“Creamy Earl Grey.”

“Darjeeling.”

“English breakfast.”

“Darjeeling. Doesn’t the name say it all? The romance of travel. Misty hillsides and light, warm rain. Green plants and fragrant leaves.”

“We’re drinking tea, not writing a novel, Bernie.”

“I like to think I can do both. At the same time.”

“Very well. Two Darjeeling, please, Cheryl.”

“You could have ordered a pot each, you know,” the waitress said as she went to place the order.

My friend and I grinned at each other. “You sure you want to do this?” I asked her.

“Drink tea?” she replied with a wiggle of her eyebrows.

“You know what I mean, Bernie. Completely and totally change your life in order to pursue your dream.”

She threw out her arms. “Absolutely completely and totally. Lily, this is the moment I’ve been waiting for my entire life. The point at which everything I’ve been learning, everything I’ve been doing, converges into one great promise.”

“Your entire thirty-two years of existence has come into focus at this moment?”

She beamed at me. “Exactly.”

I didn’t say I’d been joking. This wasn’t a joking matter. Not to Bernie, anyway.

And neither was the matter of what beverage to select for afternoon tea.

Bernie glanced over my shoulder, and her face lit up. She gave a squeal of delight, leapt to her feet, and held her arms out wide. I twisted in my seat to see my grandmother coming into the tearoom. I was pleased that she’d brought her leopard-print cane with her today. She insists she doesn’t need help walking, but I worry about her on the long driveway between her house and the tearoom and on the rough flagstone path in the garden.

The two women hugged each other. My grandmother’s a great deal tougher than she looks, but I’m always afraid Bernie will crush her one day. They’re about as opposite as two women can be. Bernie, whom I called the Warrior Princess when we were kids, is six feet tall, lean, and smooth muscled, with an always out-of-control mane of curly red hair, a complexion dotted with freckles, and green eyes. Rows of silver hoops run up both of her ears; her long thin fingers are covered with silver rings; and colorful tattoos grace her upper back and shoulders. My grandmother, on the other hand, is barely five feet tall and as thin as the cane she held in her knurly hand. Her short gray hair stands up like a halo of spikes around her head, and intelligence and wicked humor shine from the depths of her wide blue eyes. Despite the network of fine lines and deep folds on her face, her porcelain complexion is one women decades younger might envy. This afternoon she wore a long, loose dress in every shade of purple imaginable, with earrings made of purple feathers, and a long double strand of purple beads. Her eyes were outlined by black liner; her mascara thick; and her mouth, a slash of bright red lipstick. My grandmother is a woman who likes color in her life.

“Good afternoon, Rose.” Cheryl put the pot of Darjeeling on the table, along with cups, saucers, matching plates, a milk jug, and a sugar bowl. I’d asked Cheryl to use my personal dishes—the Royal Doulton Winthrop set of white china with a deep red border with delicate gold leaves running through it, and gold trim on the base of the cups and decorating the handles. The china had been given to me by my maternal grandparents, Rose and her husband Eric, on my sixteenth birthday, and it was now kept on a shelf at the back of the kitchen, to be used on very special occasions. Such as welcoming my best friend to Cape Cod.

“Will you be joining us for tea, Rose?” Cheryl asked.

My grandmother took a chair. “I will.” She sniffed the air. “Not Darjeeling, though. I’m in the mood for Lapsang souchong. No food for me, thank you. I had lunch earlier.” Rose had lived in the United States for almost sixty years, but her accent still carried memories of her native Yorkshire.

“Oh!” Bernie said, “I should have had that. Lapsang souchong is an even more exotic name than Darjeeling. What’s the difference?”

“Darjeeling’s from India and Lapsang souchong’s from China, for one thing. Lapsang is smokier and has a slight sweetness, whereas Darjeeling is slightly muscatel, like the wine.” I gestured toward the pot. “Darjeeling first flush was once called the Champagne of teas. Shall I pour?”

“Let me, let me.” Bernie clapped her hands together, and I smiled at the memories of our childhood. “Enthusiastic” could have been Bernadette Murphy’s middle name.

“So,” my grandmother said as Bernie carefully allowed a stream of dark, fragrant liquid to fill my cup. “Tell me what you’re doing here, Bernadette. Lily says you’ve quit your job and have some mad idea of making it as a writer. ”

“I didn’t say it was a mad idea,” I protested.

“You didn’t have to,” Bernie said. “Everyone else does.”

“Including me,” Rose said. “A job’s a valuable thing to have. One doesn’t give up a good job for no reason.”

“I have a reason,” Bernie said. “I’m writing a book, and Cape Cod is the perfect place to do it.”

Rose’s expression indicated exactly what she thought of that. As though her expression wasn’t enough, she added, “Rubbish.”

Bernie threw me a glance. I shrugged. “I’d forgotten,” my friend said, “just how blunt you can be, Rose.”

“Never paid to beat about the bush when I was a girl. My parents were plainspoken, and they taught me to be so, too.”

“I doubt you were plainspoken, as you put it,” Bernie said, “to your employers in that stately home in Yorkshire.”

“I can hold my tongue,” Rose said. “When I need to. Thank you, Cheryl. And you brought my favorite cup, as well.”

Why a souvenir of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer’s wedding was my grandmother’s favorite cup, I never did understand.

Along with the fresh pot of tea, Cheryl placed a three-tiered tray on the table. Freshly made scones on the middle tray, a selection of thin sandwiches on the bottom, and delicate pastries on the top.

“Wow!” Bernie said. “This looks so fabulous. You made all this, Lily?”

“I did, but I have to confess that at this time of day, all you get is leftovers.”

“I’ll eat your leftovers anytime. Everything looks so delicious. Where should I start?” Without waiting for an answer, she selected a plump raisin-dotted scone. She cut it in half, slathered it with butter and strawberry jam, and topped it off with a huge dollop of clotted cream.

I took a salmon sandwich for myself and watched Bernie take the first bite of her scone. Her eyes rolled back in her head, and she moaned happily.

Rose caught my eye and gave me a wink. Even after all these years and all the sandwiches and pastries I’ve made, I still get a flush of pride seeing the fruit of my labors so beautifully presented and enjoyed.

It was after four thirty, and Tea by the Sea, my tearoom, would be closing soon. The last few customers of the day were finishing their tea, scraping the bottom of the jam jar, licking clotted cream or sandwich crumbs off their fingers. Most of my work was finished for the day, except for the clearing up, and so I’d invited Bernie to come in for tea. She’d arrived last night from New York City to spend the summer on Cape Cod

“You’re renting the Crawford place, I hear,” Rose said.

“Yup,” Bernie replied. “I was lucky to get it for a reasonable rent.”

“That might be because it’s falling down.” Rose sipped her tea. “Not to mention falling off the cliff. I trust you’re aware they couldn’t get any vacation rentals this year.”

“Uh, yes, they told me that.” I’ve known Bernie since we were in kindergarten. I can always tell when she’s lying: she’d known no such thing. “It’s going to be the perfect place to write. In the big sunroom that looks out over the sea.”

“If you have good binoculars,” Rose said, “you might catch a glimpse of the ocean on an exceptionally clear day.”

“Well, uh, yes, but it’s very quiet.”

“Because no one risks their undercarriage on that laneway,” Rose said.

Bernie threw me a panicked look.

Rose leaned across the table and put her hand on Bernie’s. “Don’t listen to me, love. I know what rents are like on the Cape in season. You were lucky to get any place at all at an affordable rate and wise not to spend all your savings on something nicer than you need. I’m delighted that you found someplace so close to us.” My tea room’s situated on the Outer Cape, the peninsula part of Cape Cod curling north and west. We’re close to the vacation town of North Augusta, south of North Truro, facing west, looking over Cape Cod Bay, rather than the open Atlantic Ocean.

Bernie grinned at her. “Thanks, Rose. You know I value your opinion. That house will be perfect for me. I’m going to be able to get so much work done there.”

“Which you’ll never find a publisher for,” Rose said. “And that’s if you ever finish the thing.”

Bernie’s smile faded, and she blinked.

“That’s rather harsh, isn’t it, Rose?” I said. “Bernie has talent, tons of it. She just needs the time to get her book finished.”

Bernie nodded enthusiastically as she spread a thick layer of jam on the second half of her scone.

“I believe in speaking the truth,” my grandmother said. “At all times. Such as telling you, Lily, that that cucumber sandwich has too much color.”

“I added a touch of curry powder to give it some punch.”

“A cucumber sandwich does not need punch. A properly made and sliced cucumber sandwich speaks of tradition. There’s a chip in Bernie’s cup.”

“There is not.”

“Opposite the handle.”

Bernie held up the offending cup, and we both peered at it.

“So there is,” I said. At eighty-five, my grandmother has better eyesight than I do. “Don’t change the subject. Bernie wants to take a shot at her dream. Reach for the brass ring. I say go for it.”

“I say rubbish.”

I glanced at Bernie. She looked rather stunned. People often do after my grandmother says what’s on her mind. Not more than ten minutes ago, I’d been thinking Bernie was making a big mistake, quitting her job as a forensic accountant at a big Manhattan corporate law firm, cashing in her savings, and coming to the Outer Cape to work on her book. Now, in the face of Rose’s opposition, I was firmly on Bernie’s side.

What’s the point of having dreams if you can’t strive for them? I glanced around the tearoom. My tearoom. Owning my own place had always been my dream. That the dream came with a well-meaning, loving, caring but opinionated and always interfering grandmother might not have been part of the plan. But sometimes we have to settle for what we can get.

Rose finished her tea and reached for her cane. She wobbled slightly as she got to her feet. Bernie leapt to assist her. “So nice to see you, love,” Rose said. “Never mind what I said earlier. I’m delighted you’re here, and I hope to see you regularly over the summer.”

“You will,” Bernie said.

“Come for dinner one night soon. Tomorrow would be good. Nothing fancy. Lily, you’ll come also. Seven o’clock. A bottle of that nice New Zealand sauvignon blanc you brought last time would be lovely. Oh, that nasty man was back just now, with his binoculars and his clipboard. He waved at me as I walked over here. I did not return his wave. I’m not happy at him poking around. See you in the morning, love.” She walked away, her cane tapping at the wooden floor.

Bernie dropped into her chair. “I’d forgotten what a force of nature your grandmother is.”

“I can never forget. No matter how much I might want to.”

Bernie studied the sandwich selection and helped herself to a cucumber one, made in the traditional way, with thin slices of the vegetable served on white bread spread with a layer of cream cheese and cut into fingers. I’d added a sprinkling of curry powder to the cream cheese for a modern touch.

“I don’t like the taste of curry on this,” Bernie said as she chewed. “It’s overpowering.”

“It is not. You’ve let Rose influence your thinking,” said I, who’d only seconds ago changed my mind about Bernie’s venture, not wanting to agree with Rose.

The chimes over the door rang as the last customers, a table of six women, left. Cheryl swooped down on their table with her tray and began clearing it off. I was pleased to see that scarcely a crumb remained.

My other waitress, Cheryl’s daughter Marybeth, came in from the garden, also laden with a tray. She’d earlier taken a double tea stand outside, and only a single tiny strawberry tart was left. I smiled to see it: the guests had been too polite to take the last one.

“That’s the end of them,” Marybeth said. “And I’m beat. It’s been a good day.”

For most of the day, every table in the tearoom as well as those outside in the garden had been full. It was late spring in Cape Cod, the weather was perfect, and the tourists were out in force.

“What did Rose mean, a man with binoculars and a clipboard has been nosing around?” Bernie said. “That doesn’t sound good.”

“It’s none of our business, but I’m afraid Rose is going to make it so. He isn’t interested in our property. The house next door’s for sale. It has been for some time.”

“Have they been having trouble selling? It’s a fabulous location,” Bernie said. “Almost as good as Rose’s house.”

“It’s a marvelous old house, yes, and in a great setting, but it needs an enormous amount of work. Or so I’ve been told. I’ve never been inside. It’s been owned by a wealthy local family for generations. They used to use it as a summer home, but the family lost interest years ago, and it’s been falling slowly into disrepair for decades. They need to bring the price down—a lot—if they’re going to attract a buyer who just wants a nice house to live in. In the meantime . . .”

The chimes over the door tinkled.

“I’m sorry,” Cheryl called, “but we’re about to close.”

“We won’t be long,” a deep voice boomed. “I hope you can rustle up a cup of coffee and a couple cookies for two hardworking men.”

I turned to check out the new arrivals. They were both middle aged, but the similarities ended there. One was tall and round bellied, with chubby cheeks, a nose crisscrossed by a network of red lines, and thin strands of hair stretched into a comb-over. He wore jeans that looked as though they’d been recently ironed, a blue button-down shirt with the top button undone, and steel-toed boots without a trace of dried mud on them. He had binoculars around his neck and an iPad tucked under one arm. This must be the man Rose had seen. She’d mistaken the iPad for a clipboard. The other man was short and thin, with close-cropped hair and black-rimmed eyeglasses. His pants were part of a business suit, and the sleeves of his white shirt were rolled up.

“You’re in luck,” Cheryl said. “I haven’t emptied the coffeepot yet.” Tea by the Sea is strictly a tearoom, but we have to make accommodation for guests who (shudder!) don’t care for tea. “How about two strawberry tarts to go with it? That’s about all we have left.”

“Sounds good,” said the larger man.

“Maybe the house needs—” Bernie started to speak, but I cut her off with a touch to my lips and a shake of my head. She opened her eyes wide but said no more.

“Nice place you got here,” the smaller man said.

“Thank you.” Cheryl poured the coffee into takeaway cups. “Cream? Sugar?”

“Two of each,” the bigger man said.

“Nothing for me, thanks,” the other one said. “You been here long?”

“If you mean me, my entire life,” Cheryl said. “If you mean Tea by the Sea, this is our first summer.”

“I bet the tourist ladies love it.”

“They do.”

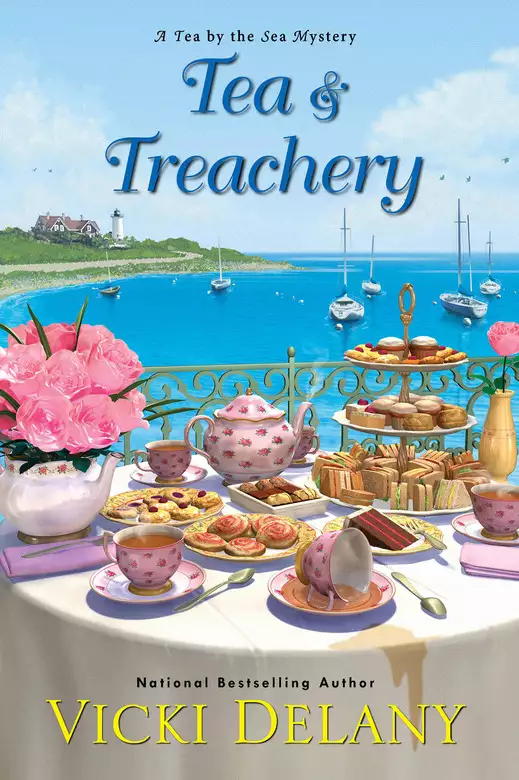

Tea by the Sea specializes in traditional afternoon tea. In keeping with the theme of the menu, the restaurant’s decorated as though it were a drawing room in a castle in Scotland or a stately country home in England. Paintings of British pastoral scenes and horses at the hunt are hung on pale peach wallpaper with clusters of pink and green flowers. The wide-planked wooden floors are polished to a high shine; the chairs upholstered in peach and sage green; the tables laid with starched and ironed white cloths and either a single rose in a crystal vase or a lush flower arrangement, depending on what’s currently available in the garden. Several small alcoves, similarly decorated, are tucked into corners, providing space for small parties or intimate gatherings. In the main room, a large antique sideboard, bought at a good price and carefully restored with a lot of elbow grease on my part and advice on Rose’s, exhibits some of the china tea sets we use. The opposite wall has a real fireplace, at this time of year filled with flowers. A small room next to the kitchen displays items for sale—teapots and matching cups and saucers; tea accessories such as infusers and strainers, timers, and tea cozies; several varieties of prettily packaged tea bath salts I make myself from fragrant tea leaves; and locally made jams and preserves. The waitresses wear knee-length black dresses under starched white aprons and small white caps. As I stay strictly in the back, doing the cooking, I usually come to work in jeans and a T-shirt.

“Do you do a good business here?” the larger man asked.

Cheryl threw me a glance. “We do, Mr. Ford.”

His back was to me, so I couldn’t see him smile, but I heard it in his voice. “You know me. Then you know I care about the success of small independent businesses, such as this one.”

I sipped my tea and listened. Bernie filled her plate with more sandwiches and tarts.

“If you’re a local,” he continued, “you must realize this place won’t get a lot of business over the winter.”

“No,” Cheryl admitted.

“You’re out here in the middle of nowhere. Nice location, close to the sea, fabulous views, but nothing much else around. Am I right?”

Another flick of Cheryl’s eyes toward me. I still said nothing.

“Same with the B & B next door. What capacity do they have? Five guest rooms? Maybe six?”

“I’m not sure.” Cheryl put the strawberry tarts in a paper bag and handed it to him.

The shorter man said, “Can’t be much more than that. Not enough, really, to keep the place going year-round.”

He pulled out his wallet, but Mr. Ford said, “Put your money away, Roy. This one’s on me. I can buy you a coffee, I think, without anyone accusing you of taking a bribe.” He laughed heartily. The smaller man, Roy, didn’t return the laugh.

“We do okay,” Cheryl said.

“This is your restaurant’s first season,” Mr. Ford said. “Soon the novelty will wear off, winter will set in, and customers won’t be able to sit out in that nice garden.” He handed her a twenty-dollar bill. “You need to keep the customers coming in, isn’t that right, Roy? Keep the change. Nice talking to you. I’m sure we’ll be seeing a lot more of each other.”

They walked away. As they passed my table, Mr. Ford turned his head and looked directly at me.

He hadn’t been talking to Cheryl, I knew. But to me.

“What was all that about?” Bernie asked after the men had left, Marybeth started stacking the chairs onto the tables, and Cheryl got out the vacuum cleaner.

“The bigger man was the one Rose was talking about earlier I think. The house next door isn’t selling as a house. There’s talk that a hotel chain wants it.”

“They want to use it as a hotel?”

“They want to turn it into a hotel, which isn’t the same thing. Not just a hotel, but a hotel and conference center. Maybe even a golf resort.”

“It’s big, but it doesn’t seem that big . . .”

“It’s not, and that’s the point. Right now the property’s zoned residential and small business, same as Rose’s property. There’s some talk of rezoning, so the old house can be gutted and a big new extension added on.”

“You’re talking as though that’s a bad thing,” Bernie said. “Is it?”

I let out a breath. “To Rose, it is. I believe the phrase she used is ‘over my dead body.’ You see, what we have here . . .”

“Nicest piece of private property in this part of the Cape.”

“Precisely. Peace, quiet, serenity. I don’t know how much of that we’ll lose if they go ahead with the development, but I’m thinking a lot. Hotel, golf resort, conference center. All of which need parking and round-the-clock staffing. A full-service restaurant and bar means delivery vehicles up and down the driveway all day. No, Rose isn’t at all happy.”

The vacuum cleaner started with a roar. I held up one hand, asking Cheryl to turn it off. “You know who those men are?” I asked her.

“The one who did all the talking is Jack Ford. He’s a big-time developer. Does work all over the Outer Cape.”

“Does he, now?”

“Yup. And he’s as nasty and crooked as they come.”

“Strong words.”

Marybeth joined us. “People have strong opinions about him. The old-timers, like Mom and me and the rest of our family, hate him. The newcomers, the big property owners, and the developers love him.”

Cheryl nodded. “He thinks he’s charming. They say some women fall for that.”

“Who was the man with him?”

“Roy Gleeson. He’s a town councillor,” Cheryl said.

“Thus the comment about not offering a bribe. What do you suppose he was doing here?” I asked. “Not interested in supporting my small business, I assume.”

When Tea by the Sea had its official grand opening in the spring, plenty of officials from North Augusta and other towns in the Outer Cape came, but Roy Gleeson hadn’t. The mayor of North Augusta had made a speech. Or so I’d been told. I’d been in the kitchen, frantically trying to save a batch of brownies burning in the unfamiliar oven.

“If Jack Ford wants the property to be rezoned,” Cheryl said, “someone on council has to propose it. Roy’s checking things out. I bet Ford’s courting them all. He’ll be trying to find someone he can pay under the table for it.”

“Roy’ll get a kickback if the property’s rezoned,” Marybeth said, “and the development project goes ahead.”

“Do you know that for sure?” I asked.

“No, but... ,” Marybeth said.

“Everyone knows,” Cheryl said.

“Meaning no one knows,” I said. “Not for sure.”

Cheryl shrugged, and the vacuum started with a roar. Marybeth returned to stacking chairs.

“I’ll take that as a subtle hint you’re closing.” Bernie tossed the last bite of her pistachio macaron into her mouth.

“Yup. See you tomorrow night. You know Rose’s dinner invitation is a command appearance, right?”

“I wouldn’t dare miss it.” She got to her feet, and I walked with her to . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved