- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

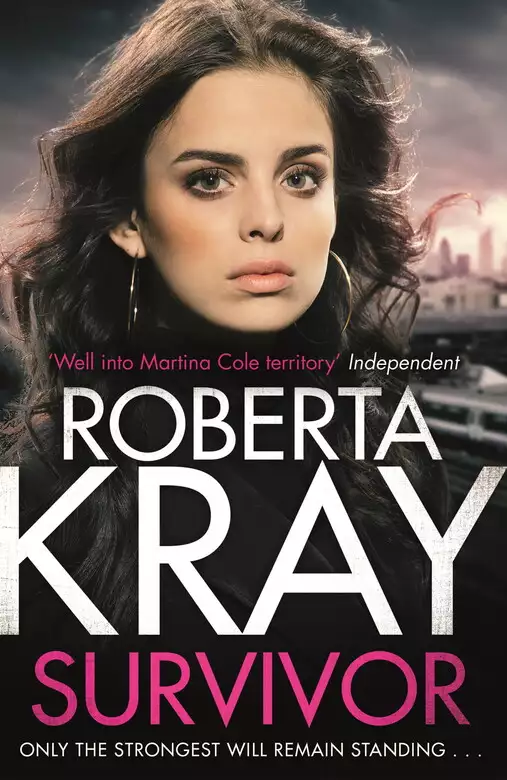

'Well into Martina Cole territory' Independent

THE ADDICTIVE NEW THRILLER: NO ONE KNOWS CRIME LIKE KRAY

Lolly has always known her mum was different. Sometimes Angela Bruce was ill in a quiet sort of way, but other times she roamed the Mansfield estate shouting about whatever had wormed its way into her head that day. Either way, Lolly was on her own so she learned how to look after herself pretty quickly.

Mal Fury has never got over the disappearance of his daughter all those years ago, but there's still hope because the police never found Kay's body. So when his private investigator turns up a lead that connects Kay to Lolly, Mal needs to find out more. But in doing so, he's delving into a decades-old mystery that could throw Lolly's entire world into chaos and she'll need every ounce of her survival instinct if she's to make it out the other side . . .

Release date: November 2, 2017

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Survivor

Roberta Kray

He looked at his watch. There was still some time. Slowly he made his way down to the water’s edge. The lake was calm, gunmetal grey and fringed with bulrushes. A fine, hazy mist hung over the surface but he could just make out the house across the other side, a substantial three-storey white building. His upper lip curled a little; other people’s good fortune always filled him with resentment.

Glancing both ways along the path that circled the lake, he kept his eyes peeled for unwanted company. On all the occasions he’d been here before, he’d only ever seen one other person apart from the nanny, and that was the handyman walking the family’s black retriever. The nanny was a slight girl who wouldn’t put up much of a fight. No problem there. He could take her with one arm tied behind his back. What he didn’t need was an interfering have-a-go hero or, come to that, some fucker of a dog trying to chew off his balls.

He stood for a while before retreating back into the shelter of the trees. Crouching down, he lit a fag, impatient now for it to begin. The waiting around was the hardest part. He went over the plan in his head, step by step, and automatically checked his pockets to make sure the coils of twine were still there.

The minutes dragged by and the chill autumnal air began to seep into his bones. He needed a drink, a good strong shot of whisky. His tongue slid across his dry lips. He finished the cigarette, dug a small hole in the ground with the heel of his boot, dropped in the butt and covered it with soil and leaves. He stretched out one leg and then the other, and thought about what he’d do when it was all over. Go abroad, perhaps, and get some sun. He was tired of the cold, grey British weather, tired of everything about Britain.

And what about Hazel? If the truth were told he was sick of her as well. The things that had initially attracted him, her innocence and wide-eyed adulation, had long since lost their appeal. These days she just got on his nerves. Still, she had her uses. He’d need her over the next week or so, and after that she was history. He didn’t have to worry about her grassing him up; she was in it up to her neck and if she went to the law she’d be sealing her own fate too.

It was a further five minutes before he heard the sound of the pram’s wheels. Instantly he was alert, the adrenalin starting to flow. He pulled the scarf up over his nose and mouth. Then he got to his feet and began quietly to move down towards the lake. The girl came into view. She was dressed in a drab brown coat and her lips were moving slightly; she was talking to the baby or herself or maybe mouthing the words to a song.

He crept close to the path and waited for her to pass by before leaping from the bushes and pouncing from behind. She stiffened with fear and panic as his arm snaked around her neck and his gloved palm clamped hard against her mouth. With his body pressed against hers, he knew he had absolute power over her. It was a gratifying, almost sexual feeling – but he wasn’t here for that.

‘Don’t try anything, love, or I’ll snap your fuckin’ neck in half!’

Paralysed with fright, she didn’t dare move. He had her. Now all he had to do was make sure she stayed bound and hidden while he grabbed the baby and got the hell out of there. But then, as he tried to drag her towards the undergrowth, something unexpected happened. As if waking from a nightmare, she suddenly kicked out, catching him on the shin. He gasped in surprise, loosened his grip, and she twisted away from him. In the ensuing struggle, they grappled with each other, a messy desperate battle. She was small but she fought like a wildcat: bug-eyed, terrified, hysterical. As he tried to subdue her, he stumbled and barged into the pram.

There was a moment when time slowed and stretched, when seconds became interminable, when the wheels continued to turn and the pram lurched off the path, travelling down the bank towards the lake. There was a holding of breath, a terrible stillness in the air. He knew he had a choice: leave the girl and grab the baby or… But he hesitated too long and the pram slipped into the water with a soft splash, tilted and turned over.

The girl let out a cry. ‘Kay!’ And then she started to scream.

He snapped into action. He had to silence her before she alerted the whole bloody world to what was going on. As he yanked her towards the lake, he covered her mouth with his hand. ‘Shut up! Shut up, you stupid bitch!’ And then, because he couldn’t think what else to do, he shoved her hard and sent her flying into the water. It had the desired effect. The shock of the cold rendered her speechless and as she scrabbled around, arms flailing, he waded in to retrieve the child.

The pram was on its side, half submerged. He snatched up the soaking wet bundle but couldn’t tell if the baby was alive or not. It had only been a short while, not long enough to drown, surely, but she was an odd colour and her eyes were closed. He started making his way towards the bank, but suddenly the girl was on him again, tugging at his coat, clawing at his arms, trying to snatch the kid off him.

‘Give her to me!’

He pushed her away with his free hand but she kept coming back. By now the scarf had slipped off and she could see him clearly. Fuck it! Damn! She wouldn’t have a problem picking him out in a line-up. And suddenly he couldn’t think straight. All kinds of shit was running through his head, including the prospect of a long stretch. He had a sudden flash forward to standing in the dock while a judge sent him down. Ten years? Twenty? Child abduction came with a heavy price. Rage and panic flowed through his body. No, he wasn’t having it. He wasn’t going to jail. He couldn’t.

And meanwhile the stupid bitch was still clawing at him, still yelling, her cries echoing around the lake. Why wouldn’t she just shut the fuck up? What he did next was impulsive, instinctive, a matter of self-preservation. He put his hand on the top of her head, grabbed her hair, pushed her under the water and leaned on her with all his weight. He just wanted her to be quiet. He counted off the seconds: one two, three, four, five. He should have let go but he didn’t. She struggled for a while, a futile thrashing of arms and legs – bubbles rose from her mouth to the surface – and then she went limp. He stared down through the grey water, knowing what he’d done but not wanting to acknowledge it.

Finally, he disentangled his fingers from her hair. She didn’t move. And now what was done couldn’t be undone. How had it happened? It shouldn’t have happened. It was her fault, he told himself. If only she’d left well alone…

Quickly, with the baby in his arms, he scrambled out of the water and on to the bank. The kid wasn’t crying, wasn’t doing anything. The blanket was soaked through. Maybe the shock of the cold water had been too much. He didn’t want to look too closely. He just wanted to get away. As he glanced back over his shoulder he saw the girl floating face down in the lake. And now he couldn’t breathe properly. He felt cold, shivery, sick to the stomach. Shit, it had all gone wrong. It had all gone horribly wrong.

By the age of thirteen, Lolly knew her mum was different. Unfortunately everyone on the Mansfield estate knew it too. Sometimes Angela Bruce was ill in a quiet sort of way, indoors with her face turned to the wall, but other times she roamed the walkways of the three tall towers shouting about God and sin, the Elgin Marbles, snakes, spiders, MI5 or whatever else had wormed its way into her head that day.

The flat, on the fourteenth floor of Haslow House, was cramped and damp. Often there was no electricity and no coins to feed the empty meter. Lolly, who was small and skinny and always hungry, had learned to scavenge. She would root through other people’s bins for leftovers, or beg from the market stalls when they were packing up at the end of the day. Her clothes were old and ragged, cast-offs from the charity shops or from neighbours who felt sorry for her.

Today the sky was a clear solid blue. Summer was Lolly’s favourite time of year, mainly because the days were longer and she didn’t have to think about keeping warm. There were also six glorious weeks without school. She was glad to escape from the taunts of her classmates, the name-calling, the hair pulling, the relentless reminders that she was not one of them; she was odd, an outsider, an outcast. Sometimes she bunked off but she knew better than to do it too often. With frequent truancy came a visit from the Social, and that always meant trouble. Those busybodies were just looking for an excuse to take her away and dump her in a ‘home’.

Lolly feared being taken away more than anything else. Well, no, perhaps not anything else. What she feared more was that one day her mum would leave the flat and never come back. This was why she felt uneasy as she gazed into the bedroom. It was seven o’clock in the morning and already the bed was empty. Perhaps it hadn’t even been slept in. She stared at the rumpled blankets but was unable to remember what they’d looked like yesterday.

Last night her mum had been in one of her jumpy, anxious moods, unable to sit still, pacing back and forth across the living room. Every few minutes she’d stop the pacing and go to the window to stare down at the grim wasteland of the estate. Raising her hand to her mouth, she chewed on her bitten-down fingernails.

‘He’s been following me, Lolly. Why won’t he leave me alone?’

‘Who’s been following you?’

‘He has. You mustn’t talk to him. You mustn’t tell him anything. Promise me.’

‘I won’t. I swear.’ Lolly had looked out of the window too, but the only people she could see, apart from a few stragglers, was a gang of lads gathered by the main gate. This happened every evening at dusk. Like a pack of wolves, they came together to hunt down anyone stupid enough to be walking the streets of Kellston alone.

‘We’ve got to be careful. He could be on to us.’

And Lolly had nodded because she’d learnt through the years that agreeing was the only way to keep her mum calm.

‘I think he may be next door. He’s trying to listen. We have to stay very quiet.’

‘Why is he following you, Mum?’

‘You know why,’ she whispered. ‘We mustn’t ever talk about it, not when… there are bugs everywhere. Spies. They’re keeping tabs on us. Can you hear that?’

Lolly had listened but all she could hear was the soft anxious sound of her mother’s breathing. ‘What?’

A knowing, tight-lipped smile was the only response.

Lolly was still turning this over in her head as she walked to the bed and placed a palm on the grubby sheet. There was no warmth, no indication that anyone had been lying there recently. That wasn’t good. She could have been gone for hours. Once, a year or so ago, she’d disappeared for two days and had eventually been found curled up, foetus-like, in the dark space at the bottom of the stairwell.

Lolly went through to the living room, opened the doors that led out to a narrow balcony and leaned over the rail. She scanned the estate, searching for the slim, slight figure of her mother, for the pale blue jacket and the familiar stream of long black hair. No sign. There was hardly anyone about. She listened carefully but heard only the distant sound of traffic from the high street. An uneasy feeling was starting to stir inside her.

It didn’t help that she was starving hungry. She’d gone to bed on an empty stomach and now she was desperate for something to eat. After closing the balcony doors she went to the kitchen and looked in the fridge. It had no light and, despite being empty, a bad smell wafted into her nostrils. She slammed shut the door and went to check the cupboards. She wasn’t sure why she was bothering – there’d been nothing in them last night – but she lived in hope of miracles.

On this occasion, like most of the others, her hopes were immediately dashed. Her face fell as she crouched down and gazed at the empty shelves. Not even a few stray cornflakes or a tin of beans. If she wanted breakfast, she’d have to go out and hunt for it.

Lolly put on her thin cotton jacket with the deep pockets (she never knew what she might find), made sure she had the front door key, and left the flat. In the shared hallway she pressed all the lift buttons and waited… and waited. There was no indication that anything was happening. They were probably jammed again, or some kids were messing about on the ground floor, keeping all the doors open.

‘Come on,’ she said impatiently, jabbing at the buttons. ‘Come on, come on.’

The estate had only been built about fifteen years ago but already it was starting to fall apart. The once-white concrete walls had turned grey and there were long ominous cracks running up the outside, some of them big enough to slide a finger into. The metal railings were rusting. Damp crept through the building and into the flats, black mould gathering on ceilings like a horrible disease. The whole estate had an air of despondency about it as if the residents, many of them stranded up in the sky, thought of the place more as a high-rise prison than a home.

Lolly couldn’t clearly remember living anywhere else, although she knew she had. They’d moved here years ago but she wasn’t sure where from. Her mum was always vague when asked, saying things like ‘Oh, here and there,’ or, if she was in one of her more suspicious moods, ‘Who have you been talking to? Has someone been asking questions? You mustn’t tell anyone anything, Lolly.’ As if she had anything to tell. Her memories were vague and dreamlike, odd wisps that floated through her mind.

After a few minutes, Lolly gave up on the lift and decided to take the stairs instead. Fourteen floors was a long way to walk but it wasn’t so bad when you were going down. It was the going up that made your legs feel like lead and pulled the air out of your lungs. She sang to herself as she made the descent: ‘Knock Three Times’ by Dawn.

By now the estate was starting to wake up. She could hear the muffled sound of radios, of voices, of toilets being flushed. The day was going to be a hot one and most people had the upper part of their windows open, the part that was too small for any thieving bastards to climb through. Crime was rife on the Mansfield and anything not nailed down disappeared in five minutes flat. The cops were always around, knocking on doors.

On reaching the ground the first thing Lolly did was to check the base of the stairwell to make sure her mother wasn’t there. She approached it with caution, afraid of what she might find. In the event there was nothing scarier than a pile of litter, a load of fag ends and some empty bottles. She stared into it for a moment and then quickly withdrew. It was dark and nasty and stank of pee.

Lolly wasn’t alone as she crossed the estate and headed for the main exit. There were people emerging from all three blocks; men and women on their way to work. Most had the same miserable expression on their faces as if the day, even though it had only just begun, was already a disappointment to them.

She set off for the high street. Her favourite spot for discarded food – apart from the market – was round the back of the Spar. Now was a good time to go before the staff came in to open up. As she walked she kept her eyes peeled for her mum. Lolly was always worried about her. Was she sleeping? Was she eating? Was she getting sick again? It was as though their roles had been reversed and she was the parent. There had been a time – she was certain of it – when things had been different, but now she just accepted the situation as normal. Other mothers didn’t do the things hers did, but that didn’t matter. Her mum was the only one she wanted.

Lolly’s gaze made a wide sweep as she left Mansfield Road and turned left into the high street. She looked up and down the length of it – no sign of her mother – before she started checking the pavement and the gutters. Sometimes there were pennies to be found, loose change that had slipped from someone’s pocket. Once she had even found a shilling. That kind of luck didn’t come too often but it paid to be vigilant. It was surprising how careless people could be.

Halfway down the high street she passed the pawnshop, still with its steel shutters down. It did a brisk trade during opening hours with customers exchanging their valuables – and everything else they could lay their hands on – for ready cash. It was run by Brenda Cecil, a woman who was built like a house and who had clearly never missed a meal in her life. No one messed with Brenda; there were rumours she kept a baseball bat under the counter and wasn’t afraid to use it.

Lolly didn’t like Brenda, or perhaps it was just that she didn’t trust her. Was that the same thing? She was the kind of woman who placed a value on everything from what you were wearing to the furniture in your home. She knew this because Brenda popped round to the flat for a brew from time to time. The woman’s eyes would move slyly round the living room as if she were making mental calculations as to what each item was worth.

Lolly’s mother didn’t have many friends, at least not the sort who stuck by her when she was ill, but Brenda’s friendship never seemed quite real; she was always asking questions, always digging in a roundabout sort of way. There was something false about her. Lolly couldn’t exactly put her finger on it. She couldn’t put it into words. It was just a feeling.

She carried on walking until she came to the narrow alley that led round to the back of the Spar. Here hunger got the better of her and she jogged the last twenty feet until she reached the yard with the old metal bins. One quick glance around to make sure no one was watching and then she dived in. Almost instantly she saw that the pickings were slim. Her mouth twisted with frustration and disappointment. One of the bins was empty and the other only had a few bits of cardboard, a couple of bruised apples and a badly dented tin of corned beef. She grabbed the tin and put it in her pocket. She took the apples too – if she cut the bad bits off, there’d still be some left.

Lolly’s next port of call was the chippie. She went back up the alley, along the high street and checked the bin outside the shop. Reaching down she squeezed the scrunched up wrappings until she found a likely prospect. Pulling it out, she opened up the sheets of newspaper to reveal a handful of chips. Last night’s leftovers, cold and congealed, but she wasn’t fussy. She stuffed them into her mouth, too hungry to care about germs or someone else’s spit.

When she’d finished, she crossed over to the green. It wasn’t really big enough to be called a park. It was about the size of a football pitch, a grassy oblong with trees and bushes and a few seats. Sometimes her mother came here to sit and gaze into space, but today the benches were all empty. She skirted round the mounds of dog poo and headed back to the high street.

At the café, Lolly pressed her nose against the glass and peered in through the window. Through the fug of fag smoke, she could see there were no women inside, only a load of blokes drinking mugs of tea and reading their papers. The smell of frying bacon and eggs floated in the air making her mouth water. The abandoned chips had taken the edge off but she was still hungry. She’d have killed for a hot breakfast.

With nothing else to do, Lolly wandered back to the Mansfield. She wasn’t sure of the exact time now but the traffic was starting to build, the red double-deckers and the cars lining up along the street. She checked the main paths and walkways of the estate, strolling round each of the towers in turn. Once she’d established that her mother was in none of the more obvious places she decided to go home and wait there for a while. There was probably nothing to be concerned about – it wasn’t as if her absence was anything new – but she wouldn’t stop worrying until she saw her again.

It was a relief to find the lifts were working and she took one up to the fourteenth floor, trying not to breathe too deeply. They always stank. Why did blokes pee in lifts? She didn’t get it. Still, it was worth the stench if it meant she didn’t have to climb all those stairs.

‘Mum?’ she called out as she went through the door.

Silence.

Lolly could sense the flat was empty. It had that peculiar stillness, that lonely hollow feeling. Her heart sank. Where was she? With a sigh, she gazed around the living room as if by sheer force of will she could make her appear. It was hard not to imagine the worst, but she tried to push those fears aside. Instead she sat down on the battered sofa, took the tin of corned beef out of her pocket, pulled off the tiny metal key and set about the tricky business of getting it open without slicing off her fingers.

Lolly only had one friend on the estate, one other person she could trust. By midday, when her mother still hadn’t shown up, she walked down to the twelfth floor and knocked on the door. It was a while before he answered. She jumped from one foot to the other while she waited, playing invisible hopscotch on the floor. Finally, he opened up and looked down at her. Jude Rule was tall and gangly with a lock of dark brown hair that fell over his forehead. He was older than her, sixteen, but he didn’t treat her like a little kid.

‘Hey, Lolly. What’s up?’

‘Have you seen my mum?’

‘She gone AWOL again?’

‘Kind of.’

His eyebrows shifted up a notch before he stood aside to let her enter. ‘She’ll be okay. You want to come in for a while?’

Lolly followed him through to the living room. It was as dark as always with the curtains pulled across. A tight white sheet took up a quarter of the wall, and black and white images flickered across the makeshift screen. She stopped and stared. ‘Which one is this?’

‘Dead Reckoning. Bogart and Lizabeth Scott.’

‘Why do you always watch old films?’

‘Because I like them. You want a sandwich?’

‘Yeah, if you’re making. Ta.’

‘Sit down, then. It’ll have to be peanut butter. We’ve got nothing else.’

Lolly sat down on the green corduroy sofa and stared at the screen. She’d seen this film before although she hadn’t remembered its name. It was about Rip and Coral. Rip – Humphrey Bogart – was the good guy, and Coral was trouble. The women in most of the films Jude liked were trouble. They were wild and independent and beautiful, but they didn’t behave in the way women were supposed to. And for that they always got their just deserts. Coral was going to end up dead just like she had last time.

Lolly shifted her gaze to the open door of the kitchen. Jude was wearing grey shorts and a dark blue T-shirt. She watched as he buttered the bread, watched the sweep of the knife and his long slender fingers. She knew he was odd but that didn’t bother her. She was used to odd. Jude was a film freak and spent all his free time either going to the cinema or watching at home. He didn’t seem to like the daylight much.

Lolly knew she could always get food at Jude’s, but only if his father wasn’t around. His dad, a tall taciturn man, didn’t like other people being in the flat. She wasn’t allowed in if he was at home. A projectionist at a West End cinema, he worked shifts and was usually out in the afternoons and early evenings.

She shifted her gaze again to the shelves to the right of the screen, all filled with film reels in boxes. In the flickering light, she could see some of the titles scrawled on the sides: Sunset Boulevard, Double Indemnity, The Lady from Shanghai. There must have been hundreds of them. She started to count but lost interest at twenty-four when Jude came in with the food.

‘Here you go.’

Lolly made an effort not to snatch the plate from him. Although she’d eaten half the corned beef, that was ages ago and she was hungry again. Jude’s sandwiches were like doorsteps, big and bulky, the bread bought from the bakers on the high street. She knew that was where Mr Rule got it because she’d seen him in there. He never bought the sliced stuff from the Spar.

‘Where have you looked?’ Jude asked, sitting down at the other end of the sofa. ‘For your mum, I mean.’

‘All over.’ Lolly talked with her mouth full, deciding this wasn’t rude if the room was dark and no one could see her doing it. ‘All round here and on the high street. I went to the green too.’

‘She acting funny again?’

Lolly shrugged. ‘She thought she was being followed yesterday. I don’t know if she slept at the flat. She wasn’t there when I got up this morning.’

Jude made a tutting sound with his tongue. ‘She shouldn’t leave you on your own. It’s not right, Lol.’

‘She can’t help it if she’s scared.’ Lolly knew that Jude had strong opinions about mothers who didn’t look after their kids. His own mum had done a bunk years ago. He said he didn’t care but she knew he did. Whenever he talked about her his face got all fierce and red and he’d chew down on his lower lip as if to stop it from doing things he didn’t want it to do.

‘What’s she scared of?’

‘All sorts.’

‘Did you check the caff?’

‘Yeah.’

Jude stretched out his long pale legs and gazed at the screen for a while. Rip and Coral were exchanging meaningful looks. Then, without turning, he asked, ‘Why did she call you that?’

‘What?’

‘Your name. Why did she pick that name?’

‘Lolly?’

‘No, your real one. Lolita.’ Then he split it up, drew it out and said again, ‘Lol-it-a.’

She felt instantly defensive as though he might be laughing at her. ‘What’s wrong with it?’

Jude pushed some sandwich into his mouth and chewed. ‘Humbert Humbert.’

‘Huh?’

‘You ever heard of a fella called Nabokov?’

Lolly shook her head. ‘Who’s that?’

‘He’s Russian, a writer. He wrote a book called Lolita. It’s about a middle-aged bloke called Humbert Humbert who falls madly in love with his landlady’s daughter. She’s actually called Dolores, but his secret name for her is Lolita. And she’s only twelve.’

‘He’s weird, then.’

‘Yeah, he’s really weird. He even marries the landlady so he can hang about with her. Creepy, yeah? They made a film out of it too. James Mason played the bloke. But they changed the girl’s age so she was fourteen instead.’

‘What kind of a name is Humbert Humbert?’

‘One you remember,’ he said, grinning. ‘Like Lolita.’

Lolly put the empty plate on the coffee table and wiped the crumbs from her mouth. She slipped her feet out of her shoes, pulled up her knees and wrapped her arms around her legs. She liked making herself small, sinking down into the darkness. ‘My mum doesn’t have many books.’ She didn’t tell him there was only one in the flat, a well-thumbed collection of British fairy tales. Once upon a time her mother had read to her, stories called ‘Mr and Mrs Vinegar’, ‘The Secret Room’, or ‘The Changeling’, but now she was too old for make-believe.

‘Humbert reckoned Lolita was a nymphet.’

Lolly stared hard at Bogart while she wondered what a nymphet was. There were sprites and nymphs in the fairy stories but she had the feeling this wasn’t what he meant and she didn’t want him to think she was stupid. She rolled the word over her tongue – nymphet, nymphet – while she tried to figure it out.

He saw the expression on her face and laughed. ‘Nymphets are birds like Amy Wiltshire.’

Lolly knew who Amy was, one of the popular, pretty girls who all the boys fancied but pretended not to. Although she was the same age as Jude and in the same class at school, she looked older. She had big breasts, a slim waist and green eyes like a cat’s. Her hair was long and blonde and she was always swishing it back off her face. ‘Do you like her?’

‘Boys don’t like girls like Amy. They just want them.’

Lolly heard the longing in his voice and felt her stomach shift. She didn’t like the idea of him lusting after Amy Wiltshire – or lusting after anyone come to that. Her crush on him, although always carefully hidden, was a constant source of awkwardness and pain. She squinted at him through the gloom. ‘What’s the difference?’

‘Like when you want something that you know is really bad for you. It looks all nice on the outside but…’ He paused, his eyes narrowing a little. ‘Inside, it’s no good. It’s rotten. Except you don’t always find that out until it’s too late.’

‘Is Amy rotten?’

Jude’s mouth twisted. ‘To the core.’

‘Like Coral.’

‘Yeah, just like Coral.’

Lolly squeezed her legs more tightly and settled her chin on top of her knees. ‘But what makes them bad? I mean, are they born that way or has something awful happened to them? Are they —’

‘What does it matter?’ Jude roughly interrupted. ‘You can’t make excuses for the bitches. They’ve got bad souls and that’s the beginning and end of it.’

Lolly shrank back into the corner of the sofa. She didn’t like it when he spoke like this, when his expression became hard and angry. And who was he actually talking about? Was it Amy or Coral? Maybe even his mother. She pondered on what it felt like to have a bad soul. Like a stomach ache, perhaps, or a nagging toothache that throbbed and throbbed and kept you awake at night. Or maybe it didn’t hurt at all. Maybe you didn’t even know you’d got it.

Jude threw her a glance. ‘What’s wrong? What’s the matter?’

‘Nothing.’

‘So what’s with the face? I’m only saying it like it is. Don’t start going all moody on me.’

‘I’m not.’

‘Yes you are.’

Lolly sighed into her knees. ‘I was just wondering.’

‘Wondering what?’

She took a moment to gather her thoughts. ‘About being bad,’ she said. ‘What if… what if I’m bad too? I could be. I could be a bitch.’

Jude threw back his head and laughed. ‘You?’ he said. ‘Don’t be ridiculous! You’re nothing like that. You’re not that type at all. Jesus, you’ve no worries on that score.’

By which he undoubtedly meant she wasn’t beautiful enough to stir up feelings – be they good or bad – in the pure white souls of boys like Jude Rule. Lolly felt her cheeks burn red and was glad of the cover of darkness. ‘You can’t know that,’ she insisted, sounding more petulant than she intended.

‘Believe me, I do. What are you thinking?’

Lolly shrugged. ‘I don’t see how you can tell how people are going to turn out. You can’t be sure of anything.’

‘Crap,’ he said. ‘There are plenty of things you can be sure of.’

Lolly leaned forward slightly, letting her long, straight brown hair fall across her face like a curtain. She didn’t want him to be able to see her properly. There were tears in her eyes but she didn’t dare brush them away in case he noticed. She knew Jude would never love her the way she loved him. She was small and skinny and plain. Her chest was as flat as a pancake. She didn’t even know how to smoke. Amy Wiltshire could smoke; she smoked with style like Lauren Bacall.

There was a few minutes’ silence between them while the final scenes of Dead Reckoning played out on the screen. Lolly watched without really watching, her mind full of Jude. She flinched a little when he spoke again.

‘What do you fancy next, then? The Big Sleep, Sunset Boulevard?’

Normally Lolly would have leapt at the opportunity to spend a couple more hours with him, but not today. She felt all twisted up inside, winded, as though she’d been punched in the stomach. Quickly she jumped to her feet.

‘I can’t. I’ve got to go.’

Jude didn’t try and persuade her to stay. He didn’t even ask where she was going. He wasn’t bothered whether she was there or not. ‘Okay. See you, then.’

‘See you.’ While the credits slid down the screen, Lolly made her way to the door and let herself out. As she stepped into the outer hallway she could still hear his voice echoing in her mind: Lol-it-a, Lol-it-a. She rubbed at her face with both her palms; her hands felt warm and sticky.

Lolly hit the button for the lift and then, while she waited, walked over to lean on the rail and look down over the estate. It was after one now and the sun was high in the sky. It beat down on the concrete tower, spreading warmth through the stone and the rusting metal of the rail. She breathed in the hot air, feeling its dusty thickness catch in the back of her throat.

As she glanced over to the right her attention was drawn to a crowd gathered outside Carlton House on the patchy square of grass. Something was happening. She leaned out over the rail and shielded her eyes, trying to get a better view. It was probably a bust-up between some of the local lads; they were always knocking seven bells out of each other.

A short ting told her the lift had arrived and she moved back, intending to return to the landing. But just as she was about to look away, the crowd shifted and she was able to catch a fleeting glimpse of what they were all gawping at. Immediately she froze, her blood running cold. Her eyes widened with shock and horror. The hairs stood up on the back of her neck. It couldn’t be… it couldn’t. But there was no mistaking that flash of pale blue, that stream of long dark hair.

The crowd moved again like a door closing, and her view was obscured. But she knew what she’d seen. For a moment Lolly’s legs wouldn’t move. Her feet were stuck to the ground as though they were glued. She felt sick, dizzy, overwhelmed. And then, just as she thought she might faint, the adrenalin kicked in.

Lolly lurched away from the railing and sprinted back inside. She hammered on the door with her fists. ‘Jude! Jude! Jude!’

Lolly launched herself down the stone steps as though the devil was on her heels. She ran with abandon, with desperation. No, it couldn’t be her. It couldn’t. Panic swept through her mind, drowning out every other thought. A sharp screaming pain was cutting through her head. As she descended the stairwell, the floor numbers flashed before her eyes: eleven, ten, nine, eight… Her chest was heaving, her heart wildly thumping.

Behind her she could hear Jude’s pounding footsteps and the sound of his heavy gasping breath.

‘Lolly!’ he kept calling out.

She didn’t stop. She couldn’t.

By the time she was approaching the bottom, Lolly’s fear had grown to monstrous proportions. Like a fire-spitting dragon, it threatened to engulf her completely, to incinerate the very foundation of her life. One single word was burnt into her consciousness. No. She said it over and over, a mantra to keep the badness at bay. Not far to go now. She jumped the last few steps and hit the ground running. As she was pushing through the crowd, Jude finally caught up with her. He grabbed hold of her elbow and brought her to a standstill.

‘You can’t,’ he insisted. ‘You mustn’t.’

But she had to see. She had to know. She had to be sure.

‘Don’t do it, Lolly.’

He was taller then her, taller than most of the other people. He could see over their heads to what was lying on the ground. She could see the look on his face, an expression halfway between horror and disgust.

Lolly struggled free of his grasp and pressed on forward. Nothing was going to stop her. No one. ‘Let me through,’ she demanded, lashing out with her arms. In the distance there was the sound of a siren, the high whining noise piercing the air. She was suddenly aware of all kinds of odd things, strange disjointed thoughts and memories, as though her life was flashing before her.

She didn’t have time to brace herself, to even begin to prepare for the dreadful vision that awaited her. One second she was pushing through the crowd, the next… Her heart seemed to stop as she saw her mother’s twisted body lying on the grass. The breath flew out of her lungs. A low moan escaped from her throat. No.

Lolly sank to her knees and clutched at the sleeve of the pale blue jacket. Her mother’s grey eyes were half open and glassy, but she was seeing nothing now. A halo of dark red blood ringed her head, seeping into the long dark hair fanned out across the grass. She was lying awkwardly with one arm thrown out and the other trapped beneath her. Her lips, slightly parted, seemed poised to utter some final words, but there was only silence.

Lolly stared. It was her mother and yet it wasn’t. It was what was left of her mother: a broken shell, a shattered life. It didn’t make sense. What had happened to her? Why was she lying here? She couldn’t bear to look at her, couldn’t stop looking. She held on to the jacket sleeve, to the flimsy cotton, as if some comfort could be found in it. She prayed to God that it was all a bad dream. She prayed to wake up.

The sun beat down but Lolly didn’t feel the heat. Shock had wrapped itself around her like an icy blanket. She shivered and her teeth began to chatter. Sounds came from behind, a gasp or two, shuffling noises, muted voices. She could feel the crowd gawping, curious spectators at a gruesome accident. And then one voice rose high enough for her to hear.

‘The poor cow must have thought she could fly.’

It was only at that moment that Lolly realised how her mother h. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...