- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

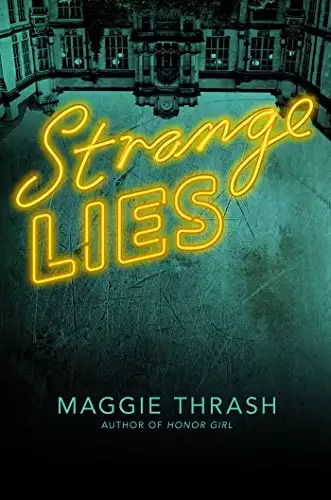

Critically acclaimed author Maggie Thrash’s second novel in the Strange Truth series blends crackling suspense, subversive humor, and biting social commentary to become the “definition of a page-turner” (John Corey Whaley). Only at Winship Academy would an evening science expo turn into a criminal fiasco. First, there’s the anonymous boy in the girls’ bathroom handing out drugs to anyone with the secret password. Then the student body president is maimed in a horrifying and tragic accident—but was it an accident or an attack? Benny Flax and Virginia Leeds are right at the center of it all. And so is the headmaster’s son, Calvin Harker, an oddball poet whose interest in Virginia sets off alarm bells for Benny. As the case bleeds from Winship Academy to the surrounding city, the deep fault lines of racial tension in Atlanta’s history reveal explosive hatred still simmering under the city’s surface. Once again, Maggie Thrash (author of Honor Girl) delivers a uniquely compelling, thought-provoking, and entirely riveting story.

Release date: October 16, 2018

Publisher: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Strange Lies

Maggie Thrash

One week earlier, Thursday

Yasmin Astarabadi’s house, 6:00 p.m.

She’s gone.

Yasmin Astarabadi’s entire body buzzed with megalomaniacal glee. Zaire Bollo was gone. According to Virginia Leeds, who was supposedly there when it happened, she’d run off to Spain and was never coming back. Of course, Virginia was an insane pathological liar and normally Yasmin wouldn’t pay attention to anything that girl said, but an entire week had gone by with no sign of Zaire at all. Then a truck had pulled up to the Boarders and hauled all Zaire’s stuff away—her gold-and-black wardrobe from Milan, her mountains of books, her imported stationery and tins of tea—everything. She was gone.

Carefully, and with great reverence, Yasmin removed Zaire’s photo from the large bulletin board on her bedroom wall. A web of ribbons came away with it, leading to index cards with words like “SATs,” “Governor’s List,” “Summa Cum Laude,” “clubs,” and “yearbook” typed in color-coded ink. She placed the photo faceup in the trash can. The next time she threw away some chewed gum or a Kleenex with a dead bug in it, she wanted it to land right on Zaire’s annoying, haughty face.

“Another one bites the fucking dust,” she said, delighted by her own corniness. She repositioned the remaining photos on the board, moving each one up a position, like horses in a race: Calvin Harker now at number one, herself at number two, Benny Flax lagging slightly behind her at number three, and DeAndre Bell behind him at a distant fourth. Now that Zaire was gone from the board, its quotient of physical beauty had dipped severely, Yasmin couldn’t help but notice. DeAndre was arguably handsome, but his smarmy, politician’s perma-grin ruined him in Yasmin’s eyes. As for the rest of them, Calvin Harker was lean and grim and ghoulish. Benny Flax was okay-looking, but dopey and distinctly hopeless. And if Yasmin contributed any beauty to the group, it certainly wasn’t evident to her. They were three ugly nerds.

Whatever, she thought. Beautiful people were stupid. That was a literal fact. Their brains developed differently, growing larger in the areas dedicated to reinforcing self-worth through the affirmation of others. It’s what made people think it was valuable to spend thirty-five minutes on their hair in the morning. That was thirty-five minutes Yasmin could be spending reading Sun Tzu or researching political internships. Time management was the key to life. Yasmin considered any moment in which she was not actively engaged in the advancement of her goals to be a quantifiable loss.

It wasn’t a coincidence that the top students in their class were all minorities in some way. The white kids at Winship didn’t bother competing academically. They would get whatever they wanted in life whether they had the grades to back it up or not; their fourth-generation country club connections were the only currency they needed. Yasmin felt sorry for them. They would never know the powerful, ecstatic satisfaction that she felt at having to work hard to distinguish herself.

Yasmin gave herself a quick once-over in the mirror. She didn’t like her outfit. On non-uniform occasions at Winship, you had basically one option unless you wanted to look like a freak: a cardigan set (color of your choice) with a short black skirt. In the spring and summer you could wear floral, but obviously not past Labor Day. Preppy outfits were always designed to exhibit—never overshadow—the assumed natural radiance of their wearer. On Yasmin, they looked average and drab, but she didn’t second-guess her choice. Being different just wasn’t worth the hubbub.

She gathered up the materials for her high-voltage electric arc. Tonight was the science expo, which excited Yasmin more than any football game or dance. Academic events were basically popularity contests of the brain. And now that Zaire was gone, Yasmin had a shot at actually winning.

She took a last glance at her newly organized bulletin board. Calvin Harker would be tough to beat. He was almost two years older than everyone else in the sophomore class. He’d had to drop out of school for ten months because he had heart cancer or a brain tumor or something. By all rights he should have been a junior. It wasn’t fair.

At least Benny Flax wouldn’t be a problem. He was smart and had great grades, but his heart wasn’t in the race. All he cared about was his little baby club about Blue’s Clues or whatever it was. What a waste of a good mind.

DeAndre made her nervous. His grades weren’t a huge threat, but he was the student body president, which would carry a lot of weight with the cocksuckers at Harvard. She knew for a fact that every decent college had been sniffing around him since ninth grade, when he’d taken the football team to state.

Whatever, she thought again. The word was her talisman. With it she’d surmounted the indignities of ninth grade, which had included an assault of acne and the realization that high school didn’t magically make boys interesting—they were the same annoying dipshits they’d been in middle school, only bigger, and if Yasmin ever wanted to have sex with one of them she’d have to dramatically lower her standards. Not that sex was even a remote priority for Yasmin. The only climax that mattered to her was making it to the top of the class—that gleaming, perfect pinnacle—where she’d grin down at everyone she’d crushed to get there.

Outside the gym, 6:30 p.m.

Benny felt like an imposter. He always did on these occasions.

It was the clothes—khaki pants, blue blazer, tie. The outfit wasn’t mandatory, technically, but it’s what every guy would be wearing. It wasn’t what he’d planned to wear. He’d planned to wear his dad’s gray wool suit, which had been hanging in the closet since the accident, immaculate and untouched. It was still in the plastic bag from the dry cleaners. The crease in the trousers was as perfect as if it had been ironed yesterday, not eighteen months ago. Seeing it, Benny had stopped. He wasn’t really going to wear this, was he? This was a man’s suit, and he was just a kid. What if it didn’t fit? What if he messed it up or spilled punch on it? What if his dad needed it? That last question was ridiculous, Benny knew. Benny’s dad had severe brain damage from a plane crash and wouldn’t be needing a suit tonight or possibly ever again. But still, what if he suddenly felt better and wanted to go out for a nice dinner in his suit, and when he went to the closet it was gone and the shock sent his brain back into its foggy maze? The idea was ludicrous, but as soon as it had germinated in Benny’s mind, he knew he wouldn’t be touching that suit.

He sat on the curb outside the gym, waiting for Virginia Leeds to appear. They were going to the science expo together. It was not a date, as if that needed to be established. He’d never heard of anyone going to a science expo as a date. He wasn’t exactly sure why they were going together at all. Ostensibly it was for Mystery Club, but really it was just a habit they’d developed of meeting each other places—in the hall after assemblies, by the apple stand during break, in the cafeteria if they had the same lunch period. They’d report any unusual observations—usually there weren’t many—then they’d go their separate ways.

Benny had founded Mystery Club on the basic philosophy that mysteries were everywhere, and that the greatest advantage in solving one was to Be There. Be watching, be a witness. Don’t wait for mysteries to come to you, because they won’t. Benny had learned this quickly enough. When he’d first created the club, he’d expected to be barraged with inquiries: Who started that rumor that I tongue-kissed a dog? Who put a bag of peanuts on the peanut allergy table in the cafeteria? Weird things were always happening at Winship, but people seemed too self-absorbed to care. Except for Virginia. Virginia cared—cared too much maybe. She was obsessed with other people’s business and always had been. Sometimes Benny wondered if she’d only joined Mystery Club as an excuse to spy on people.

“Hey.”

Benny twisted around and saw her approaching. She was wearing a soft black sweater and a gold skirt that Benny recognized as having belonged to Zaire Bollo. It looked expensive, and was short enough to glue anyone’s eyes to her legs. It was definitely inappropriate for an academic event that was mostly a spectacle for parents. Benny’s own mother was already inside, examining every tenth grader’s project to assess the competition.

Benny was about to stand up, knowing there was no way Virginia could sit on a street curb in that skirt without flashing the entire world. But Virginia either didn’t know or didn’t care. She plunked down next to him, immediately scooching away a bit, apparently having misjudged how close to him she’d landed. Benny stared ahead. Just because her underwear was probably showing didn’t mean he had to look. In fact, it was his duty not to.

“You look like a calculator salesman,” Virginia said.

“I look the same as everyone,” Benny said, nodding toward a very athletic, sandy-haired boy climbing out of a blue Mazda who was wearing the same combination of khakis and blue blazer as him.

“Oh yeah, you’re clearly twins separated at birth.”

Benny gritted his teeth. Virginia always managed to blithely zero in on whatever anyone was insecure about and broadcast it to the world. Did she do it on purpose? Benny didn’t know. Perhaps she’d enjoy it if Benny pointed out that she was wearing Zaire Bollo’s designer cast-offs and her underwear was showing. At least I didn’t steal my outfit from a murderer, he imagined saying back. But he knew he wouldn’t. It might feel good for a second, but then Virginia would get that crinkled, hurt look on her face, and Benny would be consumed by guilt for days.

Clothes, clothes, clothes, he thought dismally. These events always revolved around clothes. Winship was a uniform school, which meant that on the occasions when people had free reign to wear what they wanted, it became a matter of intense public display and scrutiny. The irony was that everyone ended up dressing the same as one another anyway, but as a collective decision rather than a mandate from above, which seemed to be an important distinction.

Virginia was picking at a large scab on her knee. She’d been picking at it all week. It was never going to heal at this rate, and the skin around the scab was red and infected. Benny was about to say as much when she sat up abruptly and began digging through a small brown bag that didn’t match her outfit at all.

“So, um, I got you something.” Virginia handed him a small velvet box. Benny examined it warily.

“What is it?” he asked. The last time she’d gotten him a present, it was a bracelet with the letters W.W.B.D.? (What Would Benny Do?) sewn onto it, with a matching one for herself. It had been touching but embarrassing.

“Just open it,” Virginia insisted.

He snapped open the box. Inside was a silver ring. He turned the ring over in his palm and saw that it was composed of a pair of dials, one engraved with letters and the other engraved with numbers. It looked expensive.

“It’s a decoder ring,” he said. “Wow, thank you.”

“I got us both one!” She held up a second ring. “For writing messages. You’re always complaining about the notes I leave on your locker, so . . .” Her voice trailed off, and Benny saw that her cheeks were bright red.

Benny had always found Virginia somewhat irritating-looking: her heart-shaped face prone to flushing, her blank staring eyes, her Afro of blond curls. But in the warm evening light, her features seemed to morph slightly, her face at some middle point between an awkward, chunky cherub and a Renaissance angel. It was an undeniable flash of . . . cuteness. Benny didn’t like the word—it evoked ponies and puppies and cupcakes—but there it was.

“You need to learn to control that,” he said, a little louder than he’d meant to.

“Control what?” Virginia said, turning her face away.

“Your cheeks. You’re blushing. If you want to be a great detective, no one should ever be able to tell what you’re thinking.”

“Oh yeah?” Virginia snapped, looking at him suddenly. “What am I thinking?”

Now Benny was the one blushing. “I . . . I don’t know. I’m just saying . . .” He stared down at the decoder ring, pretending to be fascinated by the dials. He could sense that Virginia was glaring at him. Seconds passed.

“So, what’s your project?” Virginia asked, back to picking her scab.

“A study of anomalous recoveries from neurological damage. What’s yours?”

“ ‘Trees of Georgia.’ I dunno. I suck at science.”

Virginia’s wouldn’t even be the worst project, Benny knew. The science expo was mandatory for all students. Winship’s science program had recently been called “lacking” in the Guide to Southern Prep and Boarding Schools, a slander the administration was obsessed with correcting. But by making the expo mandatory, the result was that people who had no business contributing clogged up the works for the people who were serious. Still, Benny tried not to be bothered. He believed in inclusivity and that everyone deserved a chance. But at the same time, he couldn’t help noticing that the chance seemed to be wasted on 99 percent of humanity.

He stood up. “I better go set up my booth. See you later.”

“See ya.”

“Um, thanks for the ring.” Benny made a small show of sliding it onto his finger.

“You’re welcome,” Virginia said back, not looking up from her scab.

Benny lingered a second, then gave up. He’d screwed up the moment somehow, and now it was over.

Booth 43, 7:15 p.m.

DeAndre’s project was the classic volcano. Classic was his thing. He’d seen all the Cary Grant movies as a kid and thought, with profound awe, That’s who I want to be. Cary Grant encompassed everything suave and cool. He was the ultimate leading man, and DeAndre channeled him in all things. Would Cary Grant go overboard with his science project? Nah, he’d do the bare minimum, but do it perfectly. Would Cary Grant be upset that the entire school was laughing at his uncle? Nah, Cary Grant would grin and brush it off. He’d probably laugh, too!

It was hard to keep grinning, though. The thing with his uncle was getting out of control. His whole family had come up from Lakewood Heights to see the science expo, even though he’d practically begged them not to. His mom had seen Winship before, and she knew how to be cool, but the rest of his family had predictably freaked when they’d seen the facilities—the soaring brick buildings, floor-to-ceiling windows with views of the football field and the river, shining tile floors, bathrooms bigger than their entire house, with automatic toilet-seat covers and mild-smelling foaming soap instead of the standard antibacterial pink goo. It was bad enough that they’d wandered around with their mouths hanging open like they were touring the White House. But then his uncle Jeffrey saw the spread at the refreshments table and exclaimed with loud glee, “They got real ham biscuits!” which had taken approximately five seconds to become a school-wide joke. Ten years from now, people would probably still be ribbing each other and saying, “They got real ham biscuits!” long after DeAndre was gone and the joke’s origin was forgotten.

Be glad to have contributed to the school’s history, he told himself. Cary Grant was always buoyant in these situations. He wouldn’t let an embarrassing uncle get him down. And if Uncle Jeffrey thought it was weird that about three different kids had come up and asked him if he’d seen that there were real ham biscuits at the refreshments table, he didn’t show it. In fact, he seemed delighted that Winship students were such attentive hosts. He slapped their shoulders congenially and said to each one, “You fuckin’ bet I did!”

The three judges appeared, and DeAndre got ready to make the volcano erupt. A group of students, mostly girls, were hovering nearby, obviously less interested in his volcano than in gawking at his family. DeAndre pretended not to realize this and greeted them warmly.

“Hey, guys! Come on in!” He was good at bringing people together. As the student body president, it was pretty much his job. A few weeks ago when everyone thought Brittany Montague was dead, it was DeAndre who had stepped up to organize the candlelight vigil, while everyone else was dissolving into despair.

“Come watch!” he said again to the girls.

“Um, okay!” They came forward, everyone smiling now. If you’re nice to people, they’ll be nice back, he thought happily. It was the simplest truth in the world. Why didn’t people get it? Sure, it could be hard sometimes. Kids at Winship weren’t known for welcoming outsiders. But if you were nice, and you weren’t a huge nerd, life at Winship could be pretty all right.

He poured vinegar into the crater and the papier-mâché mountain overflowed with burbling lava. His parents clapped and his little sister shrieked adorably.

“Great job, D!” Mr. Rashid said. “Wow. What a crowd-pleaser!”

Two girls were whispering to each other next to the volcano. “Omigod, did you hear about Virginia and Skylar?” DeAndre wiped up the table with a paper towel, trying not to look like he was listening. Gossip was in poor taste, but it was important to know what was going on in the lives of his constituents. But then Uncle Jeffrey appeared with a heaping plate from the refreshments table.

“You gotta get some of this shit, D!”

“I sure will, Uncle J,” he said, and by then the girls had left.

“Death. Death. Black band leader of endless night.”

DeAndre rolled his eyes. It was Calvin Harker again, in the booth across the row. Apparently his project was on morbid poetry or something.

“Hot spewing magma hardens to igneous rock. The blaze of life snuffed by ash.”

Oh god, please don’t drag me into this, DeAndre pleaded in his mind. Calvin used to be fairly normal, despite being freakishly tall and also the headmaster’s son, which was a serious social hurdle. But lately it was like he’d given up completely. DeAndre prided himself on never being cliquish or rude, but people like Calvin got on his nerves.

I can’t help you if you insist on being weird.

“No fire is eternal. Even the sun will burn out, our planet left an icy, forgotten globe.”

Booth 29, 7:30 p.m.

Why is everyone so willing to be boring?

It was a question Virginia asked herself almost every single day. Why did anyone do homework? Or wear navy? Or date the same person for three years? The other day in Ethics class, they’d gone around the room saying what everyone wanted to be when they grew up, and Corny Davenport said, “A real estate agent, just like my mom!” It was pretty much the most depressing thing Virginia had ever heard.

She’d been looking forward to the science expo all day. In her mind she’d conflated it with a dance somehow, imagining dim lighting and the promise of romance, except with science projects everywhere. Only now was she realizing how non-conducive to romance the science expo environment was. The gym’s fluorescent lights assaulted every corner. It was loud, and the roving panel of judges were making everyone uptight. This was going to be as boring as school, wasn’t it? Except worse, because at least at school you didn’t normally have to be around a hundred million parents.

On the “Trees of Georgia” poster she’d made, several of the dried, crumbling leaves had fallen down, and another was lopsided. She’d known it wasn’t a great project, but now it seemed actually pathetic. As she looked around, some of the other projects seemed barely even related to science. A group of juniors were doing a project on The Fast and the Furious that was just pictures of exploding cars and Vin Diesel quotes. And Trevor Cheek had a project called, simply, “Hunting,” which was showing off all the heads of deer he’d killed. If Virginia had known you could just do whatever you wanted, she would have done a project on classic cocktails, or Body Language of the Rich and Powerful.

In the booth next to her, Yasmin Astarabadi was erecting an immense pair of metal wires, one of which kept drooping perilously toward her. Virginia leaned away, not wanting her outfit to get stabbed. It felt different, wearing expensive clothes. It made her more conscious of her posture and of potentially ruinous stabbing wires. She’d never cared about perfect clothes before, but she loved this outfit and would probably literally cry if anything happened to it. You couldn’t find clothes like this in Atlanta. All of Zaire Bollo’s clothes had come from Paris and London and Milan. And back to Paris and London and Milan they’d gone after Zaire failed to return from fall break—except this one particular outfit, which Virginia had swiped from her closet and intended to wear as often as possible until she grew up into a person who bought clothes like this all the time.

“What is that?” she asked Yasmin, who was bending the wire back into place.

“A high-voltage traveling arc,” Yasmin said, not looking up from her weird equipment.

“What does that mean?”

Yasmin sighed impatiently and gave a long answer involving the words “cathode voltage drop” and “heated ionized air.” Virginia wished she hadn’t asked.

On the other side of her, Lindsay Bean had a project called “Pudding Inventions,” which seemed to involve making pudding out of the grossest flavors imaginable, like seaweed and diet popcorn and lobster. Sophat Tiang and Skylar Jones, the biggest stoners in school, had wandered over to sample them. Virginia tried to look busy putting the falling leaves back on her pathetic poster. Skylar acted like she wasn’t even there.

Hello? Virginia thought, getting annoyed. Skylar always ignored her as if they hadn’t totally had a thing last year. Not a huge thing, but enough of a thing that she deserved some respect from him. She’d only liked him because he seemed different from everyone else at Winship. He wore sandals, and a hemp necklace, and had once said, “I’d rather have a bottle in front of me than a frontal lobotomy,” which Virginia had found unbelievably clever until someone told her it was a famous quote.

“Is it going to explode?” Skylar was asking Lindsay. He was grinning and pointing at a cylinder full of white frothy substance.

Lindsay giggled. “Maybe!”

“It looks like jizz. I think it wants to be released.” Skylar and Sophat laughed. Skylar reached across the table and rubbed the cylinder up and down obscenely.

“Skylar, stop. Skylar! Don’t!” Lindsay squealed. Virginia considered giving Skylar a shove to make him quit, but then decided it was better to remain aloof from his gross immaturity. Lindsay could fend for herself. But then, as she was turning back to her leaf poster, she heard a squishing noise and felt a hot thick liquid all over her neck.

“Ew!” She touched her shoulder and her fingers came away sticky with a white, fishy-smelling goo. Skylar and Sophat were slapping each other’s backs and laughing hysterically.

“Skylar, you moron!” Virginia hissed at him.

“Was it good for you, too?” he said, grinning hugely.

Virginia turned to Lindsay and pointed to the nasty white smear covering half her sweater. “What the hell is this?”

“It’s lobster paste.”

Skylar laughed even harder. “What can I say?”

Virginia grabbed a paper towel from Lindsay’s table and started dabbing at the ugly splotch. She felt angry tears sting her eyes. Does lobster paste stain? She felt like kicking Skylar in the balls, but what if she didn’t kick hard enough and accidentally gave him a boner or something? It was just impossible, trying to get the upper hand with boys.

Skylar and Sophat had moved on to poking Yasmin’s gigantic metal wires. Yasmin was ignoring them and messing with a transformer box. Nerds like Yasmin were used to this kind of thing, Virginia figured. They just conducted their lives as best they could amid constant disruptions from people who couldn’t build anything of their own, so they tore everyone else down. She couldn’t decide which side of the dynamic was more pathetic. Virginia grabbed more paper towels and started toward the bathroom, dabbing at herself.

“Wait!” Skylar shouted at her, suddenly not laughing anymore. “Are you going to the bathroom?”

Virginia paused. Why did Skylar care if she went to the bathroom or not? Was he going to invite himself along? She glanced at Yasmin, who was giving her a blank, weirdly hostile look, as if to her, she and Skylar and Sophat were all the same. I’m not with them, Virginia wanted to tell her.

“You don’t wanna go in there,” Skylar was saying, his face serious. Sophat and Yasmin looked from him to her, like something was about to happen.

Virginia narrowed her eyes. “Why, did you do something gross?”

“No,” Skylar said. “Just trust me, dude. Don’t go in there.”

Virginia tossed her hair and kept walking. You couldn’t take anything that loser said seriously. But then, the second she crossed into the hall, she sensed a shift in the air. It was quieter, and brighter. The hum of four hundred voices was instantly muted. Without daylight streaming through the windows, the fluorescent lights gave the white walls an eerie glow. A group of girls was huddled by the water fountain, talking in urgent whispers. They looked like paint swatches, each with a different vibrantly colored cardigan set. Virginia walked past them and was almost at the bathroom door when she heard her name.

“Virginia,” one of them was whispering. “Virginia, don’t go in there.”

Booth 33, 7:30 p.m.

Benny stood surrounded by brains. His project was called “Mind Over Matter,” and it was a case study of brain-damaged patients who had “miraculously” overcome incredibly grim prognoses.

Mrs. Flax was not happy. Benny had been vague about the topic of his project, knowing she would disapprove. Some of his own father’s brain scans were mixed among the ones he’d copied from neurological textbooks, and he knew his mother would recognize them. The unique purple splotch representing the damaged area of his cerebrum was distinct. To Benny it resembled a ghost leaning forward against a brutal wind. Mrs. Flax had never expressed precisely what she found objectionable about Benny’s interest in his father’s recovery. But he’d gotten used to a certain expression on her face: a vague, tired sneer, the face of someone exhausted from dealing with a child who insists on being stupid.

Benny read his concluding thoughts from an index card: “In summation, ‘medical miracles’ do not exist. This concept is left over from our superstitious past. Advancements in medical science will prove that every ‘miracle’ has a logical explanation.”

No one clapped. Hi

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...