- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

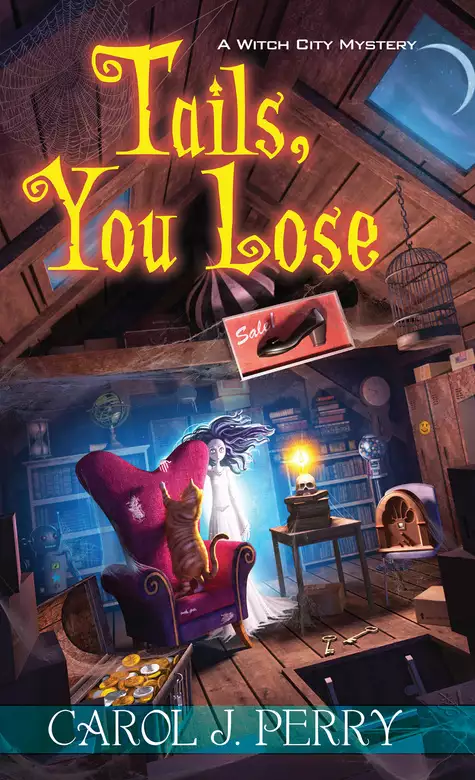

Synopsis

After losing her job as a TV psychic, Lee Barrett has decided to volunteer her talents as an instructor at the Tabitha Trumbull Academy of the Arts-known as "The Tabby"-in her hometown of Salem, Massachusetts. But when the school's handyman turns up dead under seemingly inexplicable circumstances on Christmas night, Lee's clairvoyant capabilities begin bubbling to the surface once again.

The Tabby is housed in the long-vacant Trumbull's Department Store. As Lee and her intrepid students begin work on a documentary charting the store's history, they unravel a century of family secrets, deathbed whispers-and a mysterious labyrinth of tunnels hidden right below the streets of Salem. Even the witches in town are spooked, and when Lee begins seeing visions in the large black patent leather pump in her classroom, she's certain that something evil is afoot. But ghosts in the store's attic are the least of her worries with a killer on the loose . . .

Release date: April 1, 2015

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Tails, You Lose

Carol J. Perry

I’d pulled a big wing chair up close to the window overlooking Winter Street as snow swirled in bright halos around the streetlamps and tree lights cast colorful dots onto wind-sculpted drifts. Snow-muffled church bells rang, calling the faithful to evensong at St. Peter’s, just a few blocks away. O’Ryan was stretched out full length on the carpet beside me, tummy up, eyes squeezed shut, a cat smile on his face, large yellow paws clutching a damp purple catnip mouse.

I’m Lee Barrett, née Maralee Kowolski. I’m thirty-one, red-haired, Salem born. I was orphaned early, I married once, and I was widowed young. I lived in Florida for ten years, and since I returned to Salem a few months back, my aunt Isobel Russell and I had been sharing the fine old family home on Winter Street . . . the same house where she raised me after my parents died.

I’d been working in television, one way or another, ever since I graduated from Emerson College. So far I’d been a weather girl, a home shopping show host, and even a phone-in TV psychic. That last gig, a brief stint at Salem’s cable station WICH-TV, was on a show called Nightshades. I dressed up like a Gypsy and, in between scary old movies, pretended to read minds, find lost objects, and otherwise know the unknowable. I’d been hired as a last-minute replacement for the previous host, Ariel Constellation, a practicing Salem witch who apparently could really do all that psychic stuff. Unfortunately, I was the one who’d discovered Ariel’s body floating facedown in Salem Harbor.

Not an auspicious start to a new job.

It didn’t end well, either. Ariel’s killer set a fire that pretty much destroyed the top two floors of our house, and if it hadn’t been for O’Ryan’s timely intervention, Aunt Ibby and I might not have been around to celebrate Christmas.

After the unpleasant publicity, Nightshades was canceled, and I was once again unemployed. An inheritance from my parents had left me well enough off financially, so I didn’t need to work at all. Being between jobs wasn’t a problem. I just prefer being busy.

On a positive note, I was sure that when my sixty-something, ball-of-energy aunt got through redesigning the entire upstairs and driving contractors and decorators nuts, the upper stories of the house would once again be livable and we could stop tripping over paint cans, fabric samples, and wallpaper books.

I angled the wing chair a little to the right so that I could watch for headlights rounding the corner onto Winter Street. Not just any headlights. I was hoping for a Christmas night visit from a special friend. Well, maybe Detective Pete Mondello had become quite a bit more than just a friend—but I was trying to move slowly in that area of my life.

My aunt Ibby appeared in the doorway, bearing a tray with two chintz-patterned cups and a matching teapot.

“You and O’Ryan certainly look comfortable. Ready for a spot of tea?”

“Sounds good,” I said, returning the chair to its original position. “I was just enjoying watching the snow. It’s been a long time.”

“Too long.” She placed the tray on the antique drum table between us and sat in the wing chair facing mine. “And at last you’re home for Christmas.”

She filled our cups with fragrant jasmine tea, and we tapped them together in a toast.

“Here’s to the end of a strange year,” she said. “And let’s hope that the next one is a lot less stressful.”

“Amen,” I said. “I’ll drink to that.”

Aunt Ibby smiled and gestured toward the sleeping cat. “Looks as though O’Ryan is enjoying his Christmas mouse.”

O’Ryan opened one eye and rolled over, still hugging the mouse.

“He loves it,” I said. “And he seems to have quite a catnip buzz going on.”

“Pete will be pleased that his gift was such a big hit,” she said. “Too bad he couldn’t have joined us for dinner.”

We’d had the usual holiday house full of relatives and friends for the festive meal, but the gathering snowstorm had sent them all home early.

“He said he’d try to stop by later.”

“I’ll bet a little snow won’t keep him away,” she said with a knowing smile.

I turned my chair just enough so that I could still see the headlights on any car turning onto Winter Street. It wasn’t often that Pete had a holiday off, and this year he’d had to choose between Christmas Day and New Year’s Eve. We’d already exchanged Christmas gifts. I hadn’t wanted to give him anything too personal at this early stage of our relationship, so I’d decided on a pair of tickets for good seats at an upcoming Bruins hockey game. His gift to me, a vintage brooch with an oval miniature painting of a yellow cat, was pinned to the deep V-neck of my white silk blouse. I wore dark green velvet jeans and had tucked a sprig of holly into random red curls escaping from my attempt at a French twist.

“You know, Maralee,” Aunt Ibby said, “I have a very good feeling about the New Year. The house is coming along beautifully, and the fact that you’re going to start January with a good deed for the community is an excellent omen.”

“An omen?” I laughed. “Maybe you’ve watched too many episodes of Nightshades!”

My aunt was a recent, and still pretty skeptical, believer in things paranormal. We both had reason to know, though, that some things are just beyond our understanding. O’Ryan was an outstanding example of that. The handsome cat snoozing happily at our feet had once been Ariel Constellation’s pet . . . some say her “familiar.” As many folks in Salem will testify, a witch’s familiar is far from being an ordinary house cat!

She shrugged. “Well, omen or not, your volunteering to help out at the new school will be such a blessing for the students.”

“I hope so,” I said. “I’m looking forward to it.”

The Tabitha Trumbull Academy of the Arts was due to open at the start of the New Year, and I’d been invited to be a volunteer guest instructor. The school was located in the sprawling old building that had once housed Trumbull’s Department Store in downtown Salem. The store had been closed since the sixties and had been slated for demolition until government grants and a historical site designation saved it from the wrecker’s ball. Already dubbed “the Tabby,” the school would soon be bustling with the activities of aspiring dancers, poets, painters, actors, and, in my department, television performers and producers.

“Your mother and I used to go to Trumbull’s with your grandmother Russell when we were little girls,” Aunt Ibby said. “We loved it. There was a grand staircase to the second floor, with wide bannisters, which I always wanted to slide down.”

“Did you ever do it?”

“No, I never did.”

“Now that I’m officially a staff member at the Tabby, I’ll give you permission to slide whenever you want.”

O’Ryan’s ears perked up. He stood, stretched, and trotted toward the front hall.

“Someone’s coming,” Aunt Ibby said. “O’Ryan always knows before we do.”

She was right. The gleam of headlights glinted on the frosted windowpane as a car rounded the corner from Washington Square.

“It’s probably Pete,” I said. When the door chime sounded, I followed O’Ryan into the hall and opened the front door. Pete Mondello stood there, smiling, hatless, holding a huge poinsettia plant under one arm while fat snowflakes fell all around him.

“Brrr. Cold out there.” He hurried inside, pulled me close for a quick hug with his free arm, and stamped his feet on the woven rope mat. “Merry Christmas, Lee,” he said, tossing his coat onto a hook on the tall hall tree. “You look good.”

“You look good, too,” I said, brushing a snowflake from his dark hair. An understatement. He looked wonderful. “How was your Christmas?”

“Fun,” he said, bending to stroke O’Ryan’s head. “My sister’s kids had a ball opening presents.”

“So did O’Ryan,” I told him. “He had the wrapping off of his purple mouse before we were up this morning. He’s been playing with it all day. I think he’s still a little bit drunk. Come on inside and get warm.”

Aunt Ibby greeted Pete with a welcoming smile, a “Merry Christmas, Pete,” and an offer of pumpkin pie.

He patted perfectly flat abs, claiming he’d already eaten too much, wished her a Merry Christmas, and handed her the poinsettia.

“Thank you, dear. It’s lovely.” She placed the plant on the sideboard and stood back to admire the effect. “Pete, I was just telling my niece about the old Trumbull’s Department Store.”

“I’ve seen pictures of it,” he said, “but I’ve never been inside.”

“It was a beautiful store. All those gleaming hardwood floors and racks of the latest clothes, a great big book department, hardware and notions and linens and toys and jewelry and just about anything a person might want. There was a player piano on the mezzanine-floor landing, and a man in a tuxedo played the popular tunes all day. But I guess the old stores just couldn’t compete with the malls.”

“I’m sure it looks quite different now,” Pete said.

“I guess it must,” I said. “The school director, Rupert Pennington, says a lot of the old fixtures will be moved out by the time school starts. My classes will be in the old shoe department.”

“I always got my back-to-school shoes at Trumbull’s,” my aunt said, reminiscing. “I wonder if the old bentwood chairs are still there. Thonet, I think.”

“I’ve heard the city plans to reuse as much of the furniture and fixtures as they can,” I said, “and some of the things will go to auction.”

My aunt nodded. “Maralee, remember our handyman, Mr. Sullivan?”

I did. A big man, probably in his seventies. He was the neighborhood handyman, always available if we needed a fence repaired or a drain unclogged.

Aunt Ibby went on. “He and his son were working on taking some of the smaller pieces to a storage locker today.”

“On Christmas? How do you know that?”

“Mrs. Sullivan is one of my Facebook friends. They went to work right after dinner. She’s not pleased. She seems concerned about them working there after dark.”

“I remember being afraid to walk past the Trumbull building at night,” I said. “All the kids said it was haunted.”

“I’ve heard those stories, too,” Pete said. “Something about a lady in white in the upstairs window, strange lights flickering on and off, and a piano playing in the middle of the night. Down at the station they think it’s just a trick the Trumbull family used to keep vandals away. I know they could never keep security guards very long.”

A slight buzzing sound interrupted us, and Pete reached into his pocket for his phone. “Oops. Sorry. I’ll take this in the hall.”

When he came back into the room, his expression was serious. “Afraid I have to leave. Something’s going on at your new school.”

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

“Don’t know yet, exactly. Seems your Mr. Sullivan went down into the basement, and his son says he just disappeared. Never came back up the stairs.”

“Disappeared? How can that be?”

“I wouldn’t worry too much,” Pete said. “He probably just wandered off someplace when his son wasn’t looking. It’s a big building.”

“Mr. Sullivan isn’t the wandering type.” Aunt Ibby sounded a tiny bit indignant. “Just because a person is over sixty doesn’t mean he wanders.”

“I didn’t mean . . . I’m sure he’s safe somewhere.” Pete sounded apologetic. “That’s what I meant. Gotta go.”

“He’s an old friend of the family, Pete,” I said. “I hope he’s okay.”

“Mr. Sullivan was one of the first people to come over to help us after the fire,” Aunt Ibby said.

“Does Mrs. Sullivan know that he’s missing yet?” I wondered aloud.

“I’m sure her son must have told her. I’ll call you just as soon as I know anything.”

I walked Pete to the front door, with O’Ryan tagging along behind, carrying the catnip mouse by one damp and tattered purple ear.

Pete shrugged into his coat, then reached into an inside pocket. “Oh, I almost forgot. I have another little gift for you.”

“Another one? What is it?”

“Sorry it’s not wrapped,” he said, handing me a small book.

I read the title and laughed. “The Official Nancy Drew Handbook. Just what I needed!”

“I don’t want you to fall behind in your studies just because school’s out for the holidays.”

When Pete and I first met, he thought I was just being nosy, because I asked so many questions about police work. That was when he’d started comparing me to that famous girl detective. Later, though, when he found out I was really interested, he convinced me to take an online course in criminology. I’d just begun, while Pete was in his third year of the same course, and I’d become more fascinated with his job than ever.

“I promise to study,” I said with a smile.

“Good,” Pete replied. “There’ll be a quiz later.”

“I look forward to it.”

After a quick kiss, he went out into the snowstorm, which was gathering intensity. The big, soft snowflakes that had been falling earlier had been replaced with the hard, stinging kind.

He should have worn a warm hat. And mittens.

The cat and I returned to the living room, and I looked around for Aunt Ibby. Her voice came from the den, which housed her computer, printer, fax, and other technical toys. She looked up from her phone when I entered the room.

“Of course I will,” she said into the receiver. “Don’t worry, dear. I’ll be right over to pick you up.”

“What are you doing?” I asked, although I knew exactly what she was up to. My busybody aunt was planning to brave the weather and drive the distraught wife to the Tabby.

“That was Mrs. Sullivan,” she said with an innocent smile. “She needs a ride to the Trumbull building. I told her I’d be right over.”

In this storm? I don’t think so.

“Aunt Ibby,” I said, “I know your Buick is a very safe car, but I doubt that the roads are all plowed yet. Driving in this storm just isn’t a good idea.”

“I told her I’d be there. And I will.” She stood and headed for the hall, then looked back at me. “Unless you’d like to drive?”

I’m not the best driver in the world, and I hadn’t had a lot of recent experience driving in snow, but my late husband, Johnny Barrett, had been a rising young star on the auto-racing circuit. I’d spent enough time around racetracks to know a little about handling cars.

Reluctantly, I agreed.

“Oh, thank you, Maralee. We’ll just pick up Mrs. Sullivan and dash right over to Essex Street.”

No dashing through the snow this Christmas night, thank you. Slow and steady. And prayerful.

It took only a few minutes to don coats and hats, boots and gloves, and to head out the back kitchen door toward the garage, where Aunt Ibby’s car was housed. By then the snow had acquired a gleaming frozen crust on top of a foot or so of wet base.

Great for snowball fights or building snowmen. Not so much for walking.

We crunched our way past the vegetable garden, where dried, white-coated cornstalks loomed like bent rows of arthritic ghosts and the winter-killed remains of tall sunflowers crackled under their coating of ice.

Aunt Ibby stopped suddenly. “Shhh. Oops. I thought I heard the cat door. O’Ryan, that nosy boy, has followed us.”

She was right. The cat raced past, skimmed along the snow, and sat in front of the garage.

“Go home, O’Ryan. Bad boy. Scat!” I pointed toward the house. “It’s too cold for you out here.”

Aunt Ibby pressed the garage door opener, and the cat trotted inside, looking back at us.

“Shall we take him with us?” Aunt Ibby asked. “I think he wants to come.”

I shrugged. “Sure. Why not? He likes to ride.”

She climbed into the passenger seat, and O’Ryan curled up on her lap. I eased the car out of the garage, and we headed slowly toward Bridge Street, where the Sullivans lived. Happily, Bridge Street had been plowed, and when we pulled up in front of the apartment house, Mrs. Sullivan was already waiting at the curb. A tiny little bird of a woman, she looked very small in the big backseat.

“Thanks so much, Ibby, and it’s so kind of you to drive, Lee, on such a dreadful night. I’m terribly worried about Bill. Junior sounds worried, too. It’s just not like Bill to go off and not tell anyone.” The thin voice broke.

Aunt Ibby murmured comforting words. I concentrated on the road as the windshield wipers tried to keep up with the icy droplets pinging on the glass. O’Ryan purred.

Even though Essex Street is practically around the corner from our house, Salem’s eccentric pattern of one-way streets and pedestrian malls made a roundabout route to Trumbull’s necessary. The plows had done a good job of clearing the main streets, though, and the trip wasn’t as bad as I’d expected. The parking lot next to the old store was nearly empty. There was one police cruiser, Pete’s unmarked Crown Vic, an old red van marked SULLIVAN AND SON with an attached U-Haul trailer, and a couple of other cars I didn’t recognize.

I parked as close to the building as I could, and we climbed out, leaving O’Ryan in the driver’s seat, peering out the window. There were lights on inside the building, and a uniformed officer stood outside the glass double doors. For as long as I could remember, those doors had been covered on the inside with some kind of thick fabric, preventing anyone from seeing in. All the display windows had been covered, too, but now light shone from each one and newly polished glass gave a clear view of the grand staircase Aunt Ibby had described. Pete Mondello stood just inside the door, in apparent conversation with a man who wore a black, velvet-collared topcoat and a gray fedora hat. I recognized Rupert Pennington, the new director of the Tabitha Trumbull Academy of the Arts. Mr. Sullivan’s son, Junior, sat on the bottom stair, his head in his hands.

Aunt Ibby spoke to the uniformed officer. “This is Mrs. Sullivan. She needs to talk to her son, to help you fellows figure out what’s become of her husband.”

The officer tapped on the glass and motioned to Pete, who held up a finger, signaling, “Wait a minute,” then, seeing us standing outside, quickly approached the double doors. He frowned as he pulled one of them open . . . not a grouchy frown, but one that meant “What the hell are you doing here?”

Pete stood in the open doorway. “Lee? Ms. Russell? What’s going on?” He caught sight of the woman with us. “Is this Mrs. Sullivan? Please come in, ma’am. I’ve been trying to call you.”

He bent to take Mrs. Sullivan’s elbow and guided her toward the stairs where Junior sat. His cop face firmly in place, he turned and spoke to us over his shoulder. “You two can come in. Can’t leave you standing out in the cold. Don’t touch anything.”

So there we stood, as Aunt Ibby says, “Like a tree full of owls,” in the middle of that vast, nearly empty, hardwood-floored, retail time capsule, Trumbull’s Department Store. I looked around. There was very little not to touch.

Mr. Rupert Pennington, who stood nearby and was also carefully not touching anything, broke the awkward silence.

“Ms. Barrett? Is that you?”

“Yes, sir. Aunt Ibby, this is Mr. Pennington, the director of the school. Mr. Pennington, my aunt, Isobel Russell.”

The director carefully removed one gray leather glove, and we shook hands all around.

“We drove Mrs. Sullivan here,” I explained. “She’s terribly worried about her husband.”

“Ah, yes, indeed. The dear lady appears quite distraught.” The director’s voice was clearly that of a trained stage actor. I’d met Mr. Pennington before, when I was first approved by the board to be an instructor at the Tabby, so I wasn’t surprised by his Shakespearean tone. I could tell by Aunt Ibby’s expression, though, that she didn’t know whether to be impressed or amused.

“How did you happen to be here on this dark and stormy night, Mr. Pennington?” my aunt asked.

“The young constable there”—he waved in Pete’s direction—“asked me to come and perhaps be of some assistance.” He reached into his overcoat pocket and produced a jangling ring of keys. “Apparently, I possess the only extant complete set of keys to this little kingdom.”

“Do you know if they’ve figured out where Mr. Sullivan might have gone?” I asked. “Whether he might have left the building for some reason?”

“Aha!” He’d replaced his glove and pointed his index finger into the air. “We traversed the perimeter of the main floor and unlocked each and every egress onto the street level. Not stepping outside, the officer examined the newly fallen snow to see if there were any footprints indicating that any person had recently exited the building.”

“And?” Aunt Ibby asked. “Were there?”

“Alas. Not a one. The only footprints were those at the front door, made by the missing gentleman and the strapping lad on the stairs”—he pointed at Junior—“as they went in and out, to and fro, so to speak, loading items into the truck.”

“Junior said his dad went into the basement,” I said. “Did you check the exits down there?”

Mr. Pennington shrugged. “There are none. It was explained to me that the basement was never used as a sales area for just that reason. No exits. Unsafe in case of fire, you know. So it’s just a storage place. The school can’t use it for classrooms yet, either. But someday, with sufficient funding, we’ll make it into a state-of-the-art sound and lighting studio. But for now, it’s a huge expanse of wasted space.”

“It’s like one of those ‘locked room’ mysteries,” Aunt Ibby said. “As in ‘Colonel Mustard did it in the library with the candlestick.’ What’s down there?”

“Mannequins,” he said. “Rows of mannequins. Men and women; boys and girls; headless torsos; assorted arms, legs, hands, and feet; various heads and other body parts. All naked, of course, but discreetly covered with sheets, each and every one.”

“That must be a strange sight,” Aunt Ibby said. “But isn’t the city going to sell the mannequins along with the other old fixtures? Perhaps that’s why Bill Sullivan went down there.”

“Originally, that was the plan,” he said. “But the costume division of the Theater Arts Department asked if they could have them, and the city agreed.”

“So we still don’t know why he went into the basement,” I said. “Maybe he was just curious.”

“Sorry to keep you people standing here.” It was Pete with a sobbing Mrs. Sullivan at his side. “Lee, maybe you and your aunt could talk to Mrs. Sullivan for a minute to help her calm down.”

“Well, certainly.” My aunt put an arm around the woman’s quaking shoulders. “Could you find her a chair, Pete? And maybe a glass of water?”

Rupert Pennington, looking distinctly uncomfortable, backed away from Mrs. Sullivan, whose loud sobs were interspersed with hiccups. “I’ll get a chair. There are still quite a few in the old shoe department.” He hurried away toward the staircase, motioning to Junior, who still sat at the foot of the stairs. “Come along, young man. We’ll get a chair for your poor mother.”

“Pete,” I said. “I have some bottled water in the car. I’ll get it. And would you mind if I brought O’Ryan inside? I didn’t think we’d be here this long, and it’s very cold out there.”

“You brought the cat.” It was a statement, not a question. But he couldn’t keep a straight face and broke into a half smile. “Sure. Why not?” He shook his head. “I’ll come with you.” He shrugged into his coat.

A wintry blast of air hit us as soon as we pushed the door open. He took my hand. “Watch it,” he said. “This sidewalk is getting slippery.”

He was right. With unsteady steps and short strides, we approached the Buick. The light from an overhead streetlamp showed O’Ryan stretched out along the top of the backseat. His pink nose was pressed against the glass, fogged from his warm, probably catnip-scented breath.

I unlocked the door, and O’Ryan, with a happy “mrrup,” hopped over into the front seat.

“Pete, there’s a six-pack of bottled water on the floor in back. I hope it hasn’t frozen. If you’ll grab a bottle, I’ll carry O’Ryan.”

“Do you always carry water in the car?”

“Yep. Ever since Aunt Ibby got caught in a three-hour traffic jam on Route 128 on a hot summer day.”

“Makes sense.” Pete stuffed the plastic bottle into his coat pocket, while I held the big cat against my shoulder with one hand and Pete’s steadying arm with the other. Still walking gingerly, we approached the old store. O’Ryan suddenly shifted his position, and I grasped him more tightly.

“Hang on, boy,” I said. “We’re almost there. Stop wiggling. You won’t like it if I drop you into a snowbank.”

“Mrrow,” he said and, poking his head over my shoulder, strained to look up at the roof.

“Do you think he’s looking for the top-floor ghost?” Pete teased. “You keep telling me he’s a witch’s cat.”

“Well, he is. He can’t help it.” I let go of Pete’s arm and looked upward, too. “Is that where the ghost is supposed to be? On the top floor?”

“So they say. But what town in New England doesn’t have a lady in white haunting a house or two? That story must be number one on the urban legend list. Crazy, isn’t it?”

“Uh-huh,” I agreed. “Absolutely crazy.” I grasped his arm again, a little more tightly.

I still don’t like walking past this place at night.

Even after we were back inside the Tabby, I held O’Ryan in my arms. If a big man like Bill Sullivan could disappear in there, how hard would it be to find a wandering cat? Aunt Ibby and Mrs. Sullivan were each seated in vintage bentwood chairs. Pete handed the water to the no longer sobbing, but still sniffling woman and after a moment, speaking in low tones, led her back toward the stairs.

With O’Ryan curled up on my lap, I sat in the vacated chair. Junior Sullivan and Mr. Pennington stood a few feet away, in conversation with the uniformed officer, who had come inside and was stamping his feet and blowing on cold-reddened hands.

“Mrs. Sullivan seems better,” I said. “What made her start crying so hard? She sounded almost hysterical.”

“They asked her if she and Bill were getting along. She thought they made it sound as though he was running away from her.”

“Well, I guess it’s a fair question. Were they? Getting along, I mean?”

“That’s what made her cry so,” my aunt said. “Seems they’d had a little tiff about him leaving home to come here on Christmas Day. Junior’s wife was upset about it, too, so the whole family was squabbling the last time she saw him.”

“I don’t see a man like Bill running off over a little thing like that.”

“She doesn’t,. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...