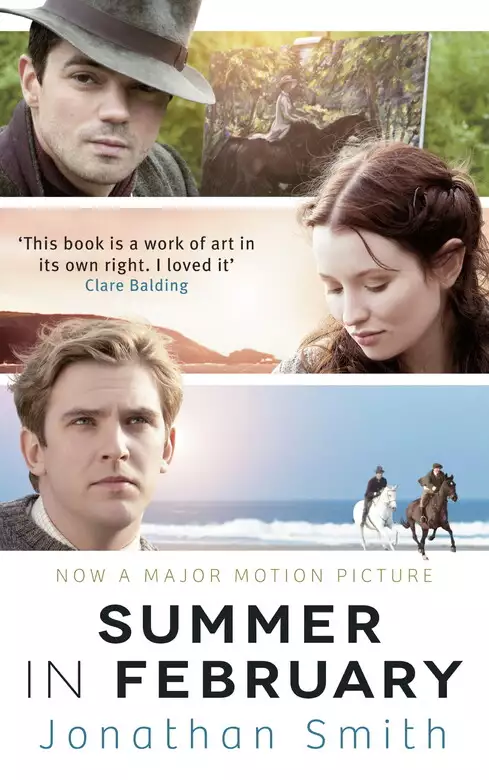

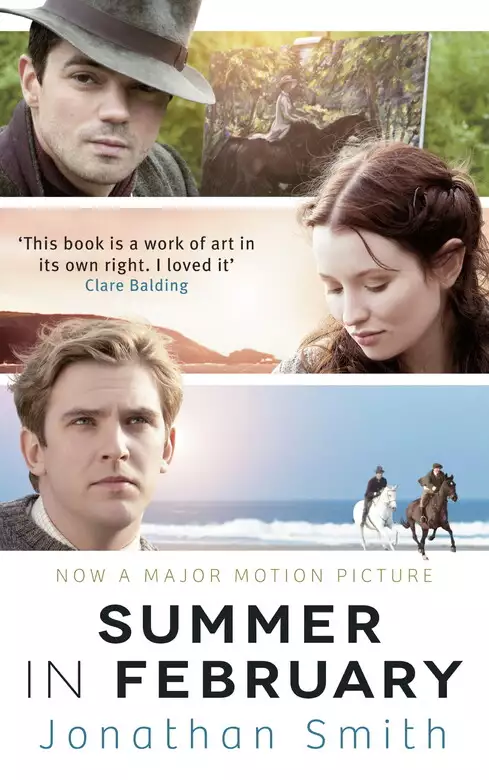

Summer In February

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Sir Alfred Munnings, retiring President of the Royal Academy, chooses the 1949 Annual Banquet to launch a savage attack on Modern Art. The effect of his diatribe is doubly shocking, leaving not only his distinguished audience gasping but also many people tuning in to the BBC''s live radio broadcast. But as he approaches the end of his assault, the speech suddenly dissolves into incoherence when he stumbles over a name - a name he normally takes such pains to avoid - that takes him back forty years to a special time and a special place. Summer in February is a disturbing and moving re-creation of a celebrated Edwardian artistic community enjoying the last days of a golden age soon to be shattered by war. As resonant and understated as The Go-Between, it is a love story of beauty, deprivation and tragedy.

Release date: July 26, 2012

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Summer In February

Jonathan Smith

problem hearing it, and it was clear and crisp enough for everyone sitting at the top table. But then those about to speak

in public – as you’ll know if you’ve ever done it – are always on the edge of their seats, waiting for the moment to arrive,

picking at their food, wanting the lavatory, as dry-mouthed as jockeys lining up for the start at Newmarket, all tensed up

and ready for the off, and conscious that the eyes of the world are about to be on them.

And, in the President’s case, thousands of ears.

Not that he was nervous. Not a bit of it. If he had been nervous he would have written the whole speech out, wouldn’t he,

instead of just jotting down a couple of phrases on the back of his menu while enjoying his dinner to the full. Food and drink,

the President always maintained, were there to be enjoyed, and the truth was he was looking forward to this speech, to his

swansong: he knew what needed to be said to the assembled company and, by God, he was going to say it.

He was under starter’s orders.

But!

But, the table-tapping, while loud enough for him, was little match for that large gallery full of all-male banter, and no

match at all for the distant, well-oiled laughter which rose to the ceiling with the cigar smoke. The younger academicians

on the far tables, who had half heard the toastmaster tapping, pretended, in the time-honoured way, that they had not; and

when he was sitting in their place many years ago, the President used to do the same thing, employ the same delaying tactics,

only a damn sight worse. So, seeing the distant diners were not going to shut up for that genteel top table tapping, he turned

round and told the toastmaster to try again, only this time to ‘put a bit of beef into it’. And the toastmaster, a man of

solid muscle and bone, took the President at his word and fairly hammered the gavel. He hammered it slowly and loudly, with

more than a bit of come-on-gentle-men-now-please.

And that, the extra volume plus the emphatic pauses, did the trick. Even the rowdiest table fell silent; and once the lull

was established, the toastmaster, resplendent in red, puffed out his barrel chest and projected his voice full blast over

everyone’s heads, past the paintings hanging two or three deep on the walls, through the mahogany doors and out into Piccadilly

itself.

‘Your Royal Highness,’ he intoned – and that word ‘Highness’ helped to do the trick, bringing a respectful hush – ‘Your Excellencies,

Your Graces, My Lords and Gentlemen – Pray Silence for the President of the Royal Academy, Sir Alfred Munnings.’

Yes, that’s him!

Pray Silence for the second son of a Suffolk miller, a son of the soil, but then Constable, the great Constable, was the son of a Suffolk miller too, and who wouldn’t be as proud as Punch to follow in his footsteps?

There was, too, something about the toastmaster’s style that the President liked. Good toastmastering, he always maintained,

was like gunnery practice: you cleaned the barrels, you slammed in the shells, you got the trajectory right, and then you

discharged a deafening salvo at the enemy. Take aim, fire! and the enemy were brought down. Enemy? At a banquet in Burlington

House?

What enemy?

But the enemy were there all right, and in numbers.

As the toastmaster intoned his phrases, the President savoured each and every word. He enjoyed each e-nun-ci-ated syllable.

Now that, he said to himself, is how to introduce a chap, straight from the shoulder, no mumbling, no beating about the bush.

‘Your Royal Highness’ – and there indeed was the Duke of Gloucester on his right, more or less upright if rather the worse

for wear—

‘Your Excellencies’ – and there were ambassadors from God knows which country at every table, including some Turk or other,

Mr Aki-Cacky, on Top Table—

‘Your Graces’ – yes, including the Archbishop of Canterbury himself who’d just been up on his feet wittering away – mixed

up with the odd Admiral and Field Marshal, he could see old Monty at the end of the table. Not to mention loads of lords and

plenty of gents, plenty of boiled shirts and stuffed shirts, plus a sprinkling of pansies who couldn’t tell a decent painting

from a pool of horse piss.

No, steady on now, Alfred, he said to himself, careful, old boy, you’re not in The Coach and Horses now, you’re in civilised

company, surrounded by The Great and The Good, and they’re here for a slap-up do and they’re also here, Alfred, to hear your Retiring President’s speech and, by God, they’re going to get it!

On the toastmaster’s final words ‘Sir Alfred Munnings’ there was some kind of welcoming applause, mostly from Winston and

those close by on top table, but enough in all conscience to suggest some kind of recognition of all he had done as President.

As the applause died down, Sir Alfred took one more gulp of wine, a bloody good claret he’d selected himself, and checked

his flies. All secure there, he stood up.

The banquet was in Gallery Three, Burlington House, Piccadilly, and the place was jam-packed with one hundred and eighty diners.

The President ran his eye around the candle-lit tables, then placed both his fists, knuckles down, on the white tablecloth.

It was a position he liked to adopt when speaking. Not only did it take some weight off his dicky leg, but the stance also

(he felt) suited his attacking style.

So, here he was.

And there they were.

The President faced the Academy; he would not be presumptuous enough to say ‘his’ Academy. And he faced them with the nation

listening on the wireless, thousands of good people from John O’Groats to Land’s End had turned on their sets, ordinary folk

who liked to hear the simple truth spoken in simple plain English.

So, the truth it was to be.

‘Your Royal Highness,’ he began slowly, ‘My Lords and Gentlemen.’ As was his wont, he took his time over each syllable. After

a good evening he always maintained it was only sensible to take your time; it was always best to walk your horse home nice

and slowly through the lanes. Hurry along, as he’d found to his cost, and you could go arse over tip. The trouble was, though,

not only was he slow, he was too slow, and without meaning to, his voice caught some of the toastmaster’s tone.

‘I am,’ he began, ‘gett-ing some-what dis-tressed. Through some extra-ordin-ary arrange-ment these toasts have all been put

upon the Pres-i-dent.’

In amongst that lot there were too many rs and too many ps. Rs and ps could, the President knew, be a ruddy problem and if he didn’t watch it he’d soon be reciting Poe’s ‘Raven’ or running

round the ragged rock with the rugged rascals or whichever way round it was.

Pause, he said to himself. Pause, Alfred!

He paused. There was time now to take a quick look down at the notes he’d been jotting down on the menu card, so he lifted

it up close to his eye and saw

Casserole of Sole ChablisRose Duckling with OlivesGarden PeasNew PotatoesAsparagusGateau St HonoréIcesPetits FoisDessert& Coffee

and there was not a lot of help there if you were already stuck on your feet, but there also

was a rather good pencil drawing of Winston smoking his cigar, done not ten minutes ago. Damned good likeness it was too.

It looked like Winston, his heavily hunched shoulders, his wrinkled forehead, his big cigar, the old boy to a T., and that’s

what a drawing should do, shouldn’t it, look like the subject?

Pleased with this thought, emboldened by this conviction, the President launched himself again, only this time at a canter,

so to speak, pushing the horse on a bit.

‘I know what it is, and have known what it is, to sit at the tables when there has been a much more company’ – what? a much

more company, what does that mean? Never mind, no time, keep going – ‘ca-rousing and drinking, little thinking of the poor President there at his table,

regardless of all he had to go through, and to get away with, to put it in a common turn of speech.’

He breathed out. That sentence, while something of a mish-mash, went a lot better, though there was a nasty moment after ‘ca-rousing

and drinking, little thinking’, when he felt a touch of panic in his palms that he might be slipping into that familiar, bouncy

metre and that familiar rhyme, slipping in fact into one of his impromptu ballads.

But, dammit, he wasn’t in some snug pub or artists’ party reciting Edgar Allan Poe, he was the President of the Royal Academy

and all dressed up like a toff. He was the most famous figure in British Art, and the main thing was, he had to make sense!

He had to speak simple English!

‘Now here I am, responding for The Academy. Now the Archbishop of Canter-bury has talked’ … a load of complete … ‘in a very

accomplished way about this body … but what of the body?’

The body of men, he meant, the collective body of English Art, the packed tables laid out in front of him in Burlington House.

And he glared from table to table; he glared left, and he glared right, and he glared ahead; and he had to say he did not

like much of what he saw. He did not like it one little bit. It was high time a question was put to the collective body of

English Art, and put bluntly in front of the nation on the wireless. Then they couldn’t say they hadn’t heard it, could they?

Are they worthy? Yes, that’s it—

‘Are they worthy of this building in which they are housed? Are we all doing the great work which we should do? Well, it is

not for me to stand here on my head’ – head? You’re standing on your feet, Alfred – ‘here tonight and find fault with the Academy.’

At this there were some murmurs of approval, murmurs from posh people trying to warn him off, stuffed shirts trying to divert

the President into their polite, diplomatic channels. He could sense them saying under their breaths, ‘No, Munnings, you are

right, it is not for you, the second son of a Suffolk miller, to criticise us.’

This only incensed him further. Oh, wasn’t it! If they thought for one moment they could stop him going on with his plan they couldn’t be more wrong. In for a penny,

in for a pound, the President said to himself.

‘But, BUT I find myself a President of a body of men who are what I’d call shilly-shallying.’

He stressed ‘shilly’ and he stressed ‘shally’, and on ‘shilly-shallying’ a sizeable number of wobbly chins hit the table.

There was a sideways flickering of half-pickled eyes, a communal rolling of eyeballs. There was a fearful sense running around

the room that he was going to do it, and what was more he was going to do it with millions listening on the wireless. Damn

right he was. I told you I would, Laura.

He watched a white, manicured hand reach out in silence for the port.

Shilly-shallying. Monty, for one, liked that. Far too many soldiers, Monty always said, shilly-shallied. Winston, for another,

liked it. Far too many politicians, Winston said, and ‘so-called statesmen’ shilly-shallied. In the expanding silence the President once more glared round the room, not focusing

his eye on any particular place, merely allowing the accusation to sink in and hurt. The shilly-shalliers knew who they were,

and he knew who they were, and he was going to blow them to pieces.

‘They!’

His voice rose.

‘They feel that there is something in this so-called MODERN ART.’

When he said the fatal words ‘Modern Art’ there was a gasp, an audible gulp. Yes, Reynard the Fox was now out into the open

and running. Now it was clear the hunt was on. Suddenly – it also happened sometimes when he was painting – suddenly he felt

an extraordinary power, a quick pump of adrenalin, as if he was going full tilt along the Cornish coast or full split across

the flat Norfolk fields, whip in hand and cap askew, full tilt and fearless at a wide-open ditch. There wasn’t any point shying

away, you had to go for the jump.

His voice rose to a sharper, more competitive level.

‘Well, I myself would rather have – ah’ – if he was going to blaspheme he realised he had better be civilised, he really should

do the decent thing and turn and bow slightly to the Archbishop of Canterbury – ‘ah, excuse me, my Lord Archbishop – I would

rather have a damned bad failure, a bad dusty old picture where somebody had tried to do something, to set down something

what they have seen and felt, than all this affected juggling, this following of … well, shall we call it the School of Paris?’

That Paris crack, the way he put such contempt into ‘Paris’, just came out, he was enjoying himself so much. He was loving it. So he put his hands on his hips, exactly as Charlie Chaplin

did in The Great Dictator, and pretended to scour the tables for any offending French diplomats.

‘I hope the French ambassador is not here tonight.’

It has to be said he timed that aside rather well. In response, there was warm laughter, with-him laughter, and the aside

went down best of all with Winston, whose shoulders were going up and down. Good old Winnie, the President smiled, never a

great one for effete frogs and their new-fangled fashions. He looked at them all, and went strongly on.

‘Not so long ago, I spoke in this very room to the students, the boys and girls, and they were receiving all sorts of gratuities

from the Government. For what? For what?’

No one answered. No one dared.

‘To learn art. And to become what? Not artists. Well now, I said to those students, “If you paint a tree, for God’s sake try

and paint it to look like a tree, and if you paint a sky, try and make it look like a sky.”’ Winston, as sure as eggs were

eggs, was enjoying every word of all this: the President could feel his warm approval, there was absolutely no need to check.

Had they not discussed the textures of trees and the skyishness of skies often enough in recent months?

On he went:

‘Only this last two days I have been motoring from my home in Dedham to Newmarket and back. On Sunday I motored through Suffolk,

and I was looking at skies all the time … on Monday what skies they were! And still, in spite of all these men who have painted

skies, we should be painting skies still better!’

Skies! Not kittens with as many legs as a centipede. Skies! Not Picasso portraits, not females with two noses and three tits

and a set of shark’s teeth coming out of their earholes!

Yes, he was into his stride now.

‘But there has been this foolish inter-ruption to all effort in Art, helped by foolish men writing in the press encouraging

all this damned nonsense’ – and this time there was no apology to the Archbishop for ‘damned’ – ‘putting all the younger men

out of their stride. I am right … I have the Lord Mayor on my side … I am sure he is behind me … and on my left I have our

newly elected extra-ordinary member of the Academy, Mr Winston Churchill—’

—elected by me, that is, because he can paint a tree to look like a tree and he can paint a sky to look like a sky

—Winston Churchill elected by the second son of a Suffolk miller—

‘and I know Winston is behind me, because once he said to me, “Alfred, if you met Pee-cass-O coming down the street would

you join with me in kicking his something-something-something?” and I said, “Yes, Sir, I would.”’

Well, that was it! There was uproar. Uproar, no less. Alfred felt he’d done the trick, he had really and truly loosened up the whole show.

Gallery Three of Burlington House rocked. Waves of laughter rolled towards him from the back to the top tables. Down at his

end Monty was cackling away.

So that was fine. So far so good. But how was it going down with the pansies? What about the Blunts of this world, with their

manicured nails and their modulated voices and their porcelain expressions? What did they make of Winston and the President

lying in wait in some doorway for Pablo to come down Piccadilly in his beret so that they could jump out and kick him up the

arse? Eh?

The President was feeling in terrific form; he had never felt better.

‘Now,’ he went on, ‘we have all sorts of high-brows here tonight, ex-perts who think they know more about Art than the men who had to paint the pictures, even those poor devils who sit out and try to paint a landscape and fail.’

Because that, the President maintained, was how you should paint a picture, en plein air, as Bastien-Lepage said. It was as simple and as difficult as that. You needed all your colours, your white, your turps,

painting umbrella, rags, beautiful brushes, and with your hat over your eyes and your brushes in your mouth, you picked up

your easel and palette and canvas and went out into the open air in all weathers, wind, rain or shine, in Norfolk or Cornwall

or Hampshire, in peace or in war, you got outside and worked, that’s what he and Laura used to say to each other in Lamorna.

‘Get outside and work till you drop.’

And what did you paint?

Paint the real world, paint ordinary men and women, the land, the sea and the sky, not the sick world of some tortured spirit,

not the surreal world of some diseased and malformed imagination. But could you imagine those critics out in the open air?

Just imagine Anthony Blunt out in a field, with his eyes watering, his hands blue and with some dark storm clouds coming up.

Just imagine him covered in sultry summer flies. What would he do? He’d shut up shop and be back to his boys in his Chelsea

boudoir, well, bugger that lot if you’ll excuse the pun, because the President would prefer a basket-covered stone jar of

ale and an oak-ribbed bar, let’s say The Red Lion, some soup, fish and pheasant, or sausage and mash and briar pipes – that

was good enough for him, before the slow walk home.

Everyone could see he was enjoying himself. Any mention of the critics always brought the best out in Alfred.

The cri-tics.

‘They are so – if I may use a common expression – so fed up to the teeth in pictures, they move among pictures, they see so many pictures that their … they … their judgement becomes …’

At this point, as luck would have it, the President saw the offending article. His sight might not be too good these days

but he was sure the offending article was there, third table along at the far end, the Surveyor of the King’s Pictures. The

President didn’t plan it. He just said, ‘because their judgement becomes blunt, they, yes, blunt. And that reminds me, is

he here tonight? Anthony Blunt, is he here tonight?’

Oh, he’s here tonight all right and staring at his polished fingernails.

‘Who once stood in this room with me, when the King’s Pictures were here, and there was a Reynolds hanging there, and he said

“That Reynolds isn’t as great as a Pee-cass-O”. Believe me, what an extraordinary thing for a man to say! Well, perhaps one

should not mention names, but I do not care, since I am resigning at the end of the year.’

‘Good riddance!’ someone said.

The President’s blood jumped. His fists clenched. Who said that? Someone had, quite clearly, uttered the words ‘Good riddance’.

It wasn’t loud but he heard the words all right. His eyesight might be poor – and who could be surprised at that? – but his

ears were still damned good. ‘Good riddance’, eh? He could feel his knuckles grinding away into the tablecloth. He moved the

weight off his painful foot. His head started to beat, but he fought back.

‘I do not wish to go on with an Academy that says, “Well, there must be something in this modern art, we must give these jugglers

a show.”’

And what about that ‘woman’? Woman, my foot! Ask them about that monstrosity.

‘Here we are in this Academy, and you gentlemen assembled in the Octagon Room, and there was a woman cut out there in wood, and God help us if all the race of women looked like that!’

Yes, they enjoyed that, the diners did enjoy that. And the President enjoyed listening to their laughter, waves of it, good,

warm, male laughter, and they were laughing because they were all men together, and they all knew what a woman looked like,

and they all knew what they wanted a woman to look like, they wanted a woman to look paintable, but … did the pansies? Did the pansies? Come on, be honest, did the critics? No! What did the modern critics fancy? They fancied Modigliani’s models and Henry Moore’s

holes, Henry Moore’s modern heavyweight holes.

‘The sculptors today … are sinking away into a fashion of bloated, heavyweight, monstrous nudes.’

Blots on the landscape, bloated females, bloated, blote …

Blote—

Oh, Alfred, why did you say that?

His left hand started to tremble, then shake. He didn’t mean to use that word. It was a word he always avoided. He clenched

the tabletop to steady his hand, but the trembling would not stop. It was so easy to be put off one’s stride, wasn’t it, even

when things were going so well. Bloated. He had to blot out all bloated things. But he couldn’t. He could see her face, her

pale face. It was such a silly name, the very last name you would give a beautiful, paintable, elusive girl, but it clung

to her and it clung to him, like anemones to rocks.

There was silence and cigar smoke. But you couldn’t have silence in a speech, could you? If he didn’t speak soon they would

think he’d suffered a stroke. He had to keep talking. He could feel the room changing, he could sense a shiver in the subsoil, and the next thing he knew he was

on to ‘Battersea’, another B, oh bloody hell, and he gabbled on, but his heart was no longer in it. He was thrown, thrown off his horse, and he heard himself saying these sentences:

‘You saw those … things exhibited in Battersea Park? Did you? Things put there by the London County Council. We are spending millions every year

on Art Education, and yet we exhibit all these foolish drolleries to the public. And yet I have stood in that park, and I

have been with the public who’ve been there, I’ve asked them questions, and they were disgusted and angered, just as they

were to see this Madonna and Child in a church at Northampton.’

Henry Moore’s monstrosity, they all knew what he meant, Moore’s monstrously modern holes.

‘Because … I would like to ask everybody here to travel up to Northampton to see this statue of the Madonna and Child at this

church. I am speaking plainly because my horses may all be wrong, but I’m damned sure that statue isn’t right!’

At this point there was a kerfuffle at the far end of the gallery. Three or four chairs were being pushed back. Was it a protest

against the President and what he was saying or a brace of weak bladders? The President could not be sure, but it further

sapped his strength.

Stop now, Alfred, he said to himself, you’ve said enough, probably more than enough.

‘Well, I’m not going on too long, Sirs … I would not go on any longer because I know a greater man than I is going to follow

me.’

Mr Winston Churchill, no less. And you cannot get greater than that.

But he didn’t sit down, because he had not yet mentioned Mr Matisse. He had to get Mr Matisse off his chest.

‘But I would like to say that this afternoon I went to the Tate Gallery, the Tate, the second room on the right with white walls, which is nothing but walls, and you will see this picture

by Ma-tisse. It is called Le Foret … the … forest.’

And damn me if it didn’t happen again, and in much the same part of the room, only louder this time. More chairs moved. Mentioning

Matisse had done it. This time their voices were louder. The critical geese were gobbling and honking and stretching out their

. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...