Man as the Measure of All Things

1944

Somewhere in the Tuscan hills, two English spinsters, Evelyn Skinner and a Margaret someone, were eating a late lunch on the terrace of a modest albergo. It was the second of August. A beautiful summer's day, if only you could forget there was a war on. One sat in shade, the other in light, due to the angle of the sun and the vine-strewn trellis overhead. They were served a reduced menu but celebrated the Allied advance with large glasses of Chianti. Overhead, a low-flying bomber cast them momentarily in shadow. They picked up their binoculars and studied the markings. Ours, they said, and waved.

This rabbit's delicious, said Evelyn, and she caught the eye of the proprietor, who was smoking by the doorway. She said, Coniglio buonissimo, signore!

The signore put his cigarette in his mouth and raised his arm-part salute, part wave, one couldn't be sure.

Do you think he's a Fascist? said Margaret quietly.

No, I don't think so, said Evelyn. Although Italians are quite indecisive politically. Always have been.

I heard they're shooting them now, the Fascists.

Everyone's shooting everyone, said Evelyn.

A shell screamed to their right and exploded on a distant hill, uprooting a cluster of small cypress trees.

One of theirs, said Margaret, and she held on to the table to protect her camera and wineglass from the shock waves.

I heard they found the Botticelli, said Evelyn.

Which one? said Margaret.

Primavera.

Oh, thank God, said Margaret.

And Giotto's Madonna from the Uffizi. Rubens's Nymphs and Satyrs and one more-Evelyn thought hard-ah, yes, she said. Supper at Emmaus.

The Pontormo! Any news about his Deposition?

No, not yet, said Evelyn, pulling a small bone from her mouth.

In the distance, the sky suddenly flared with artillery fire. Evelyn looked up and said, I never thought I'd see this again at my age.

Aren't we the same age?

No. Older.

You are?

Yes. Eight years. Approaching sixty-four.

Are you really?

Yes, she said, and poured out more wine. I pity the swallows, though, she added.

They're swifts, said Margaret.

Are you sure?

Yes, said Margaret. The squealers are swifts, and she sat back and made an awful sound that was nothing like a swift.

Swift, said Margaret, emphasizing her point. The swallow is, of course, the Florentine bird, she said. It's a Passeriform, a perching bird, but the swift is not. Because of its legs. Weak feet, long wingspan. It belongs to the order of Apodiformes. Apodiformes meaning "footless" in Greek. The house martin, however, is a Passeriform.

Dear God, thought Evelyn. Will this not end?

Swallows, continued Margaret, have a forked tail and a red head. And about an eight-year life expectancy.

That's depressing. Not even double digits. Do you think swallow years are like dog years? said Evelyn.

No, I don't think so. Never heard as much. Swifts are dark brown but appear blackish in flight. There they are again! screamed Margaret. Over there!

Where?

There! You have to keep up, they're very nippy. They do everything on the wing!

Suddenly, out from the clouds, two falcons swooped in and ripped a swift violently in half.

Margaret gasped.

Did everything on the wing, said Evelyn as she watched the falcons disappear behind the trees. This is a lovely drop of Classico, she said. Have I said that already?

You have actually, said Margaret tersely.

Oh. Well, I'm saying it again. A year of occupation has not diminished the quality. And she caught the proprietor's eye and pointed to her glass. Buonissimo, signore!

The signore took the cigarette out of his mouth, smiled and again raised his arm.

Evelyn sat back and placed her napkin on the table. The two women had known one another for seven years. They'd been lovers briefly in the beginning, after which desire had given way to a shared interest in the Tuscan proto-Renaissance-a satisfactory turn of events for Evelyn, less so for Margaret someone. She'd thrown herself into ornithology. Luckily, for Evelyn, the advent of war prevented further pursuit, until Rome that is. Two weeks after the Allies had entered the city, she'd opened the front door of her aunt's villa on Via Magento only to be confronted by the unexpected. Surprise! said Margaret. You can't get away from me that easily!

Surprise wasn't the word that had come to Evelyn's mind.

Evelyn stood up and stretched her legs. Been sitting too long, she said, brushing crumbs off her linen slacks. She was a striking presence at full height, with intelligent eyes, as quick to the conundrum as they were to the joke. Ten years before, she had committed her graying thatch to blond and had never looked back. She walked over to the signore and in perfect Italian asked for a cigarette. She placed it between her lips and steadied his hand as she leaned toward the flame. Grazie, she whispered, and he pressed the packet firmly into her palm and motioned for her to take it. She thanked him again and moved back to the table.

Stop, said Margaret.

What?

The light on your face. How green your eyes are! Turn a little to me. Stay like that.

Margaret, for God's sake.

Do it. Don't move. And Margaret picked up her camera and fiddled with the aperture setting.

Evelyn drew on the cigarette theatrically (click) and blew smoke into the late-afternoon sky (click), noticing the shift of color, the lowering of the sun, a lone swift nervously circling. She moved a curl of hair away from her frown (click).

What's eating you, dear chum?

Mosquitoes, probably.

I hear a touch of Maud Lin, said Margaret. Thoughts?

What is old, d'you think?

Cabin fever talking, said Margaret. We can't advance, we can only retreat.

That's old, said Evelyn.

And German mines, silly!

I just want to get into Florence. Do something. Be useful.

The proprietor came over and cleared their plates from the table. He asked them in Italian if they would like a coffee and grappa and they said, How lovely, and he told them not to go wandering again, and he told them his wife would go up to their room later and close the shutters. Oh, and would they like some figs?

Oh sì, sì. Grazie.

Evelyn watched him depart.

Margaret said, I've been meaning to ask you. Robin Metcalfe told me you met Forster.

Who?

Him with a View.

Evelyn smiled. Oh, very good.

The way Robin Metcalfe tells it, you and Forster were best friends.

How ridiculous! I met him across a dining table, if you must know, over dinners of boiled beef, at the ghastly Pensione Simi. We were an impoverished little ship on the banks of the Arno, desperately seeking the real Italy. And yet at the helm was a cockney landlady, bless her soul.

Cockney?

Yes.

Why a cockney?

I don't know.

I mean, why in Florence?

I never asked.

Now you would, said Margaret.

Now I certainly would, said Evelyn, and she took a cigarette and placed it between her lips.

Probably came over as a nanny, said Margaret.

Yes. Probably, said Evelyn, opening the matchbox.

Or a governess. That'll be it, said Margaret.

Evelyn struck a match and inhaled.

Did you know he was writing a book? asked Margaret.

Good Lord no. He was a recent scholar, if I remember rightly. Covered in the afterbirth of graduation-shy, awkward, you know the type. Entering the world with no experience at all.

Weren't we all like that?

Yes, I suppose we were, said Evelyn, and she picked up a fig and pressed her thumbs against the soft, yielding skin. I suppose we were, she repeated quietly.

She tore the fruit in half and glanced down at the erotic sight of its vivid flesh. She blushed and would blame it on the shift to evening light, on the effect of the wine and the grappa and the cigarettes, but in her heart, in the unseen, most guarded part of her, a memory undid her, slowly-very slowly-like a zip.

Strangely charismatic, though, she said, surfacing into the present.

Forster was? said Margaret.

When he was alone, yes. But his mother's presence suffocated him. Every reprimand was pressure applied to the pillow. Odd relationship. That's what I remember most. Her with a parasol and smelling salts, and him with a well-thumbed Baedeker and an ill-fitting suit.

Margaret reached for Evelyn's cigarette.

I remember he'd appear in quiet moments. You wouldn't hear him, just see him. Tall and lanky in the corner. Or in the drawing room with a notebook. Scribbling away. Simply observing.

Isn't that how it starts? said Margaret, handing back the cigarette.

What?

A book.

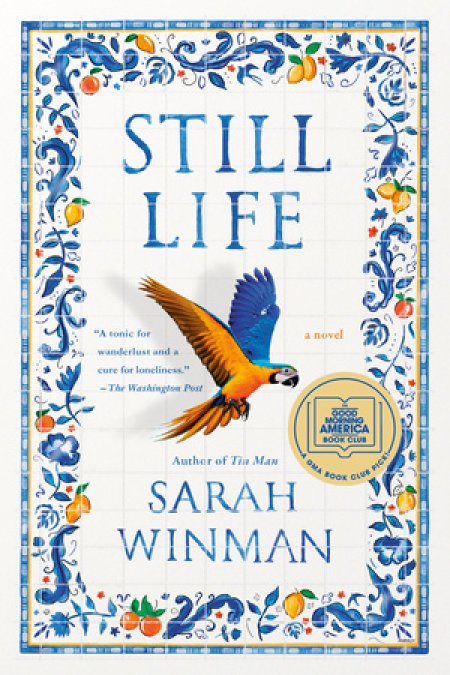

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved