- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

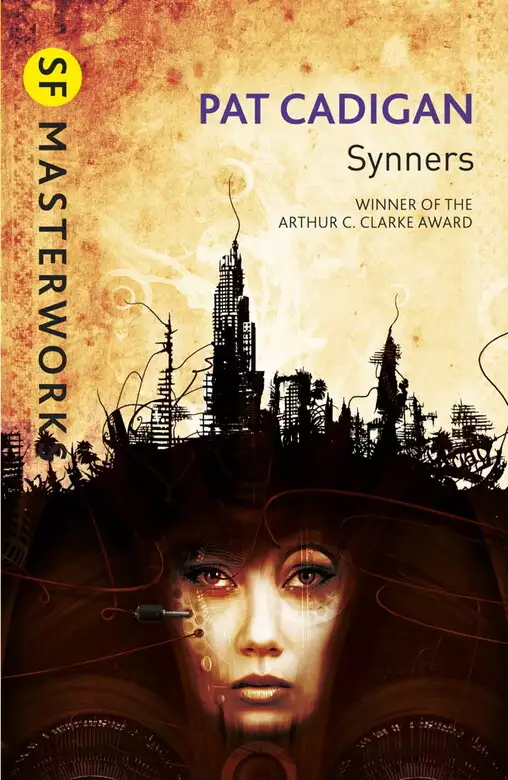

In Synners, the line between technology and humanity is hopelessly slim. To be a Synner is to join the online hardcore, an outlaw band of hackers, simulation pirates, and reality synthesizers hooked on artificial reality and virtual space. Now you can change yourself to suit the machines - all it costs you is your freedom, and your humanity. Synners shows us a world perilously close to our own. A constant stream of new technology spawns new crime before it hits the streets, and the human mind and the external landscape have fused to the point where any encounter with "reality" is incidental. Equal parts thrill-ride and cautionary tale, this classic novel by the Queen of Cyberpunk offers us a terrifying glimpse into the future of our race. Winner of the Arthur C. Clarke Award for best novel, 1992

Release date: October 1, 2012

Publisher: Gateway

Print pages: 497

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Synners

Pat Cadigan

‘He was looking at himself in the mirror in Medical’s bathroom, turning his head from side to side. Just as they’d said, he didn’t look any different. Same old head, only now it had eight holes in it, eight holes to be filled with eight plugs and a small menu of commands he could use to manipulate the images in his head.’

The person plugged into the computer, physically connected, tied and yet, paradoxically, set free to range through a whole new universe within, is one of the most potent and lasting ideas to come out of the branch of science fiction labelled cyberpunk.

Although now, with our addiction to constant mobile communication, the connection would surely be wireless, beamed from any point to a chip in the brain, still the image of the computer jockey tethered to the machine has a visceral power, more so than any more realistic invisible chains. The eight snaky wires described in Pat Cadigan’s novel also evoke the neural pathways inside the head, suggesting their potential for being remodelled and remade by input from outside – from others.

Because connection with other minds is surely the point – plugging into a machine not just to play games or wallow in porn, not just to leave ‘the meat’ behind while indulging escapist fantasies, but to communicate with others on a more intense and meaningful level – to share your deepest self with a loved one without the usual limitations and misunderstandings imposed by language. This is the old dream of empathic powers given a freshly convincing technological spin.

‘Once again words failed him. Like some kind of bad joke. He had goddamn sockets in his head to send out any thought at the drop of an inhibition, and he couldn’t manage to tell the person he’d just spent the night with what he was doing there.’

Synners had its origin in a short story titled ‘Rock On’, published in Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology, Bruce Sterling’s 1986 round-up of those writers he considered to comprise a new movement in science fiction through their ‘allegiance to eighties culture’. The only woman invited to join what otherwise seemed a boys’ club, Pat Cadigan was soon established as ‘Queen of the Cyberpunks’ (why is it that genres are blessed with Queens, but rarely Kings, unless his name is Stephen?).

Cadigan didn’t let her crowning go to her head. She continued to pursue her own vision, writing new technologies, but also about troubled, complicated people struggling with their lives; they are outsiders, and some of them are cool, and may even wear mirrorshades, but they live in a recognisably real world; there’s not a glamorous, body-modified prostitute-assassin among them. Synners is undoubtedly cyberpunk – I’d say it is, alongside the iconic masterpiece that is William Gibson’s Neuromancer, one of the defining works of that genre – but it is something more than a reflection of eighties culture; it speaks very much to our current situation.

Reading it now, more than twenty years after it was written, what strikes me most strongly about Synners is how it buzzes and pulses and brims with a sense of the future – and how very relevant and valid that future still feels in 2012.

It’s been said often enough that science fiction novels aren’t about the future, but about the time in which they’re written. Of course, it could hardly be otherwise; even the most determinedly ‘predictive’ and future-focused novel will reflect the contemporary hopes and fears of its author. The digital age was only just taking off when Cadigan was writing about it; two decades on, it is possible to see how prescient she was, and somewhat startling to realise that we are still only beginning to grapple with the problems she had guessed at. We agonise about spending too much time in imaginary worlds, and fear we’re losing touch with what matters in real life, even as that life is changing out of recognition; we worry (identifying with our computers) about being infected, being hacked, being cut off; and while artists and visionaries find ways of creating new wonders, others are exploiting them, with consequences that can never be predicted until it is too late.

Doing an online search for earlier fictional explorations of the mind-computer interface, I quickly realised this was no longer merely science fiction, but had become part of modern life. I read news stories about experiments demonstrating how people can be wired up to fly a helicopter by simply imagining they are moving a hand, a foot, or tongue. I read another report on research which had discovered the neural mechanism underlying the visual imagination, and learned that last year scientists used functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging to decode and reconstruct people’s visual experience of watching a short film. These and other experiments have already laid the groundwork by which the visions, dreams, daydreams or memories in one person’s brain can be read and recreated. Someone, somewhere, is working on developing the technology to make it possible to capture and transmit them from one brain to another. This technology may be available in twenty years – or ten – or . . .

Read Synners now, before it happens.

Lisa Tuttle

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE TENTH ANNIVERSARY EDITION

Which is to say, synthesisers, every sense of the word, and synthetics and artificial things, all manner of artificial things.

And the view changes from where you’re standing.

If you’d told me twenty-five years ago that the SF that would have got it most right, up to that point, was not Heinlein or Asimov or Clarke but J.G. Ballard and Philip K. Dick, I would not have laughed at you, just looked puzzled, just as I would if you had told me that the root form of millennial reality and millennial SF would be John Brunner’s The Shockwave Rider, which gave us viruses in the world computer before there were viruses, before there was a world wide web.

One of the functions, probably the most important function, of SF as literature is to describe the present to us under cover of describing the future, to explain our now to us in terms we can take by pretending to describe an imaginary soon. But sometimes older SF can describe our now to us better than it ever had a chance of doing when it first appeared.

There are artists who have made long and effective careers out of watching what was happening in the underground and out on the edge and then doing it for the public. You’ll find out more about that.

SF that catches the zeitgeist does that. Think Gibson’s Neuromancer, the first fugal strain of romance with the artificial, creating an imaginary space for the real world to move into and inhabit. And now retreating, further away, leaving us with a few words and ways of thinking, but little more.

Futures leave traces, like oxbow lakes tracing old river patterns.

The view changes, from where you’re standing.

Too often SF grinds slower now, coping with a future that already happened. Today’s technology (said Samuel R. Delany) is tomorrow’s handicraft; and we’re less and less certain where the edges and the borders are. Today’s hard news stories were yesterday’s dystopian SF.

Rereading Pat Cadigan’s fine, fast novel Synners, I was struck by how much the novel had changed since I first read it, a decade ago, as a judge for the Arthur C. Clarke Award (it won). The words, of course, have not changed. But the frame around the artwork has changed so completely that the artwork itself has softened and flowed like a Dali watch. Same landscape; different view.

Back then, the future that Cadigan described was edgy and out there and perfectly strange, a torrent of overload, predictive and cautionary. Back then, even antiviral software was an SF notion. Back then, it seemed like the whole thing was speculative fiction, was science fiction, was scientifical fabulation.

And, looking back, I realise my memory has been corrupted. After all, when Cadigan was writing, there were no search engines. You couldn’t set the web to send you the news you were interested in. There were no email viruses, no Trojan horses. That was back before Jerry Springer gave us scream porn, before COPS gave us poverty porn and crime porn.

This was back in the days of technology, before it had crashed into handicraft. Synners attempts, and in the main succeeds, in fusing a dozen different things into a portrait of a now in which rock videos and information and viruses and plug and play braintech and AI and all the porns and corporate observation and people are all beginning to interface into something liminal and numinous and street.

I don’t know how relevant it is any more to 1991, what it said to us then, but I know it says a hell of a lot about 2001.

Pat Cadigan predicts and describes and shapes and – most importantly – synthesises, and she calls it as she sees it.

The view changes from where you’re standing.

Or to put it another way: if you can’t fuck it, and it doesn’t dance, eat it or throw it away.

Neil Gaimanin transitJuly 18, 2001

1

‘I’m going to die,’ said Jones.

The statuesque tattoo artist paused between the lotuses she was applying to the arm of the space case lolling half-conscious in the chair. ‘What, again?’

‘Don’t laugh at me, Gator.’ Jones ran a skeletal hand through his nervous-breakdown hair.

‘Who’s laughing? Do you see me laughing?’ She shifted on her high stool and held her subject’s arm closer to the lamp. The lotus job was especially difficult, as it had to merge into a pre-existing design, and her eyes were already strained from a full night’s work. ‘I don’t laugh at anyone who dies as often as you do. You know, someday your adrenal system is gonna tell you to fuck off, and you won’t be back. Maybe someday real soon.’

‘Just as well.’ Jones turned from the skull-and-roses design he’d been looking at pinned to the wall of the tent. ‘Keely’s gone.’

Gator lifted the needle and dabbed at the decorated flesh, frowning. The cases on the Mimosa generally had terrible skin, but they were docile enough to make a good filing system, considering you could usually find them wherever you left them – they didn’t move around much on their own, and unlike other kinds of hardcopy, they seldom got stolen. ‘What did you expect? Living with someone who keeps dying on you is bound to strain any relationship.’ She looked at him with large green eyes. ‘Get help, Jones. You’re an addict.’

His bitter smile made her look down at the lotuses again quickly. ‘Jones and his jones? Yah, I know. I don’t care. I got no complaints about that, not one. If I’d had to go one more day with that depression, I’d have killed myself anyway. One time, for good.’

‘I hate to point out the obvious, but you’re depressed now.’

‘That’s why I’m going to die. And Keely didn’t leave me. He’s gone.’

The tattoo artist paused again, resting the flabby arm on her knee while she re-inked the needle. ‘Is there a difference?’

‘He left a note.’ Jones fished a scrap of paper out of his back pocket, uncrumpled it, and held it out to her.

‘Bring it over here and put it under the light for me, I’ve got my hands full.’

He did so, and she studied it for several long moments. ‘Well?’ he demanded.

She pushed his hand aside and bent over her subject’s arm again. ‘Shut up for a minute. I’m thinking.’

There was a sudden blast of music from outside as the jammers who had been thrashing all night went at it again. Jones jumped like an electrified chicken. ‘Shit, how can you think with all that?’

‘Can’t hear you over the music.’ Nodding her head to the beat, she finished the lotus and set the needle on the tray. One more flower, and then she could stick the case back under the pier he’d come out from. She straightened up, pushing at the small of her back. ‘If you’re really going to die on me, you could at least rub my neck before you go.’

He began kneading her shoulders. The music outside lessened in volume, receding up the boardwalk. Someone was mounting a hit-and-run; have fun, kids, call if you make bail.

A tall man in an ankle-length cape burst through the tent flap, startling Jones again.

‘Ow!’ Gator slapped Jones’s hand off her shoulder. ‘Jesus, what are you, a Vulcan?’

Even if Jones had understood the old reference, he wasn’t paying attention. He was staring at the black patterns writhing on the white material of the cape, strange intricate waves dividing and subdividing almost too fast for the eye to follow, seeming to implode as they swept along the surface.

‘Nice,’ said Gator, wincing as she rubbed the spot Jones had pinched. ‘Who’s your tailor? Mandelbrot?’

The man turned his back and spread the cape wide. ‘Could you just die for this, or what?’

‘Bad choice of words,’ Gator said darkly. ‘And if you’re here on my account, forget it. I don’t do skin animations.’

‘Actually, I was looking for someone.’ He swept over to the case slumped in the chair and bent to peer at his face. ‘Nope. Oh, well.’ He straightened up, giving the cape another swirl. It was pulsing with moirés now. ‘Hit-and-run in Fairfax, if you’re interested.’

‘Fairfax is a hole,’ Gator said.

‘That’s why it needs a party.’ The man grinned expectantly.

‘Yes, I do know who you are,’ she added, as if in answer. ‘And I’m charmed as all get-out, but as you can see, I’m booked.’

He looked from the case to Jones, who was still transfixed by the cape. ‘You Mimosa people are a strange bunch.’

‘You should know,’ she said.

‘Last call. You sure?’ He leaned in a little. ‘Kiss me goodbye?’

She smiled. ‘Dream about it.’

‘I will. I’ll put you in my next video.’

‘Valjean!’ someone yelled from outside. ‘Are you coming?’

‘Just breathing heavily,’ he called back, and swept out in swirling clusters of slithering paisleys.

‘Keep rubbing. Nobody gave you the night off yet.’

Obediently Jones went back to massaging her neck and shoulders. The music had faded away, leaving them in relative quiet. Somewhere farther down the strip, someone began improvising something in a high minor key on a synthesizer.

‘What I think,’ she said after a bit, ‘is you should make your peace with the Supreme Being, however you may conceive of it. Full church confession.’

Jones gave a short, harsh laugh. ‘Oh, sure. Saint Dismas could really help me.’

‘You never know.’

‘I’m not of the faith. I don’t belong.’

‘You do now. I’d say you definitely qualify as incurably informed. Let me see Keely’s note again.’

He gave it back to her, and she read it over as he worked his fingers up her neck to the base of her skull. ‘“Dive, dive” could only mean—’

‘I know what it means,’ she said. ‘“Divide, the cap and green eggs over easy, to go. Bdee-bdee.” The “bdee-bdee” is a nice touch, actually.’

Jones laughed again. ‘Yah, sure is. Keely’s the one who needs help, not me. That B&E shit. I told him someday he’d get caught. I told him. And I begged him to get help—’

‘The same kind of help you got? Implants from some feel-good mill that doesn’t give a shit as long as your insurance company comes across?’ She shrugged away from him and went to a small laptop on a table in the corner of the tent. The intricate climbing ivy pattern displayed on the screen was rotating through a sequence of views from different angles. She danced her fingers over the keyboard. The ivy pattern grew several more leaves. She pressed another key; the screen partitioned itself into two halves, scooting the ivy over to the right. A menu appeared on the left.

‘I’ll see what anyone knows,’ she said, touching a line on the menu with her little finger. ‘Eat that note.’

‘I don’t like to die with anything in my stomach.’

She sighed but didn’t answer. On the left half of the screen, the menu had been replaced by the legend, Dr Fish’s Answering Machine in large, plain block letters. One-handed, she typed the word tattoos on the screen.

U/1 or d/1? came the response.

U/1, she typed, and after waiting a moment she pressed one more key. The partition line in the center of the screen disappeared as the design was uploaded and the two halves merged into one. The rotating ivy froze and then faded away.

The doctor thanks you for your patronage and reminds you to eat right, get plenty of rest, detox regularly, and consult your physician before beginning any exercise program.

She reached for a cigarette as the screen went blank. ‘Nobody knows a thing,’ she said. ‘I’ll find the answering machine tomorrow and see if—’

There was a soft thump behind her. Jones had keeled over on the packed sand, dead. She groaned. ‘You shit. You actually did it, you piece of useless fucking trash. I should just dump you. I would dump you, but Keely would care. God knows why.’

She turned back to the laptop and called up the stored copy of the skull-and-roses pattern Jones had been looking at earlier. Interesting how he’d been drawn to that one. It supported her theory that everyone had one special tattoo – at least one – applied or not. Of course, the way things were with him, he might simply have been drawn to the skull, but she had other designs that suggested death far more strongly than that one, and he’d barely noticed those.

Partitioning the screen again, she called up the email menu and prepared to upload the skull-and-roses pattern. She added a short-form letter:

Here is the latest design in your subscription to the Tattoo-of-the-Month Club. We ask that you pick it up at your earliest convenience, and that you consult your physician before skin integrity is compromised.

She pressed the upload key and waited. The screen blanked again except for a small square blinking in the lower right-hand corner. Minutes passed. She left the buffer open and went over to the case in the chair. He was passed out or asleep. She pulled him out of the chair and stretched him out near the entrance. In a little while the kids would show up looking for eat-money; she could pay them to drag him back to his usual spot under one of the piers. Then she hefted Jones into the chair and bared his left arm.

Maybe she ought to give him the skull-and-roses just to make him feel better, she thought, and then decided against it. If he was choosy, let him pay for the privilege. She remembered him when he’d gone from trying to crack video to just being a hanger-on, the type who basically helped you get toxed. The only difference between him and someone like Valjean, was Valjean had managed to stay detoxed long enough to put together a decent band. Or maybe she was just feeling pissy because she’d had the inclination to pick a vocation that required her to do it sober.

The laptop beeped discreetly, and she went back to it.

On my way. The words blinked twice and then vanished. She recalled the ivy pattern, sized it, and set it to print out. The small cube-shaped printer spat a narrow strip of paper at her. She took it to Jones and pressed it down on the inside of his forearm, smoothing it against his flesh with two fingers. A minute later she peeled the paper away and looked at the ivy design on the pale skin. Perfect offset. She picked up her needle.

The tent flap opened, and two kids came in. She knew the husky fifteen-year-old, but his skinny friend must have been a recent arrival. Didn’t look a day over twelve. Getting old, she thought.

‘Put him back where you got him,’ she said, pointing at the case on the ground. ‘And if you can’t, remember where you end up sticking him so you can tell me exactly.’

The big kid nodded.

‘And then don’t get lost,’ she went on. ‘I’ll need you to load this one for a friend.’ She gestured slightly with Jones’s arm.

The kid took a step forward and squinted at Jones dubiously. His friend crowded behind him, looking from her to Jones and back with large, frightened eyes. ‘Scan him flat,’ said the big kid.

‘He was dead, he’s just comatose now.’

‘Whack it for a mark.’ He pointed at the designs.

‘You’ll do it out of the kindness of your heart,’ she laughed. ‘We’ll talk tattoos later. Much later.’

He lifted his chin belligerently. ‘Hey, I’m packed. Whacked two yesterday.’

‘Honey, what I’ve forgotten about finding floating boards it’ll take you the rest of your life to learn.’

He looked over at the laptop covetously. The ivy design was rotating on the screen again. ‘Mark me?

‘It’s spoken for.’

His round face puckered sullenly. ‘N.g. to leave the cap off,’ he said. ‘Someone could crash the party.’

‘And someone who hacks me could find the doctor is in.’ She gestured at the case. ‘Just return my file for me and stick around, and then we’ll discuss it. In English, please, I don’t talk your squawk. I’m not going to stone you. I never have, have I?’

He pointed at Jones. ‘That’s a stone.’ He and his friend each grabbed a leg and dragged the case out of the tent.

Kids, she thought, starting on the ivy. She had it mostly done by the time Rosa showed up.

2

The real stone-home bitch about night court was having to stay awake for it.

Sitting at the back of the well-populated courtroom, jammed between some fresh-face named Clarence or Claw and a null-and-void wearing a bail-jumper’s Denver Boot, Gina tried to calculate her immediate prospects. Hit-and-run – probably fifty, since she’d only been an attendee, not a conspirator; a hundred if the judge got stoked by the time her turn rolled around. Possession of controlled substances would be another hundred. Public intoxication, disorderly conduct, failure to report a hit-and-run, trespassing, and resisting arrest – call it a hundred and fifty, red-eye special rate, possibly two hundred. The resisting charge was a stone-home joke, as far as she was concerned. She’d only run, she hadn’t swung on anybody once she’d been caught. Like it wasn’t natural to run like hell when a hyped-up battalion of cops came at you.

Fuck it, what difference did one more charge make, anyway? The fines would clean her out and then some, one more garnishment on her wages, so-fucking-what. All she cared about now was getting back on the street so she could find Mark and take him home. Stupid burnout had let himself get dragged off without a second thought again, and here she was paying the price for it. She wouldn’t have been at the goddamn hit-and-run in the first place if she hadn’t been looking for him.

She’d started out on the Manhattan-Hermosa strip, what the lads called the Mimosa, part of the old postquake land of the lost. She wasn’t old enough to remember the Big One, hadn’t even been living in the big C-A when it had hit. The kids who shanked it on the Mimosa didn’t remember the quake, either. For all they knew, the old Manhattan Pier and Hermosa Pier and Fisherman’s Wharf had always stretched out over dry sand, just to shelter the space cases who squatted under them. Some of the cases probably remembered the Big One. Probably not as many as claimed to.

The piers shouldn’t have survived the Big One (which everyone was now saying hadn’t been the real Big One after all, just the Semi-Medium One, but that didn’t scan as well). Except for part of the old Fisherman’s Wharf, though, they were still standing. Not in prima shape, but standing. Not unlike Mark.

Living through the quake and the postmillennial madness that had followed was one way to end up under a pier talking to your toes; taking some of the stuff available on the Mimosa was another. Mark had always been a candidate for a spot in the sand, even back in the early days before all the hard party-time he’d put in had really begun to take its toll. Sometimes she could almost let the fucking burnout go ahead and flush himself down the rabbit hole in his brain. Like someone had said years ago, some of us can cut the funk, and some of us can’t.

But she wasn’t ready to let him slip away. Whether he was still salvageable or not, whether he was even worth the trouble, she couldn’t bring herself to say fuck it and let him go. So she did another night on the Mimosa, poking into shacks and lean-tos, searching under piers, checking out the jammers and scaring off the Rude Boys, looking to take him home, hose him down, and detox him enough to get him through his corporate debut the day after tomorrow.

Several of the regulars had said they’d seen him hanging with a hit-and-run caravan headed for Fairfax. Toxed to the red line, no doubt. The stupe didn’t even like hit-and-runs, but someone had probably said party-party-party fast enough to blank out any other thoughts, someone like Valjean and the rest of his no-account band. Like any of them needed to play hit-and-run in the Fairfax wasteland.

She’d ripped over to Fairfax as fast as the toy engine in the little two-passenger commuter rental would allow. The fancy rubble of the old Pan Pacific Auditorium had been hard alive and jumping by the time she made it, bangers and thrashers and the pickle stand in business while the hackers ran fooler loops on their laptops to confound surveillance. All the usual crowd you’d find at an illegal party set up fast in a public place, but Mark had already floated off somewhere else, if he’d ever been there at all. Before she could get a new line on him, the cops had come in and busted things up.

She had almost sulked herself into a doze when most of the crowd that had been waiting ahead of her rose en masse to stand before the judge. To Gina’s right a guy with a handcam climbed over two rows of seats for a better angle.

‘Another clinic?’ the judge said wearily, glancing at the monitor on her bench.

‘Three subgroups, Your Honor,’ said the prosecutor. ‘Doctors, staff, and patients.’

‘At this hour?’ The judge shrugged. ‘Oh, but of course. Doctors never keep regular hours. And if you weren’t operating round the clock, some of your patients might reconsider. I wish you people would perpetrate insurance fraud in some other jurisdiction. Like Mars. Priors?’

‘We’ll get to that, Your Honor,’ said the prosecutor hurriedly as a few hands started to go up.

Gina sat forward, her fatigue momentarily forgotten. Insurance fraud wasn’t exactly the kind of thing that called for a raid in the middle of the night. The litany of charges was boring enough: conspiracy to commit fraud, fraud, unnecessary implantation procedures – the usual for a clinic that put in implants under pretense of treating depression, seizures, and other brain dysfunctions. Just another feel-good mill, big fucking deal. She started to drift off.

‘. . . unlawful congress with a machine.’

Her eyes snapped open. A murmur went through the courtroom, and somebody smothered a giggle. The guy with the handcam had climbed over the spectators’ rail and was panning the group carefully.

‘And what, Mr Prosecutor, constitutes unlawful congress with a machine?’ the judge asked.

‘It should come up on your screen in a moment, Your Honor.’

The judge waited and the court waited. Several long moments later the judge turned away from the monitor in disgust. ‘Bailiff! Get downstairs right now and inform central we’re having technical difficulties. Do not call. Go, physically, and tell them in person.’

Next to Gina, Clarence or Claw gave a loud, showy, fake sneeze. The judge banged her gavel. ‘We can cure the compulsively comedic here, you know. Six months for contempt may be old-fashioned aversion therapy, but it works, and we don’t have to bill your insurance company, either.’ The judge’s glare fell on the prosecutor. ‘You have been warned repeatedly about inputting evidence and confiscated material without following proper decontamination procedures.’

‘The procedures were followed, Your Honor. Apparently they need updating.’

‘Who was responsible for the storage of this data?’ the judge asked, surveying the group sternly. A hand went up timidly from somewhere in the middle.

‘Your Honor,’ said the defense attorney, stepping forward quickly. ‘Data storage personnel cannot be held responsible for viral contamination and spread. I cite Vallio vs. MacDougal, in which it was determined MacDougal had no culpability for an infection that may have already existed.’

The judge sighed. ‘Whose data was it, then?’

‘Your Honor,’ said the defense attorney, even more quickly, ‘the owner of the data cannot be cited without establishing—’

The judge waved the woman’s words away. ‘I get it, I get it. Viruses form all on their own, input themselves without a human agent, and nobody’s ever responsible.’

‘Your Honor, even leaving aside the issue of self-incrimination, it’s very hard these days to prove that any virus in question was not pre-existing and inert until triggered by—’

‘I’m familiar with the problem, thank you very much, Ms Pelham. This doesn’t alleviate the immediate situation.’

‘Move for a recess, Your Honor.’

‘Denied.’

‘But the virus—’

‘Counselor Pelham,’ the judge said wearily, ‘it may come as a shock to people of your generation, but courts were not always computerized, and it was not only possible but routine to conduct business without being online. We will continue, using hardcopy as needed; that is why we maintain court clerks and court reporters. I still want to know what this “unlawful congress with a machine” charge is s

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...