Chamberlain Smeg, Charlie to his few friends, unfolded the Edmonton Journal in a ritual as familiar as putting on socks. He leaned his ample frame forward on his elbows and peered through drugstore reading glasses at the print that faded with each passing year. He longed for the time when newspapers hadn’t cheaped out on ink. The headlines reported the same news as every day that week but he was compelled to read on. It wasn’t the need to stay up-to-date to engage in water cooler chat; he was never one for that, and now with the job behind him, the only water cooler he saw was attached to his fridge. Paul Galloway, his twenty-two-year-old stepson, stood rooted in front of it, his legs unnaturally wide apart like he needed to scare off a large animal. Paul opened and closed the fridge door multiple times, either because he also needed glasses or was hoping for a different result; maybe some leftover sausages or an egg he didn’t have to fry himself.

The furnace moaned, trying to reach the temperature Paul had jacked the thermostat up to. Charlie had a right to say something about the heat as the guy who paid the bills, but would have to wait until the earbuds were removed from Paul’s ears. Charlie set his glasses down on the table as Paul grabbed a four-litre plastic jug of milk, poured liberally over his Honey Nut Cheerios and over the side of the bowl onto the counter. What was still in the jug made it back into the fridge for once. Paul padded across the room on bare feet, his sports shorts hung low over his hips, the only nod to winter a heavy black hoodie with a PlayStation logo on the front.

The house, typical of the period homes in the neighbourhood, had a large kitchen, the kind meant for boisterous chatter, filled with the hominess of bread baking and mounds of potatoes being peeled. It spoke to a time when children built snow forts, careened down hills on toboggans, and moved out when they turned eighteen. In Charlie’s day, becoming an adult was a rite of passage, an accomplishment, a chance to show what you were made of. After scraping a chair over the tile floor, Paul landed the bowl of cereal safely on the table and sat down. Some days, Charlie wondered what Paul was made of. The young man pulled one earbud from its nest and croaked a good morning. His face lit up to reveal tiny crow’s feet around his eyes. Charlie caught a glimpse of the boy he used to take to the park.

back in.

Paul’s head bobbed up and down vigorously, his black hair sweeping his face like the back end of a street cleaning truck. “I wanna catch a podcast on writing a novel.”

Charlie choked on his coffee, although by now he shouldn’t be surprised at the whims of his stepson. He peered at him over the large blue and grey clay bowl in the middle of the vintage table, which housed two blackened bananas and a wrinkled apple. Both the bowl and the table were additions Nancy added to the room. The bowl had always been filled with fresh fruit—oranges, grapefruits, kiwi—in colours that changed like the northern lights. The boys knew they were expected to eat it. The table abutted the kitchen window, which faced north into a snow-filled backyard shaded from the sun that crept slowly above the horizon. Light found its way through the stained glass of the front door, splashing up the hardwood floors to display an array of paint samples over the wall that needed restoration. In fact, the entire kitchen had been neglected since Nancy died.

Charlie reached for his forgotten peanut butter toast and took a bite. He slurped it down with coffee, this time with more success. “You’re writing a novel?”

“Yeah, I can express myself so much better in writing, you know? Like when I write an email, I can get all my thoughts down way better than when I’m talking. I’m just not a gifted talker like you.” He shovelled in two heaping spoonfuls of Cheerios in quick succession.

Charlie didn’t consider himself a gifted speaker, maybe because he lacked interest in communicating with people. Paul, on the other hand, was loquacious, and a mouthful of cereal didn’t usually stop him. It was Charlie’s assumption that he was talking about games when he chattered on about dark fantasy worlds and romantic landscapes; it seemed unlikely the boy had an imagination. But still, the content of his soliloquies could be the stuff of stories.

“I suspect there’s a lot more to writing fiction.” Charlie wasn’t keen on encouraging this latest distraction of Paul’s.

“I didn’t expect you to understand, but I’ve got to do something with my life,” Paul said, his chin pointed in Charlie’s direction.

Charlie didn’t appreciate hearing his own words parroted back to him. He’d meant a job with a paycheck. He glanced down at the sports section. The player grades from last night’s hockey game were dismal.

“What are you writing about?” he asked, without looking up.

“It’s not about, man. You write from within, your emotions, not looking down at it. No sage on the stage. That shit’s not gonna work.”

Charlie had no idea what response was expected from him. He lifted his gaze and stared at Paul, and tried to figure it out.

“Sorry. Likely never mentioned, I’ve been writing rap for quite some time now. Poetry, I guess you’d call it.”

der one roof, the farther apart they drifted. Charlie blamed himself. Nancy’s illness had consumed him; he wanted so much to ease her pain that he didn’t notice Paul’s. He had managed to connect with the twelve-year-old who walked into his life, but reconnecting with the teenager was a whole different thing, and the man sitting in front of him was still a riddle. Now he wondered about the emails Paul had started to send him—mostly musings about dinner. Charlie thought it likely Paul didn’t want to get off the couch in the basement and walk upstairs to have a conversation. But maybe there was more to it.

“Can I read your poems?” he asked and hoped that the answer would be no. Then he’d have to respond intelligently.

Paul tipped his bowl and drained the remaining milk. “Sure, but I don’t know if you’ll get it. I could give you some books to read to give you a sense of the genre, you know, like Tupac?”

“Isn’t rap associated with violence and the glorification of criminal lifestyles? I’m not sure you have the experience to write authentically about it.” Paul had grown physically into a man, but emotionally, he wasn’t much beyond that boy Charlie used to guide through the Toys R Us parking lot. Street smart, he was not.

“That’s a stereotype. You should learn more about it before you criticize.”

“Okay,” Charlie said, knowing it was going to be a stretch for him to meet his stepson where he was at. Wherever that was.

“Anyway, I have to go. My podcast is starting.” He dropped the bowl in the sink.

“Pretty sure you can listen to those any time.” Charlie opted to ignore the bowl that hadn’t been put in the dishwasher.

“They’re posted at set times. This one just came out,” he said, and stuck his earbud back in place. “I want to get started on my book.” His receding footsteps echoed the still bouncing bowl.

Charlie, book in hand, was engulfed in the mission to track the murderous Kelso brothers when he was pulled off course by the chime of his wired doorbell, one of the original features of the house. He’d consciously not updated it, as opposed to not getting around to replacing. He cherished the early twentieth-century brick house with its low-pitched roof, dormer windows, and large front veranda, much like he did his grandmother, who had raised him in it. As the visitor was likely to be someone looking for money, perched expectantly on the wide front steps, he lowered his head and continued reading. The bell rang again, imploring him to set down his worn copy of Guy Vanderhaeghe’s The Last Crossing and glance out the front window. Meaghan Byatt’s little economy car was parked neatly against the banked snow. He’d often considered the possibilities of reverse wiring the doorbell to give out shocks, like an electric fence. Worked to keep horses away.

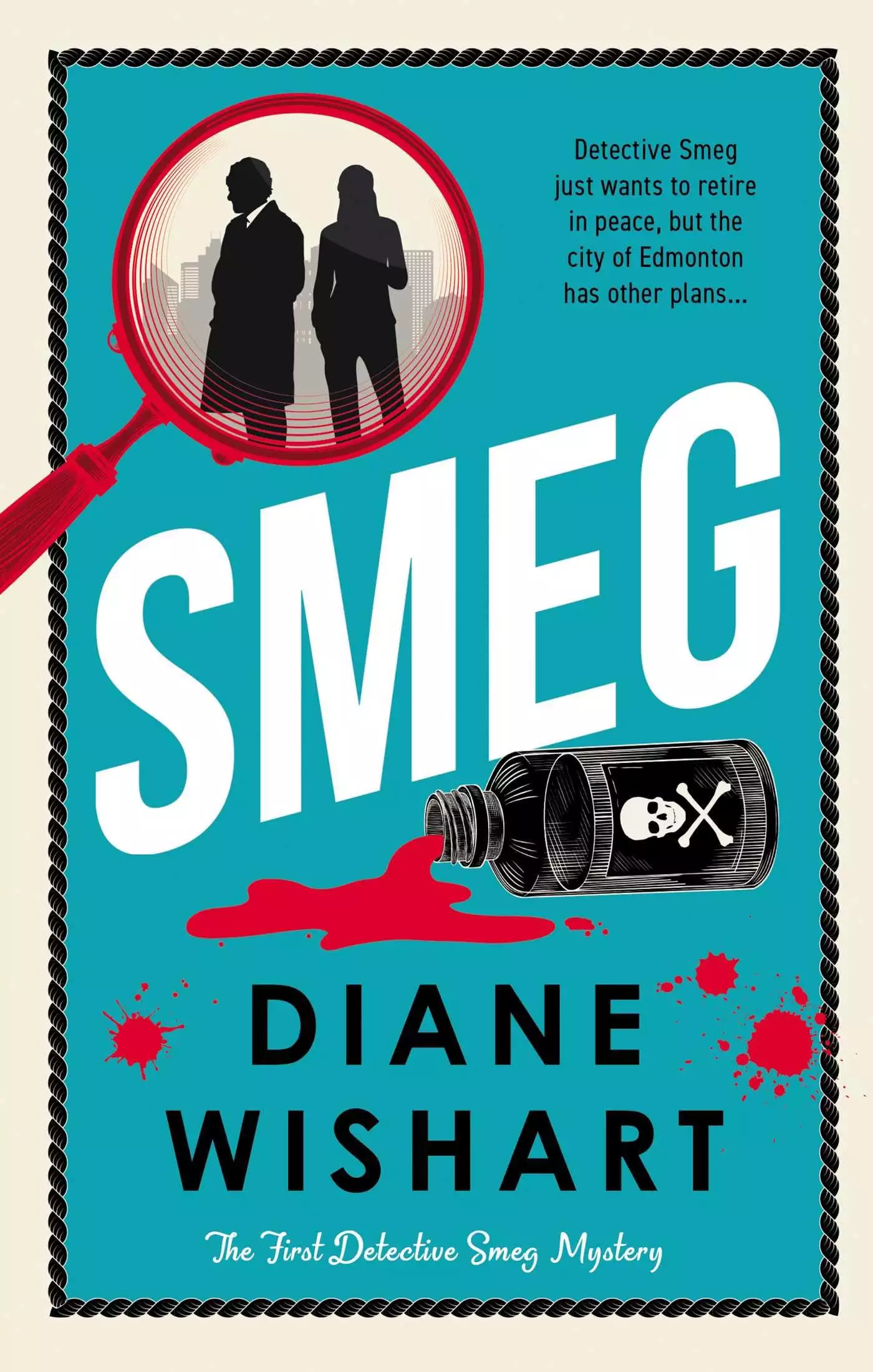

Detective Byatt, a former partner for mere days. Kid in big girl clothes. She was a star over in robbery, and top brass had wanted to profile

her, so they transferred her to the prestigious homicide unit. She was the youngest detective by far in homicide. Clever, dedicated, and attractive in an unconscious way. She looked impressive on a recruitment poster. He wondered if her virtuous looks were helping her solve crimes. Maybe that was unfair. After all, it wasn’t her fault he’d packed it in.

Charlie heaved himself up from the high-backed mahogany chair and ambled to the door. She waited eagerly on the verandah, snowdrops highlighting long ginger hair that framed her confident face.

“Hey, Detective Smeg. Just checking in, wondering how you’re doing.” A pause suggested it was his move.

He didn’t take it. People checking in, asking how he was doing, were beginning to piss him off. He’d retired, not lost a limb.

“I’m sorry. Did I wake you?” Her furrowed brow mirrored his own.

Smeg tried to remember when he’d last combed his hair. “No,” he said. “Not a problem.”

“I’ve been digging around in this case we were working on.” Her hand moved toward the file folder tucked under her arm. “Got a few minutes to chat?”

It was unusual, this re-engagement. Smeg had watched, over the course of his forty years with the force, a disappearance of sorts when officers retired. He often thought someone should investigate. The same fate might have been his but for the fact that he’d been invisible for years. Obsolete, out of date. He was an old-style cop, dedicated to his craft, principled, hard-working. He watched younger,

less experienced officers advance past him. That was fine, as he didn’t want the desk job; the paperwork and bullshit grew exponentially the higher one rose in the organization. He could also live without the disdain that emanated from those who thought rank transcended skill and experience.

Byatt’s hand dropped, leaving the file folder in its place.

Smeg breathed in the not-unpleasant fresh air and made no move to close the door. “Don’t you have a new partner?”

“Oh god, where to start. Some sort of glitch with the paperwork is the short answer.” Byatt’s heavy parka, undone and wet with melted snow, seemed too much for the warm December day.

Paperwork? Since when did they put that much thought into it? In Smeg’s experience, these matchups were made of convenience, like the way he and Byatt had been thrown together. His former partner was out on long-term disability, replaced by the next person in the door, as if a stellar career could be wiped out with one bullet to the leg.

He sighed. “Sure, what can I do for you?”

“Can I come in?”

Smeg stepped back, took and hung up her coat, then ushered her into the living room.

“I love this room.” Her smile reinforced her words as her eyes took in each detail.

He knew she saw a living room filled with laughter. Its rose-patterned wallpaper grew out from under the chair rail and wainscoting Nancy had painted a soft Chantilly lace, an invitation to sit awhile. The ceiling and floor moldings had been replaced with less fussy versions of the originals that moved the eye toward the

arched doorway. At least that was what Nancy told him. These days, his eye tended toward the floor-to-ceiling bookshelf with books stuffed in on top of each other.

“Do you play the piano?” Byatt asked, acknowledging the shiny black upright in the corner with a tilt of her head.

“No, that was my wife’s.”

She’d been gone five years. Cancer. He’d only had her with him for the same number. Byatt didn’t know that, but he wasn’t going to fill her in. Nancy had always pulled the drapes open in the early morning, fluffed the throw pillows, and polished the piano until it resembled the plate glass window. She was a concert pianist who gave the room heart and light. He couldn’t bear to part with the piano. Nancy had taught Paul to play, but Charlie knew he didn’t need to keep the piano for him. Paul’s talent hadn’t been sparked.

“Please,” he said, and indicated she should sit on the loveseat. He took his place back on the still-warm chair.

“This case,” Byatt said and leaned forward. “Human tissue found in a bathtub drain?”

Byatt’s sandy sweater and dark jeans played to the room, and Smeg found himself relaxing. She, on the other hand, had bright pink spots on her cheeks and breathed a little too rapidly. They hadn’t had much time together before he left. She was a good kid. Although at thirty-five, she wasn’t really a kid. If he’d had the energy, he could have worked with her, but after he’d failed his former partner, leaving her alone in an alley while he chugged along trying to keep up, he couldn’t bring himself to get involved again.

been found?”

She leaned back and draped one arm over the back of the loveseat. “Two boys playing pond hockey found a decomposed body in a frozen-over swamp west of the city. Shot the puck into the reeds and hit him on the head. The lab tests have confirmed it’s the same person. I have some thoughts I’d like to bounce off you.”

He tilted his head, a little wary. If the department had valued his expertise, he might not have put in his papers. So, what did Byatt want with him now? He’d left her high and dry and little hurt, he knew. But he couldn’t explain, not to her. Really, not to anyone, although the department therapist had tried to get him to talk when he’d gone for mandatory counselling after the incident. It was the end of the road for him for a number of reasons: out of sync, out of style, and out of shape. The opposite of Byatt, who oozed confidence and great physical conditioning, and who he realized was talking. Something about a contract killing. He pulled himself back to her case for the details: shot in a back alley, the body bleached in a bathtub before it was moved, no DNA evidence on the body. There were ties to organized crime. The accused lived alone in the apartment where the body was cleaned so he was the prime suspect. But with organized crime, there would of course have been others involved, especially to move the body.

“You’ve got a case with strong circumstantial evidence, given the human tissue match. Does the accused have known gang affiliates?” Smeg leaned forward.

“He’s a member of the West Side Gang, and he’s known to police.”

“Have the victim’s personal effects been located?” Smeg forgot he didn’t give a damn about this case.

“A search of the dumpster behind his apartment revealed nothing, but a wallet, wrapped in a plastic grocery bag, was found in a dumpster one block over. We’re checking for a match on the prints.” She seemed to be getting on well on her own, figuring it out.

“What are you struggling with?”

“Someone else has confessed. I told Staff Sergeant Singer I thought the confession was false. The person, however, knows details that haven’t been in the paper.”

“Is there enough factual basis for the plea?”

“Singer and I talked about our mutual distrust of reliance on confessions. She agrees we need to find out the motive behind the confession.”

“Coercion by gang members?”

“Singer isn’t convinced. I just love her leadership, you know? We have an impressive success rate in homicide, and much of it is because of her. Anyway, I have an interview set up with the confessor for tomorrow.”

Smeg’s stomach was beginning to remind him of why he’d quit. Byatt had quickly learned how to get into Singer’s good books by drawing her in, making her feel like a mentor. Smeg had been an actual mentor to his former partner, but the fresh-faced climber in front of him was a new breed of cop.

“Where’s the gang unit in all this?”

sure that it was a contract killing and that it was ordered by the West End Gang, it’s ours.”

“Sounds like that determination can be made. Don’t you think Gangs would have some useful intel?”

“Singer’s okay with our approach at this point. Sometimes the Gang Unit messes things up, you know?”

In Semg’s experience, the cock-ups usually came when individuals got territorial.

“Well, if you don’t need anything more from me, I’ll get back to my day.” He pushed himself forward in his chair. It was time to get back to the things that mattered, like removing stressors from his living room.

A shadow crossed Byatt’s face. “If the confession doesn’t work out, I’m going to need a partner to help pursue other leads.”

“Maybe they’ll have assigned someone to you by then. These arrangements don’t usually take very long.”

Byatt stared, seemingly unable to process what he’d said. “Singer’s the one who wanted me to talk to you. I don’t care if you help out or not.” In the dim light, Smeg was unsure if he’d imagined the little pout of her lower lip.

“Sorry,” Smeg said. “I’m done with all that.” Although, he did wonder what Singer was thinking. She used to be one of the good ones.

A blur of black hair flew by the open living room doorway.

“You have a dog?”

“No, a stepson.”

Byatt turned her attention back toward Smeg as she rose to her feet. “Anyway, I was supposed to leave the file with you. Do whatever you want with it.” She glanced toward the fireplace and headed to the door. Smeg followed.

As she stepped into the hallway, she ran right into the speeding stepson coming back the other way with a bag of chips and a Coke in hand.

Charlie reached out a protective hand to keep her from falling backward. “Paul, watch where you’re going.” He rubbed the top of his nose where a headache was forming.

“Sorry,” Paul mumbled and looked at the floor.

“No problem. I’m Meaghan.” She extended her hand. “You’re late for something?”

Paul took it. “Always in a hurry. I was thinking about my writing and not paying attention.”

“Cool. What are you writing?”

As they exuded the virtues of modern poetry, Charlie briefly saw another world he didn’t belong in, a world that was young, bright, and opened up like the blooms of a Christmas cactus. They moved on to a television show and its subtexts of race and gender, both enamoured of its in-depth writing of complex themes and accurate representation of the times. Even television had left Charlie behind.

At the door, Charlie thanked her for stopping by.

“Stay in touch,” he heard himself say.

Returning to his chair, he noticed a long, ginger hair curled up on the love seat, which he promptly disposed of. Stay in touch indeed. ...