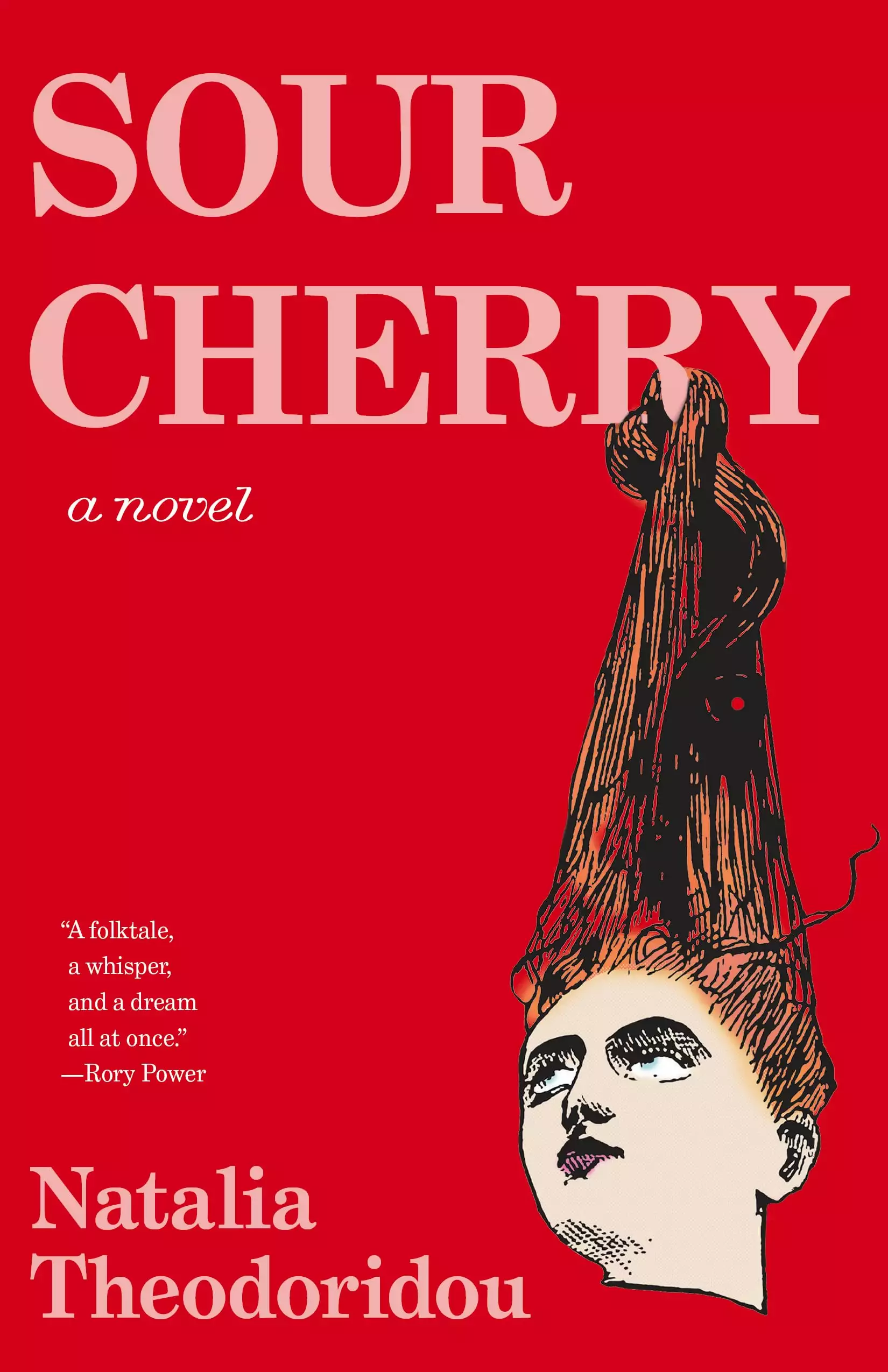

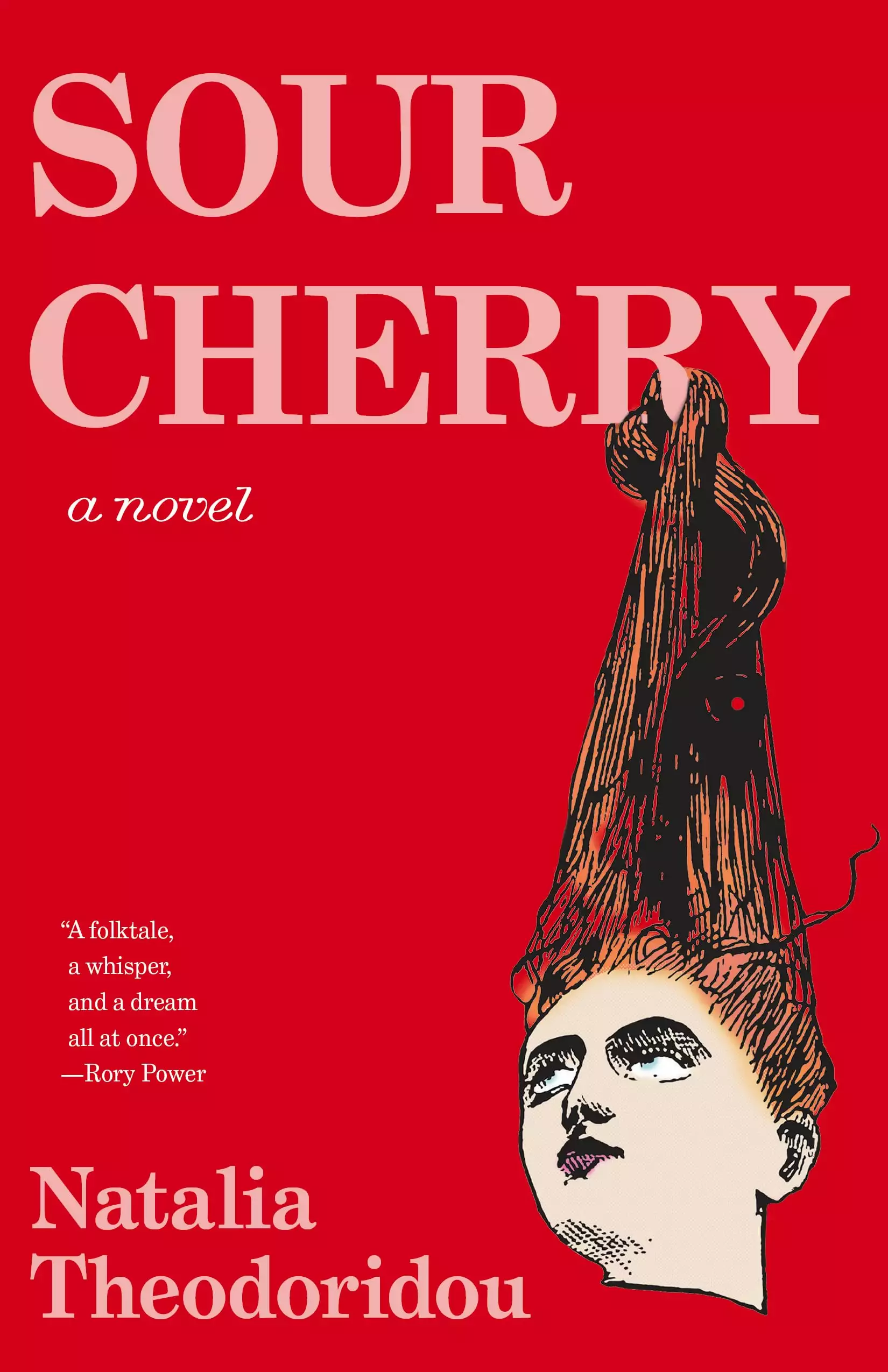

Sour Cherry

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

“A folktale, a whisper, and a dream all at once.”—Rory Power

“If you love Kelly Link, Angela Carter, and Carmen Maria Machado, then Natalia Theodoridou is your new favorite author.”—Benjamin Percy

A stunning reimagining of Bluebeard—one of the most mythologized serial killers—twisted into a modern tale of toxic masculinity, a feminist sermon, and a folktale for the twenty-first century.

The tale begins with Agnes. After losing her baby, Agnes is called to the great manor house to nurse the local lord's baby boy. But something is wrong with the child: his nails grow too fast, his skin smells of soil, and his eyes remind her of the dark forest. As he grows into a boy, then into man, a plague seems to follow him everywhere. Trees wither at the roots, fruits rot on their branches, and the town turns against him. The man takes a wife, who bears him a son. But tragedy strikes in cycles and his family is forced to consider their own malignancy—until wife after wife, death after death, plague after plague, every woman he touches becomes a ghost. The ghosts become a chorus, and they call urgently to our narrator as she tries to explain, in our very real world, exactly what has happened to her. The ghosts can all agree on one thing, an inescapable truth about this man, this powerful lord who has loved them and led them each to ruin: If you leave, you die. But if you die, you stay.

Natalia Theodoridou's haunting and unforgettable debut novel, Sour Cherry, confronts age-old systems of gender and power, long-held excuses made for bad men, and the complicated reasons we stay captive to the monsters we love.

Release date: April 1, 2025

Publisher: Tin House Books

Print pages: 307

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Sour Cherry

Natalia Theodoridou

(DAWN. THROUGH THE WINDOW, POOR LIGHT.)

This is a fairy tale.

The ghosts shift along the walls of our apartment. I correct myself: his apartment. Everything is in order, the way he wants it, the furniture luxurious but sparse, modernly eclectic: a sofa clad in green velour, the kind of wooden dining table you’d find in a monastery, a glass cabinet, this armchair. The walls are blue. For once, there is no wallpaper. The ghosts pull on the gauzy curtains instead, their mouths open and empty. This is a protest, I know. They don’t like it when I imply our stories are not true. So I try again.

This is a fairy tale, I say, but everything I’m about to tell you is also something that happened. In another time, another place.

Better?

The women look at their dresses, which used to be white, before they were red. They run their palms across their own bodies. Beads fall soundlessly to the floor.

But I’m not talking to them now. I’m talking to you.

Here is the key, I’ll give it to you: this is a fairy tale because I need the distance.

You fuss with my clothes, my hair, my skin. You worry over me, as if I’m not your mother and you’re not my child, our roles upended, permanently disturbed.

I’m fine, I tell you. Listen.

The clock on the wall with no wallpaper ticks forwards, and I try to remember how to tell time. My mind lags numb, numberless. I turn to the window for answers—what is time, after all, but an encounter with the passing of light? There isn’t much of it left. A day, perhaps: one dawn, one noon, one dusk. After our light runs out, people will come. They will open our doors. They will walk in, they will go looking, and they will find us. They will take you away, take me away too.

I glance at the closed bedroom door. The women in their frocks avert their eyes, palms before their spectral faces, No, no, don’t go there. Not yet.

This morning, after he fled with you calling after him, terrified and confused, you asked if he’s always been a monster. You ask it again, now. The light doesn’t wait, so I must tell you while there’s still time—while I can still speak, and you can still listen.

But how do I tell it? How do I talk about this?

The ghost women reach, arms outstretched, and I reach, too, for what I know, for what can grow, for things passed down skin to skin, mouth to mouth. Then the ghosts speak. Start again, they whisper. This is how you do it, see? You start with milk.

So I say: This is a fairy tale.

It begins with a wet nurse. With Agnes, at the beginning, or close enough. This is how I imagine it, and her, not-quite-mother and not-quite-wife, the first discarded woman.

The wet nurse

They hired Agnes to nurse the child without asking for references. It should have given her pause—in the village, you lived and died by the opinion of others; without your neighbours’ good word, you were nothing. But she saw the mother from afar, when she came down to the village with a servant, looking for help: the shadowed eyes, clavicles knifing her dress. How could Agnes say no? Besides, she had milk; what was she supposed to do with it? Let it go to waste, let the child starve? She wasn’t a monster. And is there anything more enjoyable in life than being needed?

She said yes.

She had thought she’d walk to the manor house; she didn’t have much to carry, only a bundle of clothes and her good Sunday shoes, a golden necklace given to her by her mother before her passing a few months ago, the chain so thin it felt like thread, and a book she couldn’t read, with a castle painted prettily on its cover.

She had spent the entire night imagining her journey to the house: how she’d walk across the village carrying her bundle, her breasts heavy, her shoes muddy from the road, the villagers eyeing her silently and crossing themselves. How she’d go up the hill along the brambled road only carriages ever took, to haul things for the residents or ferry them to the town when the mistress felt lonely or the master had business to attend to. Agnes wasn’t sure what kind of business it was, and she never asked.

“They say you don’t see the mistress, but you hear her,” a woman had said to Agnes at the market, not long ago. “They say there’s something wrong about her, and the house is overrun with rats and worse things, and you’d do well to stay away from it.”

Still, Agnes had said yes. So she’d walk all the way up that hill despite the burn in her calves and the stitch in her side, and then she would pause by the black iron gates to catch her breath and take in the house, the exquisite sight of it, equal parts unnerving and breathtaking. She’d linger there awhile. The high arched windows with their tinted panes would shine in the sunlight like a crown. There might be people behind those windows, looking at her, thinking about what a long way she’d come, waiting for her to walk up the path and rattle the bell to be let in.

But they sent a carriage. It was waiting for her when she stepped out of her father’s house ready to face the village, the road, this new life. The driver flicked her an appraising gaze. It lingered a moment too long, making her shiver in her shawl. Then the horse snorted its impatience and the driver turned away. She climbed in, and off they went.

There was no need to pause at the gates, either. The carriage rolled through unceremoniously and delivered her to the front door. The road was cobblestone, flanked by statues of lions and stags and animals she didn’t recognise, their paws gripping the ground, their faces mournful with mouths hanging open. When the horse stopped, the driver didn’t open the door for her, but the carriage remained still long enough for her to determine she should get out.

It was the cook who greeted her at the door. A short woman, too thin for a cook, with flushed cheeks and tight grey curls that escaped from her cap. “The mistress is not feeling well,” Cook said. “She’s sorry she couldn’t welcome you herself.”

Agnes extended her free hand to grasp Cook’s and also curtsied a little. “I’m Agnes,” she said. Though the information seemed unnecessary, the meeting felt unfinished without it.

Cook gave her a lopsided smile. “Sure you are,” she said. “Come with me.”

The place smelled of dust. Few people worked for the couple, and far fewer than were required to keep such a massive house clean, warm, and not falling apart. Later, she’d hear the stories about servants falling ill, waking with bruised knees they couldn’t explain, and field hands quitting after nightmares no prayer would keep away.

Agnes would hear all the stories, she’d tell a few herself, and maybe she would even believe a couple were true. But for the moment, she was taken

with the high ceilings, the echoing rooms, the animals stuffed and mounted on every wall. Cook led her through the corridors, her shoes tapping on the dull marble of the floor. There were paintings too—strange ones, by Agnes’s estimation, though she didn’t have much experience in art, only the one painting that hung in her father’s house. It’d been payment for the family’s single horse, given to a stranger—a beautiful young man who passed through the village. He’d made a good case for himself, moved her father to tears over how much he needed that horse. But he had no money, and instead offered to paint a picture for Agnes’s father—“an original,” he’d called it. Her mother thought her husband was crazy to agree, as did everyone else who heard about the offer; is it any wonder that people in the village thought her family was odd? But he did agree, and so the stranger sat in the middle of their kitchen and created a painting just for them. Agnes watched the whole process from start to finish; for the two days it took to complete the painting, the stranger didn’t sleep, and neither did Agnes. She saw the mountains take form, the trees come to life, the quiet stream running down the middle of the canvas, bisecting it—and the perspective was off enough for that stream to seem as if it were pouring from somewhere high up, perhaps even the sky. By the time the stranger was done, she could have described every detail of the painting with her eyes closed. Not that anyone ever asked her to.

These paintings, though, were nothing like that. No quiet bucolic scenes, no faint blue mountains in the distance; they were dark, sinister, the creatures in them barely human. There was a woman with a rosebush for hair, holding an apple and gazing at the viewer with not a hint of emotion, and a curly-haired man with an enormous mouth and tiny hands, sitting on a sleeping horse, and a creature that sent chills down Agnes’s spine, not because of some such fantastical detail but because its eyes were far too human, the face familiar.

Finally they reached her room. It was small and plain, cold like the rest of the house, but Agnes found it cosy. She immediately liked the tall window that overlooked the grounds and the woods beyond—there were fields on the other side of the house, but she couldn’t see those—and the creaking of the floorboards reminded her of her father’s house. There was even a dresser and a mirror, and her bed seemed not too soft but not too hard either. It was perfect.

After Cook left her alone, Agnes unpacked her things, hung up her dress, put the book on the dresser, and hid the necklace in a handkerchief stuffed into her good shoes. Then she padded through the house on her own, marvelling at the strange paintings and the imposing columns that held up the ceilings. When she got tired, she went back to her room and opened the window to let in the breeze. It was a good view: the woods, the pretty garden that sprouted from the grounds. And then, out of the corner of her eye, a flash of something white, moving between the trees. She was leaning farther out the window to get a better look when she heard the baby cry. It was a terrible sound. A desperate, lonely sound.

Agnes would always remember the first time she saw the child. It was later that same night, hours after her arrival at the house—“the castle,” she’d already dubbed it in her mind. The mistress appeared only for a moment to greet her and hand her the swathed, squirming creature. The woman was in her nightgown, her eyes sunken, with bruised half-moons hanging underneath them. The baby screamed, inconsolable, so Agnes took it, and the mistress disappeared as soon as the bundle left her arms. Agnes wouldn’t see her again for days, but thought of the mistress escaped her mind in that moment because all her attention was on the baby now. His red face, his eyes so full of rage. If his tiny fists hadn’t been tucked inside his swaddle, he’d have clawed her eyes out.

She sat in the nearest armchair with him in her lap. Cook was there, too, observing, overseeing—but Agnes barely registered her presence. She freed her breast from her blouse and cradled the child’s head, her arms sure, undisturbed by his squirming and his screams. She didn’t think of her own baby then, his cold body, his blue face, the little lord’s milk sibling. Instead, she leaned back on the chair and stared at the room, the animals crawling on the walls, the dust on the windowsills, the strange paintings, the floor. And then, the baby was quiet. She fit his angry little mouth like they were made for each other.

“What was the child’s name?” you ask, and I pause.

Does it matter? I wonder. Sometimes you become a character in someone else’s story and so lose your name. Sometimes, you give it up willingly. Because a name can also be a burden, a legacy and a responsibility. A curse, even—and he, for now, is only a child. So I will not give him a name. For as long as I can help it.

They were inseparable after that. Agnes would feed the baby until he fell asleep, then take him to her room and place him on her bed. She’d cover him with a scratchy wool blanket she’d crocheted herself and sit by his side to watch him sleep. At night she’d often wake up with a start, certain the little lord would be blue in the face, that there’d be a night terror sitting on his chest, suffocating him, but she only ever found him fast asleep in the same position she’d left him in. When he cried, she’d pick him up and soothe him, and when that didn’t work, she’d place him on her lap and tell him the stories her mother had told her when she herself was a child—some of which I’ve heard myself: stories of princes who did great violence to save their princesses, stories of women who suffered terrible trials to save their men. Sometimes, the men in them had wings, the women ursine ears. Often, the princes and queens had eyes the colour of the sea—but Agnes changed that and made it so their eyes were the colour of the woods, because she had never seen the sea. What else were fairy tales for, after all, if not for showing you the world as it is and helping you survive it? And sometimes, Agnes made up her own stories, some of which she’d crafted in her mind months and months ago, thinking she’d get

to tell them to her own baby. Others she concocted on the spot, inspired by the paintings in the house: about lambs that could speak, about mothers with urns for hearts, and about birds whose eggs, if eaten, would hatch inside your body and teach you the language of the winds.

Life for Agnes took on that watchful quality it tends to do around small children, the hours no longer narrated by roosters and mealtimes and clocks but by the needs of the little lord.

She didn’t call the child anything, and when he learned to talk, he didn’t call her anything either. Together they existed, a knowing between them that went beyond names.

Agnes went back to the village once a month to see her father. Her old home seemed smaller every time she visited, as if her stay at the house diminished everything else in her life, like a distorting mirror. And each time, though it would be years before she admitted this to herself, she was glad to be back in its dusty halls, to be enveloped by its musty smell, stared down by its dark walls.

She only met Lord Malcolm weeks after she started working for him. She had just returned from her first visit home. The baby was asleep in her arms, and Agnes was heading upstairs to her room when she saw a tall, thin figure standing in front of the great fireplace in the sitting room. He wore a set of keys around his waist. She took him for the groundskeeper or one of the servants, so plain were his clothes.

Agnes watched from the doorway. At first, she thought he was crying—it was the faltering way his back shook beneath the light fabric of his shirt. But as she stood there, she realised she’d been wrong: the man was laughing at the fire. It made the keys rattle.

“Why are you doing that?” she asked.

The man turned to face her. She recognised him from the painting with the sleeping horse, though both his mouth and his hands looked normal in person. This man was no groundskeeper. His hair was curly and the same black as the child’s, so dark that when it caught the light just right, it took on the most beautiful blue tint. The lips, too, resembled his son’s. Thick and perfectly shaped.

“Doing what?” he asked back, his voice too deep for his frame.

“Looking at the fire like that,” Agnes replied, now suddenly embarrassed by her own insolence.

But the man seemed intrigued by her directness. “Because it’s beautiful,” he said.

“Because I’m in awe that a thing this powerful can be contained so. It’s man’s greatest achievement. Don’t you think?”

Agnes thought that was the most ridiculous thing she’d ever heard—besides, she’d lit the fire before leaving for the village, and she was no man.

She said so.

Instead of getting angry, the man burst out laughing. A full-throated laugh, coming from deep in the belly.

“Hush,” Agnes whispered, but it was too late. The baby had already woken up and begun to cry. “Look what you did,” she said.

The man looked at Agnes and smiled. He said, “Look what you made me do.”

The child’s nails grew too fast. Agnes cut them every morning, but at night again they dug into her breasts, carved tiny crescents into the skin of her forearms. He was always hungry, his teeth sharp like needles. All babies have sharp teeth, she knew, but not like this. Once, the child bit her so hard she had to check her flesh in the mirror twice, certain he’d torn away a piece of her. But she didn’t mind. When the baby nursed, Agnes’s head emptied of everything else, of the world and everyone in it. There was only this child.

She understood that his need to be loved was great, and so Agnes loved him greatly. If anyone had asked whether she’d have changed anything—as I’m told people did, later, after everything—she’d have said no. She wouldn’t change a thing.

The mother was a spectre. Agnes glimpsed her white nightgown turning a corner or fleeing up the stairs. The few times she had a chance to look at the woman’s face, Agnes thought her beautiful, despite the wan skin, the downturned lips. Even on the occasions when the master invited Agnes to dine with him, claiming he enjoyed their conversations, the mother joined them only for a few minutes, and she didn’t eat at all.

Tonight was one of those times. Outside, it was still light, a fresh spring evening, but in the dining room the air smelled stale, heavy with the scent of game cooked in red wine—venison, Agnes thought, shot and bled by the master himself. She’d just taken a sip of wine when the woman entered the room. The drink burned the roof of Agnes’s mouth, made her gums grow numb, coated her teeth with a sour film.

The woman was still in her nightgown, her hair loose and greasy. “I’m late,” she said, but her husband waved her words away.

“You can never be late, my love,” he said. “Agnes was keeping me company.”

She turned to Agnes, alert for a moment, and Agnes felt as though she’d been caught stealing. Blood rushed to her cheeks. She couldn’t meet the woman’s gaze, so she looked down at her hands instead.

The moment was gone quickly, the alertness too. The mother sat down, elbows on the table, one hand supporting her head, lips sealed tight. She stared at her food, and she stared at the child, and at the woman who cared for it, and at her husband, who didn’t speak another word.

When his wife left, the master leaned back in his chair and his shoulders fell; in disappointment, yes, but also, Agnes thought, with relief.

A few moments passed quietly, the little lord’s calm breathing the only sound in the room.

“What’s wrong with her?” Agnes asked, in the direct way she’d come to understand the master appreciated.

He remained silent for a long time. Agnes thought she’d been mistaken, that he was angry at the bluntness of her question. But when the man stood and approached, it wasn’t to punish her or send her back to her room. Instead, he touched her shoulder gently so she would stand, and led her to the window overlooking the garden, the stone fence, the cultivated land beyond.

The man’s body felt large next to her. He smelled of wine and straw. She wanted to touch his beard but didn’t.

“What do you see?” the man asked.

She looked; the garden was fierce and green, with tangled brambles and flowers that didn’t keep to their beds. The stone fence sported moss—dead yellow and grey. The field was green too, dotted with red. So much red.

“Poppies,” she said.

The master nodded, smiled.

“The land turns corpses into flowers.”

When the child was weaned, he could already walk on two strong feet, pull at the weeds in the garden with two strong arms and pluck them from the earth’s fist. Agnes imagined she’d be dismissed now that her milk was no longer needed, but nobody told her to leave. She could choose to leave herself. To go back to—what? What was there for her in the village? Not even a stranger who came, who loved her for a night, who painted, who left. Not even a blue-lipped baby to call her own.

So she stayed. Let her milk run dry. Gradually she understood she was to be the child’s minder, though nobody told her as much. Besides, the mother seemed so helpless around the child, and he was so attached to Agnes by now—did she really have any choice in the matter? It seemed natural that she would stay.

They slept in the same bed often, the boy curled up against her, seeming both softer and more angular than Agnes expected his body to be, his fingers grasping her arm so tightly her flesh bruised. He smelled darkly of the forest; not the clean scent of trees but the musky tang of their insides.

The child grew and his face remained as lovely as it had always been—though sometimes, when she looked into his eyes, Agnes saw a shadow there, a hard thing her stories said might nestle in the eyes of a monster. But she was only a girl from a village. What did she know of monsters?

She oversaw the boy as he played in the field, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...