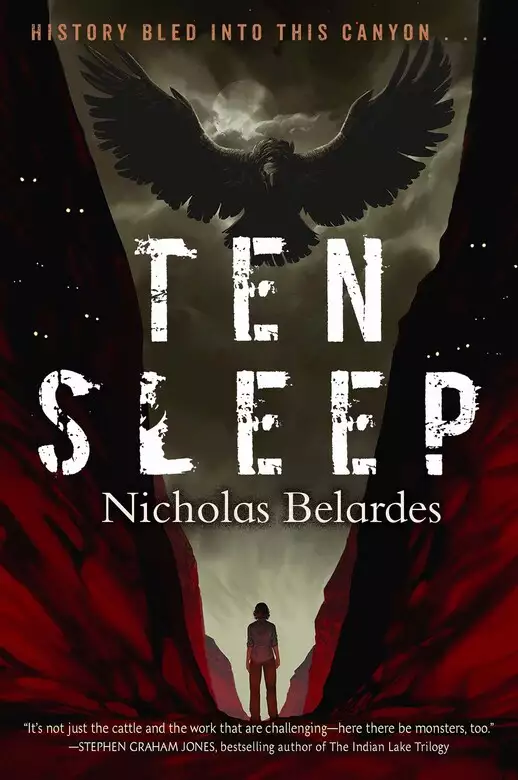

Jordan Peele's Nope meets True Grit in Nicholas Belardes’s Ten Sleep, a supernatural modern-day western about a trio of young people on a 10-day cattle drive that leads them through a canyon haunted by ancient mysteries and savage beasts who existed long before humankind.

A young Mexican American woman detects uncanny creatures stalking her on a cattle drive toward a canyon soaked in blood in an unforgettable novel, brilliantly infusing the modern Western with spine-chilling horror . . .

When Greta Molina’s old friend Tiller offered her the job, a ten-day cattle drive across the Wyoming prairie from the ranching town of Ten Sleep, it sounded like a well-paid break. Three hundred and twenty cows and calves, two guys her age she’s known since college, and a few long days on an ATV will give her time to sort out the mess in her head. The canyon along the trail has a history, sure, but nature has a tendency toward violence. Greta can accept that, even if it makes her insides squirm.

What Greta doesn’t know is the legacy of murder and rot that runs deep into the rocks of this land. As each night passes on the prairie, the trio faces mounting supernatural dangers: a ghost train of the damned, wild animals walking alongside dead ones—and evidence of a gigantic creature in the skies, one that’s supposedly been extinct for eons. And Tiller may be hiding even darker secrets the further they go. Safety is only ten sleeps away, but Greta soon realizes that may be too long for all of them to survive.

Nicholas Belardes’s Ten Sleep is a fresh portrayal of the American West for fans of Catriona Ward, Victor LaValle and Jordan Peele’s Nope, by a rising star in horror.

Release date: June 24, 2025

Publisher: Erewhon Books

Print pages: 288

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Ten Sleep

Nicholas Belardes

Prologue

Before you hear the stories of all those animals, that’s right, animals of the American West—some mysteriously reanimated, others consumed—and how they did or did not fight the mother canyon, or how they helped Greta Molina, because this really is her story, you’ll first need to know some “strange tidings” from a hundred or so years ago.

Good an entry point as any is what’s been hidden far longer than most been alive, and that’s what happened to two families of sheepherders caught in the wrong place at the wrong time, which was some decades after Wyoming Territory become inundated with cattlemen and railroads. Their tale of the high country isn’t always clear. But ain’t no recollection perfect, memory being what it is when telling the history of a thing.

Now, the Merrills and Johnsons were two strong sheepherder family names—and it’s tragic what happened to them squatters, although their misadventures are a pioneer story, and ironic in form for many reasons, foremost because they were unwanted white settlers targeted by none other than other white settlers, or in more specific terms, they were unwanted by those cattlemen who been in Wyoming decades before the Merrills and Johnsons set foot in that high country. Even so, take pity on these two families. Multiple members were taken and dogwhipped, then put on a long march led by the cattlemen’s hired gun Tom Horn—who was just as deadly while dead as he was when alive.

These families knew each other well. Come up from Missouri, though it wasn’t their intention to become late homesteaders. They weren’t altogether honest about what they done either. They run sheep in a joint-held corporation, which was their shared American dream, though they desperately needed grazing lands they didn’t have to pay for. Just before the turn of the twentieth century, this being sometime in the late 1890s, they bought land from one of those fly-by-night auctions set up in Laramie. Those acres were surveyed land the U.S. Government didn’t buy up, and those parcels in truth was confiscated from Indians and should have lawfully been kept under treaty, meaning that any way you look at this, those sheepherders were set to become occupiers, settler occupiers.

Come to find out, the land they purchased was surveyed from false maps, though not a single Merrill or Johnson could prove this in a court of law, being that both government and legislation throughout Wyoming was controlled by cattle barons. Though bought for less than $1.25 per acre, the land was in a sad state, drowning in swampland drainage from a series of wet years, and none of it was about to go dry. Homes couldn’t be built on such wet parcels, nor could any acreage be used for grazing or farmland, which the deal for all late homesteaders was to farm, not ranch, especially any sheep.

Near penniless and landless, both families believed they had to squat, to nest, so they could retain all their sheep. So they did just that, constructed homes on public land, which would become theirs after a number of years, and then ignoring the farming requirements, grazed their sheep on trails used by cattle barons, whose herds were funded by men from England and Scotland, which is to say, some folks wasn’t completely all-American as some thought.

Truth was, sheepherders purchasing unusable lots and then squatting in or near cattle country meant serious trouble to those cattlemen. Because they had to take care of the squatting, and that meant in their own manner of violence. And that was a bad way for them Merrills and Johnsons, because not only were they doomed from the outset, but by the very nature of being sheepherders, they fell outside the graces of cattle barons, whose gun-for-hire Tom Horn was nothing less than ruthless, him being a former Pinkerton man of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency and all. He’d once carried their card with the all-seeing eye that said “We never sleep” and helped capture and kill his fair share of outlaws. Don’t be fooled thinking he was a good man either. Horn, later a range detective, was the cattle barons’ “killer for hire,” and as a Pinkerton man he’d been allowed to murder more than rustlers, including those who held rights under former iterations of the Homestead Act.

The cattle barons, or cattlemen, having formed a

secret society of their own, retained Horn’s services both before and after he died. During his initial interview with his employers he said directly, “Killing men is my specialty and I seem to have cornered the market.” They heartily approved his application. Under their direction, Horn then continued to murder many a late homesteader, leaving notes or calling cards of rabbit or weasel pelts he’d hang from porches as a warning, that if not heeded, led to many a cold-blooded ambush. He’d hide in rocks, or in hills, in tangles of bushes, even up in trees, and would take his Model 1894 Winchester rifle, him being a former marksman for the U.S. Cavalry from the very posse that captured Geronimo, and would lay a bullet in the back of anyone lacking enough wits to heed his threats. He got to being feared, he did, perched on his black horse. That uncanny beast was large enough to fit his enormous frame, and though he tried to disguise himself as a bronco buster, would be seen away from any taming of horses. He sat like some kind of reaper, his mustache and hard demeanor and those piercing eyes half-hidden in shadow. All while that Winchester lay over the saddle horn ready to hurl its venom. Sometimes that sight was enough to scare anyone back from where they came.

Then, on July 15, 1901, Horn committed a murder he couldn’t squeeze himself out of, the shooting of the fourteen-year-old son of a sheepherder. Horn had closed a gate that was usually left open, hid among some boulders, and waited for the boy to get off his horse and unlatch the poles from loops of wire. No sooner was the boy done that Horn snuck a bullet into his liver from three hundred yards. Some, including an Indian of renown, said Horn could never have made that shot. But just because some famous old Apache said Horn didn’t do it, didn’t mean he didn’t.

Either way, Horn—reason being he either had the gift of gab or just couldn’t plain keep his mouth shut—confessed. Something he would not forget was the fact that not a single cattle baron would testify on his behalf, which would have likely spared him the noose. Stranger still was him not exposing a single one of them barons. Was soon after that a date was set for his execution—all his waiting for the noose passed like a short breath of wind. It was a cold fall day in November 1903 when he

got jerked to Jesus on the “Julian” gallows. But wait . . . While that flight to eternity was supposed to break his neck, he done cheated again, at least for a short while, because that son of a gun twitched a full seventeen minutes.

Horn had done more killing while alive than anyone ever thought, and that’s probably why his corpse eyes got a tinge of green like sea-foam. That and his hanged body, though it been in the ground five or so years, was needed by the same nameless and desperate cattlemen who hadn’t defended him, the very same men who’d stole a bit of magic from a certain canyon, a so-called mother canyon entity that they, meaning the cattlemen, would soon be contracted with for some mysterious reason or other. Said they needed Horn resurrected “not only to take care of our plan for the Merrills and Johnsons, but so that our pact with the canyon is set. She, meaning the canyon,” the cattlemen said, “is about to give birth and we gonna give her all the blood she requires.”

It was an elderly Civil War veteran turned cattlehand who pried the lid from a pine box at near two in the morning. Horn’s corpse mouth was still blue and bubbly. His eyes flicked like they wanted to come to life, like he’d turned all those nasty thoughts on himself but would soon be ready to turn them elsewhere. That was near to when one of the barons declared, “We need you, Horn. You hear me? We need you now more than ever.”

Horn’s dull green orbs stared, some say, like he’d been in a short coma with the yellow-green fever and not five years in the dirt, dug up during a dark moon. Always did have that midnight personality. They say his own hatred contributed to why his body hadn’t completely decomposed before he got dug up. Something in men like that never dies no matter how many times they been hanged. Still, that magic they gave him put some meat back on his bones, though not enough to make him any less rotten.

A little magic paste made from God-knows-what had been smeared on his tongue, though it could have been dripped like sap onto his corneas. Either way, that sorcery done woke him from his time crossing purgatory. No one knows what this magic was or is, or what it been made from, but there it was nonetheless, somehow bled straight from the earth, unexplained, old as the most ancient granite,

and learned by tricking both Indians and mother canyon—all of it stolen like them surveyed lands. The cattle barons said they’d stumbled upon this wizardry, something not seen in thousands of years, and in their own way, just like with anything, took it, held it, though they didn’t say they learned it in their own foul manner.

Anyhow, some cattle barons said Horn tore himself from that worm-eaten box, started pacing and ranting about like he was gonna get even, but then the cattlemen set loose what they’d planned, an apology for what they hadn’t done at his trial, which was to keep him alive. They said this was their way of making amends, gotta forgive us for what we done and all that, but damn if Horn didn’t still have a gift of gab, he started ranting that with this newfound energy, he might finish off all them cattlemen and settlers, who still been coming in wave after wave by wagons and rails. “I’m gonna be the new terror.” Horn coughed up some kind of bile-rot, then told them that’s just “the way it gonna be.” That was, until he winked with his one working eyelid and said, “As long as I’m still living, might even forgive the rope for being too tight.”

And so, the cattlemen, trying to rein in this living-dead man, and not tell him that he was again their pawn, explained to the corpse out of the sides of their mouths that in plotting their takeover of mother canyon, that this was a deal with her and it required sacrifice, but someone would have to do the murdering besides them. They told him outright that some cattlemen, Horn too, would be rewarded with the very thing them old conquistadores were after, eternal life; that there would also be some kind of return from the past in the form of monsters and other critters of darkness, not to mention other things raised from the dead; and that they needed to do this or the canyon, mother canyon, would unleash a kind of hell that even Horn couldn’t weather. They explained that with his help this could work—all of it. They could spare a number of cattle. They could definitely march these sheepherder families, and could see to it the canyon got what she required, or so they thought, could put man, woman, and child back inside her limestone guts as payment for a birthing she would unleash in a flood of blood and embryo, without killing them with her terror, or releasing it outside the canyon’s borderlands.

more self-important in his second go at living, told all them cattlemen in their midnight gathering at their meeting house in Greybull, every face lit by candle- and lamplight, his breath reeking of spoiled meat and fruit, that if they didn’t do him right, hell, even if they did do him right, he was gonna teach this canyon mother a thing or two and build an army of monsters and the dead of his own, and set them loose for no good reason on her, on Indians, on last homesteaders, and might include every politician in Washington, D.C., maybe every Mexican and Chinaman too, unless they came to his rally at the steps of the White House and listened to what he had to say . . . That was when the cattlemen told each other that maybe, just maybe, the hiring of this corpse might be a problem.

But that was too little, too late. Horn, dreaming of his army of the dead, tricked them just like he did that boy he murdered, and so went and worked for them cattle barons all over again, made them believe he was chock-full of servitude, though he wanted that magic to himself, yes he did, because after all, a monster loves a monster, and all monsters want to be king.

Horn though, he could lie when dead sure as he could while living, and acted like he was helping those cattle barons, who reminded him that the Merrills and Johnsons were their sacrifice, to which Horn agreed, not as the cattlemen leader—though he thought himself such secretly—but as their hired gun. He knew they were afraid of the law, afraid of him, that they feared this magic, though they wanted it, craved it, were trying to understand what eternal enchantments could do through such hocus-pocus, and assured themselves that it surely revolved around bargains with this mother canyon. And so, the cattlemen reminded Horn that she needed two families’ worth of offerings, though none of them cattlemen were a damn bit sure of what they were doing, or why so many sacrifices were required, having stolen, tortured, and killed for these secrets.

I say all this to not only remind you of Tom Horn being a ruthless monster. Or what them cattlemen done. Or of sheep, sheepherders, sheepboys, sheepgirls, sheep everyone eating up all the grasslands. You have to know this is a tale that includes murderous white folks who done their best to bleed the land and bend the will of mother canyon.

And so Horn and some of the cattlemen kidnapped the Merrills and Johnsons, burned homes, and threatened to sew closed some of their victims’ eyes, to tie their legs together too, and even have the children dragged. A man of no remorse, Horn said to these sheepherders, “Should never have come to Wyoming with your damn woollybacks. Now you gonna learn why.” It was around then he shorn the ears off Stewart Merrill and nailed that cartilage to a tree stump near a main trail as a warning to other sheepherders who might venture north.

It was an unseasonably warm late spring when both Merrills and Johnsons were marched for ten nights. By the end of that first day, feet blistered, eyes turned wild at Horn and his stink. They scraped their arms and legs crossing every rock, only being allowed to graze on day-old hard biscuits and dried meat, while the littlest Merrill sucked the remaining droplets of mama’s milk. Stewart Merrill’s wife was the mother of that baby, and that mother had a sickness, but tried her darnedest not to hack her lungs right there onto Stewart Jr., or in the dirt, and kept holding that infant tight, swallowing against her sore throat. Stewart himself could no longer hear, not with his head so wrapped, bloody, infected, earless. Their two daughters, Molly and Enola, eight and ten, helped their mother not pass out or fall again, and begged her not to crush the little one, and by the tenth night the ground grew so cold it burned their thighs. That was when little Stewart Jr. stopped moving altogether, his tiny corpse seemed more like something you’d lay under a tree as an offering for some bountiful crop or other.

The grandfather Johnson, along with Michael, his son Richard, his son’s wife Esther, their young ones, all tried not to complain, though it would be a lie to say they didn’t. Bernice, the youngest, resembled a tiny white imp that might about to leap from her mama’s arms. She had the devil eyes, not lying on this, she tried charming one of the cattlemen, who, fearing that little thing, made Esther cover the child’s face, saying, “Something wicked in that one worse than Tom Horn.

marchers howled like coyotes. But that stopped, all of that, just turned to grim determination, even in Bernice’s hidden devil eyes, because while the Johnsons’ wrists went raw in their rope ties, the family also sensed something besides malice in their captors, a kind of fear, a kind of pity, a kind of salvation along with that hint of devilry which had been said to them the first night by the corpse himself: “You know how long this gonna take? Ten nights. Just like when cattle get drove, or your damn sheep. We gonna get to know each other. Yes, we are. Ten sleeps are all you get.”

And Horn, he didn’t stop at that and gave a speech to them captives while they sipped water and fought over a remaining strip of bacon fat. Some say this was the biggest speech he ever gave, since he was used to his guns doing the talking, that something clicked in his head for once, something amid all that rot: that words could be a form of torture too, words that cattlemen often used, and he, of course, was and wasn’t in cahoots with the cattlemen, but sure hated every sheepherder there ever was, and might even use them in his army of the dead. Either way, he struck fear in them as their march was coming to a close:

“Someone told you to come take up this new country. Maybe those voices in your heads. Thought you knew the American dream, what it was to come start up all this sheepherding, while we done all the work for you winning over these grasslands, burying more Indians than stars in the sky. But you come to the wrong country, though you hold the Republic in your hearts. These United States ain’t but a map and a government that likes to eat fancy in Eastern hotels and restaurants. High-and-mighty politicians who don’t know a lick about grazing lands are the kind of men who fill your Capitol. And now you gonna see that it wasn’t America in your hearts after all, but cattlemen dreams you wanted to steal. You wanted all we had. And now that you can’t have any of it, whatever America you thought you knew gonna bleed right out of your mouths.”

Not a thing could stave the fear that every Merrill and Johnson felt at his words. Mothers tried to console each other and their children. They whispered to babies they would go home soon, have a nice supper, that everything would be fine. Said even the sheep was all fine too, though the adults knew every head of woollybacks been slaughtered like the culls that rid southern Wyoming of its swarms of jackrabbits and prairie dogs. Odd thing was, during one stretch of their march, bunch of coyotes howl-yipped as if them dogcritters believed what the cattlemen been saying since long before statehood: “You and your plague of sheep been poisoning this land.”

During the earliest part of that tenth night, every Merrill and Johnson been blindfolded, roped together. Some of the men were even gagged after the cattlemen said, “Y’all just won’t shut up, ever, will ya? Where you plotting to run off to?” And that was enough to also sew William Johnson’s eyelids shut, and for the women and children to talk only in low whispers, to wipe the now-blind man’s bloody lids.

Eventually all went quiet except for the whinny of horses, and that endless coyote yip-cry on dusk-lit prairie winds, not to mention teeth chattering around night fires. And everyone, even the babes, thought about ghosts . . . and Tom Horn looked like he’d die again at any moment, incisors dropping from his gummy mouth along the trail.

And soon, well, that very night, they all stood at the entrance to that mother canyon, ghosts welcoming them inside, and Horn smiled through those yellow-green eyes. And then he revealed his new intentions, that he didn’t want to only raise an army of the dead. “This place gonna make me young again. Then I gonna live forever and run for president.”

Now listen, I got to tell you these other things before I get back to that tenth sleep, that forever sleep, okay? Mother canyon might not recall everything, but it’s fair to say she remembers every drop of blood ever spilled. There’s murder in the rocks. Murder on their granite surfaces. Inside too, in the belly of cold volcanic fury, in every pyroclastic or granite pebble, and every rising pinnacle of limestone. In any mineral thereabouts too, and that rock that formed from mineral sediment so long ago where life itself was ancient, primitive, got killed and remembered. More kiss

of death in them than any rock imaginable, where every grain becomes a skeletal fragment. Every coral or ooid or limeclast in them, or string of algae, or brachiopod skeletal micrograin, or tube worm or planktonic foraminifer, and so many, countless countless, because them’s in even the tiniest of fecal pellets shit by marine organisms, god knows what exactly, but those organisms surely murdered, and murdered again, and were murdered, forming entire canyons reeking death and shit and blood, everything compacted into carbonate sediment, and deep inside, so much acid burned at the violence that caverns formed, vast and empty, sometimes with openings to the earth, with air trapped that ain’t been breathed since a hundred trillion other exterminations took place, creatures screaming in agony, creatures no white settler or Indian ever knew, or could know of, they could only feel that the canyon knew, her intent, her burn, thoughts like acid, in need of sacrifice, because she was to give birth. And it wasn’t ever fair. In no way was the mother canyon being right or just, but she took, so that she wouldn’t unleash homicide on the scale of limestone formation, that claustrophobic crush and mineralization, or volcanic formation, or any geologic upheaval into the bloodstream of the world, that epic slice of organic life that had to go back into the land, grain by grain, cell by cell. And then come to find out that every hundred years or so she went through this, you never knew the exact time frame, and that she, mother canyon, demanded blood payment, though she didn’t always used to. And her terrors ate and devoured, though was hardly seen, and could be born again and again.

And Horn didn’t really understand this, nor did the cattlemen, not yet, and definitely not the Merrills or Johnsons. They didn’t realize a thing until after that tenth sleep, when they woke inside the canyon to all those eyes, animal eyes, bird eyes, dog eyes, lizard eyes, dead eyes, living eyes, though every eye was one or the other, or wasn’t, because there were hides that rippled, and wings spread, and those legs moved, and teeth gnashed, and they were things that no one had ever seen.

That night Stewart Merrill’s wife was glad her baby already died. And that devil child, Bernice—a charmed cattleman took and spared her and she fled with pockets full of magic.

And the rest of those Merrills and Johnsons, they

got their ropes cut from their hands, but there was nowhere they could run, not from this, not from mother canyon.

The cattlemen soon retreated, yes they did sure as a gun has bullets, unsatisfied with their new bond because not a single one of them figured out how to live forever besides what they done to Tom Horn. Afterward, they could see that mother canyon had retreated into herself, and knew she would lie dormant for a time, long enough for some of them to pass on what they thought they knew, and what they done to Horn, and wouldn’t do to themselves—to make creatures and men live long after cattlemen gone and died—though there ain’t been an undead man or woman roaming Ten Sleep in fifty, maybe sixty years. Cattlemen, they say, just don’t like seeing their grannies with dead-alive eyes.

One day, however, they hoped to learn something new, that maybe the time would come that not too many would have to die to make the magic work, to appease the mother canyon. But that’s what this story is about, and you’ll have to read on to discover any truth . . .

Horn, however, deserves another mention. Bent on betrayal of everyone and everything he could think of, especially since he’d been betrayed too, Horn went right up to them creatures and rocks to demand of mother canyon that his new eternal life make him king of the canyon, that all of this should now be part of his army.

Been written in cattlemen’s logs, and in a few other portions of this story, that this was when Horn lost his head for good, that something fierce took it clean off, making it evident that he would never be president.

Some say, if you were to return and put your ear to the cold lips of his decapitated head, he might whisper different. That is, if you can find his head at all.

Many decades passed since the canyon massacre, an atrocity that no one outside of cattlemen and cattle barons had even known. But I gotta say as you enter Greta’s story, and the stories of all them animals, that mother canyon has already begun her transformation in ways even she never intended or could foresee.

Blood is again required.

The calf dragged behind Greta’s Yamaha quad and all she could think about was bones.

Cow bones. Human bones. Bones beneath all that sinew and skin, and how many. Both, two hundred and six. Dogs and cats have dozens more. Birds, twenty-five if they’re lucky. Cattle have the same number as people, as her, she thought, under all that black hair tied up tight, her pierced skin slightly darker than her dad’s tatted Mexican American arms ever were. Much darker than Hannah though, whose hair was blacker than moonless nights, who’d been missing for months, though not officially. And this was all gruesome to think about with the dead calf’s hind legs roped to the quad, dirty head full of weeds, blood no longer flowing, lungs no longer crying for its mother, bones no longer doing anything, all two hundred and six of them.

Twenty minutes ago the month-old calf dropped dead. That’s what Tiller told her. The trail boss who’d hired Greta and Scott, Tiller had been driving the main black-and-white mass of herd across a sea of green and gold, working his quad slowly back and forth, pushing the cattle through prairie and sage, making for distant limestone canyons—still many miles off. This was all part of that grazing ecosystem—that balance between what was profitable and what was best for the land. Not to mention, they had other grazing grounds where this bunch could be made fat and happy, and a proper milking facility. Before that, Tiller had given Greta and Scott the same herding instructions he’d bestowed on them a million times: “Look, this is the way herding goes . . . move slow, some stop to eat, some stray, they advance like a small army, an infestation, eating grass and whatnot, scaring away some critters, attracting others. When animals do what you want, back off on your quad . . . and I don’t want to hear anything about a horse being more maneuverable.”

And, yeah, that had been the gist of it, the day starting off at the pens outside Ten Sleep, Scott belting out the cattle call that Tiller taught him, Come on–come on–come on! with hay bundled to the back of his quad to get them following some kind of prize, funneled out of the pens and on the march. And then, miles later, they didn’t use that hay but pushed the herd down the trail, triangulating them with their quads and catching strays, moving the mass of complaints and hoof-strikes eastward with the sounds of their engines.

And then Tiller about that dead calf: “Critter fell like her thin legs were done holding all that weight. Just couldn’t take whatever was eating at her.”

“That why you came and got me?” Greta adjusted her ponytail, shifted her hips against the quad where she leaned, goggles around her neck. “Poor thing’s buzzard meat.”

Greta had been creeping along the cattle’s western flank, goggles on but not her helmet, whoops, ponytail flipping behind her, the breeze ripe with pollen, Greta trying to get a troublesome heifer to keep up. The wide, stumpy bovine, shorter-legged than any other cow, had been enamored with some of the wildgrass amid nearby rocks and a gully of cottonwoods, always wanting to eat where she shouldn’t, always wanting to stuff herself even with some of the wildflowers—buttercups and clover around this patch—to chew, regurgitate, chew some more. Greta hadn’t eaten lunch, had spent so much time with that bovine, driving over cowshit mounded in the grass. “I’m going to move you”—she nearly poked the beast in a wet black eye—“and then you know what? It’s going to be my turn to eat.” More than anything, Greta wanted to slap that mess of fur in her hindquarters, get her going. But that could have startled her, made her run the opposite way from the main group eating its way west across the high country. She’d nearly got her interested in rejoining the herd when Tiller called Greta over.

The cow quickly trotted back out to a tasty outcropping of thick emerald stalks.

“You just let the most persnickety cow get her way,” Greta complained. “That heifer’s gonna eat herself down to Dallas.”

“Or up to Billings,” Tiller said without cracking any kind of smile. The sun in his face made his eyes squint nearly closed. “Need you to drag a carcass a mile or so back to the main trail and call the renderer. Wait for him and get a receipt. Don’t want any accusations of leaving dead cattle.”

“Drag?” Greta eyed a lump of hide in the distant

prairie grass. “That’s a goddam delight. Carrion eaters just waiting for that veal.”

“Problem is,” Tiller went on, ignoring her, “as you know, phones don’t work on this stretch. Gotta head back over that eastern slope, back down to a connection.” He wiped his nose with a handkerchief. “Come on with your quad. I’ll tie her up.”

Greta had known Tiller on and off for several years but still wanted to poke him in his skinny chest for not listening. Why didn’t he get that she needed to win out over that wandering cow, chase her down again and teach her a lesson, else the creature would get the best of her. Greta swatted at a cloud of gnats. “I need to move that cow right now.” She plopped a remaining bite of jerky from her pocket in her mouth like a prize. “She’s going to end up lost in a ditch.”

Tiller wasn’t having it. “I’m telling you to drag that calf.” He scratched at one of the scars near his chin then drove over to the dead calf, not even checking to see if Greta trailed him, which she did.

Greta parked on a dry patch of grass, still positive nature could take care of the corpse, she was sure as anything about that. Flies were already licking at its snot, laying their maggot eggs. “Just who are you wanting me to call?” she asked.

“The dead truck—the renderer.” Tiller had already begun winding the calf’s hind legs together, leaving a stretch of rope to tie to Greta’s quad. “He got a deal now with the ranchers,” he said. “Free pickup for dead livestock. He’ll come winch the critter into his truck, take the remains to a compost facility.”

“Why not all the way back to Ten Sleep? Your dad might wanna turn her into taxidermy. Make her into a little milk shrine.” She liked joking but truth was she didn’t want to pull that thing ten feet, let alone all the way back to the edge of town where Tiller’s dad, Bobby, gutted every living thing imaginable, then made that into corpse art.

Tiller lifted his hat, wiped across his head. Greta knew it wasn’t in Tiller’s nature to laugh, but he nearly did. “He would,” he said, as she cracked a smile.

At the same time none of this seemed good at all. Being ground to meat pellets in a facility sure would be a gross way to end up. And

the idea of pulling that carcass? Last thing she wanted was to sound like she couldn’t do her job. But dragging it a couple miles or more made her insides squirm. She couldn’t admit that to Tiller while she copied the number off his phone, like she also couldn’t admit this brought back a particularly messy memory, that after her dad collapsed a few weeks ago, when he weighed all of a hundred and eleven pounds, she saw him being dragged worse than this calf.

Cancer had been eating at her old man for the better part of two years. He could hardly walk or breathe, was no longer Gabriel “The Pope” Molina, badass Mexican American truck driver, gun-toter in a black Stetson barreling down highways, picking bar fights just because the pool tables were full, or ordering her and her mother around simply because he thought he could. He’d become a shell, a whisperer, a mutterer. There’d been something both good and tragic in that transition, not having to listen to him butt heads with everyone in the room. There were some parts of him she missed, because she did sometimes love the way he was, the way his voice could lower a notch when he’d say, “Mija, you know I love you.” The way he could protect her and taught her to protect herself. And the way he understood the outdoors. He was the first to teach her anything about animals, the misery of nature, the fact that every living thing had to fight for survival. She’d seen it in birds, bears, prairie dogs, coyotes, mule deer, you name it. Sure, there was an order to things. Didn’t change the fact that nature had a tendency towards violence, and that made her wonder what would happen to her at the end of everything, even though she’d grown to accept the possibilities. At least she hadn’t cried like when she was a little girl and would see a skunk or a possum dead on the side of the road. That kind of loneliness destroyed her insides when she thought about being something small and injured, then abandoned like that. She’d seen a coyote swallow a rabbit in three chews, a bear gnaw on bison ribs, and bovines murdered like the calf, dead and staring. And she remembered sleepless nights, having seen so much death while her old man pointed out each instance, including that gory bison corpse in Yellowstone: “Look mija, that bear is hungry, hungry. You don’t wanna be no buffalo today.”

Her dad died much slower than something on the

side of the road or in the prairie. He started living inside himself, having slipped into his own memories, and she and her mom knew he was never going to return. Sometimes he would groan and stare, sometimes laugh to himself, sometimes string words together like he might remember there’d been love in the world. The afternoon he died, he collapsed on the lawn, legs twisted under him. Greta had just rolled up in her maroon hand-me-down Subaru, metalcore blasting from blown speakers, as her mom, like a hungry creature in some slow-motion film frames, dragged his rubbery corpse by one arm across weeds and dirt. Greta turned off both the car and the radio, and her mom said, teeth grinding, breathing heavy: “Don’t want your father out in the sun attracting flies . . . Just fell . . . Told him to stay inside today . . . Didn’t listen.”

Greta couldn’t do anything but sit there watching, didn’t offer to help at all. She saw her father’s head bend back like a rubbery wet stick covered in mud and that dirty brown eye stared back.

So she grunted at Tiller, didn’t say what she wanted to say, because last thing she ever wanted was to drag a corpse, and she probably shouldn’t have brought up that bit about taxidermy and Tiller’s strange-as-hell dad.

She was older now, mature, yeah? It wasn’t like she didn’t know animals died. She’d driven a few cattle before dropping out of college, occasionally helping move herds near Laramie. But those were only a few dozen cattle over several miles—from one small pen to another. Fifty bucks and free meals. Those days were fun. She laughed a lot, flirted more. She was dating Hannah then, had someone to look forward to no matter what dumb side job she had. They’d seen each for the first time at the Lope, a bar in Laramie, though they weren’t on a date, just strangers making eye contact. They met for the first time outside Greta’s apartment, Hannah standing beneath Greta’s window, smoking. That led to a date, and another, and so on . . . She felt confident those days, beautiful and all that. Not like now with all these heartbreak blues still haunting her, lips all cracked in the sun and wind. She felt like a tomboy, tomgirl, plain, broken, all that shit that she didn’t want to think about.

But Greta wasn’t so laugh-happy anymore, not about

about any job. Since abandoning UW two years ago she mostly waitressed, other jobs too, fed horses and goats, cleaned windows with drones, drove a Red Bull car until she crashed it—hadn’t told a soul she’d been drunk—just hopped gig to gig after, always hungry for extra cash, for a way to stop dragging her own dead weight. Nothing happy about any of that, really. She knew she made choices that others might not. Those were about all she had, choices not to screw things up, even a simple job like this with a couple old friends. So she had to have this money. She would use it to gas up and get the hell out. Whether or not she’d chase down Hannah—if she was chaseable—or just go work somewhere else, well, maybe this drive would help with all that.

Good thing was, this drive was different than any other. Greta thought it could take her mind off things. A thousand bucks to help move about three hundred and twenty dairy cattle, including ten or so calves, over sixty miles or so to a distant ranch or grazing grounds, she wasn’t sure where exactly. Somewhere deep in Bighorn Canyon country, with gas caches stored along the way for the ATVs. No idea why there weren’t enough paved roads in this day and age.

Seeing a dead calf wasn’t enough to ruin her day. Not that dead things necessarily grossed her out anymore, okay they did, but worse was the tying up of this dead thing that made her uneasy, as if its spirit, or whatever soul-thing it had, was still swirling in its innards, and couldn’t be set free, and that felt like some kind of prison that something dead didn’t deserve. Death makes an idiot out of everyone, she thought, as if no one can really play the part, so she promised herself right then she’d never die like that calf and get dragged. And then she imagined herself an old woman and kind of hated and loved the idea all at once.

She stared at the calf’s dead brown eye. A line of clear snot bubbled from its nose. “You can’t send Scott?” she asked Tiller. She wasn’t giving up on this just yet.

“He’s a quarter mile away,” Tiller said. “Consider this your second test.”

She almost laughed at that. “What happened to my first?”

“You couldn’t get that cow back into the herd.”

How many days you need for that?” he asked. “Look, carcass gonna draw predators sure as anything and that could lead to killing,” he went on. “Calves drop dead sometimes, you know that. Your quad can handle dragging her. She was only a month or so old, barely a hundred pounds. And Scott’s busy moving the herd in case the prairie grass around there went toxic.”

“I can move the herd.”

“Whatever, Greta Molina.” He said her name with a kind of finality, which she hated, like she was still the same half-Mexican American girl he gave a hard time to before she dropped out of school.

He finished tying the rope to the back of the quad.

She knew right then that was that, she’d have to pull the body.

Though she hadn’t seen Tiller in at least a year, he seemed harder, especially so right then, like he’d gone through something he hadn’t told any of his friends. He had one scar over his left eye that hadn’t been there before, almost like a burn, and another on his lower cheek. She had the sudden thought that a single claw had tried to scoop out his eye and then nicked his cheek. She noticed a limp he’d never had too, like a part of his left foot had gone missing down the throat of a wolf. He’d been emotionally cold even back when they were in college, that was just his personality, though maybe something had happened to further harden his demeanor, something with those wounds, and if she was seeing straight, with his thinning hair. That monotone voice had always been there. The lack of a grin too, and he never hugged, ever. Never seemed excited to be around anyone. She always brushed that off as him being a loner like her, and, well, a little weird, more than her anyway. Some towns and people around here made you that way whether you liked it or not.

She was hopeful about one thing. He used to loosen up some when he drank, especially if he downed more than everyone in the room. He liked that. It was stupid, but he did, made him kinder, she remembered. She recalled an innocence about him when he was drunk, like he really was a kid inside. For a time that counted for something. Back then she even thought Hannah liked him. She stupidly remembered that maybe she liked him too. One night they even made out, kind of, not really.

She’d been such a jerk afterward, keeping her distance. It was just that the kiss had been off, maybe that whole night had, and she’d done it to make Hannah jealous, and though Hannah said she forgave her, maybe she didn’t. She knew she shouldn’t have ever slipped. But when you’re at a bar, buzzed, and mad at your girlfriend about something stupid, well, it was one of those nights at the Lope that should be forgotten.

All those times doing things they shouldn’t have, crossing other boundaries they never should have. Hell, even Tiller’s narrow-set eyes and long face seemed cute in that neon bar light, almost normal in the moment. When they kissed, when she leaned over to kiss him, she instantly pulled away, realized she could find a hundred times more affection in a farm dog, the kind that don’t do a thing except lay there and stare at chickens and big white manky mallards named Wingy and Ducklin’ all day. And he saw that realization in her eyes, had to, yeah? There’d been no hiding it. And that was unfair, made her a jerk, the fact that she couldn’t hide how gross she felt at the time.

And Hannah never cared enough, though maybe she did, that was the problem, maybe what made her leave, though Greta didn’t really know. Hannah had even said to Greta’s face, “I just don’t care about anything anymore.” And Greta remembered taking that personal, and then Hannah saying, “I didn’t mean it like that,” though her eyes kind of betrayed her. And then, because memories all blend together anymore, Greta recalled Hannah disappeared soon after that. Three years together and she just split. Ghosted. Months later and Greta still go’ogled obituaries. And hell no, she wasn’t about to ever read her dad’s obit. She skipped his funeral altogether. Had to.

Greta and Tiller kept on as distant friends for a while after her flopped makeout, and in a way that surprised her—that they kept any connection at all. He kept on acting like the same cold tap water. Like television static that once filled screens at midnight. And he even was a bit kind when drunk. Or had she remembered

wrong? But their distance grew. Pretty soon she stopped seeing him around. He took to working for his family. Grandma’s cattle. His dad’s taxidermy. And then he disappeared from Greta’s life. Until now, until this cattle drive.

Something about those past days between her and Tiller had struck her while she drove to Ten Sleep: You forgive your friends, forgive their weirdness, forgive not knowing who they really are.

Then there was that other thing: You need to forgive yourself. She knew that. She also knew she was a long way from that kind of self-repair, from letting go of that hot flash of pain still deep from her mess-ups, and Hannah’s recent disappearance, and from when Greta refused to help Mom drag the Pope up the stairs to the porch. And then skipping the funeral, yeah, she was a long way from just being happy with things, with processing, with moving on in her present, toward that shiny future that now seemed dull, waxy. She thought maybe it was fading altogether.

When Tiller phoned her out of the blue a week ago, he acted like no time had passed, like their distance had never existed, like they’d just had that ridiculous kiss she could still taste as if something dry and dead had lodged itself in the back of her mouth. He didn’t ask how she’d been, instead straightaway wondered if she was available to help drive the herd. And he said it like that too, “I was wonderin’ . . .” And that was that. She didn’t even ask about the pay. She needed the money, any money. And surely this would pay more than serving at the Ribs N Go.

And now here she was hauling a dead thing, dead like her dreams, the way she sometimes could imagine Hannah dying over and over, though she thought Hannah wasn’t dead at all, couldn’t be. This deceased same-number-of-bones-as-a-human thing.

She throttled at a slow pace through prairie grass and over ruts, even animal burrows to the anger of everything living beneath. Even the nearby prairie dog town raised its collective fur in an uproar at the macabre parade

float, barking and complaining at her, some of their dog bones strewn in the dirt, maybe killed by a bobcat, while a flock of curlews sailed low over the grasslands, calling like scared sky-dogs.

Greta got to pulling the calf faster than she should, in a hurry now along a fenceline to call the dead truck to get rid of the thing. Then she cut across a curve, straight into open prairie to try to save time. It was bumpier here. She didn’t care and hauled ass.

She started thinking about the time she busted a wrist leaping off a rope swing. She remembered how the Pope had told her to stop being so damn reckless, but she just swung higher and higher, then flew like some kind of crow, black and diving and twisting through the air. Sure, every kid was stupid at one time or another. She’d leapt from where the swing had been mounted to an oak, tried to get to the moon, a mooncrow taking flight, thinking maybe she could escape gravity. She somersaulted onto her own outstretched hand, came down hard on a root. Then came a snap, then hopping up to see the lump that formed under the skin of her wrist. The bone, crunched and jagged, somehow hadn’t broken through. She hated that feeling of knowing how broken you could be inside, the shock of knowing how it really was.

Prairie grass soon morphed into repeating memory while she pulled the calf, her family’s double-wide trailer somehow transported to the ochre horizon, her forearm floating at an unnatural angle, the young version of herself making her way to their front door, hoping a whooping wasn’t waiting just inside the foyer. It was. The Pope, having heard her yelp, was just about to wreck her world, grab her by her collar while her unsupported wrist bones ground and jiggled, trying to break free and spill their marrow.

She thought about that door, that thin barrier between safety and hell, how much she’d dreaded stepping through. It seemed to breathe there in front of her even now, like she could shut off the quad, sneak through to the past. That girl she imagined just stood there, not even crying, arm bent like a snapped broom and wrapped in plastic. She started to think what she’d say to her, how she’d tell her not to be afraid, that the Pope was a temporary shadow, that he’d get dragged across the lawn one day like a dead calf behind an ATV. That middle-aged man so strong then, arms

like pipes, finger-vices ready to grip, that black-and-grey beard, the glistening macho earring like the piercings in her eyebrows, eyes like garnets, that godlike baritone voice.

Then her vision shook loose. The ATV’s rear left tire slipped into a rut, then a deep hole. The sequence nearly jerked her from the seat when she hit the brakes, and then it was like time stretched itself into infinite uncertainty, a starry hole beneath the quad that could swallow her and the ATV, the calf too.

Fear rose in her throat as the quad jolted to a stop.

She glanced at the stuck, sunken tire. Farther back, a cloud of dirt and fur swirled and faded above the calf.

Moving along this kind of territory was always a stop-and-go thing. Never knew when a tire might slip into a badger den, a hidden prairie dog’s sunken town hall or a ditch. Either way, she was now annoyed on top of being annoyed. She didn’t want to jump out too fast or the calf’s dead weight might jerk the whole quad back on her, then she’d be stuck under the machine with no one to help. She didn’t want to untie the calf from the quad and have to retie it, though she knew it might come to that. Better to just throttle slow and steady.

She gave a twist. This rocked the quad forward, sunk the trapped wheel deeper, putting her even more off-balance.

“Goddam it!” she barked. “Scott should be the one doing this.” She pulled up her goggles, shook her head—she couldn’t be mad at Scott. But, Tiller. Yeah.

“Hell with it,” she said and throttled hard, spinning tires, kicking dirt. The exhaust let out a groan along with the sound of ripping and tearing. The ATV jumped right out of the hole. When it did, the rope jerked on the calf and nearly flipped the quad. Strips of tire flew past. The off-balance quad wrenched at such an odd angle that she killed the engine and jumped off.

A shredded mess of rubber covered the ground and axle. Now stuck with a homemade three-wheeler and a calf about to bloat, she pulled off her gloves and checked her phone. Still no cell signal.

She examined the hole, a cut in the earth like

something wanted out rather than in. A rusted finger of metal poked from the dirt, having been lodged there a hundred years ago, maybe more. Didn’t know what it was, and wasn’t about to pull on it or give a kick, the damage had already been done. She just let it protrude like a digit, expecting a metal hand under the earth to pull it back underground someday.

After untying the rope from the quad, she walked over to the carcass. The poor thing lay covered in dirt, weeds, flies, and butterflies slowly flapping pale grey-blue wings. If she’d pulled the carcass over the rut that metal might have split the calf wide open.

“Should I just leave you?” she said, thinking maybe she should have untied it anyway. “Who cares if some coyotes get a free snack?”

She knelt down, not knowing really why, maybe out of sadness that a thing could be so fragile. A wood tick crawled along the calf’s white eyelid. Others crept through fur, easily seen in white hair or on pink skin, engorged and blue. One hung on the cow’s lip, waiting for Greta to move closer.

She felt bad for the calf, stared again at its dead eye, flicked off the tick. “What would you do?” she said. She could inch along to the trail on three wheels, though she might break her neck in the process. She could just lie about everything, limp her quad back to the herd and say she called the dead truck. She doubted if Tiller even brought a spare. Didn’t remember seeing one strapped anywhere.

“I can’t pull you like this,” she said, not liking either choice.

She decided on a third idea and started walking.

A wind kicked up, whooshing and scratching among grasses, rattling seeds and more pollen, making all kinds of strange noises that Greta hadn’t heard over her quad engine. Prairie grass moved like undulating cilia, as if the world hung upside down, could crawl away on grassy legs if you somehow flipped it over. If only she could, she thought.

Some of the land here had formed more than a billion years ago. She knew that, had read about it. While she’d dropped out of the bullshit scam of college and its loan system, she hadn’t abandoned learning. She wasn’t too shy to check out a library book, and hoarded a personal collection built from one of those little

neighborhood libraries run by retired UW biology professor J.A. Maynard. He was always shoving bird guides, novels, even geology books in her hand. “Study this one. There’s life all around you, even in the bedrock,” he’d say. “You need to understand, Greta, just how fragile this old world has been.” That’s how she knew about nature writers like Sibley, Lee, Lopez, and McPhee, and more novelists than she cared to admit. Because of Maynard she knew that distant towering canyons had been carved from shale deposits of Precambrian sediment. They held beads of fossilized algae, some of the planet’s earliest known life. She’d read about the end of the world for dinosaurs, fossils found at the asteroid strike, a skin-covered Thescelosaurus limb torn at the Tanis fossil site in North Dakota, entombed on an awful day sixty-six million years ago. Fish too that had breathed impact debris. Funny how all of that generated new microbial ecosystems. Subterranean nurseries beneath crater floors, leaking right through rocks fractured by the impact event.

She dreamed of wandering those cliffs, discovering fossils, stumbling into fame for her discoveries, if anyone could be famous for finding anything. Though she would never name anything after herself, that was stupid and one hundred percent ego. She dreamed of the prairie too, those long loping swells, the yellow and green folds, its topography frozen in time, covered with grasses here, sage, coyote, and other brush in other places, all on a land so time-forgotten that Greta thought not even the rocks and dirt beneath could remember where they came from.

The ground sloped upwards here, making the trail in the distance hard for her to find with the naked eye. But with distant rises like purple shadows on the afternoon horizon, she knew where she had to go. Tenth of a mile, quarter mile, didn’t matter how much farther—eventually she’d run into the trail.

She trudged up a long slope, down another, and over two more low rolls in the earth, peeking back in the direction of her quad until she couldn’t see it anymore. Wasn’t like anyone was going to run off with the machinery, though not seeing it made her uneasy. Sure would be a long walk back if she couldn’t get a lift with a spare.

The main trail, just over a final slope, came into

view. She could see the path stretch far into the grasslands, parallel to sage-covered slopes. Eventually, she knew it turned into a canyon route up past Tiller and Scott, but not for many miles yet.

Her phone now showed one bar—enough to call the dead truck. Starting to punch in the number, she stopped and gazed in the general direction of her quad and saw what seemed a large raptor sweeping low over grasslands, too big to be a vulture. This was the third or fourth she’d noticed, though this bird was the largest she’d seen for sure, probably ever.

Something about its wings she could tell was different—thicker, wider wing tips, long primaries like distorted skinny-fingered hands, maybe some kind of white pattern in the underwings when the bird started to roll away to its right. The angle of its flight was different too, something was off, she could tell.

She’d seen a lot of birds through the afternoon, raptors mostly, hawks and falcons, a few buzzards too, along with the occasional sparrow, a blackbird swarm, several thrashers, a few towhees, too many meadowlarks to count singing along the fences and rattling their exultations in the grass. Sometimes ducks and more curlews flew over, including a lone male Wood Duck. She wondered if she’d ever seen such a duck, maybe? Half the time she could never tell a duck species like Maynard could. They all looked like mallards to her, though some were clearly smaller. This raptor would surely bring others, she thought, the thing having likely sniffed the dead calf on the breeze. What had Maynard told her once? Species with similar shapes usually have similar habits. She hated when his voice popped in her head. Better than the Pope when he was mad, though she missed Hannah’s soothing whispers. She loathed those fragments of echoes the way she loathed that calf and doing all this walking.

This bird must have been more distant than she thought. Heat shimmered off its wings through the afternoon daylight. Its mostly black wings didn’t beat at all, just glided, cut through the landscape, soared like it owned the wind. Then the bird dropped beneath one of the low slopes, and if she wasn’t mistaken, somewhere around the quad area, though that didn’t seem right, maybe far past it? But then,

what if it was past that point? Would it be that large? Sad thing if that carcass got half eaten by a swarm of carrion eaters by the time the rendering truck reached it, then why bother calling?

A moment later the bird’s black form shot upwards with big floppy wingbeats. At first she thought a jackrabbit might have been swept into its talons. Then she realized this was too big to be a rabbit, had to be something bigger. And this bird. It was large all right, eagle sized, no, condor large, jumbo bird sized for sure, though there hadn’t been a condor around these parts since Maynard stopped her at his outdoor book kiosk to tell her that Condor 832 had been discovered at the highest point in the Snowy Mountains, that Maynard had seen photos taken of the thing perched atop a rock. She didn’t care much at the time, just went on listening. “It was up on Medicine Bow Peak,” he said like she’d hungered for every detail. “Disturbingly at peace, staring down at Lookout Lake.”

“You know, I just want something to read, something I can escape with,” she told him at the time. “Something I can curl up to with a hot dog and a beer.”

Identifying tags on its wings had marked it, he said. T-2. Condor 832. Spit flew from his old lips like he was giving a lecture. “Furthest north a bird like this could usually be seen was Utah. Not this girl. She’s been on a five-hundred-mile carrion bender, burning through the American West, ripping through every carcass she could dig her sharp bill into.”

Sure as hell, that condor was found dead a few days later near Laramie, probably from eating a dead coyote or deer shot with lead bullets. Another sad story, Greta thought when she ran into Maynard again. Another sad life. That day he handed her a book on ice floes in the arctic. She tried to tell him she didn’t care about ice floes, calving, or how thin polar bears got from lack of food these days. She then wandered off with the book anyway, thinking about big dead stupid birds.

But this bird almost seemed double condor-sized. Almost, because no bird could grow that large, could it? And if it was—because it seemed like a small plane racing over the grassland—then whatever was in those talons was larger, much larger than a jackrabbit, meaning that birdplane had dug into that calf. This sent a chill from Greta’s stomach into her throat, even into her thighs and arms. She tried to swallow.

jumbo condors. If this was such a bird, it would have feasted right there, broke through hide, ripped out organs and meat, chowed like Condor 832 did in her glory days. Whatever this was, if it really was carrying that corpse, then it held on like it was nothing—which meant its wingspan was twice that of any condor.

Her chill continued, freezing up her shoulders and legs as if an ice wind were blowing from an invisible glacier, even though logic told her that sometimes in the prairie maybe you see what you wanna see. Hell, maybe that ambulance that

carried her old man’s corpse had been a big metal hog that swallowed him whole. Whatever this was, she felt for that calf like it had been a friend killed out on the dirt. She felt all wrapped up in its hide, that pink skin and sweet dead face, then wished she’d buried the thing, that she’d done something besides walked away to where she was now.

The prairie surrounding her seemed both bigger and smaller all of a sudden, like things even a thousand feet in the sky were watching, could close in any second, like she could run forever and not escape her own nightmares, that even the sky and distant cliffs would eventually press in. Even these grasslands left her feeling on edge, like they might rise up, even in daylight, stuff her mouth full until she choked, that maybe all of this was gonna take her and pin her to that rusted spike that tore her tire to shreds.

She thought all this and watched that bird flap those long wings until it fused into a speck that disappeared into the haze of coming dusk. A moment later, still feeling watched, still chilled, she figured to hell with the dead truck and started walking back to town for that spare and a ride.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...