- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

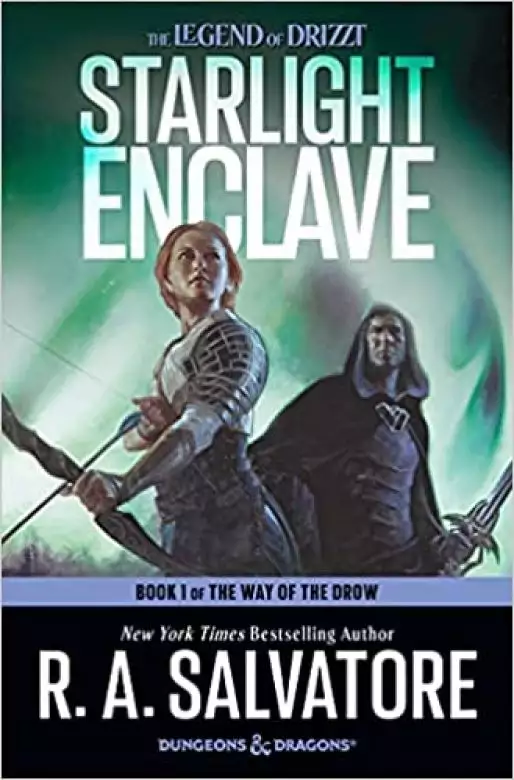

From New York Times bestselling author R. A. Salvatore comes a new trilogy and adventure of Drizzt and fantasy’s beloved characters from Dungeons & Dragons’ Forgotten Realms.

After the settling dust of the demon uprising and two years of peace, rumblings from the Menzoberranzan drow have Jarlaxle nervous. Worried his allies may be pulled into a Civil War between the great Houses, he is eager to ensure Zaknafein is armed with weapons befitting his skill, including one in particular: Khazid’hea. A powerful artifact, the sword known as “Cutter” has started wars, corrupted its users, and spilled the blood of many, many people. Nonetheless—or maybe because of that—the rogue Jarlaxle and a small group of friends will go on an expedition looking for the weapon’s last wielder, Doum’wielle, in the freezing north, for she may be the key to unlocking the sword’s potential…and perhaps the key to preventing the bloodshed looming over the Underdark.

And as they explore the top of the world, Drizzt is on a journey of his own—both spiritual and physical. He wants to introduce his daughter Brie to Grandmaster Kane and the practices that have been so central to his beliefs. But, having only recently come back from true transcendence, the drow ranger is no longer sure what his beliefs mean anymore. He is on a path to determining the future, not just for his family, but perhaps the entire northlands of the Realms themselves.

Two different roads. On one, Jarlaxle and Zaknefein are on a quest to find pieces that could offer salvation to Menzoberranzan. On the other, Drizzt seeks answers that could offer salvation to not just his soul, but all souls.

And no matter the outcome of either journey, the Realms will never be the same again.

Release date: August 3, 2021

Publisher: Harper Voyager

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Starlight Enclave

R. A. Salvatore

The Year of the Nether Mountain Scrolls

Dalereckoning 1486

Sleep seemed shorter and shorter. Why hadn’t twilight come? Where was the night? Had she missed it during her many naps?

Had she lost track of time itself? It seemed to her as if most of the day had passed before the sun had reached its highest point in the sky—and why was that highest point so far to the side? Was the sun circling her? Why was it circling her?

She knew that she used to know that answer, but now it just confused her.

None of it made any sense because none of it mattered. A longer time awake just meant a longer time to be hungry, and more time to be ready to run away from whatever animal or monster saw her.

That had happened a lot until she had gotten down from the mountainside and out onto this frozen plain—going south, so she had thought, but now was not so sure.

The sun wasn’t helping, but if she could just stay awake until the nighttime, she knew that she could navigate using the stars. It seemed, though, that no matter how long she tried to stay awake and moving,she couldn’t quite make it to anything resembling twilight, and no matter how short her sleep seemed to her—even on one occasion when she thought she hadn’t actually slept at all—the dawn’s light had already become daylight before she emerged from her cave or snow shelter.

Or maybe it was just daylight still, and not again, but that made no sense, except that it did, and she didn’t know where to go or how to go.

And now she was growing hungrier. Desperately so.

She had survived on the rich drow mushroom bread in her pack for a tenday, rationing it from the start as much as she could while still getting the nourishment she needed to trudge along barren terrain. She counted the meals to try to measure the passing days, and thus tried to estimate the distance she was covering, but those calculations, like everything else, had melted somewhere within the recesses of her thoughts, lost in the monotonous whistle of the chilly wind. More than chilly—it was cold. At first she had thought that was due to her elevation, but no, even with those mountain slopes far behind, it was still cold.

Now the bread was long gone. She had a bit of mistletoe, and used it to create magical goodberries each day or two, little orbs that nourished and replenished her and even healed any minor cuts or bruises she had suffered while trying to cross the brutal, seemingly lifeless landscape. But the mistletoe was not infinite, and she understood that it would not last much longer.

She was tired. She was confused. She was cold. She was lost.

She looked down at the crude spear she had fashioned, one of so many she had made in the days—or tendays . . . or months or whatever it might be—that she had been wandering this rugged, forsaken land. No, the sun hadn’t set, so it had to be hours, but how could it be? How could she have come down from that now-distant mountain in mere hours?

But where was the twilight? Where was the night?

She remembered her sword, her friend, her protector, her mentor.

Khazid’hea.

“Cutter,” she whispered through her cracked lips, the nickname of the powerful weapon. “My Cutter.”

But it wasn’t on her hip. She had only this spear, which was barely effective as a walking staff.

Refusing to die, living with the single thought of exacting revenge on the wizard who had thrown her through a portal to the side of that snow-covered mountain, Doum’wielle Armgo put one foot stubbornly in front of the other. She had to keep moving, had to find some alternative to her primary food source.

Then what?

Why wasn’t there anything to kill? Where were the animals? Where were the plants? She hadn’t seen any plants in days and days, not since she had left the foothills. Every now and again she spotted a bird, but none had come close enough for her to take it from the sky with a magical spell or a spear throw.

It didn’t matter. She had to keep moving, had to keep going the right way.

If there even was a right way.

She was almost certain she wasn’t walking in circles. In perhaps the only glimpse of insight remaining for the battered young half moon elf, half drow, she remembered the towering mountains were far away now, replaced by patches of rock in a sea of snow, lined with stony ridges like motionless eternal waves, a frozen painting.

Was that it? She wondered with all seriousness. Was she stuck in a painting? A frozen scape of lifelessness? Or, more likely, had she been thrown through Archmage Gromph’s portal to an unknown plane of existence, a place of frost and snow, of endless day where sleep couldn’t latch on as that weirdly arcing ball of light in the sky ceaselessly watched over her, taunting her?

Always taunting her! This was the world of her drow father turned upside down. The blessed darkness replaced by infernal white. She stumbled across the empty expanse, with one thought plaguing her.

Would she ever again see the night sky?

And then it happened. Hungry, her stomach growling, her berries growing less effective as the mistletoe waned, Doum’wielle at last watched the sun dip to start its journey below the horizon. She had to dig her nightly cave, she thought, and so she set to the task with the enthusiasm of knowing a full day was going to be rewarded with deserved sleep.

But the sky didn’t darken much at all, and she watched in blank amazement as the sun continued on its way, not lowering, not darkening, but rather, moving along the horizon.

And soon after, rising once more, the sun in the sky again! Or, not again.

Still.

She climbed into her hole. She tried to sleep, but knew she was doomed. This could not be her world.

“No,” she decided. “This is eternal torment for Doum’wielle.” It mocked her for her father’s drow heritage, she decided. It was a taunt, a forever taunt, punishing her for the sins of her father.

And Doum’wielle screamed and screamed into the wind, until she could scream no more and fell limp with exhaustion.

And she lay there and shivered. And sometime later, she ate a berry and came forth into the daylight.

She trudged on because she had no choice.

But neither did she have any sense of direction. Or hope.

She cursed the sun with every step, and praised any clouds that crossed the sky to dim it, and cheered aloud under the storm clouds on those few occasions they appeared, as if they were her champion in the battle with a fiery orb that would not relent to night.

Yet she was losing the war. Her mistletoe died. She could not make berries. She had no bread. She could make flame, which she did to keep warm and to melt some of this endless sea of snow so that she could drink. But it was temporary. And soon that magic would fade, too.

And then so would she. Fade into this windswept plain of snow and frozen waves of rock and ice.

Everything was different from what she knew. Everything was the same.

She drank more meltwater. She sheltered in caves she dug in the snow.

At one point, at some time that was the same as any other time, Doum’wielle came upon a crack in the ice, a chasm wide enough for her to descend. Weak and shaky, she removed her pack and climbed down, and down some more. A piece of ice broke off in her hand and bounced and tumbled far below.

She held her perch and held her breath, but began to wonder the point. Perhaps she should just let go and fall and die.

But then she heard a splash.

More curious than hopeful, Doum’wielle continued her descent and found some focus in her jumbled mind, enough to bring forth a magical light. With every movement down now, she cast another cantrip, a burst of shocking energy that cut the ice and made a solid handhold. She came at last to dark water, running as far as she could see along this narrow gorge.

It heaved and swelled, and Doum’wielle sensed that it was a wider body than the gorge, surely. She cupped her hand and took a sip, then spat it out, for it tasted of salt. She had traveled to the Sword Coast and the ocean before—this was not as salty, but neither was it potable.

But if this was indeed a sea . . .

Doum’wielle put her hand into the cold water and cast a minor spell of light to create a glowing area beneath her. Then another light, this time on a small coin, which she tossed into the water, watching the brightened area as it descended.

She waited.

She saw movement, just a flitter of a small form darting through the unnatural brightness.

Doum’wielle settled on a secure footing, digging holes with her lightning on either side of the narrow chasm where she could set her feet. She rolled up a sleeve, put light upon her hand, and bent low, then submerged her arm to the elbow, wincing at the sting of the cold water. She waited.

A distortion.

Lines of tiny lightning shot out from her fingers, a shocking grasp that became a small ball of stinging energy, and she yelped and retracted her hand. She was rubbing it and looking past it when she forgot all the pain, for a small stunned fish floated to the surface. She snatched it up and shoved it whole into her mouth, desperate for food, not caring about the bones or scales or that it wasn’t cooked.

Only caring to find more!

Time didn’t matter. Another fish, and a third, and she devoured both. Then another, and another, and she bashed them against the ice to stun them or kill them, stuffing them into her pockets.

And she waited for more, and thought that she might just stay here forever.

But no, how could she?

It took her a long time to sort that puzzle out, for she did not want to leave this place—how could she leave this place that offered food?

She lit and dropped another coin, then another after that. Then a large form moved through that lowering light. A much bigger fish. As long as her arm.

Doum’wielle pulled a fish from her pocket and bit out its belly, tugging out its entrails with her teeth, then tossed the squirming, dying mess into the water.

Up came the larger fish to feed, and down went Doum’wielle’s hand, grasping it, shocking it (and shocking herself in the water yet again!). She accepted the pain and cast the spell once more, then lifted the thrashing steelhead from the sea, viciously and repeatedly slamming it against the ice until it went still.

She loosened the fine cord of her belt and tied the prize to her waist, and then Doum’wielle, beyond pain, beyond exhaustion, somehow climbed up the same side she’d come down. She knew not for how long, or how far, or how many times she had to cast a minor cantrip to secure her grip, but at last she crawled back up onto the sea of snow and ice beside her pack.

The sun was still there to mock her.

She dug a small hole in the snow and crawled in, as much to get out of the relentless light as for the shelter offered against the chill wind, and for the first time in days—months? Years? An eternity?—she slept.

She ate the small fish when she awakened, stuffed the large one in her pack, and walked on, staying near to the chasm.

She had to keep moving.

She had to keep eating.

She had to keep moving.

She had to keep eating.

Move.

Eat.

Sleep.

Drink.

Her thoughts reduced to only that. She forgot why.

And why wouldn’t the night come? Where were the stars she had danced under in the . . . in the place before that now had no name in her memories?

Many times in that seemingly endless wander, Doum’wielle tried to recall her more powerful spells, but to no avail. At some point, she finished the last of the large fish, but was too weary to go back into the chasm, or perhaps she just forgot, and so she moved along, step after step in the glaring, unrelenting sunlight and the incessant cold wind.

She knew not how long after—she had slept four times, but that meant little—her belly began to growl again from hunger and her arms began to hang heavily at her sides. She ignored it for a long while, but then realized, to her horror, that she was no longer walking beside the large crack in the immensely thick ice pack.

She spun all around, trying to get her bearings, the shock of her suddenly more dire situation bringing a moment of clarity. She tried to retrace her steps, but already they were disappearing behind her in the constant swirl of blowing snow. She rushed about for as long as she could manage, but could not find again that chasm, that conduit down to the sea so far below her feet, to the fish that had sustained her.

She had no idea what she should do. She looked to the horizon, to the distant mountains, though she couldn’t tell if those were even the same mountains she had first landed upon. It didn’t matter, as any way was as good as another, so she locked the image of a distinctive peak in her thoughts.

“A straight line,” she told herself, though she wasn’t really sure why that might be a good thing.

And she walked on, and on, then slept and walked and slept some more.

Doum’wielle had come to understand beyond any doubts that many of the pieces of time that she used to call a day had passed when she realized that she was out of time and out of strength. The water from the melted snow was not enough anymore.

She fell to her knees and screamed at the sun, cursing it, demanding the night.

She wanted to die at night.

She didn’t even dig a hole to sleep in. She just fell down and the darkness of sleep came over her.

Then a deeper darkness.

Doum’wielle didn’t know how much time had passed when she opened her eyes once more, only to find herself in darkness. Cold, cold darkness.

She tried to get up, or roll over, but her cheek was stuck to the ice.

For the first time since she had walked from that mountain where Archmage Gromph had thrown her, Doum’wielle Armgo cried. She cried for her misery, for this miserable end. She cried for her betrayed mother, who had been left for the orcs by her father when he had chosen to walk with Doum’wielle into the darkness.

She cried for Teirflin, her murdered brother. What had she done? She pulled a hand up to her eyes, expecting to see his blood still upon it.

She tried to tell herself that Khazid’hea had made her do it, that the sword had selected a champion, and so she had been given no choice. But no, she couldn’t quite bring herself to blame the sword, or hate the sword, no. Never that. In the end, she wept, too, for Khazid’hea.

It should be in her arms, clutched to her as she left this world.

This dark world.

That last thought caught her by surprise. She tried again to lift her face, to turn her face, then, when that failed, she set her hand against the cold ice and pushed suddenly with all the strength she could muster, tearing herself free. The pain was excruciating, but the liberation was worth it. She stumbled and thrashed, winding up on her back and looking up at the sky, at the clouds and the stars.

The stars! A million, million stars!

The day had ended, at last.

With great effort, she pulled herself up to a sitting position, and felt the bite of the freezing wind more distinctly.

As a deeper cold crept in, she believed that she had awakened only to witness her own death, that her mind had somehow decided that she must be alert in these last moments.

She would lie down now and once again let the cold take her, she decided, for what choice did she have? But as she started to roll back, Doum’wielle noted a curious light low in the sky far to her left, a diffused yellow glow. Her first thought was that the sky was swallowing the sun, and that the night was winning some celestial battle here.

But then she realized that the glow was below the silhouette of the mountain range.

That could not be.

Somewhere deep in her thoughts, the word “campfire” whispered, and with it a memory that a campfire meant other people.

With the last strength within her emaciated, broken form, Doum’wielle crawled for that light. On and on, so long that she expected the sun to rise, and thought that there should be some predawn glow. But no.

Then the firelight flickered out before her, and she redoubled her pace, fighting, thinking every movement would be her last, feeling a coldness within her beyond anything she had ever known, so cold that she thought her hands and feet were on fire.

Head down, the withering, dying half elf almost crawled right into a mound of snow, and startled, she looked up and started to move around it—except that her mind couldn’t quite grasp what she was seeing. This was no natural mound, but a nearly perfect dome, and one with a low awning of sorts made of snow, creating an entrance tunnel.

Not even thinking of anything more than getting out of the wind, Doum’wielle crawled in. She froze when she felt fur, thick and soft, but after a moment of terror, realized that it was not a living animal but a thick blanket.

It was warm in here, warmer than it should be, she thought, for the walls, too, were of snow.

She didn’t understand.

She also didn’t care. She crushed her face into the fur and cried and let herself fall away from the world.

Until she heard a growl.

Her eyes popped open to see the pointy fangs of a snarling canine creature barely a finger’s breadth from her face.

She screamed and the creature half barked, half yelped at her, while another nipped at her from the other side. Doum’wielle screamed again and rolled, slapping desperately, turning about for the doorway . . . to find two forms blocking the entrance. Humans, she thought, and one holding a small lamp.

“Help me,” she started to say, until the larger of the two pulled back the furry hood of his heavy coat.

Definitely not humans.

Orcs.

Reflexively, Doum’wielle reached out a hand to grab at each and brought forth her lightning magic, shocking them both. She pushed them aside as they lurched in pain, and crawled for the tunnel and her very life.

Sharp teeth latched down on her foot, so she kicked at the beast with her free leg, but when she tried to bring that foot back, a powerful hand clamped down upon her ankle, grabbing and holding fast. Doum’wielle clawed with all of her strength. She dug her fingers into the ice and snow, crying and screaming, desperate to get away.

But she had no strength, and the orc tugged her back in so easily. She tried to turn, but the pair were on her, pulling at her, pinning her, their fierce pets yipping and growling, snarling and snapping at her feet.

The orcs were talking at her or to her or to each other—she didn’t care and just kept thrashing.

It was no use; she could not fight them. They had her held fast against the floor. They pulled at her clothes. They pulled off her clothes. They pushed her down on the fur where she had first collapsed.

Disgust filled Doum’wielle when she felt them come against her on either side, their filthy orc flesh against her own. She tried to resist, sobbing, until she could fight no more.

This was worse than the empty plain. Worse than the cold and hunger. She wanted to escape her body, expecting horrors.

But they just held her and pressed against her, and pulled another fur over them all, and the orc woman—for one of them certainly was female—began to sing softly in Doum’wielle’s ear, and the sounds were shocking.

Because they were gentle and melodious.

It was still dark outside when Doum’wielle woke up, but a small candle burned not far away, offering some light. She was warm under the thick fur, and alone.

Almost alone, she realized as she struggled to sit up, for the exit to the small dome structure was blocked by one of the pets, a short but thick wolf, or not a wolf, she realized as she leaned forward, but more like a huge badger, but one with too many legs, four on each side! Its thick fur glistened golden in the candlelight, but all Doum’wielle could really see were its long and pointy fangs, bared at her.

Doum’wielle fell back and the badger creature did likewise, curling into a ball, its middle two legs on one side scratching at its thick fur.

She tried to make sense of it all. Where was she? What had happened to her? Feeling strange, she looked down and kicked the fur off her bare legs, then shuddered to see that her feet were black and swollen, but smudged with some white lotion she did not recognize.

It was on her hands, too, and she rubbed them together, then smelled them. Her fingers were also blackened, but like her feet, they didn’t hurt. What was this stuff? What was this place?

She looked around for her clothes, but did not find them. She did, however, see a bowl set beside her bedroll, filled with some mushy substance. Keeping one eye on the fierce and strange badger creature, she picked up the bowl and noted a wooden spoon beside it. An aroma filled her nostrils, a bit pungent and quite fishy, but not off-putting.

Doum’wielle didn’t know if this was for her, or if it was food at all, but she wasn’t waiting for permission. She scooped up the spoon and shoveled the food into her mouth, only to wince in pain as the large spoon stretched her cracked and broken lips. She tossed the implement down and lifted the bowl like a wide cup, licking at it, swiping her fingers across the bottom and then sticking them in her mouth to get every drop. In that effort, she tasted, too, the lotion on her hand, and it felt wonderful against her lips.

A healing balm?

“Won abo, a bik tiknik tu gahta bo,” she heard from the entryway, and she snapped her head around to see the larger orc, the male, crawling into the dome.

Doum’wielle spoke a bit of Orcish, but she hadn’t a clue what this one was saying to her. She stared at him for just a moment, before realizing that the blanket had fallen, revealing most of her naked torso. She gathered up the covering defensively and set her glare on the orc, silently vowing to fight it to the death if it came at her.

But that didn’t happen. The orc smiled and nodded, and averted his gaze, then held up a bundle, nodded again, and tossed it to her lap.

Her clothes.

He went out and the eight-legged guard followed. Doum’wielle grabbed up her clothing, pausing only in surprise that it was so warm. She moved quickly to dress herself, then fumbled about her breeches and realized that the orcs had apparently discovered and taken the small knife she carried in her pocket. All she had were those breeches, her undersmock, and her shirt.

No overcoat or cloak or hose or shoes.

She heard talking outside and the female orc crawled in. She began speaking gruffly and pointing to Doum’wielle’s feet, and when the elf paused to try to decipher any of it, the orc grabbed her ankle and tugged her left leg out straight.

Doum’wielle kicked at her with her right foot, retracted it, and moved to kick again, but held her leg cocked when the orc brought up her left hand, lifting a very thick spear, with a very long white and decorated tip, up before Doum’wielle’s face.

“Meenago foto fo!” the orc snapped at her. Behind her, the hulking male entered the dome.

Doum’wielle let her leg sink back down to the floor. She winced as the female inspected her foot, roughly rolling the leg from side to side. Nodding, apparently satisfied, she then placed the foot down on some smaller furs she had carried in, and began gently but tightly wrapping it.

The male tossed Doum’wielle a pair of large mittens and motioned for her to put them on.

She put on the left, but then motioned her right hand to the empty bowl and tapped the same hand against her lips.

The orcs both shook their heads. “Tu gahta bo,” the male said.

Disappointed, Doum’wielle put on the other mitten.

The female orc finished wrapping both feet, tying the furs tightly in place, then nodded to her partner, who dropped down and grabbed Doum’wielle by the ankles.

“What?” she cried. “No!” She tried to wriggle free, but hadn’t a chance against those powerful grips. She struggled to roll over, but again, the orc held her feet steady—while his partner tied her legs together with a heavy cord.

“No!” Doum’wielle demanded again. She grabbed the bowl and threw it at them to little effect. She fell back and tried to bring forth a spell, tried to shake off the mittens so that she could make the proper movements.

But then she was sliding, being hauled through the short tunnel and out into the cold, cold dark.

Before she could even make sense of it, the female orc was beside her, hoisting her upright and wrapping her in the fur blanket upon which she had slept—upon which they all had slept, Doum’wielle only then remembered. She shuddered and gasped as it occurred to her what they might have done to her . . .

No, she realized. They hadn’t hurt her at all in any way. They had just come in and slept against her. Kept her warm. Healed her feet and hands.

It made no sense.

Too confused to sort it out or even begin to think of any spells, too weak to have any hope of fighting back, the elf had no choice but to let whatever might happen, happen. Wrapped tight, she couldn’t begin to resist anyway as the large male hoisted her up in his arms and carried her for a bit before plopping her down on a small sled. She was sitting up, her back against the vertical back of the carriage, and a large rope went over her, the orc binding her tightly in place.

His partner came over and placed hot stones all around her, then dropped other items, including Doum’wielle’s pack, which now appeared stuffed, on the front length of the low sled, securing them. The male returned, leading four of those badger-wolf creatures tethered together, and soon, tethered to the front of the sled.

He walked back around Doum’wielle and she could feel his weight when he stood upon the back of the sled, right behind her.

His companion rushed past her then, startling her, driving her own sled and a similar scrabbling team.

“Hike!” the male shouted, startling her once more, and away they went, sprinting across the snowy and icy plain.

Hours passed.

They stopped and rested, throwing large chunks of blubbery meat to the eight strange badger-wolves, or whatever they were.

Formidable was what they were, Doum’wielle quickly understood as the pack went at the meat, shredding it with ease, ripping it apart with one tear in what seemed like hardly an effort.

The female orc kneeled beside Doum’wielle, bowl in hand, and began giving her small bites of the fishy mush, while the male inspected and tightened her bindings.

It occurred to Doum’wielle that they weren’t keeping her alive so much as fattening her up. She wasn’t about to refuse the food, though.

Off they went again, rushing across the snowpack and coming to another small dome of snow. They didn’t strip her down that night—her clothes weren’t wet, she understood—but they did share the blankets, all three, and they did keep her legs tied, and they did keep one of their pets at Doum’wielle’s feet.

While she thought about escaping the two orcs, Doum’wielle wasn’t about to do anything to spark the ire of that fearsome and powerful beast.

It was still dark when she fell asleep, and still dark when she woke up, when they ate again, when they put her back on the sled and started off once more.

Eternal sunshine, and now eternal darkness.

Doum’wielle knew that she was lost, that her mind was gone, at least in regard to the passing of time. This was the night that wouldn’t come for what seemed like many tendays, and now . . . it wouldn’t leave.

They repeated the cycle over and over, moving to more domes set in a line. The mountains loomed much closer now—or was it even a mountain before her? The silhouette against the night sky was level, though high. After the fifth rest—or maybe it was the sixth; Doum’wielle couldn’t be sure—they started off again, but pulled to an abrupt stop soon after. The two orcs moved between the sleds, right beside her, jabbering at each other, and again, Doum’wielle couldn’t make out a word of it.

She got the feeling, however, that they had sensed something or someone out there.

The female orc lit a candle, which seemed like quite a stupid thing to do.

The male took it from her and held it up high above his head, which seemed stupider still.

She understood, though, as a group of humanoids approached. Allies, clearly, for the female orc rushed out to meet them and converse with them.

Doum’wielle couldn’t quite make out who or what they might be. They weren’t built with the sturdy frame of an orc, but were lithe, elf-like. But too thin for this freezing weather, she thought. Were they even wearing clothes?

The male orc began untying her from the sled as a pair of the newcomers approached. Yes, they were dressed, Doum’wielle saw, but in a weird, dark, thin material, a single piece of clothing, booted and gloved and with a coif as one might see on a suit of fine chain mail, and with a full face mask as well.

Red eyes peeked out from the slit in one, glowing amber orbs from the other.

They looked at each other and shrugged, then nodded and drew out handcrossbows, bringing them up as the orc unwrapped Doum’wielle from the blanket.

“No, no!” she cried, realizing her fate. She tried to turn and pull away, getting so far as to plant one foot and try to leap off the sled. Then she heard a pair of clicks, and felt the burn as two quarrels burrowed into her.

“Why?” she asked, turning back to the two slender newcomers.

The strength left her legs and she fell back upon the sled. She felt the cold wind, but then it seemed to go away.

All of her senses receded.

Doum’wielle fell in on herself.

Why won’t the sun come up? she wondered, her last thought on the frozen plane.

Part 1

Finding Purpose

My little Brie.

For most of my life, I have been blessed with friends and with a sense of, and clear direction of, purpose. I see the world around me and all I ever hoped to do was leave it a bit smoother in my wake than the choppy waters through which I traveled. I gained strength in the hope of some future community, and then indeed, in that community when at long last I found it. Found it, and now embrace it as my world expands wonderfully.

It’s been a good life. Not one without tragedy, not one without pain, but one with direction, even if so many times that perceived road seemed as if it would lead to an ethereal goal, a tantalizing ring of glittering diamonds so close and yet just outside of my extended grasp. But yes, a good life, even if so many times I looked at the world around me and had to consciously strive to ward off despair, for dark clouds so often sweep across the sky above me, the murky fields about me, and the fears within me.

I weathered change—poorly and nearly to self-destruction—when my friends were lost to me, and never were the clouds, the fields, or my thoughts darker. During that midnight period of my life, I lost my purpose because I lost my hope.

But I found it again in the end, or what I thought the end, even before the twists of fate or the whims of a goddess manifested my hope in the return of my lost friends. I might have died alone with Guenhwyvar on that dark night atop Kelvin’s Cairn.

So be it. I would have died contented because I was once more true to that which I demanded I be, and was satisfied that I had indeed calmed many waters in my long and winding current.

But then there came more, so unexpectedly. A return of companions, of love and of friendship, of bonds that had been forged through long years of walking side by side into the darkness and into the sunlight.

And now, more still.

My little Brie.

When I burst through that door to first glimpse her, when I saw her there, so tiny, in the midst of my dearest friends, in the midst of those who had taught me and comforted me and walked with me, so many emotions poured through my heart. I thought of the sacrifice of Brother Afafrenfere—never will I forget what he did for me.

Never, too, did I expect that I would understand why he did it, but the moment I passed that threshold and saw my little Brie, it all came clear to me.

I was overwhelmed—by joy, of course, and by the promise of what might be. More than that, however, I was overwhelmed by a sense I did not expect. Not to this degree. For the first time in my life, I knew that I could be truly destroyed. In that room, looking at my child, the product of a love true and lasting, I was, most of all, vulnerable.

Yet I cannot let that feeling change my course.

I cannot hide from my responsibilities to that which I believe—nay, quite the opposite!

For my little Brie, for other children I might have, for their children, for any children Regis and Donnola might have, for the heirs of King Bruenor, and Wulfgar, and for all who need calmer waters, I will continue to walk forward, with purpose.

It is a good life.

That is my choice.

Fly away on swift winds, clouds of darkness!

Take root, green grass, and blanket the murky fields!

Be gone from my thoughts, doubts and fears!

It is a good life because that is my choice, and it is a better life because I will stride with purpose and determination and without fear to calm the turbulent waters.

—Drizzt Do’Urden

Chapter 1

Stirring the Pain

The Year of the Star Walker’s Return

Dalereckoning 1490

He sensed the cold, just the cold, like a tomb of ice tightly wrapped about him, squeezing and freezing. He felt her fear, her lament, frozen it seemed, like the physical world about her, as if she was stuck and held in the moment of her death.

Kimmuriel gripped the feline-shaped hilt of the weapon tighter, physically trying to strengthen the telepathic connection.

Startled by the returned image, the same image, the same sensation of simple cessation of . . . everything, the drow fell back a trio of steps, then looked at the blade for just a moment before placing it down on the table before him.

“You seem shaken,” came an unexpected voice across the small and dimly lit chamber. Kimmuriel glanced over to see his host, Gromph Baenre, the archmage of Luskan’s Hosttower of the Arcane. “I am not quite used to such a sight as that.”

“I do not fully grasp the enchantment on this weapon,” Kimmuriel explained.

“It is a minor dweomer in the grand scheme of Mystra’s Weave and Lolth’s Web, surely,” Gromph answered. “The sword seeks bloodletting, and will manipulate its wielder to that end.”

Kimmuriel was shaking his head through the explanation. “It is more than that,” he answered. “It is . . . pride. This enchanted sword, above all, wishes to be the instrument of the greatest wielder.”

“For more blood.”

“I think it more than that.”

“And this quibble has Kimmuriel Oblodra, who dines with illithids—what do they eat, after all? And how do they eat it?” Gromph paused and shuddered as if his train of thought had been derailed by the image he had conjured in his mind. “You dine with illithids and are flummoxed by a mere sentient weapon? I could more greatly enchant a dozen such blades within a month, if that will keep you so entranced and pleased.”

“It is not Khazid’hea,” Kimmuriel explained. “It is the connection to those the sword has truly dominated.”

Gromph’s flippant expression changed at that explanation and he walked over.

“It senses Catti-brie,” Kimmuriel explained. “When I am holding it, and when I force myself into it, I can feel that which she is feeling. Or perhaps it is what she was once feeling. I cannot be sure.”

“Now, that could be interesting,” Gromph said with a wicked smile, and Kimmuriel glared at him. “She is human, and so weak,” Gromph needled against that disparaging stare.

“Not just Catti-brie,” Kimmuriel said. “Another, too. Elven and drow.”

Gromph arched an eyebrow.

“Doum’wielle Armgo,” Kimmuriel explained.

“Not that wretched creature,” the archmage replied with a heavy sigh. “She lives?” He snorted and sighed again, shaking his head.

“If you had wanted her dead, why did you merely banish her? Why didn’t you just do it yourself, then and there?”

“Because that would not have been painful enough.”

“Your anger seems misplaced.” Kimmuriel reached for Khazid’hea again, lifting it before his eyes. “I believe she was more victim than perpetrator in whatever it was that elicits such rage from you.”

“She was half elf and half drow,” Gromph dryly replied. “That is sin enough.”

Kimmuriel shrugged and let it go. Gromph was making some progress these last months in Luskan. He was beginning to see the wider picture here, with a civil war quietly simmering throughout Menzoberranzan as his sisters and House Baenre did battle with much of the city, aided by a force now being called the Blaspheme: nearly eight hundred resurrected drow, returned to their previous forms after centuries of servitude in the Abyss as horrid driders. Menzoberranzan was on the verge of a war for its heart and soul, and it appeared that the devotees of Lolth were in a losing position, though the fight would likely last years if not decades.

“She lives, though?” Gromph asked, taking Kimmuriel from his thoughts.

“I don’t know,” Kimmuriel answered after considering it for a few moments. “So it would seem, unless these are the final memories of Doum’wielle somehow stored within Khazid’hea. Still, I do not believe that to be the case, so likely, yes, she lives.”

“Who else does this sword sense?”

“There are others, but they are faint. Perhaps they held the sword long ago, or it never gained such control over them as it clearly held over Catti-brie and Doum’wielle, or . . .”

“Or the others are dead now.”

Kimmuriel nodded. He understood that Khazid’hea was an old, old creation, and figured that it had likely been held by many hands over the centuries, and that it had surely dominated most of them. No, those who had been overcome by Khazid’hea and were now dead were not lurking here in the sensations of the sword.

Gromph gave a laugh.

“What is it?” Kimmuriel asked.

“Catti-brie,” the archmage explained. “The sword fully dominated Catti-brie.”

“That was long ago, when she was barely more than a girl.”

“I know,” said Gromph. “I find it humorous, of course, for now, were she to grasp that blade and Khazid’hea tried to dominate her, she would laugh it away. She would likely twist that sentience so far about itself that it would never unwind.”

“You just said she was human, and thus weak,” Kimmuriel reminded him, and he grinned at the cloud that passed across Gromph’s amber eyes. The truth of Catti-brie clearly pained the wizard. She was not supposed to be as powerful as she obviously was. She was human, just human, and yet she was no minor warrior, no minor priestess, and no minor wizard. Gromph hated admitting it—even to himself, it seemed—but he truly respected her.

“Where is the Armgo whelp, then?” Gromph asked, unsurprisingly shifting the conversation away from the source of his present consternation.

Kimmuriel shrugged. “I do not know. Only that it was bright, the sun shining on white snow. And cold . . . so very cold.”

“I threw her into the far north,” said Gromph. “That she has survived at all is surprising. Was that your thought when I entered?”

“She was terrified,” Kimmuriel said. “She was afraid and perhaps in the moment of death.”

“The north is full of large animals, I am told.” Gromph’s voice trailed off as Kimmuriel began to shake his head.

“She was not running from animals,” he explained.

Gromph stared at him curiously.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...