- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

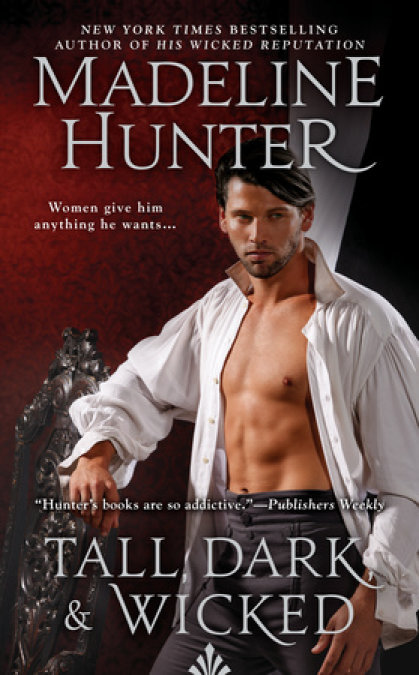

A wickedly wonderful new romance from the New York Times bestselling author of His Wicked Reputation

Most women will give him anything he wants. She is not most women …

As a well-known barrister and the son of a duke, Ives confines his passionate impulses to discreet affairs with worldly mistresses. A twist of fate, however, has him looking for a new lover right when a fascinating woman shows up in his chambers, asking him to help save her father from the gallows. Unfortunately, he has already been asked to serve as the prosecutor in the case, but that only ensures close encounters with the rarity named Padua Belvoir. And every encounter increases his desire to tutor her in pleasure’s wicked ways.

Having always been too tall, too willful, and too smart to appeal to men, Padua Belvoir is shocked when Ives shows interest in her. Knowing his penchant for helping the wrongly accused, she had initially thought he might be her father’s best hope for salvation. Instead, he is her worst adversary—not least because every time he looks at her, she is tempted to give him anything he wants.

Release date: October 6, 2015

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Tall, Dark, and Wicked

Madeline Hunter

Praise for the novels of Madeline Hunter

Jove titles by Madeline Hunter

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Special Excerpt from The Accidental Duchess

CHAPTER 1

Loyal

Good-humored

Intelligent

Uninhibited

Passionate

Accommodating

Lord Ywain Hemingford—Ives, to his family and closest friends—read the list of the qualities he required in a mistress. He had jotted them down, in no particular order, during an idle moment the day before. Only the first one deserved its ranking without question. In fact, it should be underlined. There were other qualities that attracted him, too, but these six, he had learned through experience, were paramount.

He tucked the paper behind some pages, to be returned later to its current duty as a marker in his book. He settled into his favorite chair, propped his legs on a footstool with his feet aimed toward the low fire, and again turned his attention to a novel he had been meaning to read for four months now.

Vickers, his manservant, set a glass and two decanters, one of port and the other of water, on a table next to the chair, then stepped back out of view.

“If your brother the duke should come by this evening, sir, should—”

“Deny him entrance. Bar the door. I am not home to him. If God had any mercy he would have inspired Lance to remain at Merrywood Manor, not allowed him to venture back up to town where he will be a nuisance to all whom he encounters. I am done with being his playmate, or his nursemaid.” At least for a while, he added to himself. After a recent, renewed week of barking, the hounds had again retreated, but they had not given up the hunt.

Ives did not mind being his brother’s keeper. He resented very much playing the role for a brother who treated his advice like it came from an old aunt. One would think that a man under suspicion of murder would be more circumspect in his speech and actions, and want to create favorable impressions, not stick out his tongue at society whenever he could.

“Very good, sir.”

Padding steps. A door closing. Peace. Ives closed his eyes and savored for a moment that rarity in his life—freedom to do whatever he damned well pleased, whenever he chose, with nary a claim on his time or attention.

Several developments allowed this respite besides the dwindling interest in Lance by magistrates out for blood. No cases awaited his eloquence in court for at least a fortnight. By coincidence his mistress had a week ago been most disloyal, giving him the excuse he had sought for some time to part with her.

That left him free of her too. Of attending on her. Of purchasing gifts. Of feeding her vanity. Of joining in little parties that she liked to hold that bored him more than he ever let her know.

It did, of course, also leave him free of a sexual companion. That was not a situation that he by nature welcomed, but he did not mind too much. Contemplating with whom to end his abstinence would give his forays out on the town an enlivening distraction.

He anticipated a glorious stretch of pointless activity. Several long rides in the country beckoned, following whim more than roads or maps. A stack of books like this one waited, too long unread. He could indulge in regular practice with sword and fists, to improve his prowess at fighting with both. And he looked forward to at least one good long debauch of drunkenness with old friends too long neglected.

“Sir.”

Vickers’s voice, right at his shoulder, surprised him. He had not heard Vickers return.

“Sir, there is a visitor.”

“Throw him out, I told you.”

“It is not your brother. It is a woman. She says she has come on business. She says you were recommended to her.”

Exhaling a sigh, Ives held out his palm.

“She gave me no card, sir. I would have sent her on her way, but she would not indicate just who had recommended you, and the last time such an unnamed recommendation came your way it was from—”

“Yes, quite right.” Damnation. If someone, or even Someone, thought to interfere with the next fortnight by having him running around England on some mission or investigation, Someone was very much mistaken. Still, he should at least meet this woman and hear her out, so he could construct a good reason why he could not help her.

He stood, and looked down at himself. He wore a long banyan over his shirt and trousers. The notion of dressing again raised the devil in him. Hell, it was long past time to call at a lawyer’s office, even if Someone recommended him. He would be too informal for a stranger, or for business, but he was hardly in a nightshirt. This woman would just have to forgive him his dishabille. With luck she would realize she had interfered with his evening, which she rudely had, and make quick work of whatever she wanted.

He walked to the office. She was probably a petitioner for some reform cause, or the relative of a friend looking for his advice on which solicitor to hire. Her mission this evening no doubt could have been completed more humanely by writing a letter.

He opened the door to his office, and immediately knew that his visitor had not been recommended by anyone significant, let alone Someone really important. Her plain gray dress marked her as a servant. He could not see one bit of adornment on either it or the dull green spencer buttoned high on her chest. The simplest bonnet he had seen in months covered her black hair and framed her face.

Eyes lowered, lost in her thoughts, she had not heard him. He considered stepping out just as silently, and telling Vickers to send her away. He placed one foot back to do so.

Just then she lifted a handkerchief to her eyes—glittering eyes, he could not help but notice, with thick, black lashes that contrasted starkly with her pale skin. Radiant skin, as it happened, giving her face a notable presence, if he did say so, even if she was not a beautiful woman. Handsome, however, even if somewhat sharp featured.

She dabbed at tears. Her reserved expression crumbled under emotion.

He hated seeing women cry. Hated it. His easy sympathy had caused him nothing but trouble in the past too. Still . . .

Hell.

He waited until she composed herself, then walked forward.

* * *

Padua sniffed, and not only to hold back the tears that the day tried to force on her. She also checked for the tenth time to discover if her garments smelled.

Newgate Prison reeked. The stench that London gave off seemed to concentrate in the old city, but Newgate smelled like the source of it all. She had never experienced anything like it. It remained in her nose, and she worried that it had permeated her clothing.

She sat rigidly on the chair the servant had pointed out. Her surroundings caused some trepidation. She had perhaps been rash in following the advice to seek out this lawyer. Probably so, considering the person who had given the advice had been a bawd incarcerated in the prison.

Normally, she would not take advice from a prostitute or a criminal. Yet when that woman called her over as she found her way out of the prison, and showed sympathy, she had not been herself. Just talking to someone eased her distress. After hearing her tale of woe, that woman advised she get a lawyer, and even provided the name of one who had aided a relative who was wrongly accused. Suddenly the prostitute appeared as an angel sent by Providence to offer guidance out of the Valley of Despair.

Now she awaited that lawyer’s attendance. Not only a lawyer, but also a lord. She thought it odd that a lord was a lawyer. She would assume the bawd erred on that, except the servant here did not blink when she used the title in requesting an audience.

Now that she was here, she could believe the lord part. Although she sat in his chambers, this was no apartment, nor merely a set of offices. Rather she sat on the entry level of what appeared to be a new house facing Lincoln’s Inn Fields. There had been nothing to indicate that others lived or worked above. This lawyer had a good deal of money if this whole building was his home.

The mahogany furniture and expensive bookbindings said as much. Her feet rested half-submerged in the dense pile of the carpet on the floor. Her rump perched on a chair that must have cost many pounds. Real paintings decorated the walls, not engravings done after famous works of art.

His fees were probably very high. She doubted she could afford them. The bawd had guessed as much. If you’ve not the coin to pay him, he’ll probably take other payment, dear. Them that works our side of the Old Bailey almost all do.

Could she agree to that? She recoiled from the idea. Then again, it would be no worse than the bargains most women struck in their lives. Had her mother not taught her that the loveless marriages to which most women were subjected were merely economic arrangements prettied up by legalities? Experience of the world had shown that view to be harsh, perhaps, but essentially accurate.

She closed her eyes, and immediately was back in the prison, peering into a cell full of men. The stench, the dirt, the ugly sounds all assaulted her senses again. Hopelessness and death reigned in Newgate Prison. No one would leave a loved one inside it, if she had the means to get him out.

Tears pooled in her eyes. She dabbed them away with her handkerchief, and fought for composure. She never cried, but this was not a normal day in so many ways.

“You asked to see me.”

The voice jolted her out of her reverie and drew her attention to the man suddenly standing ten feet in front of her.

Oh, dear. Goodness. He was not what she expected. Not at all.

She had pictured a man of middle years with gray hair and spectacles and a face wizened with experience. He would wear dark coats and a crisp cravat and be accompanied by a clerk or two.

Instead the man assessing her—there was no other word for the way his gaze took her in—could be no older than thirty or so. He possessed classical features and fashionable locks of dark brown hair of an enviable hue. He wore a long banyan that could pass for a greatcoat if not made of midnight brocade instead of wool.

An impressive man. His green eyes captivated one’s attention. Very attractive eyes. Intelligent. Expressive. This lawyer was not merely handsome, but handsome in a way that made fools out of women when they saw him.

She found her wits, lest she appear just such a woman. “Are you Lord Ywain Hemingford?” She had no idea how to pronounce Ywain. Surely not JA-wane, as the bawd had. She tried EE-wane instead. His subtle wince said she got it wrong.

“I am he. It is pronounced eh-WANE, by the way, at least by my family. There are half a dozen options. Almost everyone chooses the wrong one, so I long ago retreated into the name Ives. Think of me by that name, if it is easier.” His perfect mouth offered a half smile. “By either name, you have me at a disadvantage.”

“My apologies. My name is Padua Belvoir.” She took in his informal dress. “I have intruded at the wrong time. I am sorry about that too. I have been so distraught I have not paid proper mind to the hour, and I could not rest until I sought the help I need anyway.”

“You told my man you were recommended to find me. May I ask by whom?”

By a prostitute in Newgate Prison. “I do not think she wants me to tell you her name.”

He strolled across the chamber. “I assume you are here regarding criminal matters.”

“How did you know?”

“Because that is the only reason she would not want her name used, and because I believe you visited the prison today.” Ever so calmly, he opened one of the windows. A crisp breeze poured in.

She felt her face burning.

“Please, do not be embarrassed. The prison is a fetid place,” he said. “I had a coat that had to be burned after I wore it there one summer day.”

“It is not only fetid, but horrible in every way. The conditions are disgraceful. The inmates are wretched.”

He settled his tall body into a chair near hers. He sat in it like a king might sit on a throne. His arms rested along the tops of its sides, and his hands hung in front of its carving. “Have you come to request a donation, perhaps to further a campaign to improve those conditions? I will contribute, but I must warn you that yours is a noble yet futile quest. People tend not to worry overmuch if criminals are not comfortable.”

“I am not here to ask for a charitable donation, although someday I hope to have the time to devote to such good causes.”

“A budding reformer, are you?”

“There is much in our society that could use some reform.”

“As there has been in every society down through time.”

Oh, dear, he was one of those. The kind who saw no point in trying to better the present because such efforts in the past had failed. “I know history, sir. I have received a liberal education. With our superior knowledge, I think we can be more enlightened than our forefathers.”

He resettled himself in that chair, and angled his head. “I would ask which reforms you want to see first, but let me guess instead.” His gaze scanned her from head to toe. “Workers’ rights. Educational reform.” He scanned again. “Universal suffrage, including the vote for women. If you are educated, you would not like being denied a right enjoyed by others who have no more training of their mental faculties than you have.”

“Your conclusion is accurate. However, my reasons are less elevated. I simply believe that since there are many men who now vote who are stupid and ignorant, there can be no logic in denying the right to any others, stupid or ignorant though they might be as well.”

He laughed lightly. An appealing laugh. Quiet. Warming. His eyes showed new depths. “I do not think I have ever heard it said that baldly before. Like a wily math tutor, you have insisted that a different equation be solved, one that puts me at a disadvantage should I want to disagree.”

His insight with that math tutor comment unnerved her. How had they veered onto this topic? “My opinions do not signify, of course. My original point was that not everyone in that prison is a criminal, so the suffering there cannot be excused.”

He offered that half smile again, no more. “Since you do not want money, and you do not want to discuss reforms, perhaps you will explain what you do want.”

“I want your eloquence and skill to help my father, who has been so affected by prison that he is too weak to help himself. He has been wrongly accused of a crime.”

He did not actually sigh at hearing this most predictable topic, but his expression retreated into one of bland patience. “How long has he been there?”

“At least two weeks, but perhaps a month. I only learned about it yesterday. I received a letter, from whom I do not know, telling me. Normally I receive news from him at least once a month. It has been some six weeks since I last received one of his letters, so I had become concerned.”

“Why did you not visit him, and see what was wrong, if the letter did not come?”

“We are somewhat estranged. There was no argument between us. He is just much engaged in his own pursuits. I could not visit, because I do not know where he lives in London.”

“Did you see him when you went to the prison today?”

“I was allowed to visit him. He is in a large cell with many rough fellows. He is unwashed and unshaven and frightened. I fear he will get ill there. So many others are sick.”

“Why was he put there?”

“He would not tell me. He only said to leave and not come back.” Her voice almost caught on the last sentence. The visit had been horrible. If an iron door had not separated her from Papa, she thought he would have physically driven her away.

The green of his eyes darkened while he thought. She did not take the pause as a good sign. Not at all.

“Miss Belvoir, I am sure you were dismayed to find your father in a cell with men unsuitable for polite society. However, if you do not know the crime of which he is accused, how can you know that he is wrongly accused? His refusal to speak of it even with you suggests the opposite.”

“My father is no criminal, sir. He is a scholar. He has taught at universities throughout the Continent and had a position as a teacher at Oxford until he married my mother. He spends all his time on his research and his books. There can be no justifiable reason for him to be imprisoned, unless being an intellectual has now become a crime. A serious miscarriage of justice is about to occur.”

It poured out nonstop, the way her excitement sometimes betrayed her. Lord Ywain—Ives—just sat there, listening, exerting a presence that crowded her despite his sitting six feet away. He did not appear especially interested.

“You are sure of this?” he said.

“I am positive.”

“And yet you do not even know where he lives in London.” His words did not dismiss her outright, but his expression almost did. His eyes had narrowed with skepticism.

She felt her best chance to help her father slipping away.

“I told him that his silence was foolhardy. That is why I am here. I was told that some people have lawyers at their trials now. I was told that you at times speak for those accused.” Slow down. Stop gushing words. “My father is incapable of defending himself, and may even be unwilling to do so. The accusations are insulting, and he is the sort to refuse to engage in the insult by refuting it.”

He had not moved during her impassioned plea. Those hands still rested at the end of the chair’s arms. Attractive, masculine hands, as handsome as his face. His gaze had not left her, and the shifts regarding what he looked at had been subtle but unmistakable. Not only her face had been measured. She did not think she had been as closely examined in her life, let alone by a man such as this one.

She was not an inexperienced young girl. She recognized the purpose of that gaze, and could imagine the thoughts that occupied part of his mind. A small part, she hoped. She trusted at least some of what she had said took root amidst his masculine calculations.

In a different circumstance she might be flattered, but the bawd’s words made the attention dangerous. He did not appear of a predatory nature, and such a man hardly needed to take advantage of an accused man’s female relatives if he wanted to satisfy carnal needs. However, she experienced some alarm and a good deal of confusion. The latter resulted from the undeniable and inappropriate low stirring his attention evoked. She did not want to acknowledge it, but it was there. He was the kind of man who could do that to a woman, no matter how much she fought it.

“You do not know the accusations, so you cannot say they are insulting,” he said.

“Any accusation of a crime would be insulting to a man like my father. If you met him you would understand what I mean. Hadrian Belvoir is the least likely criminal in the world. Truly.”

The smallest frown flexed on his brow. His attention shifted again, to the inside of his head. She ceased to exist for a long moment. He stood abruptly. “Excuse me, please. I will return momentarily.”

Then he was gone, his midnight banyan billowing behind him.

* * *

Hadrian Belvoir.

Ever since his visitor introduced herself, an indefinable something had nudged at Ives. The pokes implied he should know her, yet nothing about her was familiar.

Hadrian Belvoir. That name did more than poke.

He strode up to his private chambers, to a writing desk there where he dealt with personal letters. He rifled through a thick stack of old mail, discarding it piece by piece, frowning while he sought the letter he wanted. Finally he found it.

He flipped it open and held it near the lamp. There that name was, buried amidst a casual communication. You can expect to be asked to be prosecutor for a Hadrian Belvoir, once his case is brought forward. It would please us if you accepted.

He checked the date. This had been written a month ago. No wonder the name had not been in the front of his memory. If Mr. Belvoir resided in Newgate Prison, why had this informal approach not turned into a formal one by now? It was possible his victims had hired their own prosecutor, of course, but if that were likely, these sentences would never have been written.

It would please us if you accepted. Considering who had written this, it went without saying that acceptance was assumed, and would indeed be given.

He would have to inform Miss Belvoir that she must look elsewhere.

He returned to the office and the bright-eyed Miss Belvoir. He had realized, while she talked and talked, that her eyes sparkled even when she did not cry. He had also calculated that if she stood, she would be willowy and long limbed. An idle curiosity had crossed his mind, about what it was like to take a woman who was a good match for his own height. His mind had pictured it, making the necessary adjustments . . .

No sooner had he walked into the chamber than she began speaking. “I think you can see that a great injustice will occur if my father does not receive your help, sir. I beg you to consider accepting his case. I am prepared to pay you whatever fees you require.”

Not likely, from the looks of that dress and spencer. “Miss Belvoir, allow me to explain that no barrister will accept financial remuneration from you for defending in this matter.”

She went still. Her lips parted in surprise. He felt bad that his refusal shocked her, but there was nothing else for it.

She looked up at him, confused. “Are you saying you will do it for free?”

“I am saying that barristers do not get paid by clients; they are engaged by solicitors who take care of such things. Barristers will be insulted if you offer to pay them like they are tradesmen.”

“So I must first find a solicitor and have him ask you. Instead of one lawyer I must hire two.”

“You must find a solicitor to investigate, but I will not be the barrister he engages to argue the case in the courtroom. I cannot be the defending lawyer. When you mentioned your father’s name, I realized I have already been approached to serve on the other side.”

“Other side?”

“Prosecutor.”

She absorbed that. Her full, deep rose lips mouthed the word.

She stood, which brought her close to him. Her crown reached his nose. Yes, she was unusually tall. The scents of Newgate no longer cloaked her. Rather that of lavender wafted subtly, as if by force of will she had conquered the ill effects of the day. Since the glint in her eyes no longer came from tears, he guessed she had, in many ways.

She strolled away, thinking. She moved with notable elegance and a subtle sway. She wore her unusual stature the way a queen might wear a crown.

She turned and faced him. He pictured her in a white diaphanous gown that flowed down her long body, one bound under and around her breasts in imitation of the ancient deities. Only, from the expression she now wore, she might also wear a helmet and shield, like Athena, goddess of both wisdom and war.

“This is awkward,” she said. “However, it is not without value to speak with you.”

“Since I have not even seen the brief, there is nothing to learn from me.”

“It is always useful to meet one’s adversary. Had I not made the error in coming here, I doubt I would have had the chance. I would have arrived at the trial, with you a total stranger.”

“I am not your adversary, Miss Belvoir. You are not the one who will be on trial.”

“We will have opposite goals, so I think the word is accurate.”

“I am sure you will find a worthy lawyer to take up this case for you, as you intended.”

“Having met you, I am not sure I will find one worthy enough. I dare not leave it all in another’s hands now.”

Her gaze penetrated him. He had the sense of his soul being searched by an intelligence as sharp as any he had ever met. Whatever she found, it lightened her expression. Softened her. The unusual beauty that had drawn him into this chamber became much more visible. The sparkles in her eyes implied humorous conclusions.

He knew what she had seen. An acknowledgment of it passed between them in an instant of naked honesty. Hell, yes, she was sharp. He had been nothing but restrained. A bishop could not have hidden his sensual speculations better, but she had still sensed them in him.

She turned those eyes on him fully. Ives recognized the expression of someone about to offer a bribe. A few had come his way in the past. He waited for hers.

Resolve flickered. Boldness flashed. Then, in the next moment, both died.

“I am sorry to have taken your time, and at an unsuitable hour at that. I will leave you to your evening.” She walked toward the door.

“I will find out about the charges,” he said. “That way you will know what he faces, at least. Leave your address with my man, and I will make sure you are informed.”

She turned. “Thank you. That is very kind, coming from someone I must now see as an enemy.”

“I am only an enemy if the truth is, as well.”

That amused her. “Noble words to soothe the helpless woman’s fears, sir? That is generous of you. However, truth depends on the equation, too, doesn’t it? Different variables yield different solutions.”

CHAPTER 2

By the time Padua slipped through the garden behind the house on Frith Street, the last of dusk’s light showed. High-pitched voices leaked from the building’s second storey, where the girls ate their supper. If she moved quickly enough, she could take her own chair in the dining room without attracting much notice. If she were very lucky, Mrs. Ludlow would be none the wiser about Padua’s activities today.

She did not fear Mrs. Ludlow, the gentlewoman who owned this building and school, and in whose hands rested her ability to support herself. Generous to a fault, and as warm as a mother, Mrs. Ludlow suffered from a level of absentmindedness that made her quite benign. Learning one of her teachers had left the property would distress her, however, and Padua did not want to do that.

She checked the garden door, and was relieved to find it still unlocked. She strode through the back sitting room, removing her spencer while she walked. She rolled it up and tucked it behind a chair in the reception hall before mounting the stairs.

Assuming an expression of confidence, she entered the drawing room that now served as the dining room for Mrs. Ludlow’s School for Girls. She made her way to the head table and slid into her chair. She drew no particular attention from the others already into their meals. Only Caroline Peabody’s gaze followed her conspicuously, first with a little frown, then with visible relief. Caroline was one of three girls Padua tutored in higher mathematics. Those lessons were not part of the curriculum, and took place late at night after Mrs. Ludlow retired.

She enjoyed the extra work, because it meant these girls could discover what their minds could achieve. She found contentment in doing for them what her mother had done for her. The pay at this school might be low, but it was a respectable living, one for which she held excellent qualifications. The employment also permitted her to squirrel away some money for the plans she had.

“Miss Belvoir.” Mrs. Ludlow’s address drifted down the table, past the other teachers. “Please join me in my chambers after dinner. I would like a word with you.”

Padua finished her meal while the room emptied. She then made her way to Mrs. Ludlow’s chambers. The door to the sitting room stood open, as it usually did in the evening. Once she entered, however, Mrs

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...