1

Frumpy, greasy, chubby Mildred. Zitty, dorky, ugly Mildred. Weak, slow, stupid Mildred.

Those were Mildred’s foremost thoughts on a typical early morning, an entire school day ahead of her. She glared at her reflection in her floor-to-ceiling bathroom mirror. Mirror Mildred stared back at her out of sad, mud-brown eyes, the kind of brown found in swamps and backed-up toilets. The kind of brown people ignore or immediately turn away from should they realize they’ve looked too deeply into them. There she stood, surrounded by cold, expensive seafoam-green marble flooring and semiglossed matching walls. A troubled girl.

A broken girl.

Her day began with her mind racing through all the jabs at her appearance she’d heard throughout the years.Unibrow. Her eyebrows were too close together. She hadn’t even known until the other students at Roanoke High told her so. They were both thick and thin in patches and met on the bridge of her nose—two friendly neighbors not really shaking hands but reaching out. Mouth breather. She hadn’t realized she breathed loudly and through her mouth until her classmates teased her about it. They teased her about her clothes, her hair, her shoes, her backpack, her bad gym skills, her breath—any little thing that Mildred did wrong, they let her know. Often. Once the taunts were spoken out loud, Mildred kept hearing them in her mind as they replayed on a loop—all the ugly judgments, mockery, and cruelty. All the nasty insults she was accustomed to hearing swished through her mind like a vicious tornado, leaving a relentless trail of self-loathing behind. She felt the sharp pain of each hurtful word as it pierced her ears and stung her eyes. Felt her heart break from the cruel jabs. Felt less than human—like some alien creature pretending to be human but not doing a very good job of it at all.

Pictures cluttered the edges of her mirror. She’d taped them there herself with clear tape. These were photos of girls she admired. Girls who weren’t her friends—they’dnever be her friends. Some of them she’d taken from school yearbooks, others she’d lifted from her classmates’ social media, and some were famous girls from magazines. The photos were supposed to be there for motivation—a suggestion she’d read in a magazine—but the photos of beautiful people had the opposite effect on Mildred.

She stared blankly into the mirror, hating it the same way she hated those classmates—which is to say deeply, but with a desperate, nagging need to be accepted by them. For nine years, since the second grade, she’d been the outsider, the unaccepted. With the rest of junior year and senior year to go, she’d give anything for that to change. She wanted the mirror to show her someone she would be proud to be. Someone like Michelle “Chelle”

Martin, the pretty girl at school, or even Selena Gomez, who always smiled with a confidence that Mildred wished she had.

But no matter how much Mildred wished, Mirror Mildred remained that girl everybody hated, even though she couldn’t exactly pinpoint why. She had never hurt them, but hurting her seemed to be their favorite hobby. Mildred hadn’t teased Chelle when she’d gotten a bad haircut in sixth grade. Mildred hadn’t made fun of Chelle’s best friend, Yvette, when she was caught stuffing her bra in seventh grade. Mildred didn’t lash out at any of them when they said horrible things to her. She felt angry at herself instead for not finding the courage to stand up to them, for feeling that somehow—deep down—it was all her fault. When she got so frustrated that she cried, it made them laugh harder.

Every little thing they teased her about stuck to her as if she was the world’s biggest insult magnet.

Raggedy Ann. Her dull, dark hair hung thin and stringy down to her round shoulders. Lifeless as yarn. She’d washed it the day before but it was already oily. Crater face. Her pockmarked cheeks poked out like those of a puffer fish, giving her eyes a slightly squinty look. She used various creams for her skin but nothing seemed to work. Piggy. Her round belly stretched her shirt and spilled over her pajama pants. If only she had more willpower, she told herself. Dieting had never been easy for her.

She knew if they had never told her most of these things she wouldn’t see them in herself. Her hair would just be hair. Her skin would just be skin. She knew that she was bigger than most girls—she had been struggling with that issue since childhood.

The other students at Roanoke High seemed to have so much more of a problem with her faults than she’d ever had. With their constant insults, she hyperfocused on their opinions about her.

All she could see in the mirror was the person they’d coaxed her into believing she was.

She decided there wasn’t a single thing about herself that she liked. Not one.

She looked down at her silver bathroom scale. The digital numbers glowed back at her accusingly. Last week, the scale showed two fewer pounds, but then she ate the chocolate pie. And the cupcakes. She’d worked out extra those days. She’d worked out with her mother’s old exercise videos every day this week—a task that she found extremely tiring and lame. All that work made her so hungry. There was only so much jumping around and sweating a person could take, yet she did her best. Still no improvement.

All her efforts had been useless. Tears welled up in her murky brown eyes and slid down her pink cheeks. They fellplop onto her unicorns-and-rainbows pajama top, leaving a wet circle that grew on the fabric, getting bigger and bigger—just like her.

She stepped off the scale and kicked it across the room.

It banged into the marble bathtub, then stayed still. Her toes throbbed.

“Stupid scale,” she said, as if it were personally insulting her the way everyone did at school.

School or hell: it was all the same to her. She would be late if she didn’t get a move-on. Mildred wondered why she even bothered to go to school sometimes. The classes were hard. The teachers didn’t notice her. She had no friends. Everyone hated her. She was too quiet, too weird, too dumb—and, as if that wasn’t enough, there was also the way she looked. Everything about her repelled others. The ones she didn’t repel only wanted to tease her. She wouldn’t even bother going to school except she knew it would be worse for her at home if she didn’t go. Even on days when her parents were away on some work-related trip—which was often—they could still call with their lectures and their threats.

“If you don’t want to go to school,” her father would say,

“maybe you’d prefer to get a job and get your own home.”

“School is the most important part of your early life,” her mother would say. “You’ll never find success without it.”

Easy for them to say, Mildred thought. They aren’t me.

Her mother—Barbara, a slim woman who’d inherited the silky, dark hair of her great-grandmother from Japan—was a marine biologist. Mildred’s father—Ben, a serious man who grew up in Texas—was an ecologist. Science was their life. Her habit of zoning out when they talked work prevented Mildred from knowing exactly what they did at their jobs, but she did know they loved them. Their jobs had brought them together: they had met while studying polar bears in the Arctic.

I just want you to find an interest in science, Mildred,Barbara often said. It’s something that’s essential in life. Something solid.

Scientists are important.

Her parents just didn’t understand. Mildred wasn’t an important kind of person. Science was easy for them. Life was easy for them. They were smart, athletic, and attractive—everything she was not. People actually liked them. Sometimes, she suspected that she’d been adopted. They couldn’t possibly share genetics.

How could two gifted people like them have a loser daughter like me? she wondered.

Sometimes she hated them, because she’d convinced herself that her misfortune had to be their fault somehow. They hadn’t donated to enough charities or helped enough old ladies cross the street. Maybe they’d refused to sacrifice a virgin to a volcano god.

Mildred didn’t know how they’d failed, but they must have done something wrong.

Today, her parents were both gracing the kitchen with their cheerful presence. Barbara stood at the stove, a white apron protecting her ironed blouse and khaki slacks. Pops and sizzles came from the pan—bacon and eggs by the smell of it. Ben sat at the head of the table, browsing the newspapers on his tablet.

He wore an outfit similar to Barbara’s: a white top with buttons and tan khakis, minus the apron. They both liked to dress in plain, solid colors, and everything they ever wore looked new.

They greeted Mildred with smiles as she shuffled into the room wearing a faded purple sweater and old jeans that looked as if they’d been through a few hundred wringers. Mildred didn’t like to smile—she hated her crooked teeth. She tried to focus on the floor tiles, counting the small gray flecks scattered on the white background as she pulled out a chair at the table and parked herself in it. Her father was to her right.

Barbara’s smile faded.

“Are your clothes all dirty, dear?” she asked as she took in Mildred’s outfit. “Has Naomi been skipping on your laundry?”

“No, Mom,” Mildred said. “Naomi does a good job. I just like these clothes. They’re comfy.”

“Comfortable, ” Barbara corrected. “The word you’re looking for is comfortable. That reminds me, Millie, did you hear about Richard?” Richard was the son of Barbara’s best friend from college. “He got accepted to Yale.”

Mildred couldn’t see any connection between beingcomfortable and Richard going to Yale at all.

“You told me last night,” Mildred said, slightly annoyed.

“You know, you can still get into a good college if you just apply yourself,” her dad said, looking up from his tablet long enough to give her a quick, stern look. “You don’t want to end up like Tyler Vaughn, do you?”

The Vaughns were their neighbors, and Tyler was their son.

He was two years older than Mildred, and just as bad as the others who teased her, even though he was on her parents’ payroll as their lawn boy. Every time he passed her he had a name for her that wasn’t on her birth certificate.Lardass. Tubby. Weirdo. Dingbat.

“He had to settle for community college,” Barbara said, and she cringed as if that was the worst thing a person should have to do.

“Could you imagine?”

Mildred watched the wave of disgust wash over her father. He put the tablet aside as Barbara set a plate before him.

“One thing is for sure,” he said. “No daughter of mine is going to be a flunky.”

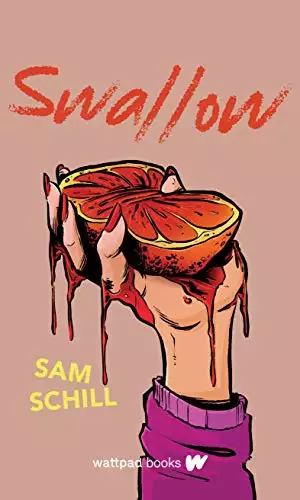

Mildred had known something like this was coming. She’d been through these talks before with her father. If she said anything in her own defense, he would bring up her grades. He’d bring up her extracurriculars. Her overall “lack of effort,” as he saw it. She grumbled, ignoring the comment, and stared sulkily at the plate her mother placed in front of her. A small portion of eggs—all whites—a slice of bread—wheat—and a grapefruit filled only the center part of the dish. No regular eggs or bacon, like on her father’s plate. No regular toast, the way she preferred, like on her mother’s. Just a bit of egg whites, wheat bread, and one silly grapefruit. In fact, Mildred would bet it was the smallest grapefruit in the bunch. It wasn’t a meal. Not even a proper snack, really. How was that supposed to hold her over until lunch hour?

“Can I have some regular eggs, toast, and bacon?” she asked.

Barbara clicked her tongue on the roof of her mouth in her disapproving way. “Millie, honey, you’ve got to stick to a strict diet if you ever hope to drop the weight. You’d be so pretty if you’d just—”

Mildred rolled her eyes thinking, Here she goes again. “I just want some normal eggs, Mom, not a chocolate-filled doughnut.”

Her mother pursed her lips while she considered the request.

“I don’t think you should. You have the protein you need in those egg whites, and—”

“Thanks, Mom,” Mildred said hatefully. “But I don’t have time for breakfast this morning. I’m going to be late.” Her chair’s legs screeeeched heavily across the tile floor as she scooted back from the table. She could see she wouldn’t get a decent breakfast here.

Not under the watchful eye of Miss Perfect.

“Okay, honey,” her mom called after her as Mildred slipped on her shoes and headed for the garage door off the side of the living room. “Do your best!”

Instead of walking to school, like she’d vowed to do every day since last week, Mildred got on her light-pink moped. She thought she’d save some time exercising by walking, but that was before she realized how long getting results took. There didn’t seem to be much reason to waste time and energy walking if she was still going to be overweight at the end of the day, she decided.

She strapped on her helmet, started the motor, and sped out of the driveway. On her way to Roanoke High School, Mildred took a short detour to Debbie’s Doughnuts.

The little bakery was just opening for the day. She walked up to the brightly lit display counter and let her eyes roam over the delectable sweets inside. Debbie was talented and took pride in her displays. She baked fluffy doughnuts and coated the tops with frosting in sports team colors, flowers, hearts, emojis, and she also took requests. Round cinnamon buns glistened, stacked neatly in a pyramid. Beside them were cupcakes covered with edible glitter and rainbow icing, cookie sandwiches, and then Mildred’s favorite: chocolate-filled doughnuts. Everything looked neat and smelled fresh enough to taste in the air. From experience, she knew they would taste as delicious as they looked and smelled.

There wasn’t a bakery around that could beat Debbie’s Doughnuts.

Debbie, a cheerful woman with bright-yellow hair, was behind the counter kneading dough. When she saw Mildred, she stopped and gave the girl her full attention. “What can I get’cha today, Millie?”

Mildred ordered a chocolate-filled doughnut. It was heavenly, as always. Soft, sweet dough and fluffy chocolate filling that caressed her taste buds with bursting flavor. She chased it with rich chocolate milk. It was bad for her, she knew that, but the taste made her feel less sad inside. It made her feel like life was worth living to enjoy the flavors. As far as she was concerned, every single bite of her doughnut was worth the extra pounds and the trouble of being a little late. It was so tasty, she bought another one for the road.

2

The unrelenting screech of Patsy Porter’s alarm clock flooded her ears and reverberated in her head, snapping her out of a deep sleep. Instinctively, she stretched toward the sound, but found a barrier holding her back from its shut-off button. An end to the racket was hidden somewhere beneath a strange cover of fabric.

“What the—”

Leaving things on top of her alarm clock was something Patsy would never do. It was, in fact, something she hated very much.

She worked through her sleep hangover and tried to think clearly.

Where did it come from? Her bedroom was so small and filled with so much that everything had a specific place to be in her room. If she couldn’t file it away, it didn’t belong. This thing had been left in the one place where she would be sure to notice it as soon as she woke up, which meant that someone had been in her room while she slept—a concept that gave her a twinge of the creeps. Not only because she was out cold and vulnerable but also because their presence threatened her organized personal space.

There was only one person she knew who had an annoying habit of invading her personal space.

Mom.

Patsy reached beneath the barrier to stop the blaring noise, then went back to the fabric, allowing herself a moment to enjoy its smooth silkiness. It was as soft as powder in her hands—expensive material for sure. She unfolded it as she stood up. A cashmere and silk Burberry scarf spread open and her jaw dropped as she thought about the value. Those scarves didn’t come cheap; they cost big bucks. There was no way anyone in the Porter house had that much money to spend on an accessory. Of course, she knew instantly that nobody had spent anything on it. Coming from Kathy Porter, it was most likely stolen.

Patsy did a once-over to check if anything needed tidying after the invasion. Nothing else in her room appeared to have been touched. Not her neat makeup vanity. Not her dresser or her closet—contents sorted neatly by size and type—and not her school things lying on the small chair by her door. Not the special little wooden box hidden behind the old photo on her top shelf.

Everything, aside from the new scarf, was exactly how Patsy had left it when she had shut her eyes the night before. She clutched the delicate fabric in her hand, careful not to scrunch it.

“Mom!” Patsy shouted as she left her room.

She found her mother lying on the living room couch, wrapped tightly in a blanket. There was only one bedroom in their apartment, so the couch doubled as her mom’s bed. Her thick strawberry-blond mane covered most of her finely lined, freckled face—a face that looked a lot like Patsy probably would in twenty years.

“Mom. Where did you get this?” Patsy demanded, although she already had a strong idea.

Kathy snorted as she opened her eyes. “Gift,” she said. “Happy birthday.”

“It’s not my birthday, Mom. My birthday was in April.”

“I know.” Kathy sighed and sat up. “So then happy whatever.

Can’t you just be grateful?”

“I asked you to not bring me stuff from your employers. What happens when someone notices it missing and sees me wearing it somewhere? What then?”

“Relax. Mrs. Harding gave it to me.”

“Did she really?” Patsy asked suspiciously. It still smelled of whatever perfume Mrs. Harding had doused it with. Something exotic, most likely. She had several bottles from Paris, even without counting the two that her mother’s sticky fingers had slipped away undetected. Patsy studied her mother, willing a truthful answer she knew she would probably not get.

“Yep,” said Kathy, who didn’t seem to care she was being scrutinized. She yawned and finger combed her untamable hair away from her eyes. “I’m going to go shower. Make me an omelet?”

Patsy deflated. “Sure,” she said, knowing further scolding would do no good. Her mother was set in her ways. And how had Patsy become the mother figure instead of the other way around anyway?

As she prepared ingredients for an omelet breakfast for two, Patsy couldn’t help but stare at the back of the dining chair, where she’d draped the scarf, as if it were sending her messages from across the room that distracted her from the task at hand. Look at me!

There weren’t many eggs, but four was enough. Two each. The scarf was so pretty. Eggs sizzled in the pan and she rinsed the shells out so they wouldn’t smell in the trash can. The way the fabric had felt: delicately soft, like a bunny. There were no fresh veggies to add to the omelet, as she would have liked—they just hadn’t had enough money over the past few weeks to get fresh food. She rummaged in the cabinet and didn’t find much. Some canned spinach would work. She added it to the eggs.

That scarf was luxurious. Something as upscale as that could really give her an upper hand at school. She wasn’t envied there, but she wasn’t invisible either. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved