Sweet Sorrow

- eBook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

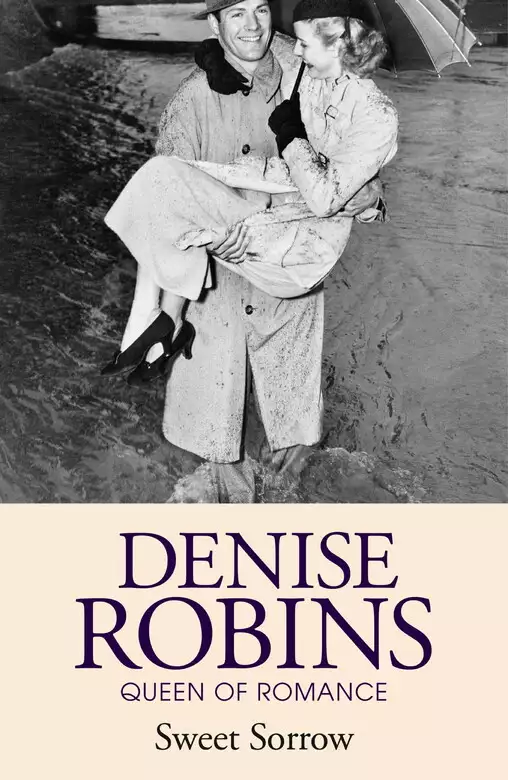

Fate throws them together ? a disastrous flood, an isolated stone house, a handsome and successful surgeon, and a lovely young girl. He saves her life ? and steals her heart ? as the floodwaters advance on their little refuge. When the waters finally recede, Celia knows that dashing Guy Denver is her life?s only love. And Guy ? though married to a woman who will never set him free ? returns her passion, but his sense of honour will not let him speak. Will the sweets of sorrow soon turn to bitterness? or love fulfilled?

Release date: February 27, 2014

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Sweet Sorrow

Denise Robins

He was driving in the direction of Lincolnshire. He had no clear idea where he was going. As much as possible, he chose the quiet by-roads with little traffic. Sheer exhaustion had made him stop for lunch at a small pub, then carry on, mile after mile—mile after mile. Now at four o’clock, darkness was falling. The grey January twilight blotted out the landscape slowly but surely and it had been raining persistently for some time. Guy Denver pulled up his car, felt for his pipe and lit it, then looked around him, conscious that the country was as dreary as his own soul.

On one side of him, there appeared to be marsh; damp, scrubby, low-lying land. On the other, he could see only sheep-walks and rabbit-warrens. Immediately before him a ridge of bold hills which looked through the rain as though concealed by a handful of blue chiffon.

Guy Denver pulled out a map. Where was he? He tried to trace his route, unutterably tired, eyes red-rimmed and sore. God, but he needed sleep! But even if he found a bed, he knew that he would not be able to sleep. He would only think:

“I’m a failure! A failure in my job. A failure with the woman I married …”

Dragging his thoughts back to the immediate present, he went on examining the map with the aid of the light from the dashboard. He came to the conclusion that he must be in the Fen district. No wonder it was damp and gloomy. He had reached those lowlands which adjoin the tidal reaches of the Trent and Humber. Those hills beyond must be the Wolds.

Guy put away his map. He sucked thoughtfully at his pipe for a moment. The best thing he could do was to get back on to the main road and find shelter for the night.

As he switched on the engine again, a gust of wind spattered great raindrops against the windscreen. He put the wiper into action. The steady droning of it against the glass only added to his gloom.

“Oh, damn, damn everything,” Guy Denver said to himself, miserably, and drove on until he reached a signpost. The rain was shortening the beam of his headlights. He could just manage to see the words:

“To Lyme Purgis.”

Guy had never heard of the place. No doubt it was a small hamlet. But it would probably have a pub in it. He would go on—to Lyme Purgis.

He covered another couple of miles, meeting nothing on the road. This was wild, lonely country. If he had wanted solitude, he had got it. But he wished the rain would stop. It made driving even more tiring than before and it was a narrow road. If he met anything as big as his own saloon, he would have some difficulty in passing it.

Suddenly he saw the dim yellowish light of a vehicle coming toward him. He pulled his car into the side of the road as far as he could get it, scraping the paint against a scrubbly hedge.

The lights on the other car were poor. And now the beam of his headlights threw up a narrow bridge just in front of him. Just as well he had stopped. If two cars met on that bridge they would block each other entirely.

Guy dimmed his headlights and watched the other car come on. From what he could see, it was a small two-seater—possibly a little Morris.

What was happening? The car faltered—seemed to stop. The lights wavered as though the driver was turning the wheel first in one direction, then in the other. Weary, and with his nerves on edge, Guy felt unduly irritated. He put his head out of the window and shouted:

“Come on! Come on!”

Then suddenly, the catastrophe! Something terrible which happened in front of Guy Denver’s very eyes. For the lights of the little car seemed to drop, and the car dropped with them. Simultaneously he heard a piercing cry. The cry of a woman.

Guy Denver’s heart leapt to his throat. He switched his lights full on and leapt out of the car. The rain drove against his face. He brushed the drops away with the back of his hand and stared before him. Then it was revealed to him that one of the piers must have been swept away. The bridge had tumbled in, and the car with it.

“God!” A cry of horror came from Guy’s throat. He began to run forward. The driver of that car had been a woman. And now she must be in the river—that river, which, swollen by the rains, was tearing across the marshland like a cataract.

With his heart in his mouth, Guy came to the edge of the bank and peered down.

Merciful heavens! What a piece of luck. The car was not in the water. It was suspended on the remains of the pier, sideways.

Guy, already soaked to the skin, but no longer tired, scrambled down the bank to the rescue. With some difficulty, in the darkness, he managed to get to that car. Equally, he thought, it was a mercy that it should have been an open car with a cloth-hood and talc side-curtains which were easily smashed in. A girl lay across the wheel, motionless. She appeared to be the one and only occupant. Breathing hard, Guy dragged the unconscious form out of the little car. He laid her on the bank and kneeling down beside her, placed a hand on her heart. He could not see her face clearly. It was a white mask, blotched with mud and rain. But he found that her heart was still beating. Thankfully, he wiped her face with his handkerchief, hoping that she would open her eyes. She did not move. He lifted one of her hands—a slim, cold little hand—and began to chafe it. His own feelings of misery and depression had evaporated. He was very much alive now, and concerned only with the condition of this woman. For all he knew, she might be seriously hurt. He must get her to shelter as soon as possible.

He stooped and, like a fireman, lifted the girl over his shoulder. She was not heavy. She was small and built on fragile lines. He wondered what the devil she had been doing driving alone through such desolate country at this time of night.

Reaching his saloon, he opened the back door, and placed the girl on the seat, with a folded rug for a pillow beneath her head. He switched on the roof light. Now he could see clearly the victim of the bridge disaster. Why, she was absurdly young—she could not be more than twenty or so. And lovely—yes—even in her bedraggled condition—hatless, lovely, fair silky hair, a tangled mass. Long black lashes spread like little fans on the pale cheeks. The oval nails on the slender fingers were pink and polished. She was rather shabbily dressed but her tweed suit was good. Guy Denver knew good tailoring when he saw it. She wore a leather motoring-coat over her tweeds and a green cashmere scarf. Bending over her, Guy loosened the scarf and patted her cheeks, wishing that she would recover consciousness. What in heaven’s name was he to do with her? This was a nice end to his day. The day on which he had walked out on all women—hoping he had finished with them—loathing the very thought of the sex, since the one woman had destroyed all his faith.

Well, the best thing he could do was to turn the car back and go back along the road whence he had come. He was forced to do so now since the bridge leading to Lyme Purgis had broken down.

The rain went on pelting—pelting. A piercing cold wind shivered through Guy despite his thick coat. He drew on his fur-lined gauntlets and climbed into the driver’s seat. The sooner he got this poor girl to an hotel, the better.

With difficulty, he turned the long car, then hot and tired began to drive quickly through the night. Now and again he looked over his shoulder at the silent passenger on the back seat. She made no movement.

“Concussion,” Guy Denver muttered to himself.

He reached the signpost which had sent him in the direction of Lyme Purgis. Now, which road should he take? Coming along for the last ten or fifteen miles, he had seen neither farms nor houses. He had better take that right turn. It must lead him to some sign of civilisation. What a fool he had been to drive right into the Fen country with which he was so unfamiliar, and in total darkness.

The next thing that would happen, he thought grimly, was that he would run out of petrol. The indicator on the dashboard showed that he was getting low.

Twice he got out of the car and stared around him. His heart began to sink and a real dismay shook him. God, what country! It was the lowest-lying marshland on either side. And there was water everywhere. The whole damn country seemed to be under water. He had heard that there were floods in the Fen district at this time of year. Well, it was a nice thing to find himself in the flooded part of the Fen country with an unconscious girl on his hands.

With a sensation of helplessness, Guy drove on. Then at last he saw a welcome light glimmering in the distance. He drove toward the light. It seemed to come from a dwelling down a narrow turning which was little more than farm lane, fringed with trees. Perhaps it was a labourer’s cottage. Well, no matter. He could not go on any further in the hopes of finding a pub. He might lose his way altogether and for all he knew that girl in the back might be seriously ill.

The big wheels of his car squelched and slithered a bit as he turned down the lane. The road was well under water here. Now and again his back wheels went round with a hissing noise, and he accelerated in vain. But he managed to reach the dwelling whence came that welcome beacon of light.

Jumping out of the car, Guy wiped his eyes with his handkerchief, went up to the door and knocked on it. It was a small grey-stone house—solidly built and of quite good type. Not, he imagined, a labourer’s dwelling. There was a well-kept little garden surrounding it and some trees at the back.

No answer to his knocking. He knocked again. Then impatiently pushed the door open. He found himself in a small lounge-hall which was deserted. Striding through it, he pushed open another door. Darkness here. He felt for an electric switch, then laughed at himself. No electricity here. That single light had come from an oil-lamp burning in the hall. He was certainly a long way from civilised London.

Raising his voice, he called out:

“Hi! anyone here?”

No answer. Only an uncanny silence. And now Guy Denver stared around him, puzzled, wondering if there was anybody in the place at all. He picked up the lamp from the hall and began to walk through the house. To his surprise he found it completely deserted. Whoever had been here, had apparently left in a hurry. In the living-room on an oak trestle table, there was a half-finished supper; some eggs, now cold and stuck to the dish. Bread, butter, ham and a big pot of coffee. The coffee was stone-cold which meant that the person or persons about to eat, must have left here sometime ago.

A coal-fire had obviously been burning, but had now gone out, so that the little house was intensely cold. The furniture was good old-fashioned stuff and there was every sign of comfort. No, it was no farm-labourer’s house. But it was very small—two rooms and a kitchen.

Guy Denver passed a hand across his forehead and blinked his eyes.

He wondered if he was in a nightmare. The whole thing was curiously unreal—even eerie. This unoccupied, deserted house … The stormy night … the shattered bridge … and that unconscious girl in his car.

Certainly fate had chosen a strange way of helping him to forget his own troubles. Everything that had happened in London receded into the background. He could think of nothing but his present predicament.

There was only one thing to do. He must carry his unknown passenger into this house and shelter here for the night.

It was long past eight o’clock. Four hours since he had taken that turning for Lyme Purgis. Four exhausting hours of battling with the darkness and rain and this sinister countryside.

Guy carried the girl into the house and shut the door behind him. In the living-room there was a sofa. He laid the girl on the cushions, then hunted for alcohol. If he could only find some brandy for her! He needed a drink for himself, too. Rummaging through cupboards in the kitchen, he was disappointed to find nothing but beer. That was all right for him, but not for his companion.

He went back to the sitting-room, took off his coat and knelt down by the sofa. He began to make more extensive examination of the girl. He had careful sensitive hands. And soon they discovered the wound on her head. A nasty jagged cut across the scalp on which the blood had congealed, matting the fair silky hair. Guy Denver nodded to himself.

“That’s it! Concussion, and as near thing as I have ever seen. It’s a wonder she was not killed.”

She was very pretty. What a perfect mouth! Faintly rouged, piteously open, showing small white teeth. A firm white chin with a cleft in it.

Guy Denver said to himself:

“I must do something about that cut on her head. If it isn’t attended to, it may mark her for life and that would be a pity for one so young and beautiful.”

He took the oil-lamp and walked up the narrow staircase to investigate still further. He found one large bedroom with a big old-fashioned double-bed in it spread with a white counterpane. On a high mahogany chest-of-drawers there was another lamp, which he lit. In the grate a fire was laid. Kneeling down, he applied a match to the paper and soon the dry wood was crackling. He must have warmth for that girl. He hoped he would find a hot-water bottle, too. She must have heat in her state of shock.

He would get her up here and wrap her in blankets. Then he would go downstairs, make up the kitchen-range which was still smouldering and get some boiling water. He must do what he could to that wound on her head.

Celia Hammond opened her eyes.

For a moment she thought that she was in her bed, at home, in Lincoln. And she had been having a nightmare—she had suffered from them since daddy died. But there was always old Mary, who had been her nurse and afterwards cook, to call for. Mary who would come in, soothe her, pat her hand and say: “Now Miss Celia, deary, it’s all right. You try to sleep again and I’ll sit by you ‘till you’re off.”

Celia’s eyelashes fluttered.

“Mary!” she called.

But it did not seem to her that she called very loudly. Her voice was only a whisper. Strange! And now she saw that she was not in her own bedroom at all. How very queer and frightening. She was in a strange room with a sloping ceiling, white-washed walls on which there were some unfamiliar pictures. Unfamiliar china ornaments on the mantelpiece, over which hung a big text:

“The Lord Is My Shepherd. …”

Celia, coming to consciousness more fully every second, felt her heart beat quickly. In heaven’s name where was she? She moved her head and a queer pain made her call out. She lifted her hands and found her hair concealed by strips of linen, forming a bandage like a cap.

Suddenly she saw a man come into the room. A slimly-built man in a woollen dressing-gown. He came quickly to the bedside and said:

“Ah! so you’re round at last.”

Celia stared up into his eyes, dazedly.

“Where—am I?”

“That, I can’t tell you,” he said with a short laugh, “for I’ve no idea myself. I’m about as lost as you are. But I can tell you how you came here. Do you yourself remember anything?”

Celia thought hard. She could remember leaving the house in Lincoln, yes. Setting out in the little Morris which she was going to sell in London. She had driven all day, then lost herself in the Fen country. She had approached the bridge and after that … no remembrance.

“I must have had an accident,” she said.

“You did,” said Guy Denver, and gave her a brief explanation of what had happened and of how he had pulled her out of the car and brought her here.

“So you see,” he finished, “we’re quite alone in this house. And it is quite deserted. I can’t tell you in the least who the place belongs to. But no doubt the owners will return to it tomorrow, and if you’re fit enough, I’ll try to get you to some hospital.”

“Oh!” whispered Celia, weakly, and suddenly became conscious that she was wearing masculine pyjamas much too large for her. How did she get into them? This man must have undressed her … who was he? But how frightful …! The hot colour tore over her throat and face.

“Did you …?”

She broke off, embarrassed beyond words. Guy Denver stopped looking grim and for the first time smiled. He patted her hand.

“That’s all right,” he said, “don’t think anything about it. I had to put you to bed. You were in a state of shock, and you needed warmth and looking after. I had to see to your head, too. You see I’m a doctor of sorts—women mean nothing to me.”

And to himself he added:

“Nothing … after what Frances did to me—and they’ll mean nothing to me, ever again!”

Celia Hammond lay motionless, staring at the man. It was an extraordinary thing to find herself alone in a deserted house with a stranger. And not a little frightening. Except that it made it better to know that he was a doctor. He seemed to have done a lot for her. He was telling her that he had made quite a neat job of her wound, in spite of the fact that his instruments were limited. It was lucky, he told her, that he had left a case in his car. But he felt that she ought to see another surgeon quickly, just to make sure that he had done his work well. With any luck, they would drive off tomorrow.

She watched him while he was speaking. With a pipe between his teeth, he stood by the fire at the foot of the bed. Celia, like any other girl, appreciated good looks, and this Dr. Denver, as he called himself, was definitely handsome … in a rugged way. Crisp, brown hair, springing vitally from an intelligent forehead, narrow grey eyes and firm lips and chin. A man with virility in his face, eyes that one could trust.

Celia swallowed hard. She must be able to trust him, or it would be too ghastly … at his mercy, here, with her head-wound, her helplessness.

Now he was questioning her. She told him about herself. How, until a month ago, she had been living quite happily near Lincoln in an old manor-house with her father for whom she had kept house since her mother had died. Humphrey Hammond was a retired solicitor. He had given Celia a first-class education but no training for any specific job. He meant well, but when he had died, suddenly of heart-failure, Celia had been faced with disaster. His investments had gone wrong. He had left nothing behind him but debts. She had had to sell everything, except the lit. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...