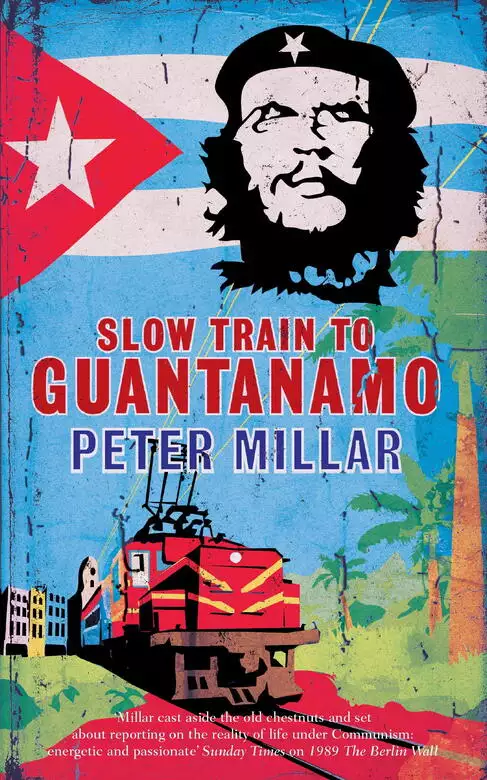

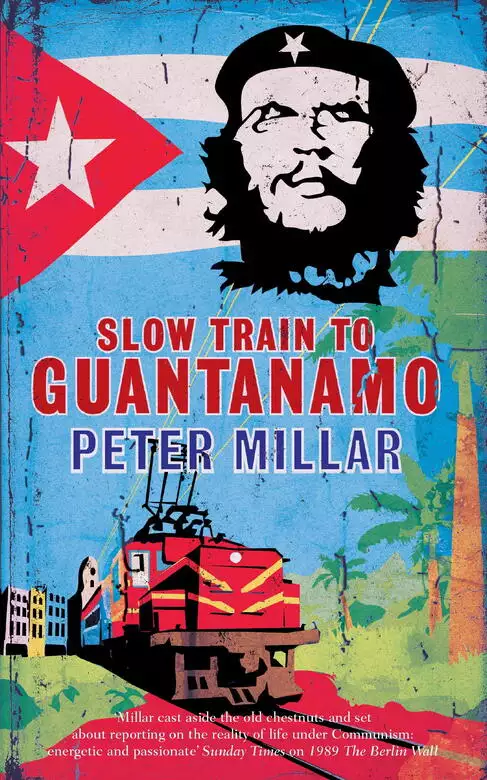

Slow Train to Guantanamo

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Starting in the ramshackle but romantic capital of Havana, Peter Millar travels with ordinary Cubans, sharing anecdotes, life stories and political opinions to the far end of the island, the Guantanamo naval base and detention camp.

Release date: July 1, 2013

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 272

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Slow Train to Guantanamo

Peter Millar

Slow Train to Guantanamo

‘The book gives an insight into Cuban daily life, Caribbean communism, the food, the beer, the colours, the smells (good and bad) and the realities of an artificial economy that the package deal tourists will never even glimpse. If you have ever been to Varadero and Havana (the standard package), read this book, then go back and see the real Cuba whilst you still can. If you have never been to Cuba, read this book, and if you then don’t want to go to Cuba, you have no soul, and they wouldn’t want you there anyway. Go to Cuba, but take your own toilet seat, and paper, the locals will understand’ – J. P. Hayward

1989 The Berlin Wall

‘The best read is the irreverent and engaging account by Peter Millar, who writes for the Sunday Times among other papers. Fastidious readers who expect reporters to be a mere lens on events will be shocked at the amount of personal detail, including the sexual antics and drinking habits of his colleagues in what now seems a Juvenalian age of dissolute British journalism. He mentions his long-suffering wife and children rather too often, but the result is full of insights and on occasion delightfully funny. The author has a knack for befriending interesting people and tracking down important ones. He weaves their words with his clear-eyed reporting of events into a compelling narrative about the end of the cruel but bungling East German regime’ – Economist

‘The most entertaining read is Peter Millar’s 1989 The Berlin Wall: My Part in its Downfall, a witty, wry, elegiac account of his time as a Reuters and Sunday Times correspondent in Berlin throughout most of the 1980s’ – Spectator

‘1989 The Berlin Wall is part autobiography, part history primer and part Fleet Street gossip column … Millar cast aside the old chestnuts and set about reporting on the reality of life under communism. In bare Stalinist apartments, at hollow party events and over cool glasses of Volker the gravedigger-cum-hippie, the Stasi seductress “Helga the Honeypot”, Kurtl the accordion player whose father had been killed at Stalingrad, and the petty smuggler Manne who has been separated from his parents by the Wall … Energetic and passionate …’ – Sunday Times

All Gone To Look for America

‘Succeeds in capturing the wonder of America that the iron horse made accessible to the world’ – The Times

‘Witty yet observant … this book smells of train travel and will appeal to wanderlusts as well as armchair train buffs’ – Time Out

‘Fills a hole for those who love trains, microbrewery beer and the promise of big skies and wide-open spaces’ – Daily Telegraph

The Black Madonna

‘With a journalist’s keen eye and ear, and a born storyteller’s soul, author Millar has written a truly compelling, globetrotting thriller. Rich in history and cultural detail, The Black Madonna is a page-turner of a novel that flings us into the heart of the essential conflicts of our times. Look out, Dan Brown, make way for Millar’ – Jeffery Deaver

Stealing Thunder

‘An intelligent thriller … fast-paced and convincing’ – Robert Harris

It is nearly twenty-five years since all of a sudden communism keeled over and died. The annus mirabilis of 1989, when the Cold War caught its death, the Berlin Wall crumbled, the dominoes of the Soviet empire in Eastern Europe tumbled and in quick succession the Soviet Union itself disintegrated, seems a lifetime ago. So long, in fact, that it is hard to remember that back then it was widely considered that capitalism had won and was from now on invincible as a global economic and social system.

Five years after the great financial crash of 2008, that no longer seems such a wise conclusion.

Apart from the aberration of China’s adoption of a strange form of capitalist communism, only two states remained that genuinely considered themselves dedicated to the principles of Marx and Engels: North Korea and Cuba. Both were considered, particularly by the United States, little better than pariahs, with sanctions imposed against them.

The reality, of course, was always dramatically different. While North Korea was, by and large, a cold and barren half-peninsula, Cuba is one of the most beautiful, sun-blessed islands in the Caribbean. While the North Korean people were drummed into regimental parades and marched through the streets of Pyongyang, the Cuban people drummed, played and sang themselves into and out of the bars of Havana and onto the big screen. While North Korea’s leaders died and succeeded one another in dynastic fashion, Fidel Castro hung on, seemingly forever, until eventually, in 2008, in admittedly similar dynastic fashion he yielded power to his not much younger brother Raúl.

And now Cuba is changing. Raúl himself has said he will serve five more years at most. Cuba beyond the Castros is already on the horizon. What will it be like, and more to the point what is it like now, outside the luxury enclaves visited by most beach-loving foreign tourists, in the streets, buses and trains used by the ordinary people?

As someone who lived in East Germany, the Soviet Union and communist Poland and reported on life in those countries before the fall of the Iron Curtain1 and immediately afterwards, Cuba exerted a remarkable fascination. And as someone who has travelled the length and breadth of the United States by the method of transport that created that continental nation,2 it seemed to me there could be no better way to experience life in Cuba on the ground, literally, than by travelling the length of the island by train.

Cuba’s railway is – or was, as I was about to find out – one of the first and most extensive national systems in the world. Cubans had the fifth national railway system in the world, after the United Kingdom, United States, Germany and France, before Spain or most other European countries, and it remains the only truly national system in Latin America. Although just how extensive it was I had no idea.

This is not a guidebook, not a book about politics, nor even, I regret to tell railway buffs, a book about trains. It is a book that deals with all those topics and I hope a lot more. It is a book about people and places and country on the cusp of change. It is a book about travel and why it is the best education the world can offer. It is about life and living it, the Cuban way. And believe me, for all the deprivations the Cubans today still suffer, there are worse ways to live. Far worse. Ask anybody in Iraq or Afghanistan.

1. 1989: the Berlin Wall (My part in its Downfall), Arcadia Books 2009.

2. All Gone to Look for America, Arcadia Books 2008.

It is 4.10 a.m. on a dark, steamy tropical morning and raindrops that look and feel like drowned bluebottles are falling from the rusting corrugated iron of the station roof. I have just been poured out of a train the Cubans nickname El Spirituario – an experience as close to being below decks on a seventeenth-century slave trader as a middle-aged, middle-class European man ever wants to get.

I stumble down the station steps in search of transport to where I am hoping to find a bed for what remains of the night. The options are not great: a donkey-cart with a candle burning in a jam jar as its tail light, or an ancient Soviet Lada with only one door, no windows and a patchwork quilt of badly-stitched upholstery.

This is Santa Clara, capital of the cult of Cuba’s secular saint and martyr, the chess-playing, motorcycle-mad humanitarian medic and ruthless revolutionary who looked like a movie-star; his iconic image has stared from bedroom walls of generations of liberal students across the globe for more than half a century. It was here that Argentinian Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara won the battle – in reality little more than a train derailment and subsequent skirmish – that would give control of the Caribbean’s capitalist playground to the Communist Fidel Castro. The aftermath of the Battle of Santa Clara would make Che a household name in almost every nation on the planet.

And I hate to say it, Che, I really do, mentally addressing myself to the ghost that hovers over Santa Clara, but it looks like a crock of shit.

After four hours on an overcrowded train in 30ºC heat and 80 per cent humidity, with broken seats, no windows (thankfully), compartments with no doors and endlessly flickering fluorescent corridor lights, all I want to do is sleep. I decide to leave the candle-burning donkey-cart for another time and opt for the less rustic but possibly faster option, the one-doored Lada.

I had thought that maybe one reason communism still survived in Cuba might be the weather: it’s a lot easier being poor when the sun is shining, but now I’m not so sure.

Ten minutes after falling into the Lada, the rain is still beating a slow staccato on the roof and my sleep-starved brain has been addled by a ghetto blaster strapped to the passenger seat sun visor blaring at full blast as we rattle along otherwise empty and silent pre-dawn cobbled streets.

My driver is wearing rain- or sweat-soaked red shorts and torn orange T-shirt. He grins, gleefully unembarrassed by the high-volume salsa and farting Soviet exhaust pipe, as we scan the shuttered front doors behind ornate iron grilles in a street of low terraced whitewashed eighteenth-century Spanish colonial houses. One of these is the casa particular – a private home licensed to take in foreign guests, the Cuban equivalent of a B&B – where I have booked a room. But which one? The concept of giving houses numbers or even names, if ever common, has clearly fallen into disuse. But then as buying or selling homes has been banned for half a century, pretty much everybody knows who lives where.

I stare in bleary despair at the lack of identification when an elderly white-haired gentleman, roused to our presence by the cacophony on his doorstep, opens shuttered doors, then the elegant wrought iron-grille in front of it, and beckons me in.

The Lada driver pockets his fare and his ramshackle vehicle with under-inflated tyres, elaborate upholstery, and missing door rattles off into the predawn twilight, the tinny din from its improvised audio equipment mercifully vanishing with it as my host welcomes me into another world. Or perhaps as L. P. Hartley would have put it, another country: the past.

Beneath my feet is an ancient hardwood parquet floor, ahead of me two white Doric pillars flank the entrance to an open courtyard, like the interior of a Moroccan riad, with tall double doors ahead and to the right leading on into the interior of the house. Cuba’s current reality intrudes here only in the form of the green corrugated plastic that covers part of the courtyard, dripping steady separated streams of rainwater.

Those who owned only one property, their home, at the time of the 1959 revolution were allowed to keep it. For those with a home big enough – ironically the middle classes which, despite belonging to them, Castro most detested – it has become not just a roof over their head but a major means of support. Toleration of foreign tourism has provided an alternative economy with access to hard currency. The communist paradise of Castro today has a vital private sector on the side.

My elderly host grandly throws open the double doors on the right to reveal a room with high ceilings, a four-bladed fan and, most importantly of all, a wide welcoming double bed.

‘Buenas noches,’ he bids me with a smile, and I collapse onto a mattress as hard as Brighton beach but more than welcome.

That old Phil Collins anthem to the homeless is running through my head as I hit what passes for a pillow: ‘Oh, think twice, it’s just another day for you and me in paradise.’ I drift off into confused dreamland wondering just how the hell I got into this in the first place.

Just five days earlier I had arrived in the relative luxury of a Virgin Atlantic premium economy at Havana airport, where most foreign visitors make their first acquaintance with the curious reality of life in Cuba. For most of them – whooshed off in luxury air-conditioned coaches to coastal resorts all but hermetically sealed off from the rest of the island – their last. But it is still unmistakably Cuban. For a start the security checks are on the wrong side.

Most airports are worried about you taking bombs onto airplanes; the Cubans are worried you might be bringing bombs off one. After five minutes doing my level best to give an unwavering smile in response to the unwelcoming stare of an immigration official in the shortest skirt I have ever seen on an immigration official anywhere, the woman behind the glass window handed back my passport brusquely and gestured to the scanners ahead, and said: ‘Seguridad.’ Security.

Despite Ronald Reagan adding Cuba to the US State Department’s list of ‘state sponsors of terror’, Havana’s record on that score is actually better than Washington’s. The White House – or at least the CIA – was behind one proxy invasion of Cuba, more than eight attempts to kill its head of state, and almost certainly one bomb which brought down an aircraft (of which more later), killing all on board. And that is without even mentioning that the greatest number of people considered terrorists by Washington itself has for several years been held on the bit of Cuban soil US armed forces still squat on, at the far end of the island: the goal of my present odyssey, Guantánamo Bay.

The dark days belong to the distant past – most incidents were in early 1960s. But the Cuban authorities, perhaps more than ever given the advanced age of their leaders and a growing sense of fin de régime, are not taking any chances. Anyone entering the socialist paradise of Cuba is necessarily subject to scrutiny.

Which was why half an hour after landing, and five days before being decanted into Santa Clara in the bleak hours before dawn, I found myself standing in a queue of incoming passengers watching an immensely large lady from Santo Domingo dressed in what looked like a tent arguing loudly with a stern-faced customs official in an even shorter skirt than the immigration lady had worn.

The argument, improbably enough, was as to whether or not she should be allowed to bring six one-litre cans of banana milkshake mix unopened into the Socialist Republic of Cuba. ‘How do I know what’s in there?’ the customs lady was asking, clearly suspicious that it might be anything from gunpowder to cocaine. On an island where milk itself is usually only available on a state-issued ration card to certified mothers of small children, a large tin of powder claiming to contain banana milkshake mix is something regarded with deep suspicion.

There may be no flights or ferries to the United States (indeed US travel websites such as kayak.com or expedia.com won’t even give you information about flights to Cuba, as if the huge island on their doorstep wasn’t actually there). But from all over the rest of the Americas, flights pour into Havana daily, from Caracas, capital of Venezuela, which under the late – and in Cuba sorely lamented – Hugo Chavez, had become the country’s best friend, but also from Panama, from Lima, from Buenos Aires, from Santiago in Chile, from Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic, whence the lady in front of me was trying to import the banana milkshake.

A glance at the arrivals and departures board illustrates that if the United States thinks it has cut Cuba off from the world – despite Barack Obama’s softer line, the punitive embargo remains in force, and citizens of non-Cuban ethnicity are banned from visiting – it is sorely deluding itself. Cubans see themselves as part of a much broader, largely Latin American world.

They refuse to use the word Americano for the citizens of the big country to the north of them, preferring instead the cumbersome Estados-Unidosenses (roughly: United-Statesians). They see themselves as Americanos, like most of the other passengers arriving at or transiting through Havana airport.

That did not, however, make for much obvious tolerance for the large lady from Santo Domingo. I never did discover if she managed to import her curious cargo. She was taken aside into a separate room – possibly to be strip-searched for any other curiously flavoured corrupting capitalist comestibles – just as I was beckoned forward. To my relief my little backpack of bare necessities was rubber stamped through and I passed into the steamy, tropical, complicated chaos that is the gateway to what is probably the most magical, quixotic, complicated and confused island in the world.

Havana airport, like a lot of other things in Cuba, bears the name of José Martí, a nineteenth-century poet and idealist, revered almost as much as Che, even if he was decidedly less successful. Unlike the Argentinian revolutionary, José Martí’s first glimpse of action was also his last. Aged just forty-two – three years older than Che when he was executed in the Bolivian jungle by CIA-sponsored government troops – Martí led Cuban rebels into battle against their Spanish colonial masters, heroically, romantically (and extremely stupidly) dressed in his trademark black suit, on the back of a white horse. He was immediately shot dead by a sniper.

This is one of those apocryphal but true stories that tells you a lot about Cuba. Martí was a Cuban nationalist who had a love–hate relationship with the United States, a socialist who was also a dandy, a charismatic romantic revolutionary, a poet and a nutcase. Today he is an airport.

Having sailed through immigration and security, my one moment of stress before heading for downtown Havana, was tipping the clutch of toilet ladies gathered purposefully round the door to the gents. I had 45 British pence in small change, which seemed an adequate sum though I doubted they would recognize the currency. They didn’t, but all that mattered was that it was foreign. Converted into the money nearly all Cubans are paid in, that is about as much as the average worker might earn in a day. In Cuba’s curious economy, the foreign currency tips alone make being a toilet cleaner at Havana airport a much sought-after profession.

Taxi drivers make more, a lot more, especially, as everywhere in the world, taxi drivers based at the airport. A ride into central Havana in what turned out by ordinary Cuban standards the height of luxury – a ten-year-old Peugeot 306 – was going to cost me, the cab driver grinned, 25 US dollars. At least, that was what he said. It wasn’t actually what he meant. In Cuba, money, like everything else, is complicated.

Prior to Castro’s revolution the Cuban peso was pegged to the US dollar, afterwards it was pegged to the Soviet rouble. When the USSR collapsed in 1990, the Cuban peso went into freefall, but in the bleak years after the collapse of the Soviet Union when even the Spartan supplies from the rest of the communist world dried up, the only option was to use the currency of the hated enemy. Cubans duly dragged out piles of dollars sent from relatives in the US and hidden under mattresses and for half a dozen years the dolar became the only money worth having.

Then, in 2004, George W. Bush decided he would do his bit to win the vote of anti-communist Cuban exiles in Miami and increased sanctions against Havana. In an admirable (if rash) fit of pique, Fidel responded by banning the use of the dollar. Its place was taken by the ‘convertible peso’ (already in circulation but not so widely used as the greenback). Ever since that has been the currency of necessity for foreigners and desire for Cubans. It is pegged to the US dollar, which means there are 25 ordinary (or nacional) pesos to every one convertible peso. The former are officially designated CUP (but universally simply called ‘pesos’) while the latter are designated CUCs, and usually called that too, phonetically pronounced ‘kooks’.

It sounds complicated, and it is, but it can be literally a matter of life and death in Cuba. There is not a whole lot you can buy with CUPs. Most bars in Havana and shops selling a limited variety of goods you get anywhere in most other countries deal only in CUCs, which means no ordinary Cuban can afford them. A doctor earns 500 national pesos a month – the equivalent of roughly US $20 (less than my cab fare). As the US-Americans say, ‘go figure’.

The important thing is not to get the two confused. If you do, despite the intrinsic honesty of most Cubans, it’s not hard to get taken for a mug, or to use a word that in the vernacular is almost equally insulting: a gringo.

On the way into the city my cab driver tells a caller on his mobile phone – the latest Cuban must-have but subject to interesting restrictions – to ring back because he has a gringo in his cab. To his surprise I immediately object. My Spanish is not great but nor is it non-existent and I resent being referred to by what I have always considered to be the contemptuous term for a US-American.

The driver looks abashed for about half a millisecond then shrugs, and says no, it’s not just Yankees, it’s, ‘You know …’ and then dries up. I suddenly realize he is struggling to avoid racial stereotypes. Eventually by a mix of body language, gestures and euphemisms he conveys his meaning: a gringo is any pale-skinned northern European-looking bloke. It is the only form of, albeit mild, racism I am to perceive in my whole Cuban adventure.

He admits to being surprised I understood. Most gringos, I gather, don’t speak much Spanish. Most of the pale-skinned northern European-looking blokes he meets come from Canada, so-called snow geese fleeing the winter. They too are, however, allowed to be called Americanos, which must make Cuba about the only place in the world where Canadians (if they understood) might take it as a compliment.

This got us talking enough for him to point out – if only to save his embarrassment by changing the subject – that the black BMW hurtling past us on the inside belongs to the South African ambassador. He knows this because Cuban number plates have a colour code. Black is for diplomats, with a number to signal their country, white is for government ministers, red for the tourist industry including hire cars, brown for the armed forces, green for agriculture, blue for all other state-owned vehicles (which in a communist country accounts for a huge proportion), and yellow for private vehicles, which by the bizarre logic of Cuba’s economy makes yellow the rarest colour.

So how is Cuba these days, I ask him, meaning, without spelling it out, post-Fidel, a world that as yet most Cubans are not quite sure has really arrived? I’m not really expecting an answer other than ‘wonderful as ever’, the sort of North Korean-style ‘dear leader’ reply that was common among the few Cubans who would talk to foreigners a decade or so ago. Since the man who was the Cuban revolution stood down from power in 2008 in favour of his younger brother, there have been some reforms and rumours of reforms. Change is afoot in Cuba, even if it is not exactly generational change: Raúl turns eighty-two in 2013 and Big Brother, heading for ninety, is still watching.

My driver’s answer, though not exactly critical, surprises me: ‘Better.’ Better? I ask in astonishment. Better under Raúl than under the sainted Fidel? In what way? ‘There are big changes,’ he offers voluntarily. ‘Now it is okay to do business.’ Isn’t that just the tiniest bit capitalist, I hint, using the dreaded ‘c’ word. He shrugs, thinks a second and gives me one of those gems of wisdom that on the right day cab drivers the world over are capable of producing: ‘Greed is not good, but making money is never bad.’

Then he drops me at the corner of Plaza Vieja, and with a broad smile pockets his 25 . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...