- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

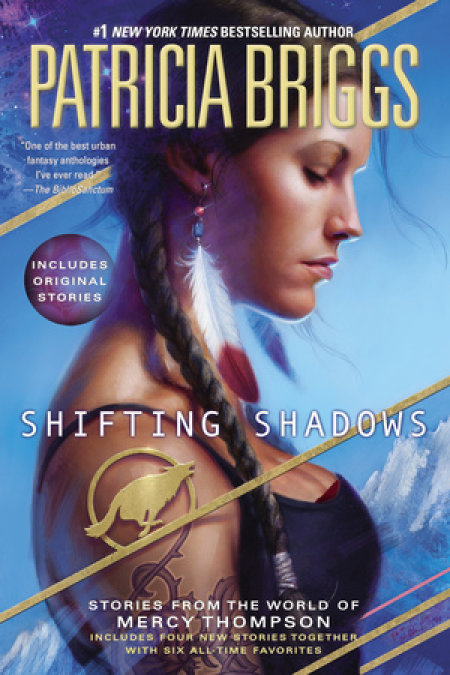

From the #1 New York Times bestselling author-including four all-new, original stories from the world of Mercy Thompson.

Mercy Thompson's world just got a whole lot bigger…

A collection of all-new and previously published short stories featuring Mercy Thompson, "one of the best heroines in the urban fantasy genre today" (Fiction Vixen Book Reviews), and the characters she calls friends…

Includes the new stories…

"Silver"

"Roses in Winter"

"Redemption"

"Hollow"

…and fan favorites

"Fairy Gifts"

"Gray"

"Alpha and Omega"

"Seeing Eye"

"The Star of David"

"In Red, with Pearls"

Release date: September 2, 2014

Publisher: Ace

Print pages: 464

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Shifting Shadows

Patricia Briggs

Herein is the ill-fated romance between Ariana and Samuel, the first half of the story that continues in Silver Borne. This is also an origin story of sorts, because how he met Ariana is also tied up with the story of the witch, his grandmother, who held Samuel and his father for such a long time. I have to say that if it had not been for the constant requests for this story, I, usually a teller of happier tales, would have left this one alone.

As a historical note—and for those who need to know how old Samuel and Bran are—Christianity came to Wales very early, perhaps as early as the first or second century with the Romans. When exactly the events of this novella took place, neither Samuel nor Bran could tell me. Bran just smiled like a boy without cares—so I knew it hurt him to remember—and said, “We didn’t pay attention to time that way. Not then.” Samuel told me, “When you get just so old, those first days blur together.” I am not a werewolf, but I can, after all this time, tell when Samuel is lying to me.

I do know that the events in this story happen a long, long time before Moon Called.

ONE

Three weeks to the day after I buried my youngest child, and several days after I buried my oldest—a young woman who would never become older—someone knocked at my door.

I rolled off my sleeping mat to my feet but made no move to answer the knock. It was pitch-dark outside, and the only reason anyone knocked at my door in the middle of the night was because someone was ill. All of my knowledge of herb lore and healing had not been able to save my wife or my children. If someone was ill, they were better off without me.

“I can hear you,” said my da’s voice gruffly. “Let me in.”

Another day, before the death of my family, I would have been surprised. It had been a long time since I’d heard my father’s voice. But my da, he’d always known when I was in trouble. That insight had outlasted my childhood.

I was beyond caring about anything, expected or unexpected. Being used to doing what he asked, I opened the door and stepped back.

The man standing outside entered quickly, careful not to lose the heat of the evening’s fire. The hearth in the center of my home was banked and covered for the night, and I wouldn’t fuel it again until the morning. With the door shut, the room was too dark to see because the window openings were also covered against the cold night air.

I did not see how he did it because there was no sound of striking flint, but he lit the tallow candle. He had always kept a candle on the ledge, just inside the door, where one of the rocks that formed the walls of the house stuck out. After he had gone and left the hut to me, I found it practical to leave one there as well.

In that dim but useful light, he pulled down the hood of his tattered cloak, and I saw his lined face, which looked older and more weather-beaten than when I’d last seen him, a dozen or more seasons ago.

His hair was threaded through with hoary gray, and his beard was an unfamiliar snow-white. He moved with a limp that he hadn’t had the last time I’d seen him, but other than that he looked good for an old man. He set down the big pack he carried on his back and the leather bag that held his pipes. He shrugged off his outerwear and hung it up beside the door where my da had always hung such things.

“The crows told me that you needed me,” he said to my silence.

He seldom spoke of uncanny things, my da, and only to the family—which was down to just me, as my younger brother had died four years ago of a wasting sickness. But Da was better at predicting things and knowing things than the hedge witch who held sway in our village. He also had an easier time lighting fires or candles than any other person I knew, wet wood, poor tinder, or untrimmed wick—it didn’t matter to him.

“I don’t know how you can help,” I told him, my voice harsh from lack of use. “They are all dead. My wife, my children.”

He looked down, and I knew that it wasn’t news to him, that the crows—or whatever magic had spoken to him—had told him about their deaths.

“Well, then,” he said, “it was time for me to come.” He looked up and met my eyes, and I could see the worry in his face. “Though I thought that I ran ahead of trouble, not behind.”

The words should have sent a chill down my spine, but I foolishly believed that the worst thing that could happen to me already had.

“How long are you staying?” I asked.

He tilted his head as if he heard something that I did not. “For the winter,” he told me at last, and I tried not to feel relief that I would not be alone. I tried not to feel anything but grief. My family deserved my grief—and I, who had failed to save them, did not deserve to feel relief.

• • •

It was a harsh winter, as if nature herself mourned with me. My da, he didn’t get in the way of my grieving, but he did make sure I got up every morning and did the things that were needful to get through the day. He didn’t push, just watched me until I did the right thing. A man worked, and he tended those things that needed tending—I knew those lessons from my childhood. He wasn’t a man people gainsaid, and that was as true of me as it was the rest of the village.

People came by to greet him. Some of the attention was because he’d been respected and liked, but more was because he could be coaxed to play for them. Music wasn’t uncommon in our village, most folk sang and played a little drum or pipe. But most folk didn’t sing like my da. When my mother died, no one had been surprised when he’d taken back to traveling, singing for his room and board, as he’d been doing when he first met her.

People brought him a little of whatever they had to pay for his music, and between that and the medicine I traded in barter, we had enough for winter stores even though I hadn’t put things back as I usually did. I hadn’t been worried about whether there was enough food to eat or enough wood to burn.

I hadn’t worried about myself because I’d have as soon joined my little family in their cold graves. With my da here, that route now smacked of cowardice—and if I forgot that sometimes, my da’s cool gaze reminded me.

It felt odd, though, not to have someone to take care of; for so long I had been the head of the family. I was not in the habit of worrying about my da: he wasn’t the kind of person who needed anyone to fuss over him. He’d survived his childhood—not that he’d spoken of it to me beyond that it had been rough. But my ma, she’d known whatever it had been, and it had sparked fierce pride tinged with sorrow and tenderness. I knew only that he’d left his home while still a stripling boy. He had traveled and thrived in a world hostile to strangers.

He was tough, and it gave him confidence that had backed down my ma’s folk when they objected to her marrying a man from outside the village. He was smart—and more than that, he was wise. When he spoke on village matters, which he didn’t do often, the villagers listened to him.

He’d survived traveling the world after my mother’s death—and he was still lit with the joy that made my home warmer than the logs on the hearth, though the chill left by the death of my little ones and their ma was deep.

My da, he could survive anything, and his example forced me to do the same. Even when I didn’t want to.

TWO

On the shortest night of the year, when the full moon hung in the sky, my grandmother came to us. I’d returned to my duties as village healer, so I didn’t even think of not answering a knock in the dead of night. Da had gotten used to the middle-of-the-night summonses that were the lot of a healer. He didn’t stir, though I was certain he was awake.

I opened the door to a stranger. She was a wild-looking young woman with hair that flowed in unkempt, tangled tresses all the way to the back of her knees. Her face was uncanny and so beautiful that I didn’t pay much heed to the beast that crouched beside her, huge though he was.

“The son,” she said to me. The magic flows strongly in you. Her voice echoed in my head.

“No,” said my da, who had exploded to his feet the moment I opened the door. He stepped between us. “You will not have him.”

“You shouldn’t have run away,” she told him. “But I forgive you because you brought a gift with you.”

“I will never willingly serve you, Mother,” my da said in a voice I’d never heard from him before. “I told you we are done.”

“You speak as though I would give you a choice,” she said. She glanced down, and the beast I had taken for a dog lunged at my da.

I grabbed the cudgel I kept beside the door, but the beast was faster than I was. It had time to bury its fangs in my da’s gut and jerk him between us. The only reason I didn’t brain Da was because I dropped the cudgel midswing. And after that, there was no chance to fight.

• • •

She turned us into monsters—werewolves—though I didn’t hear that term for many years. She bound us to her service with witchcraft and more cruelly through her ability to break into our minds—in this she had more trouble with Da than with the rest of her wolves. Though she looked like a young woman to all of my senses, I think she was centuries old when she came knocking on my door.

The first transformation from human to werewolf is harsh under the best of circumstances. I now know that most people attacked brutally enough to be Changed die. The witch had some way to interfere, to hold her victims to life until they became the beasts she desired. Even so, I would have died if my da had not anchored me. I heard his voice in my head, cool and demanding, and I had to obey him, had to live. That he was able to do this while undergoing a like fate to mine is a fair insight into the man my da is. That I lived was something that took me a very long time to forgive him for.

I do not know, nor do I wish to, how long I lived as a werewolf serving my grandmother. It could have been a decade or centuries, though I think it was closer to the latter than the former. It was long enough that I had time to forget my given name. I deliberately left it behind because I was no longer that person, but I had not thought to lose it altogether. My name was not the only memory I lost.

I no longer remembered my first wife’s face or the faces of my children. Though sometimes in dreams, even all these centuries later, I hear the cry of “Taid! Taid!” as a child calls for his father. The voice, I believe, is that of my firstborn son. In the dream, he is lost, and I cannot find him no matter where I look.

My da likes to say that sometimes forgetfulness is a gift. Perhaps had I remembered them clearly, remembered what I’d once had, I would not have survived my time serving the witch. I learned to live in the moment, and the wolf who shared my body and soul made it easy: a beast feels no remorse for the past nor hope for the future.

THREE

Once upon a time, there was a fair maiden of the faerie courts who rode away from a hunting party, chasing something she could glimpse just ahead of her. Eventually she came to a glade where a strange and handsome man awaited her with food and drink. She ate the food and drank his wine and stayed with the lord of the forest even when the rest of her people found her, sending them back to the court without her.

Time passed, and she gave birth to a girl child who grew up as talented as she was wise. In a human tale, this couple would have had a happily-ever-after ending. But the fae are not human, and they live a very, very long time. Happily-ever-after is seldom long enough for them, and that was true for these two lovers. But for a time they were as happy as any.

They called their daughter Ariana, which means silver, as she early on had an affinity for that metal. As she grew up, it became apparent that her power harked back to the height of fae glory. By the time she reached adulthood, her power outshone even the forest lord’s, and he was centuries old and steeped with the magic of the forest.

It is true that the high-court fae were notoriously fickle. It is also true that a forest lord has two aspects: the first is civilized and beautiful as any of the Tuatha Dé Danann, the second is wild as the forest he rules. The sidhe lady eventually grew bored, or perhaps her distaste for her lover’s wilder half became too strong. Whatever the reason, she left her grown daughter and her lover without a farewell or notice, to return to the court.

The forest lord mourned his lover only briefly, for his kind, too, are as light in their affections as they are terrible in their hatreds. For a while after she left, he still loved his daughter and took joy in her. But when her power eclipsed his own, he grew jealous and spiteful. When the other fae took notice of her gifts and came to her with gold and jewels to entice her to share her magic, his jealousy outgrew his love and made it as nothing.

FOUR

The pack customarily bedded down in the woods behind the witch’s cottage. It was mountainous there, but not particularly cold, though winter still held snow and autumn a fine frost. Our coats were thick, and the interior of the cottage was smoky, too warm, and reeked unpleasantly of rotting things both physical and spiritual.

I don’t know about my da or the others, but I was happy to be out of the witch’s way as much as possible. She kept us hidden from those who sought her services, both as unseen protection—because she dealt with powerful and dread beings—and as a precaution because she only mostly controlled us. My da she never let too near her unless she had some of the other, more obedient wolves nearby.

• • •

My father, curled up by himself, raised his head as I came back from hunting. He stood and gave me a look before turning and trotting off into the woods where the leaves were ruddy and gold. I hesitated, but even then, the obedience was a part of our relationship. Instead of settling down to sleep until morning as I had planned, I stretched twice, then ran in his trail until I caught up. Though I didn’t look behind me, I knew that the others followed—as they always did.

At first I thought the other wolves followed us to spy for the witch, but time had proven that wrong. There were six of us werewolves, seven really, though we all knew that Adda was dying—he had trouble stumbling down the trail into the hollow, and I would have to help him up it when we returned.

I had the impression that my father had known some of the wolves from his childhood, but he never confirmed or denied it. He never spoke to them or of them when we were in human form—and they never left their wolf shape.

Da had found a small sheltered hollow in the lee of a downed oak shortly after the witch had brought us here. It served to keep us hidden and offered some protection from the weather for our naked bodies. Even though my human skin didn’t get cold as it had before the wolf entered my soul, skin was not as good as fur. It wasn’t winter yet, but the leaves had begun to change to autumn’s colors, and there was a bite to the air.

Da began his change as soon as we were in the oak’s protection, but instead of following his example as I usually did, I hesitated. Life was easier when I let the wolf rule the man. The wolf killed and killed, and it did not turn his stomach or make him mourn for the creature he used to be.

Da saw that I was hesitating and growled at me—a demand the wolf wouldn’t disobey even if I wanted to.

It hurt. I don’t know how my father even figured out that we could change back to human. I didn’t remember doing it the first time—if I thought about it too long, there were a frightening number of things I couldn’t remember very well. It had taken me a while before I realized that, when my grandmother chose to use my pain to feed her magic, she sometimes stole more than just blood or flesh.

Skin absorbing fur felt like bee stings. The crack of bone was no less painful than a real break. The witch didn’t want her wolves to turn human, but I didn’t understand that then. Didn’t understand how her magic fought the change to human—I just knew that it hurt. She must have known we changed into our human skins. I do not know why she didn’t interrupt. Perhaps she was more afraid of my father than she let on.

“Why are we still doing this?” I asked Da while I was still on hands and knees and sweating from the required effort. “What good does it do except to remind us of what we once were?”

He frowned at me. “I made a promise to your mother, boy. When I told her what my blood was, I promised that I would never allow you to stay in my mother’s hands. If you lose your humanity to the wolf—then my mother has won.”

I stood up, waited until I was steady on my feet, then raised my hands and turned around slowly so he could see all of me, naked and filthy. “There is more to being human than the resemblance I bear to a man, Da. I have left humanity so far behind . . .”

“No,” he growled. He jerked his chin toward the other wolves. “Not like they have. You know right from wrong. Good from evil.”

“It would be easier if I could forget.” I knew what he would say even before he said it; he was not fond of self-pity, my da.

“Easier doesn’t mean better.” He didn’t say anything more. We never talked much at times like these, when he required me to take on human form. What was there to say? Neither of us wanted to talk of people long dead, nor of the day just past, or the one to come.

He believed that his mother would grow complacent and make a mistake. I had believed him long past foolish hope, but years and decades, and then tens of decades had worn my faith away as a river wears away stone. But I loved my da, and I would not hurt him more with my disbelief—let him believe in a better end than I saw. The end would come whatever we believed, and he found comfort in that future he saw for us. I did not tell him that even if we broke free—we would still be the monsters she had made us. My da, he was a smart man, he knew that as well as I did.

The other wolves waited, their eyes trained on my da. But it was the soft whine from Adda that my da acquiesced to. He sat down on the ground, threw back his head, and sang. I settled with my back to the oak and listened.

His voice had lost the old man’s quaver I’d noticed in that last winter we’d spent together as humans, just as both of us had lost the silver hair and the aging skin. Made young again by my grandmother’s magic or the bite of the wolf, I had no reason to ask or care.

My father had no instrument but that with which he was born, but that was fine indeed. When he sang, the others gathered around closely, but he only looked at the dying wolf, who laid his muzzle on my father’s naked thigh and listened as his breath wheezed in and out. The music and the touch of my da’s hand seemed to comfort him.

Witches use the suffering of others for their power, and a werewolf could suffer a great deal before he died. The first sign that Adda was dying was when his ears never grew back quite right. Healthy, we could regrow bits and pieces we lost. Instead of leaving him be, letting him get stronger as she’d done a time or two to others, she’d taken his left front paw when she needed to harvest his pain for her power. We all did what we could for him. When he died, she would spend time with all of us again, until someone started to weaken. Then she would single him out and kill him by inches.

There had been two other wolves who had died that slow death, but my father had not sung to them. Had not sung at all in all the years of our captivity until this wolf had appealed to him without words. I didn’t know why this wolf was different—and I would not ask him.

After a while, I joined in Da’s song. Our voices worked well together, as they always had. Music hurt more than the shift to human had because music recalled better days, days when I had loved and was loved in return, days when the turning of seasons had meaning. But it hurt worse not to sing. Moreover, when it brought my father some bits of joy, even in the darkest day, how could I not sing?

• • •

When change came, it snuck up on me. I did not recognize it for what it was when it began. Autumn ruled, still, but the nights were longer, and I could catch the acrid smell of snow in the air. Not today or the next day, but sometime in the next week there would be a storm.

I was not far from the cottage when I spied one of the fair folk coming to call on the witch. That was unusual because the fair folk, the Tylwyth Teg, had their own powers and usually would have no truck with witchcraft. He was, as they all were, beautiful: tall with eyes as deep blue as the winter sea under dark skies. His skin was silvery with cracks of darkness like the bark of the bedwyn.

Before my grandmother turned me into this beast I had never seen a fae, though I’d heard stories about them. They were still a rare enough sight to attract my interest. After a brief hesitation, I abandoned the rabbit’s trail I’d been following to ghost behind the fae instead.

Tromping through the remains of the autumn leaves in the witch’s woods with no weapon in his hand and looking neither left nor right, this one looked as though he would be easy prey.

I knew better.

The fae were tough, vicious, and deadly—especially the ones that strode through the forest as though they owned it. The lesser fae mostly stayed to the shadows and kept out of the way of things with big, sharp teeth. This one was not one of the Tuatha Dé Danann, the high-court lords, who, above all else, my grandmother feared, so I was under no obligation of her magical chains to report his intrusion. But he was a power; I could feel the forest’s attention upon him.

I moved closer to let my nose get a better read on this one. His track smelled of bitterness and jealousy, small, sniveling emotions, though his body language and the forest alertness spoke of his power. I stayed out of his sight as he walked directly to the clearing where the witch made her home.

He rapped sharply on the door, and my grandmother opened it. She was dressed in a thin shift that left nothing to the imagination, and her thick sandy hair glimmered in the sun like honey pouring over her shoulders and hips. She raised her eyebrows when she got a good look, but she stepped back from the entry and let him in without protest.

Curiosity had me skulking to the side of the building and pressing my ear to the wall. She didn’t know we could hear what went on in the cottage, and we weren’t telling her.

“I am surprised,” my grandmother said coyly, “to see one of your ilk here calling on such as me.”

She was pretty, my grandmother, but not as beautiful as the fair folk; nor was she stupid. If she sounded coy, it was to make the fae believe her less than she was. Powerful things in his world didn’t bow and scrape or creep; they attacked from the front with plenty of warning.

“I am the lord of this forest,” he told her.

She believed the forest was hers; indeed, the locals called it the Witch’s Woods.

“I know, I know,” she said without hesitation, and her disdain was sly and hidden. “The birds whisper it to me, and the wind sings with your power. But two nights ago a pair of faery sight hounds came to me. They wore coats of white and rust, and in that way I knew them for fear hounds, the banehounds of old. So fearsome they were, as to stop the very heart in my chest. They came to my dreams and told me that they were gone away. That you could no more hold them obedient. They broke free of your leash. Such creatures do not make good slaves, so they told me.” Her voice was innocent and light—but I could feel the malice in her intent.

“Take care, witch,” he said.

“They left a promise and a warning for you,” she said, her voice softening. “They said that the power you threw away to pad your vanity will not return to you because the followers of the sacrificed god have reached our shores. Already, Underhill writhes under their cold iron and colder prayers. In a few centuries, they will bind the magic in this land, and all the fae will be powerless before them.”

I heard a noise, the sound of flat hand meeting cheek, and smirked inwardly because I cared not a smidgen for either of them. He had hit her, and he would pay dearly for it.

“You overstep yourself, witch,” he snarled. “You are here on my sufferance, your presence debases my forest with foulness, and you draw the mortals who seek you through my lands.”

There was a little silence.

I wondered if we would feast on a forest lord tonight. I licked my lips. Hunting had been lean within the area around the cottage where we could roam without leave from the witch, and she had not been inclined to allow us to forage farther afield.

“I meant no disrespect, sir,” she said in an obsequious voice that managed to convey fear and respect. Oh, yes, I thought, we would dine on this one. “I only relay information I have been given. I thought you came because you needed something from me. Did you come to drive me away?”

I could hear the rustle of fabric as he paced.

“I need to call my hounds again,” the fae lord said, his voice low and vicious. “I have a task to set them to. You will make it possible, or you will not need to worry about where you might live.”

“Yes, yes, of course. I understand, sir,” her voice was sweet and honey-soft. “Is your need life-and-death? Or simply desire?”

There was a long pause.

“I cannot help if you do not tell me,” she pled. “My magic responds to need. I must know what you want and how much you want it.” I wondered why the fae could not hear the lie as clearly as I could—but he did not know her, and she lied very well. The fae lied not at all, and so were not always good at seeing untruths when they were uttered.

“Yes,” his answer to her was reluctant. “Life-and-death. My word has been given to someone who will destroy me if I cannot keep it.”

“Then I can do something,” said my grandmother briskly, as if a servile tone had never touched her voice. “I can give you power to call hounds. But, as I am sure you know, my power works on sacrifice. For this, the cost will be dear.”

“Not just any hounds,” he said sharply, thinking he saw her trap. The fae didn’t lie, but deception was an art form to them. “The magical beasts.”

I didn’t need to see her smile to feel her satisfaction as he came to her trap without seeing it at all. He was prey, no matter how powerful he was. He was not clever enough to escape her—and she would forgive neither the slap nor the threat.

“Magical beasts in doglike form,” she clarified. He hadn’t listened to her. She’d told him that he wouldn’t be able to call the fae dogs again. But she was not fae. She could lie all the time—and she did so when it suited her. But I could tell that she had not lied about that. Magical beasts in doglike form—that would be us.

She meant to let him call wolves when he expected his own hounds. Maybe, maybe if he had controlled the fae banehounds, who were fearsome beasts, he could control us. For a while.

“Yes,” the forest lord said, not questioning her phrasing. After all, she was only responding to his request to clarify. He never thought to ask her what other magical doglike beasts there were nearby.

I didn’t know if he was truly stupid, or if he did not recognize the threat she represented. The fae were proud, worse back in those days, when they ruled, and the humans feared. They did not easily take notice of threats that were not fae in origin.

“I can do that,” she said slowly, as if after careful consideration. “You will pay me a pound of silver.”

“Fine,” he said easily, though it was more than she’d normally have seen in ten years of work.

“That is the cost you owe me,” she told him. “But the magic will cost your hand&#

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...