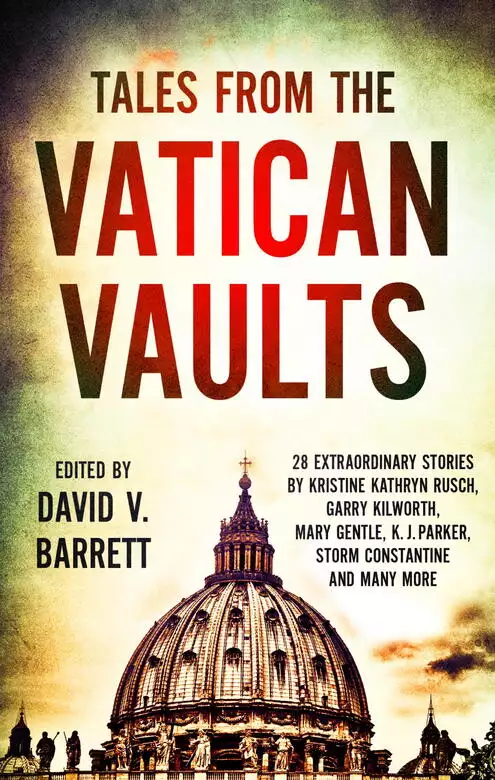

Tales from the Vatican Vaults

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A captivating collection of original science fiction and fantasy stories based on the same alternate world premise: a collection of documents that have been suppressed by the Vatican and hidden away for years, in some cases centuries, are revealed when the vaults are thrown open by a reforming pope. In this alternate reality, Pope John Paul (I) does not die a month after his accession in 1978; instead he lives on for over 30 years to become the most reforming pope of all time. In addition to relaxing the rules on birth control and priestly celibacy he also opens up the most secret parts of the Vatican Library to scholars . . . In the Vatican's deepest vaults, documents are discovered which shed new light on world history, containing information which, if true, would cause many parts of accepted history to have to be rewritten. These include not just the undercover involvement of the Catholic Church in world affairs, but documented accounts of what really happened in historical conundrums, the real lives of saints and popes, miracles, magic, angels and even alien encounters.

Release date: December 27, 2016

Publisher: Constable & Robinson

Print pages: 576

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Tales from the Vatican Vaults

David V. Barrett

Among his many achievements Pope John Paul was the longest-reigning pope, his thirty-two years and two months passing Pius IX by six months. And he was the oldest pope ever, living till just past his ninety-eighth birthday, easily passing Leo III who lived to ninety-three, and remaining sound in mind and body until the end.

But it is not for these remarkable records that we celebrate John Paul’s papacy. It is the fact that he ushered in an age of liberalism previously unknown in the Catholic Church. We shall recall shortly how he dealt with a number of difficult moral issues, some of which were making the Church of Rome seem out of touch with the modern world.

*

First we must repeat our gratitude to Pope John Paul for opening up the deepest, most secret parts of the Archives of the Vatican Library – known colloquially as the Vatican Vaults – to scholars. In doing so he has made available an incomparable wealth of historical material.

This act was not without risk, as John Paul himself accepted. Even more so than the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Nag Hammadi Library and other caches of ancient documents, who could tell the impact of what might be found in the Vatican Vaults? Certainly there would be skeletons; the Church’s undercover involvement in world affairs throughout the centuries would be laid bare.

We know already that the Church of Rome has at times been involved in covering up things it did not wish to be known, and at times has blatantly rewritten history. The best known example of the latter must be the Donation of Constantine, an eighth-century forgery which asserted that the early fourth-century Roman Emperor Flavius Valerius Constantine gave the papacy spiritual sovereignty over all other churches, temporal sovereignty over large parts of Italy and landed estates throughout the Middle East for income. The Church continued to use this to assert its temporal rights long after it had been proven to be a forgery.

As we explore the thousands of documents in the Vatican Vaults, much of the history of the last millennium or more will have to be re-examined; the separation of fact from fiction is one of the hardest tasks facing the scholars. It might take generations of historians and theologians to sift through what is buried in the Vaults, separating out suppressed first-hand accounts from clever obfuscations.

Over the last twenty years we have only skimmed the surface. The research team has deliberately been kept small and manageable, rather than opening up the Vaults to an academic free-for-all. There have been papers, monographs and, for a few research assistants fortunate in their choice of supervisors, there have been doctoral theses. I was one of the first of these, and so owe my career as an historian to Pope John Paul. Two decades later I find myself chairman of the committee which would select and publish a popular edition of some of the material found in the Vaults.

Like John Paul, we are taking a risk in publishing this book. The accounts span over a thousand years. They cover a wide variety of subjects. Some challenge the foundations of the Christian faith. Others challenge our view of the world, with their revelations of the supernatural or the paranormal, of the spiritual or the alien. All are startlingly different views of the history we thought we knew.

Can we take all of these as verified history? Of course not. History is not an open book, a clear narrative from Then till Now. There are few certainties, only greater or lesser probabilities. Many of the accounts in this book may be completely factual; others may be fictions and fables which the Church, for whatever reason, wanted to hide. We hope that the notes before and after each one will guide the reader; we have, in many cases, erred on the side of caution.

As with scholars in all areas of academe, historians disagree with each other. Few of these accounts were a unanimous choice; most are the result of many hours of argument, with passions raised both for and against. This is part of the joy of scholarship, and I would like to thank my fellow committee members for not (quite) coming to blows, and for their enthusiasm and humour in both formal meetings and informal conversations.

*

This book is in itself a tribute to Pope John Paul. We must mention here just a few of his reforms during his many years as Pope.

Probably his first revolutionary action was to throw the moneylenders out of the temple. Within weeks of coming to office he was looking into the corrupt state of the Institute of Religious Works, commonly known as the Vatican Bank, and within months he had required several high-ranking officials, including an archbishop, to resign. The Commission of Enquiry into Financial Mismanagement was the first of several commissions he set up with the explicit mandate to ‘find out where the Church fails, and show us how to make things right’.

The Commission of Enquiry into Abuse in the Church initially looked into the now-infamous Magdalene Laundry asylums in Ireland and Australia, and quickly closed the few remaining ones. It then turned its attention to the sexual, physical and mental abuse of children by priests, monks and nuns, Pope John Paul refusing to continue the Church’s unspoken policy of quietly covering up both the problem and the scale of it. From the beginning this commission worked closely with both police and social services, ensuring that all who had committed abuse against children would answer for their crimes.

John Paul was not afraid to challenge long-held practices of the Church, including that of priestly celibacy, which was always a discipline rather than a doctrine. The first stage, early in his pontificate, was to allow already married men to enter the priesthood; later the rules were relaxed further to allow priests, under certain circumstances, to marry and remain as priests.

This was part of the Pope’s rapprochement with the Anglican communion, his warm relationship with a succession of Archbishops of Canterbury being a constant feature of his long papacy.

Five years after he became Pope, John Paul brought about a most remarkable, yet at its heart remarkably simple, act of reconciliation between the two Churches. In 1896 Pope Leo XIII declared that all Anglican consecrations of bishops were ‘absolutely null and utterly void’ because there were gaps in their continuity of Apostolic Succession, the laying-on of hands from bishop to bishop over the centuries. The Anglican Church, naturally, disagreed.

For most people this dispute was as abstruse as how many angels could dance on the head of a pin. But for bishops and priests it was a major focus of division between the Churches.

Pope John Paul’s solution, symbolically on Whit Sunday (Pentecost) 1983, was to bring together all the bishops of both Churches in cathedrals around the world in joint services of re-commitment of their faith and re-consecration of their ministry, with all laying hands on each other. Some criticised it as an audacious sleight of hand, and hardline Ulster Protestants called it worse than that, but the way that it was done, with smiles and hugs and slappings on the back as well as the formal laying-on of hands, somehow pulled off the minor miracle that from that day on, all Catholic and Anglican bishops recognised each other as equally valid.

Undoubtedly the reform with the most widespread effect was John Paul’s relaxation in practice of the Church’s teachings on contraception. Condoms were permitted for the prevention of disease, and the Pill if it was being used to regulate a woman’s cycle or for other medical reasons; contraception was an unwished-for but unavoidable side effect. Again it was a sleight of hand, but one welcomed by millions of ordinary Catholics worldwide, who could continue to do what they had already been doing, but now without sinning.

*

It could all have been so different. If Pope John Paul’s personal secretary had not chanced to go into the Pope’s private rooms late at night to retrieve a book he had left there, and seen the light still on in the Pope’s bedroom, and found the Pope slumped in bed from a heart attack, and called the Vatican physician and an ambulance – we might have lost this most reforming of all popes just a month after he ascended St Peter’s throne. There would have needed to be a second conclave in 1978, and a new pope would have had to be elected. Who can guess what differences there might have been in the years between then and now? But there we are sliding into the realms of alternative history.

Prof. Francis Atterbury OBE, FRS

Durham, 2015

The story of Pope Joan has been believed and denied for around a thousand years. Numerous essays and books have ‘proved’ both the truth and the falsehood of the tale, and many would say that this account can lend no credence to the myth, for reasons which will rapidly become obvious; yet the mass of supporting detail requires that the possibility of its truth not be discounted out of hand.

This account in tenth-century Italian was in a folder entitled ‘Johanna Anglicus, a woman’, found among the personal papers of Pope Sergius III (904–911 CE) along with several letters, notes and diary entries which make reference to it. From internal evidence and from its prose style, particularly the shifts of tense to heighten the immediacy of emotion, it appears to be a transcription of Pope Joan’s own dramatised oral tale, told by her to her family in or just outside Rome some time in the first few years of the tenth century.

It was a time of tribulation, and more. Everything, which had been going so well, so wonderfully, fell apart, flew apart – and most galling of all, I can place little of the blame on anyone other than myself.

Maybe Antonio, a little – but only a little. It was my carelessness, not his, that nearly lost us everything.

Oh, I had such power – had priests and princes bowing to me – and lost it through my lusts.

I wished, often then and sometimes even now, that I had never left Germany, that I had never left my family; that grey, rainy country so different from this sweating, plague-infested Rome; that arguing, fighting, loving, supporting family so different from the arguing, fighting, hating, back-stabbing men of God here.

But I was very young, in our years, still just nearer to thirty than to forty. It was my time to travel, to find new experiences on my own, but not for myself only: we always bring back what we have learnt and tell it to each other, that we may all share, may all learn.

Remember this, my children, when you begin to travel.

We were an English family, though we lived in Mainz. One of my fathers, for reasons I didn’t understand as a child, was a missionary to the Germans. I was brought up in a house of scholarship. From my childhood I knew myself to be a scholar rather than a merchant or a farmer; and I knew also that I could not be tied, as several of my mothers were, to the family home. My birth-mother had left early for her final Wandering, having brought three healthy litters of children into this world and then into adulthood; she’d had enough of fetching and carrying, of cooking and cleaning, of being a wife among many and a mother of many.

‘Don’t let yourself get trapped, as I have been,’ she told me. ‘I wanted to study, but I ended my travels too soon and joined this family. A wonderful family, don’t get me wrong, but I have spent too much time thinking of us, not enough of me.’ She went on, my mother, a good deal more than that, but it all meant much the same: she’d been familied too soon, before learning to be herself.

I must not do the same. She told me, and I knew it for myself.

I would be a scholar, and there was only one place for that: the Church. No matter that, like all of us, I had no belief in God; I have none now and had none even in that highest position – but then, neither had many of my predecessors, nor many of my successors, I am sure. Here in Rome, at the very centre of the Church, there is less faith than anywhere else in Christendom – and almost no Godliness. It shocked me when I first arrived here, even though I was well aware of how dishonest humans are.

I did not wish to join a nunnery; there is too much devotion there, and – with some exceptions – too little scholarship. I changed to man’s form and joined the Benedictine abbey at Fulda, near to our home in Mainz.

Why? Because there, I was among some of the finest minds in northern Europe. I could learn from them, argue with them, study their work first hand, read more books than were collected almost anywhere else, except Rome – and here they are collected but not read, not studied. There is no scholarship here; only fighting for position.

I listened and studied and learnt, and argued and taught and wrote. And made the beginnings of my reputation.

From there I went to Athens to extend my studies to Greek literature – and there, unknowingly, I took my next fateful step.

Each mistake is greater than the one before, each built on all that has gone before. This one seemed so right, so wonderful, so (if I’d believed in God and an afterlife) heaven-sent.

Danger, danger, danger. Why did I not see? Because I was blinded by that which lights one’s life but throws all that one does not wish to see into the shadows. Love.

Love!

Antonio and I met first in a tavern, where as a brother under the Rule of Saint Benedict no doubt I should not have been; but too many of the brothers knew their scholarship only as a dull, dry thing, unrelated in every way to living. I had to breathe. There in the ancient squares and taverns I found release in conversation with men and women of all sorts and conditions, in rough wine and, from time to time, in women. Some I paid, but most became friends and friendly bedmates.

In a man’s body I enjoyed bedplay with women; I would have liked the occasional man, for inside I was still deeply female, but there was too much risk.

In the abbey I could have had a dozen of the brothers; but I would rather have fornicated with a rotting dead pig than touch one of them or have them touch me.

I sensed Antonio across the tavern, just as he sensed me; our eyes touched across the room. I bought a carafe of wine and wandered as if casually over to the quiet corner he had moved to.

‘Antonio of Verona, known as Brother Andrew of Tours.’

‘Gerberta, of an English line, known as John of Mainz.’

We touched hands shyly, eagerly. He knew I was female.

I’d come across many others of our people over the last few years: the odd young traveller like myself, a few older ones on their twilight Wandering, and families here and there. We’d met, we’d talked, we’d spent evenings together sometimes – but we’d never got close. It almost seemed that I could make friends – shallow friends, anyway – more easily among humans than my own people.

But Antonio . . .

From that first meeting there was a power between us, a communication deeper than any I had known before. We were lovers from that first touch between our eyes; and only hours later we became lovers in bed also.

We made love first as two human men, because we couldn’t wait to change our forms. And then later, the following morning, we made love again as ourselves, in our true forms.

It was the first time in five years that I had enjoyed the sexual sensations of my female body.

*

Oh, how easily are we betrayed!

*

And when I moved from Athens to Rome, Antonio came with me; neither of us even considered that he might not.

*

Oh, there are times when I wish I believed in God, for then I could cry out in the depths of my despair, ‘Why, why, oh Lord?’

*

I taught at the Trivium, in the Greek church attached to the Church of Santa Maria in Cosmedin. I became well liked and well respected for my learning, in that city of influence and ignorance. In time, Leo IV gave me a cardinal’s hat –

– and when his successor, Benedict III, a holy man whom in other circumstances I might have loved, died, I was acclaimed Bishop of Rome. I said no, of course; I said I was not worthy; I hid myself in St Peter’s. But the crowd would not hear my protests, and said it was God’s will.

*

Oh God, I wish I could believe in you. I could beg for your help, or at the least for your solace; I could take comfort in the promise that you would protect me; I could try to persuade myself that all this is part of some great divine plan, that you know what you are doing, that good will come of it in the end; or I could rail against you for what you have done to me.

But I can only rail against myself, and know that my help cometh only from myself, in whom I despair.

*

Antonio and I were careless in our loving, just as young lovers should be. It never crossed our minds that I might become pregnant; after all, we had no group marriage, there were only the two of us, and this gave us – this should have given us – the sexual freedom that our young people enjoy. Sex for fun, sex for play, sex for excitement, sex for friendship, as well as sex for love. Sex with a glorious variety of partners, experimenting with and enjoying the gifts of our bodies and minds and spirits and emotions, the gifts to give as well as those to receive. Sex without the responsibility of children – that’s what group marriages are for.

I should not have become pregnant, not outside a group marriage; but I did. We were stunned, horrified, Antonio as much as I . . . then over the weeks and months we grew more used to the idea, began to look forward to it. I had never been a mother, and was at the age when I should begin to think about settling down in a marriage group. Maybe my body, fooled by my being with Antonio for three or four years, thought I was in a group marriage . . . a group of two.

We made plans. The baby was due in June of the year 858, a hot and filthy month when my absence from Rome would be regarded as sensible. We would go to a villa up in the hills, where there would at least be trees to shade us from the blazing sun, and where we would be away from the filth and stench and disease of summer Rome – and from the intrigue, the watching eyes and wagging tongues.

I had brought Antonio with me from Venice as my priest-attendant, and he still attended me as my cardinal deacon and secretary. It was expected that where I went he would go also.

*

Oh, Antonio! So beautiful, my only love, and you are gone. So beautiful, and so close to me, you turned down propositions almost daily from the fat priests and cardinals and dukes and administrators who jostle for position and power and wealth, who bribe and steal and seduce and kill to raise their social standing by one small degree, to move from one sphere of influence into a vying one, to gain another rich jewel or bag of gold, and all in the name of the God of love.

He wanted none of them; he wanted only me.

And I lose him, I lose him, and our child.

*

You know the place, some of you: between the Colosseum and the Church of St Clement. The day was hot, sticky, sweaty, as so much of that summer had been. The air itself seemed diseased. The Rogation Day procession between the Lateran and St Peter’s wound slowly through the streets, priests and cardinals and choirboys before and behind me, a hundred pious nuns walking together in their midst.

My bearers stumbled from time to time, exhausted by the heat. I had tried to cancel the procession, the ceremony, but that body of administrators who actually run this hellish place would not allow it. It was tradition, it was custom, it was law. I, as Pope, had no say in the matter.

My time was near, but not too near: three or four weeks. This was my last compulsory appearance before I could flee this filthy place with Antonio; tomorrow we would go into retreat for the rest of the heat of summer, and I would have our child in peace.

*

The pain hits me and my waters break forth, together. I’m soaked from my loins down, and going into spasm; my entire body heaves and thrusts. I scream with the agony. One of my bearers, startled, chooses this moment to stumble; the litter tips and falls, and I with it.

My body reacts to the emergency without my conscious thought; I feel my vagina, closed with a fold of skin beneath my penis, open up and widen, widen suddenly and agonisingly as the baby within pushes itself into the world.

Priests, cardinals, attendants of all sorts, rush to my aid, knowing only that their Pope has fallen and is hurt.

I lie half on the ground, half still in the soaked finery of my litter, my legs wide apart as the thing inside me tears itself from me. And cries.

That tiny infant sound stills the hubbub around me. Choirboys, monks, nuns, priests, cardinals in their sweat-stained robes, all stop, and stand, and turn, and stare. And then they come for me, for me and for my barely born child, with their fear and their hatred, their boots and their fists, kicking and clawing and tearing and stamping . . .

*

Three days, now, three days to repair my ripped and ravaged body, but three lifetimes would not be enough to repair my torn heart.

*

Somehow I crawled away and hid, in rotting piles of rubbish in the shell of a half-broken building only a few minutes away from my scene of degradation and discovery and despair. Hid, until I could stop the bleeding from my own wound, my womb which had betrayed me, and from the cuts and tears and rough grazes and bone-deep bruises from the mob’s attack.

And while I healed, I changed my appearance: I made myself a hand’s width shorter, I changed my hair from its distinctive copper – a legacy from an Irish forebear – to black, and I made my face rounder and more anonymous. I remained a man; my attackers, the tribunals of the Church, the entire priesthood, half of Rome for all I knew (though some might secretly admire my presumed audacity) – all would be looking for a woman.

Now I was safe, at least from recognition, though my weak state would make me more prone to the illnesses of the city.

I sought out a small family group I knew, and told them what had happened. They were amazed, but they took me in; though we may fight and squabble among ourselves, we will always help each other against human threats, and besides, with my new appearance, there is no danger to them.

*

Three days, my children, three days and I have heard nothing. My child is gone, Antonio is gone: my baby no doubt torn apart or trampled underfoot, as they tried to do to me; Antonio – I do not know. I cannot believe he has deserted me. He was in the procession, near to me; if he tried to come to my help they may have taken him, beaten him, killed him.

There is little value placed on human life in this festering city, when it is not one’s own. His body may be in the Tiber, with so many others; I have asked the Fantonis, the family who have taken me in, to listen for reports.

I could so easily have been in the Tiber myself.

There have been popes from our people before, three of them, but none lasted longer than my two years, five months and four days. They fared no better than most other popes. Maybe one day it will come that popes are not ripe for assassination, by knife or strangulation or by subtle poison; but even a pope’s life is cheap when ambition rules.

All of Rome is buzzing with stories of how the Pope gave birth by St Clement’s, and the greater amazement of the Pope being a woman. Such a thing has never been heard! I do not know if it has happened before; it is possible, though there is nothing in our history, and it would have been still more difficult for a human woman.

*

It was another week before Antonio and I found each other. He too had changed his appearance – he was taller, thinner – but I recognised him at once, and he me. Perhaps it is by our scent, that even if subconsciously we can know each other; this is, after all, the main way that we know each other from humans. Perhaps we recognised each other’s individual scent across the piazza.

But I prefer to think it was our spirits calling to each other in their love.

You can imagine the joy with which we fell into each other’s arms, even those of you too young to know the love between two adults. Each of us had pictured the other dead, trampled and pulled apart, or else captured and tortured and longing for death. (I still hear the screams from the dungeons of the Basilica in my sleep at night; Antonio will tell you. Those tortured in the name of the God of love know the depths of agony and degradation, if ultimately they know nothing else.)

Each of us had searched that plague-strewn city; each had listened everywhere for rumour, while hoping desperately we would hear none. Each of us had so narrowly escaped that we could not imagine the other having also such fortune.

People were beginning to stare, and in a city so leprous with suspicion that was dangerous. We remembered suddenly that we were both male in appearance. We drew back, looked into each other’s eyes, laughed gaily (it was hard, but it was so easy!), and clapped each other on the back like old friends who had not seen each other for a long time.

‘I did not even know you were in Rome,’ Antonio boomed.

‘I didn’t know you were either,’ I replied. ‘My wife, her sister is dying, and so I brought her. And you?’

Antonio looked sly. He glanced around as if to see who might be listening, then lowered his voice – but still kept it loud enough that those nearby, straining, might hear.

‘I am here . . . on business, shall we say. A merchant friend of mine, he told me of a deal I could make . . . He let his voice fade away as we walked away, across the piazza, through an alley and into the anonymity of a crowded street. Our eavesdroppers, I knew, would smile and shrug; such deals were commonplace, and the reason many came to the city. Some were lucrative, but most came to nothing.

We walked through the crowds, yearning to touch each other, to hug, to hold, even just to say something to show our love for each other, our joy at finding each other.

Antonio led me into a small inn, and to a quiet corner. And it was only when we were seated, with a jug of rough red wine between us, that I thought – suddenly, sickeningly, with overwhelming guilt – of our child.

Antonio saw the change on my face, and reached over, laying his hand on my arm.

‘It’s all right,’ he said, ‘he’s safe.’

I couldn’t speak. My sight went grey, then white, then black. It was some time later when I realised that Antonio was holding a cold, damp cloth to my forehead and neck.

‘It’s all right,’ he said, over and over again. ‘It’s all right.’

I sat back, and the dim interior of the inn slowly came into some kind of focus. Antonio gave me my beaker, his hand steadying mine as I raised it and drained it in one long gulp.

‘Our son is safe,’ he said, and my destroyed world, my distraught spirit, were made whole again.

It was only an hour – it seemed a month – before I held our son for the first time. He had beautifully thick dark hair and deep blue eyes, and his tiny fingers closed on mine. His body was human in shape; Antonio told me he was changing from his natural birth appearance to human almost as soon as he was born. Instinctive mimicry: our deepest survival trait. But at birth he had looked like us, unchanged, and his initial appearance, then the flowing of his infantile features as his body adjusted them to human, had compounded the horror of the Pope giving birth. This was a monster, a demon, devil’s spawn. Small wonder that the priests and cardinals and other dignitaries and their attendants had tried to kill both him and me.

Antonio had had one moment in which to act, when, horrified by the tiny squirming creature before them, these holy men had turned their attention to a horror they could cope with: me. He snatched the baby, tearing the cord with his nails, and tucked him into his robes, then let himself be pushed back as others pushed forward to get at me.

He didn’t know, he told me as I sat with our son cradled to my still human, still male breast, how he was able to leave me. But I maybe had a chance, however small; the tiny mewling creature had none without his immediate help, his full attention, his love and care and devotion. Apart from safety, our baby needed food, literally in the next few minutes. His first act in life had been to change his appearance, which drained him of every scrap of energy he was born with. If he were not given food, and then safe sleep, straight away, our son would die.

Antonio, my beloved one, my darling husband here, saved our son. Like me, he found friends to take him in, and one, who had recently had a litter of three children, had milk enough to feed our baby as well. It was fortunate in many ways that my first birth, as sometimes happens, was of only one child.

The two families lived at opposite ends of this teeming city, but knew each other well; two of the wives in ‘Antonio’s’ family were sisters of two of the husbands in ‘mine’. Together they helped us away from Rome, to a quiet village three days’ ride away, and to a quiet farmhouse in the hills above the village.

There, for the next few months, Antonio and I could live as ourselves when we wished, though for the most part we retained our human appearance.

We both preferred his new, leaner look to his old, so he kept this; I reverted to my old appearance, which I had when I was a girl in Mainz, with a little added maturity we both agree

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...