“Star Wars” Program Chief Space Laser Engineer

William F. Otto

In 2011, Perseo Mazzoni from the Italian music group Lunocode contacted me for help with song lyrics about a set of primates launched into space in 1948–51 aboard V-2 and Aerobee rockets. Having grown up in Huntsville, Alabama, where every manned space flight was broadcast over the school’s public address system, I thought I knew the space program, but this was the first I had known of early Air Force and Army flights.

People of my generation are familiar with the Navy feeling pressure to launch a small satellite on the mostly untested Vanguard-derived three-stage missile. We remember because we witnessed the failure on live television in 1957.

The following year, President Eisenhower established NASA to coordinate civilian space exploration and be the public face of the space race. At the time, the U.S. was very concerned with the space environment and its effect on ICBMs. A number of nuclear tests in space were carried out by the Defense Nuclear Agency with assistance from the Navy in Operations Argus and Hardtack II which explored the effects a nuclear blast would have on military hardware, including satellites.

In that same time frame, the Air Force funded the Atlas missile, the Army developed the Redstone, and the Navy the Polaris missile. NASA may have brought civilian space exploration under one roof, but the branches of the service were each going their own ways in the ICBM arena.

It wasn’t just ballistic missiles, but satellites, antiballistic missiles, navigation, communication, and weather. And then the CIA got involved with reconnaissance, and the Advanced Research Project Agency with potential space weapons like lasers and particle beams.

The successor to ARPA, DARPA (the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) was researching the space-based laser when I came into the workforce and I got involved in 1979. Reagan was elected president and soon established the Strategic Defense Initiative. The high-tech world of a “missile shield” exploded into an intense effort that was transferred from DARPA and the Air Force to a new SDIO (the Strategic Defense Initiative Organization, the “Star Wars Office” to the press).

A lot of things were happening. The Air Force centralized their space activities within the Air Force Space Command, but people were mentioning that maybe the services shouldn’t be duplicating efforts and that space activities should be brought under one Space Agency. Others felt that the independent efforts had a higher probability of success despite the duplication.

In the 1990s, GOP leaders spearheaded by Newt Gingrich, Dick Cheney, and Donald Rumsfeld sought an effective missile defense. There was renewed interest in various interceptors like EKV (the Exoatmospheric Kill Vehicle), THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defense), and the Aegis missile. At the time, however, all of these mostly failed to hit their targets.

Congress directed the Air Force to pursue the space-based laser (which would have scuttled the Outer Space Treaty against weapons in space), but the Air Force didn’t believe the technology was ready. Gingrich and Trent Lott responded with a clear threat: If the Air Force had other priorities, then the time had come to set up the U.S. Space Force and shift the budget from the existing branches. I thought this was pretty bold, and it started to look like I would be writing some proposal material after all.

Boeing made me technical lead for their bid to be part of the program. We went through a competitive phase, but after a lot of good work, the Air Force (acting for BMDO, the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization) directed that Lockheed Martin, TRW, and Boeing team up to do the work. I ended up as the systems engineering, integration, and testing lead for the program, or in short, the “chief engineer.”

At a conference in

Oxnard, California, on large space optics at the time, I was shocked by a presenter from the NRO (National Reconnaissance Office). The existence of the NRO had been a highly guarded secret, but he openly announced that not only did they exist, they had worked out an agreement with NASA and the Air Force to share technology. Since I’d worked for all three, I had seen three independent developments of much of the same technologies, a colossal waste of effort.

Times were changing. The idea of a unified Space Force came up again and again, but when it finally happened under the Trump administration, I found a lot of people confused about what the Space Force would do. Was it a bunch of space rangers flying in space, shooting at aliens or their Russian and Chinese counterparts?

That was not entirely out of the question. In 1965, the Air Force had secretly selected astronauts for its planned Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL). You might recognize the names Richard H. Truly, Robert L. Crippen, Robert F. Overmyer, and Henry W. Hartsfield from NASA’s Space Shuttle era. Another, James A. Abrahamson, I knew later when he was the first head of SDIO.

By now the reader will have noted a pattern: despite the Outer Space Treaty which prohibits the development of space-resident weapons, there is a long history of delivering weapons to space, through space, or from space. As soon as innovations allow, they are applied to new weapons—by inventors all over the world. And so, new weapons will continue to be added to the growing U.S. military presence in space, helping prevent attack, support national interests, and ultimately benefit us all. Remember, even the Global Positioning System was originally designed to guide missiles and bombers to pinpoint surgical strikes.

Of course, once valuable hardware is up there, we have to protect and defend it. Imagine if Russia or the United States suddenly lost their early warning satellites. Each would feel vulnerable to surprise nuclear attack, and that insecurity would make hostilities more likely. A large role for the Space Force is in defending the defense assets in space for monitoring and intelligence gathering. But it goes beyond military interests. Much of modern life is space based. Automated teller machines, credit card verification at point of sale, airplane navigation, tour guide navigation, entertainment, news . . . almost everything you can think of depends on space assets. Farmers program their harvesting machines to follow a GPS track. If satellites were attacked by some rogue power, much of modern commerce would grind to a halt. People would starve. We must defend our space assets with every bit as much diligence as our airspace.

And there’s no doubt that some of the concepts and technologies to do that were inspired by science fiction. One of the more talked about space resident weapon concepts is Jerry Pournelle’s “Rods of God” in which orbiting tungsten rods are de-orbited over an enemy and

allowed to strike a target with kinetic energy roughly equivalent to a tactical nuclear warhead. Although there are significant technical challenges with this concept, it shows how science fiction and technology spur each other forward. I know I was inspired by countless science fiction movies in the fifties and sixties along with shows like Star Trek, The Outer Limits, The Twilight Zone, and The Time Tunnel, and so were many others producing defense concepts and ideas over the course of the past fifty years. We still call SDI “Star Wars” after all!

But science fiction doesn’t only generate ideas, it also gets us to think about the world in new ways. The 1985 Canadian movie Def-Con 4 comes to mind, and illustrates why we will probably always have a military presence in space. This anthology is in the same vein, with a mix of fact and fiction to inspire both reflection and innovation. There are articles about the Space Force, its origins, trappings, and mission, and stories that inspire and that present new ideas and concepts that can find their way one day into experimental or even everyday operations—for space defense and everyday life.

It was Arthur C. Clarke who, in a 1945 letter to the editor of Wireless, suggested that geostationary satellites would be ideal for global communications. That attracted the military, but it ultimately revolutionized everything from logistics to weather forecasting, to delivery of entertainment on transoceanic flights. How many ideas in the volume you’re holding will one day be equally transformative?

Let’s find out.

—William F. Otto

Albuquerque

***

After consulting for DARPA on chemical lasers, Bill Otto was the technical lead for Boeing’s Space-Based Laser Integrated Flight Experiment, and later lead systems engineer for the Air Force Space-Based Laser joint venture that formed the backbone of President Reagan’s “Star Wars” Strategic Defense Initiative. A Boeing Technical Fellow and member of the Missile Defense National Team, he enjoys science fiction and can often be found listening to Feynman’s Lectures on Physics while doing projects around the house.

Preface

The idea for this anthology sprang from my first introduction to what is now the United States Space Force back in 2017, when as guest of FenCon XIV in Dallas, I was to moderate a panel called “Join the Space Corps: Improvise, Adapt, Overpower.” Sounds pretty badass, right? And the other panelists were heavy hitters, including a veteran NASA astronaut and a Lockheed Martin engineer working on Air Force weather satellites. I would be asking the questions and I’d never heard of this “Space Corps,” so I needed an education—fast.

The panel description told me that in June of that year, the House Armed Services Strategic Forces Subcommittee had voted to create a Space Corps as a subset of the U.S. Air Force, similar to the way the Marine Corps is set up. Google opined that the new Trump administration opposed the measure, that Defense Secretary Mattis had taken the unusual step of writing a letter in support of a Republican amendment to kill it, arguing the idea was premature and in need of more study.

In fact, though, while perhaps new to most voters and to staffers within the new administration, this idea had already been studied to death. I’d not given the defense of satellites much thought since my school days, when it had occurred to me that bold as President Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative might seem, in practice it would have been a trillion-dollar sitting duck to anyone with a cheap sounding rocket and a bag full of gravel. Little did I know, smart people were way ahead of me.

Satellites have become critical not only to the military, but the entire economy, providing an ever-growing range of services for which substitutes are inferior, uneconomical, or downright impossible. The need for an independent military organization to protect them had been suggested long before Ronald Reagan, and had been proposed in earnest by bipartisan commissions and panels under both Presidents Bush (George W.) and Obama. The reasons were several and included the growing importance of space to defense and the economy, the scattering of existing space defense responsibilities across various military organizations, and the Air Force’s perceived bias toward airplanes at the expense of procurement for and attention to space.

Thus enlightened, I led my panelists in a lively debate and we went on with our lives. Then a few months later, I attended the 2018 International Space Development Conference in Los Angeles to receive a writing award. This conference was an amazing display of space-related entrepreneurship and energy: programs to help college students launch science payloads into space, Cold War cannons promoted for blasting propellants into orbit, serious work on space-elevator design, shiny scrap from the manufacture of rockets turned into skateboards and coasters, inspiring stuff. Everywhere were hopeful idealists and promoters eager to ride the impending wave of commercial space exploitation to be ushered in by plummeting launch costs.

I got my picture taken with Dr. Frank Drake (of the Drake equation fame), and Freeman Dyson (famous for his work on atomic pulse propulsion). I met actor Harry Hamlin and lent a cell phone charger to Rod Roddenberry, son of Star Trek creator Gene. Then on the last day, after the last session before my cab came to take me to the airport, I met Lieutenant Colonel Peter Garretson, then director of the Space Horizons Task Force at the Air Force Command and Staff College.

Peter was not one to mince words. Sooner rather than later, the Space Corps was going to happen, he said. The time had come, and while it wouldn’t exactly be a space navy anytime soon, wherever people and their interests go, the military and the law must eventually follow. He said that around the college, he liked to say they were building the “real Starfleet Academy,” and he told me he’d thought of producing a science fiction anthology to help get the word out.

That piqued my interest, and Peter and I batted the idea around over the next few months. I let the matter drop after he moved on from the Air Force, and in December of 2019, the independent space-defense service branch that had been recommended under Reagan, Bush, and Obama finally got the nod, though the man in the Oval Office by then wanted to call it a “force” instead of a

“corps.” The name made no difference. Political theater aside, to those of us in the know, this was expected and largely a non-story.

Then in early 2020, when the nascent service branch started making announcements, my social-media feed lit up with confusion and outrage. It wasn’t surprising that late night talk show hosts made light of the new military branch—that’s literally their job. Nor was it surprising that Netflix rolled out a workplace comedy inspired by such a high-profile event. Or really, that taxpayers unaware that the DOD’s Space Command had already existed in one form or another for twenty-five years would balk at the news of a new space-related defense force. If you didn’t know any better, you could be forgiven for imagining space stations teaming with Velcro-receptive combat boots.

The 2020 Netflix television series Space Force was created by Greg Daniels and Steve Carell, who previously worked together on the hit TV show The Office. Both have said they were inspired by announcement of the creation of the United States Space Force in 2018, but only because they were looking for ideas for a new workplace comedy at the time. In interviews, they’ve said the show was not intended to make any political statement or to belittle the real U.S. Space Force and that actual members of the U.S. Space Force were consulted in order to make the show more authentic and respectful of the real branch.

All of this was understandable, and after all, the announcement came through an administration if not a uniquely polarizing force in American politics, certainly a lightning rod for existing polarization to align and compound around. Among Donald Trump’s detractors, no decision was beneath derision, not even one with bipartisan support grown over six administrations that he actually had little to do with. The Internet memes were as cynical as they were profligate. Several featured images of Trump’s face pasted onto Pixar’s Buzz Lightyear character over the caption “To insanity and beyond.”

The jokes were understandable, but they reflected a certain naïveté about the need for space defense in particular and the military in general. Would the Pentagon really rip off Star Trek? Would it really create a whole service branch just to waste money sending Marines into orbit? Was all this really just saber rattling by an unpopular president, boondoggle of boondoggles, the dreaded “militarization of space” where no such thing was warranted? Or had smart people looked into the matter and learned things the jokesters and meme-makers didn’t know? Clearly, there was a perception problem.

No rational person wants war, but most people understand that as someone once said,

a nation too civilized to fight will soon be conquered by its less civilized neighbors. The more I investigated, the more reasons I found for taking space defense seriously.

In 2019, India conducted a missile test that resulted in the creation of space debris, posing a risk to other spacecraft in orbit. Russia and China have both successfully tested antisatellite missiles. In 2018, a Russian satellite approached a U.S. government satellite close enough to conduct a close inspection or attack, forcing evasive maneuvering. The same year, China launched a satellite that analysts believed was equipped with a robotic arm that could be used to manipulate and disable other satellites.

Why does it matter? For a start, it’s worth pointing out that GPS satellites are what make modern precision bombing possible. You might hate war, but when someone else decides to start one, GPS is the biggest single aid in reducing collateral damage. And satellites aren’t just up there guiding explosives and pizzas to their destinations; they play a critical role in everything from weather forecasting and disaster response to agriculture and environmental monitoring. Taken together, satellites contribute nearly $200 billion a year to the U.S. economy, which is more than the individual GDPs of half the states.

That’s a lot riding on 1,300 high-tech machines, many costing twice their weight in gold even before launch and operating costs, all as lightweight as possible and with delicate optics, sensors, antennas, and solar arrays utterly exposed in the vacuum of space. It would be foolish to pretend they don’t need to be protected. So, as the son of an Air Force Cold Warrior myself, I thought the nine thousand or so real, live human beings serving their country within the new Space Force and all their families and dependents deserved a little bit better than dismissive Internet memes. And since I had edited a few small anthology projects and was looking for something more challenging . . . and having achieved some success as an author and, as the great Edward Abbey once put it, an “explainer,” I decided to do as Gandhi advised us, and “be the change you wish to see in the world.”

Thus, after many false starts and dead ends, it was coincidentally on the last day of the 2022 International Space Development Conference at which I was receiving another award, after my last session before the taxi whisked me away to the airport, that Baen Books editor Toni Weisskopf pulled me aside to say she’d publish the anthology if I’d just go ahead and do it already.

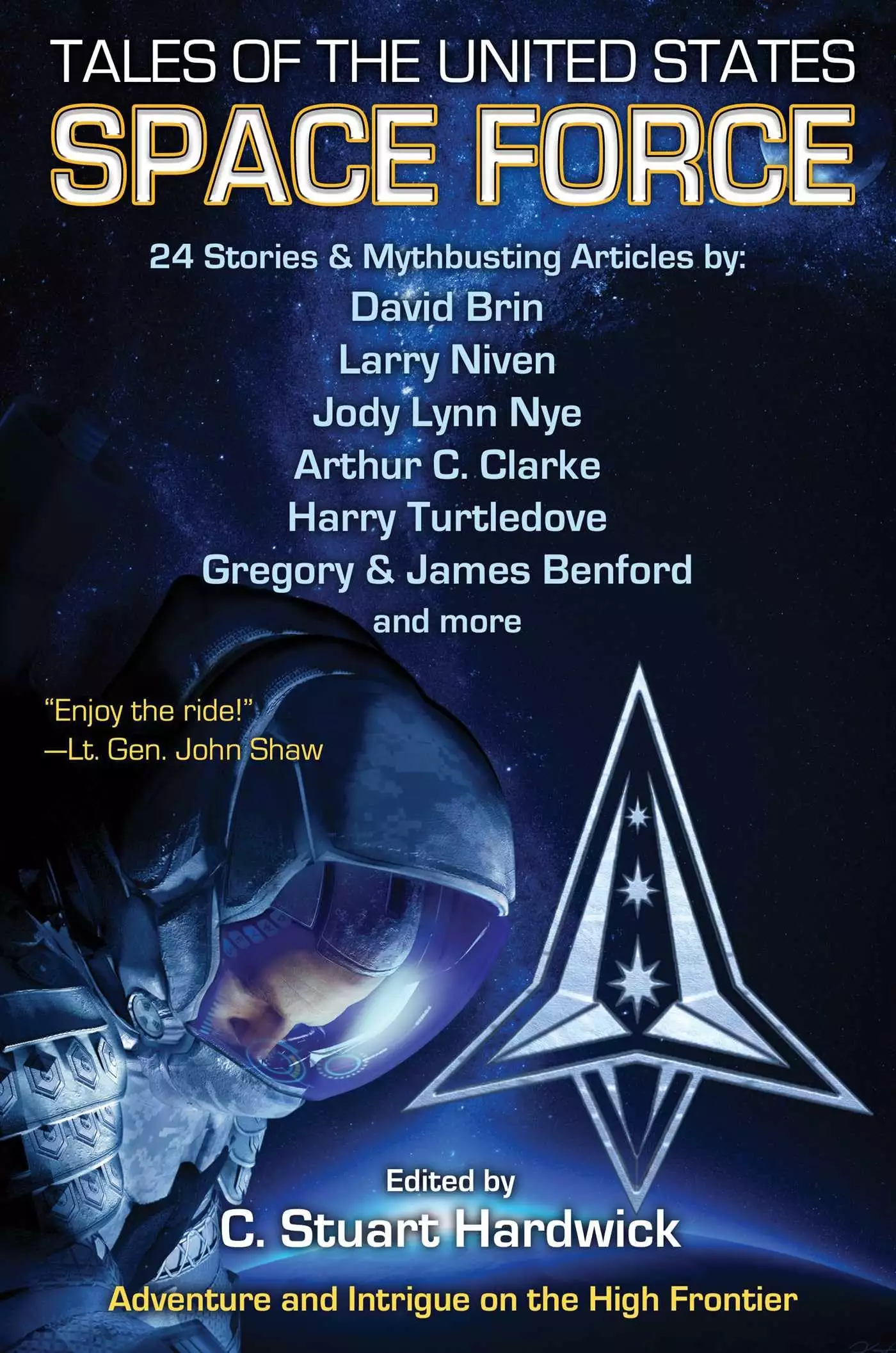

Thus, ladies and gentlebeings, I give you this anthology in the hope it will enlighten, entertain, and inspire. Enlighten you as to the true origins and mission of the Space Force and its accouterments and paraphernalia. Entertain you with thrilling adventures in space and here on the ground, some of which give a taste of what real-world space defense is all about. Inspire you, as science fiction always has, to see something important beyond your own life, to walk

in another’s footsteps, and perhaps, just perhaps, to one day take a chance and thus find wonders beyond present imagining, maybe even beyond the stars.

And so, inspired by one notable schoolmaster, I enjoin you in paraphrase of another: Let us step into the great vast night, and pursue together that flighty temptress, adventure.

—C. Stuart Hardwick

Houston

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved