Follow the Tiger

Extinct animals just don’t get up and walk out of museum display cases — especially if they’re stuffed.

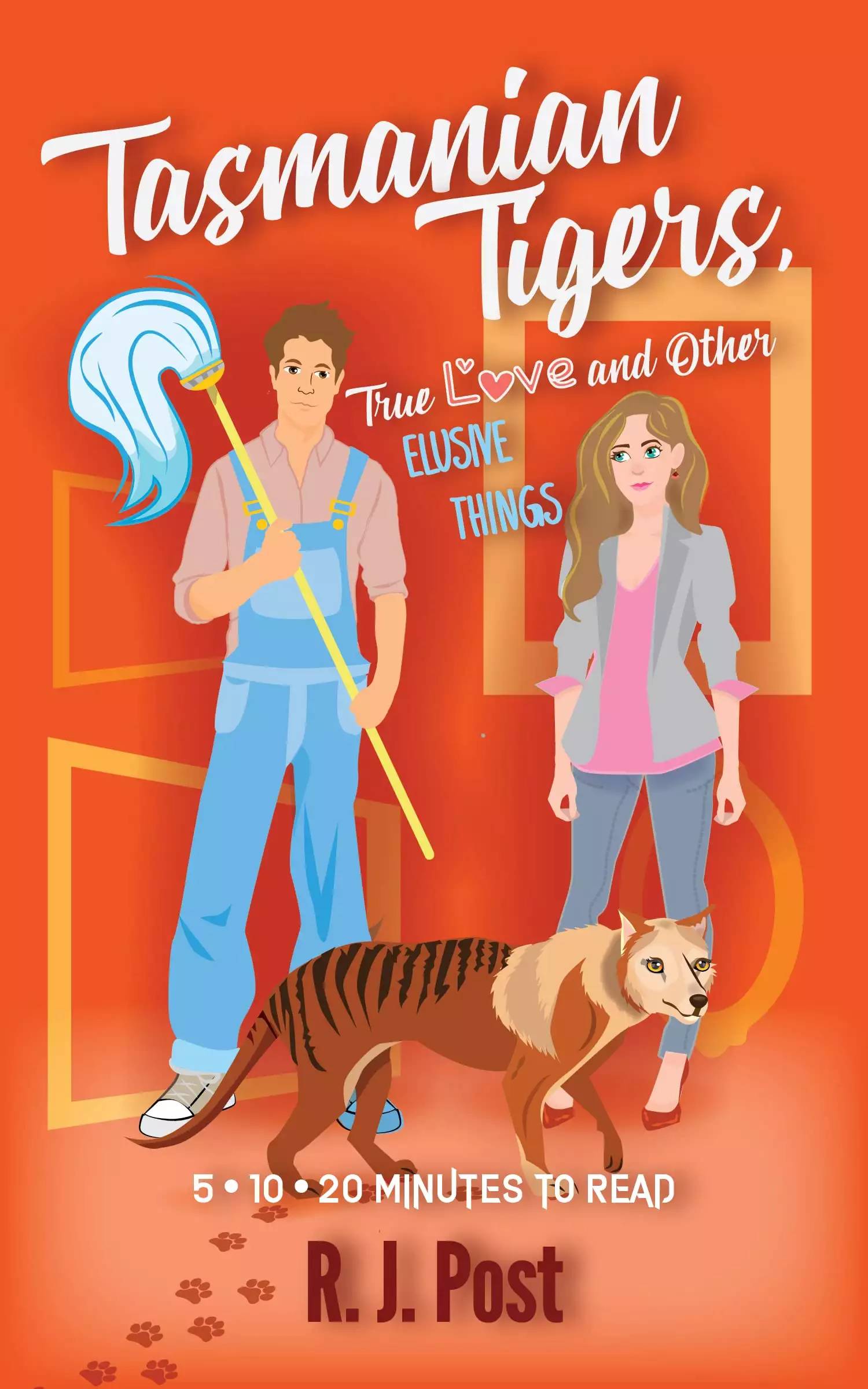

Archie, the 6-foot-2-inch beanpole of a work-study student in penny loafers, dungarees and a blue janitorial smock, knew that much for certain. Yet there he was, scratching his mop top with the handle of a feather duster, while the thylacine stared at him from the other side of the glass — and laughed!

“Do thylacines laugh?” he wondered aloud. “Or is that just hyenas?”

Archie recalled from his zoology class that the so-called Tasmanian tiger made a coughing sound, like a bull terrier in need of a Smith Bros. lozenge, but since they’d been extinct since 1936 — thylacines, not cough drops — no one knew for sure.

The tiger worked its narrow snout open and closed, turned its striped rump and vanished down the hallway of the Megillah Museum of Natural History, playfully wagging its 2-foot-long tail.

Archie had been assigned to clean the Australian exhibit — full of taxidermied kangaroos, koalas and the like — and had no more than unlocked the tiny panel in the side of the display case and squeezed through when he spotted the errant animal.

“Well, carry me out with the tongs!” the boy bellowed, wedged back through the door like a giraffe through a juicer and gave chase.

Paw prints on the freshly mopped floor led Archie to the lobby, where a docent named Sabrina, whom he recognized from his Cyber Social Justice class, was working the reception desk.

“Did a thylacine pass this way?” Archie asked breathlessly as he slid to a stop on the damp tile floor.

“You mean Scooby?” she asked, twisting her sun-streaked hair into a bun and securing it with a pencil. “I think he ran into the gift shop.”

Archie found the gift shop cashier, Mrs. Baumgartner, a middle-aged woman with bouffant hair and cat-eye glasses, taking refuge behind a display case as the tiger repeatedly tossed a multicolored Koosh ball into the air with its mouth and caught it again.

“I-I didn’t know it was Bring Your Pet to Work Day,” she said timidly. “You really should keep your dog on a leash!”

“He’s not my dog. He’s a carnivorous marsupial, and he’s been extinct for 85 years.”

“Oh?” Mrs. Baumgartner said. “You mean he’s got a pouch?”

Just then, the thylacine tossed the ball at Archie and bounded out an open window.

Archie raced back to the lobby, out the museum’s front door and past the 9-foot-tall statue of Gigantopithecus, which the students called Mr. Pit. In the Kane College custom, 5-foot-2-inch Chasity was attempting to leap into the air and high-five the primate’s paw for luck before her Medieval Lit midterm.

“C’mon, Chas! Lay some skin on Mr. Pibb!” her 6-foot roommate, Chelsey, was saying. “It’s easy.”

“There you go again, being taller than me on purpose,” Chasity snorted. “And it’s Mr. Pit!”

After a few attempts, the taller girl genuflected in front of the statue while her smaller friend stood on her knee to perform the ritual.

Out on the quad, some frat boys were playing Frisbee when the thylacine leapt into the air, caught the disc on the fly and landed with a splash in Friendship Fountain.

“Hold that tiger!” Archie shouted, but the beast had already sprung from the water, shaken itself off like a drenched Dogo Argentino and sprinted into the cafeteria.

Cries of “Hey!” and “Gonzo!” rang in his ears as Archie bumped into one table and careened off another, chasing the Tasmanian tiger through the dining hall. Crashing through the swinging doors to the kitchen, he saw the beast wolfing down a pan of boneless chicken wings.

The tiger raised one brow in a sort of guilty expression and gave a short whimper before scurrying out the back door.

Ducking into McCarthy Hall, Archie’s repeated query of, “Have you seen a thylacine?” met with answers like, “Myla who?” and “Hyoscine? I think they keep that in the chem lab.”

Archie caught a glimpse of the critter’s striped hindquarters turning into a classroom and arrived just in time to see it vault onto a laboratory table and jostle the gap-toothed Dr. Lucier. The startled prof inadvertently spilled one beaker into another, setting off a plume of purple smoke that sent students into a panic.

Archie followed the thylacine back into the hallway where he ran smack dab into a stout security guard.

“Listen, bub,” the guard said, pointing the rubbery antenna of his walkie-talkie at Archie’s chest, “you better get that beast of yours under control!”

The thylacine stepped between the guard and Archie and let out a low growl. The officer stumbled backward and ran out of the building.

“Hmm,” Archie thought to himself. “Maybe a Tasmanian tiger can change its stripes.”

He slipped off his web belt and looped it around the tiger’s neck like a collar and leash.

As he led the animal back across campus, he responded to calls of “Nice dog, what’s his name?” “What do you call that thing?” and “What’s his handle?” with “Tas,” “Spot” and “Land Rover.”

Sabrina looked up from her computer — where a headline read, “Is the Mysterious Tasmanian Tiger Really Extinct?” — as Archie returned to the museum, Tas obediently trotting alongside.

As they headed down the hall with the taxidermied exhibits, the beast quietly slipped his makeshift collar and disappeared.

Archie tried to explain to Dr. Morrill, director of the museum, that the thylacine had somehow come to life and gone on a romp across campus.

“Nonsense, my boy! It’s been here all along,” Morrill said, gesturing to a display case, “in the Tasmanian exhibit. You’ll clean this one next.”

Sure enough, Archie saw a stuffed and threadbare thylacine standing stiffly in the display case. When he saw the fierce little Tasmanian devil, standing beside it with teeth bared, he took off his smock and handed it to Dr. Morrill.

“I quit,” Archie said.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved