- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

“A firework of a fantasy novel: vibrant, explosive, deliciously dangerous, and impossibly fun.” ―Tasha Suri

Strap in for a thrilling adventure in the sequel to Davinia Evans's wickedly entertaining debut fantasy that follows our favorite irreverent alchemists, high society ladies, and swashbuckling street gangs as they wrestle with the nature of reality itself.

Siyon Velo might be acknowledged as the Alchemist. He may even have stabilized the planes and stopped Bezim from ever shaking into the sea again. But that doesn’t mean he has any idea what he’s doing—and it won’t be long before everyone knows it.

To make things worse, mythical creatures once confined to operas and myths are spotted around Bezim. A djinn invades Zagiri’s garden party, and whispers of a naga slither across Anahid’s Flower district card tables. Magic is waking up in the Mundane. It’s up to Siyon to figure out a way to stop it, or everything he’s worked so hard to save will come crashing down.

Praise for The Burnished City:

"I loved getting lost in this dazzling debut." ―Shannon Chakraborty, author of The City of Brass

"Sheer, glorious fun!" ―Freya Marske, author of A Marvellous Light

The Burnished City

Notorious Sorcerer

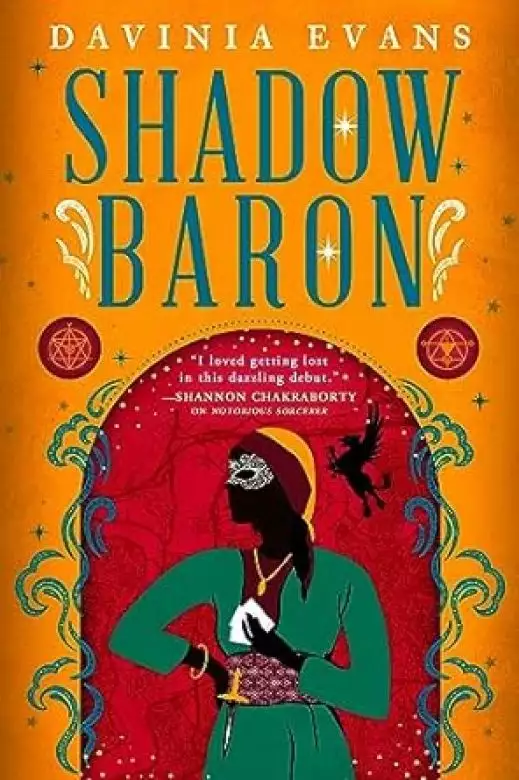

Shadow Baron

Shadow Baron

Release date: November 14, 2023

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Shadow Baron

Davinia Evans

“We’re not holding anyone on sorcery charges.”

She was so sulky that Siyon couldn’t resist propping an elbow on the counter and giving her a grin. “Yeah, but you’d say that even if you were.” Her eyes widened in glorious outrage, but he was actually here for a reason, so Siyon snipped the line on her ire before she could reel it all the way in. “I’m here to see Olenka; is she about?”

The clerk sniffed. “Wait here, and I’ll see if Sergeant White is available to speak with you.”

The benches that lined the waiting area were still masterworks of discomfort, but at least no one else seemed to recognise him. Probably weren’t expecting the Sorcerer Velo to have the freckles and reddish hair of a Dockside mongrel; everyone knew he was noble and grand and flamboyantly dressed.

Siyon had slung that old purple coat of Nihath’s into a cupboard and happily forgotten which one.

Nearly two months had passed since the exciting events of the summer—when Enkin Danelani, son of the prefect, was saved from the ravages of a harpy (or so the story went) and Siyon Velo had…

Well, the stories never agreed on quite what Siyon Velo had done, but clearly it had been thrilling, and dashing, and entirely aboveboard because the Council now recognised him as the Sorcerer. Even if he’d apparently brought a demon into the Mundane, it was fine, because he had her bound to his every whim.

The first time Laxmi had heard that, she’d laughed so hard she melted into oily shadow.

Very little of the breathless gossip bore much of a resemblance to what Siyon remembered happening. He wished he’d merely snapped his fingers to summon the other Powers to parlay, instead of cutting a gate to the void between planes with a kitchen knife and his own desperation.

He wished he hadn’t fallen through that gate holding Izmirlian Hisarani, his fatally wounded love, in his arms.

He wished…

It hardly mattered, did it? Wishes weren’t worth much.

No one here looked twice at him, just an unshaven lout who slumped in a corner and stretched out his long legs, crossing scuffed boots at the ankle. Siyon rubbed at the headache that loitered behind his left eye like an alley cat waiting to pounce. Part lack of sleep, with his dreams dark and strange these days. Part too much reading, but he still had so much knowledge to catch up on, and no idea where the real answers might be when the wisdom of the vaunted Kolah Negedi had been proven… incomplete.

Mostly, though, the headache was the fault of the planar emanations.

They’d started the moment Siyon had stepped back out of the void—or rather, been hauled out by Zagiri. Energy skittering and skewing all around him, in bright swirls of Aethyreal mist, sharp and shooting Empyreal sparks, sinuous eddies and coiling smears of the Abyss. Every bloody movement echoed queasily in Siyon’s vision.

At the time, he’d thought it the aftereffects of what had happened. Of what he’d done. Of becoming the Power of the Mundane.

But it hadn’t gone away. Even here in the inquisitors’ waiting room, Empyreal gold frosted the wall with stiff righteousness, and knots of Abyss and Aethyr tangled in the white-knuckled fingers of those waiting on news of their loved ones… or perhaps their partners in crime. Was that twist of purple and green worry, or guilt?

If Siyon knew that—if he knew even a little more about what he was seeing, or why—he’d feel a lot better about a great many things. What all this meant. What it was for. What he was supposed to be doing.

He was the Power of the Mundane… and he still didn’t have a clue.

Someone kicked his ankle, and Siyon jerked upright. Had he nearly fallen asleep? When had his eyes closed?

He blinked up into a hawk-sharp face, haloed by a frizz of dirty blonde curls limned by lantern light. “I should let the desk clerk arrest you for slandering the inquisitors,” Olenka said, looking down on him like an angel from on high. Apt, since she’d once been one, before she fell into the Mundane. “The harpy’s a bad influence on you.”

“I’m offended you think I need help,” Siyon retorted. As he levered creakily up to his feet, he added, “Sergeant White?”

She snorted. “They wanted another name on the paperwork. I didn’t think any of my others would really be suitable.” Now Siyon was extremely curious about Empyreal naming conventions, but she just said “Come on” and strode away.

He needed her help, so he scurried along after her, which he regretted when she ushered him brusquely into an empty interview room. The furniture was stark and clean and tidy, but there were all sorts of unpleasant memories skittering around the bare, unsympathetic corners.

“I’d rather not—” Siyon tried to slide right back out again, but Olenka shut the door and stood against it with her arms crossed like she was barring the way to something she disapproved of. “Don’t want your friends to see you with me?” Siyon quipped, perching on the corner of the interrogation table. He wasn’t taking the victim’s chair, no thanks. But then he realised—the name, this secrecy… “None of them know what you are, do they?”

Siyon supposed he couldn’t blame her. Given that her colleagues worked in the branch of the inquisitors that policed the practice of alchemy, they might have thorny opinions about sharing a desk with a fallen denizen of another plane. And that whole branch had enough problems, with one of their star captains—and Olenka’s former boss—now banished from their ranks in disgrace.

Sometimes Siyon wondered what had become of Vartan Xhanari… but he didn’t wonder too hard. Especially not when he was sitting in a room much like the one where Xhanari had threatened him with the executioner’s poison. Not when he still heard in his nightmares the rattle of Izmirlian’s breath around the crossbow bolt Xhanari had put in his throat.

Xhanari had sent him a letter, soon after everything had happened. It might have contained an apology. Siyon hadn’t read it. He’d set fire to it and let Laxmi make tea from the ashes.

Here and now, Olenka—now a sergeant in her own right—entirely ignored his questions. “Don’t you have work you should be doing?”

Once upon a time, work for Siyon had meant carving a gate and throwing himself into another plane in search of the sort of bits and pieces an alchemist might pay him for, while dodging the attentions of the native monsters and beings… like Olenka. She’d once tried to sever the tether holding him to the Mundane with her broadsword.

Strange that he sort of missed it. At least his problems had been simple ones. Occasionally six feet long and on fire, but simple.

“That’s actually why I’m here,” he said. “You mentioned that the inqs might be less nervous—and less confrontational—if they weren’t worried that I might turn them into frogs.”

“Frogs did not come into it,” Olenka corrected stonily.

Siyon ignored her; that hardly seemed an important detail. “So I’ve been trying to imbue a nullification into the silver of your badges—”

Her snort interrupted him. “How’s that working out for you?”

Siyon was starting to think it might be impossible, actually. He’d even discussed it with Nihath Joddani, who had been known to trade Siyon imbued gemstones, and who would at least talk to Siyon instead of trying to harangue him about how Negedi could be interpreted to suit current events if you turned it upside down and squinted. (Ink and ashes, but Siyon missed Auntie Geryss fiercely some days.)

But none of that was the point right now. “But then I thought, your dowsing rods have a certain nullifying effect, right? That’s what they’re for. So could I take a quick squiz at one?”

Olenka sighed and rubbed at her face, like she had the twin sibling of Siyon’s headache (which was still there, prowling around looking for an excuse to sink its claws in). The gust of her exhaled breath billowed a faint shimmer of Empyreal white. “If you’re doing this to get the attention of the Working Group on Oblique Methods—”

“No,” Siyon objected. But his voice sounded sulky and defensive even to his own ears. The Working Group on Oblique Methods was the typically circuitous name of the Council subcommittee responsible for overseeing the practice of alchemy in Bezim.

They’d sent Siyon a letter as well. It had been florid and beautifully ornamented and had thanked him for his service and assured him that they respected his very valuable time too much to ask him to do anything and would, in effect, be having nothing to do with him.

It was the politest and fanciest way Siyon had ever been banned from an establishment. Not that he wanted to spend his time sitting in a meeting of the sorts of azatani who thought squeaking their way through the labyrinthine processes of the Council of Bezim was a riotous good time.

But the governance of Bezim worked through those processes, and those committees. If anything was ever going to change about the parts of alchemy that were still illegal, it would have to start in the Working Group.

So yes, Siyon had sort of hoped that if he could present the inquisitors with an immunity against any untoward effects of stray alchemy, that might suggest that he should be more directly involved in things.

From the flat look Olenka was giving him, that little hope was both transparent and naive. But all she said was: “The dowsing rods are cold-forged star-iron. They’re Mundane—entirely Mundane—which is part of why they react to material of other planes.”

No, dammit, Siyon had been sure he was onto something here. “But couldn’t I just—”

“I assumed,” Olenka said over him, “that you were here for something actually useful, like offering some help with the recent disturbances down in Dockside—”

Siyon’s turn to interrupt right back. “Fuck that,” he said, “you and Dockside are welcome to each other.”

She rolled on without blinking. “—or bringing some insight about our spate of curse reports, or even trying to get involved with the trial of that poor bastard up in courtroom three, but instead—”

Siyon stood up from the edge of the table, a chill down his back like someone had frisked him with a dowsing rod. “What poor bastard? The clerk said you didn’t have anyone on sorcery charges.”

Olenka considered him with her flat grey eyes. “They’re not straight sorcery charges.”

Probably because every time the inqs had brought that charge in the last two months, Siyon had shown up in the courtroom—whether as a called witness or merely an unscheduled ruckus.

Three alchemists had been executed for sorcery during the chaos over the summer—chaos that Siyon had been instrumental in creating. The Margravine Othissa, Talyar the weaver, and a third whose name Siyon had never learned because his family had requested the records be sealed.

No one else was getting executed if he could help it. And he could. The definition of sorcery in the laws of Bezim stated that it was endangering the city through the practice of alchemy.

There was no danger to the city from alchemy, not anymore. Not since Siyon had become the Alchemist, filling a long-vacant gap in the planes and bringing the Mundane back into balance. There couldn’t be another Sundering now. All the alchemists of the Summer Club—all the trusted and educated and legal alchemists—agreed.

The first time a judge had accepted that reasoning and thrown out the case, Siyon had smugly suggested that the law should be changed. Two months now, and it still hadn’t happened. These things, he’d been told, took time. It was (you guessed it) the purview of the Working Group on Oblique Methods.

Meanwhile, the cog-toothed wheels of justice kept turning as they were.

Unless he stuck a wedge in them.

“Velo!” Olenka shouted after him, but Siyon wasn’t waiting. Not when another life might hang in the balance.

Unlike the dutiful severity of the inquisitors’ annex, the corridors of the Palace of Justice proper were elegantly adorned with gilt-framed paintings and niche-ensconced vases. Even the floor tiling was ornate, to reflect the stately dignity of the azatani government.

Siyon had no dignity. He sprinted down the halls, dodging around startled clerks, leaving objections and ruffled papers in his wake. He turned whichever way looked fancier, until he saw the gold-railed mezzanine overlooking the grand entrance hall.

The magnificently sweeping staircase, curving around the wall beneath the glorious copper dome, was crowded with gossiping groups. Siyon hoisted himself up on the banister and slid down with a merry shout of “Coming through!”

He stumbled upon landing, his breath coming short. A couple of months off running the tiles, and he was already an embarrassment to any bravi tribe. But Siyon pushed on, across the grand mosaic of the entrance hall and down the corridor to the courtrooms. The third set of doors was shut, guarded by a frowning white-sashed steward and a bronze sign reading COURT IN SESSION that sizzled with Empyreal energy.

“I need to get in,” Siyon gasped. “I’m Siyon Velo.”

The steward frowned more deeply. Now Siyon wished he’d brought the purple coat. Hard to summon up the majesty of the Sorcerer Velo when he was heaving for breath.

And then the steward’s face hurriedly cleared, as he lurched into the stiffest pose of being at attention Siyon had ever seen.

A sharp voice behind him said, “What are you doing here? I sent a runner to tell you to stay out of this.”

Siyon winced and turned to face Syrah Danelani, prefect of Bezim. Centre of an officious knot of clerks and helpers, she was a column of gleaming formal white, right down to the pearls braided into the crown of her ink-dark hair—the blindingly pure authority that the azatani of Bezim had grabbed for themselves and run with.

Resisting the urge to rub at his unshaven chin or further ruffle up his hair, Siyon said, “Ah. Must have missed me.”

One of her eyebrows lifted slightly, as if she doubted his answer but wasn’t surprised by the situation. She probably wasn’t; likely they both knew that Siyon would have come running the moment he’d received the message anyway. “You can’t keep doing this,” she said. “There are processes. That’s how stable government works.” But she gestured sharply at the steward. “Well? Open the door.”

The steward leapt to obey. Syrah gestured for Siyon to precede her.

The courtroom was brightly lit with lanterns and even more brightly lit—to Siyon’s sight—with Empyreal zeal. Behind the bench, the magistrate’s white sash gleamed, and there was a nimbus of energy around the grey-uniformed inquisitorial prosecutor, though he developed dark streaks of Abyssal red and green as he caught sight of Siyon and started protesting to the magistrate.

Easier to look at the accused, standing in a white-painted circle. Young, and from the tawny skin tone and high cheekbones probably from somewhere in the Khanate, though more than that was hard to pin down. Possibly this was a belligerent girl, dressed in a tight vest and hardy trousers, or maybe a pretty lad, with hair shaved down to the barest dark fuzz.

The magistrate hammered silence back into the courtroom, enough for Siyon to hear her sigh. “Welcome, Madame Prefect. And Master Velo. Again.”

From behind Siyon, Syrah Danelani said, “Please carry on. I am merely here to observe.”

Siyon wasn’t. He blinked at the magistrate, and maybe he did recognise her through the lingering Empyreal haze. He tried a grin. “Your honour, you know what I’m going to say.”

That there was no charge of sorcery to be answered. That there could be no charge of sorcery—which required not just unlicensed alchemical practice, but risk to the city—when Siyon had rebalanced the planes.

Allegedly. Especially when the world was a roiling soup of coiling planar energy like this, Siyon had his doubts, but it didn’t seem to bother anyone else. As far as the other alchemists were concerned, everything was fine.

The prosecutor shot Siyon an unpleasant little smirk, tugging his grey tunic straight. “Your honour,” he echoed, “as I was saying before this interruption, the accused stands charged with the sorcerous use of foreign magic.”

The what? “That’s impossible.”

The magistrate glanced nervously over Siyon’s shoulder, presumably at the prefect. Merely observing. “Do you know Mayar el-Kartou?”

“Just Mayar,” the accused interjected. They were standing with arms tight-crossed over their leather vest—actually, was that a bravi vest? Siyon’s gaze darted down—no sabre or belt, certainly no badge, but he wouldn’t have wanted to drag his tribe into a courtroom either.

“Never seen ’em before in my life,” Siyon declared, turning back to the magistrate. “But there is no magic; there is only alchemy. And alchemy only works here. So foreign magic isn’t possible.”

“Your honour,” the prosecutor slid in silkily. “Given the tremendous upheavals this man has caused, who is to say any longer what is possible or not?”

Siyon hesitated, caught. He had done the impossible—or what had been considered impossible—more than once in the summer. He’d caught Zagiri, falling from the clock tower. He’d become the Power. And he’d sent Izmirlian Hisarani somewhere else entirely. Though only a handful of people knew about that, and just thinking of it caught the breath in Siyon’s throat.

The magistrate narrowed her eyes. “It hardly matters what is possible outside Bezim when our laws and your remit”—she pointed her mallet at the inquisitor prosecutor—“apply only within the bounds of the city.”

“And the offense occurred within the city,” the prosecutor hurried to say, and flourished a fistful of documents. “I have sworn testimony from a number of accredited practitioners that the effects Mayar el-Kartou was witnessed producing are not alchemically possible without equipment that was nowhere in evidence. Therefore something untoward is afoot.”

Siyon glanced sidelong at the accused again. What had Mayar el-Kartou—just Mayar—been up to?

“Something?” the magistrate repeated, with a little lip purse that might have been distaste. “Superstitions might be running rampant in the city’s alleyways, but if you bring them into my courtroom—”

“Something verified!” The prosecutor brandished the testimony again.

“Something that isn’t alchemy,” Siyon chipped in. After intervening in this many court cases, after doing his reading, after having so many arguments, Siyon knew this particular part of the law as well as the magistrate did. “Not alchemically possible, he said so. Therefore not sorcery.”

The prosecutor scowled like someone had taken away his favourite toy. “The intention of the statute is clearly to—”

“Doesn’t matter,” Siyon interrupted. If he’d learned anything from the past two months of wrangling with this, it was that intention didn’t bail any water. The precise wording—the infinitely argued-over wording—did. “You want to start calling other things sorcery, you’re going to have to change the laws.”

He did grin then, wide and feral. Please, bring the laws up for discussion. Wherever they did it—the Working Group on Oblique Methods, or any other of the infinite labyrinthine committees that made up the working of the government like a school of myriad fish—Siyon would find a way to get at it. He’d find a way, and he’d worry the thing to shreds like a shark with a grudge.

“In the meantime,” the magistrate declared, cheerful as a woman whose morning schedule had magically cleared itself, “I conclude there is no charge of sorcery to be answered by Mayar el-Kartou.”

The courtroom erupted. Siyon hadn’t realised the viewing gallery above—usually sparsely populated—was crowded today. There were a dozen black-clad bravi up there—so just-Mayar was a bravi—and a handful of shabbily dressed folk that he thought might be hedgewizards and other unlicensed alchemists, and there was even a knot of Khanate caravanners, in their vests and trousers and beaded braids.

All of them seemed pretty jubilant about the result.

Over the noise, the prosecutor was shouting, “—other charges can be brought!” And the magistrate was not quite shouting back about reliance on due process and the importance of thorough procedure.

When Siyon glanced back at the accused circle—brimful as a festival cup with questions for Mayar el-Kartou—it was already empty, a flash of black leathers disappearing toward the door.

And Syrah Danelani was in the way of Siyon’s pursuit, with her attendant clerks fanned out behind her. She didn’t precisely look unhappy with how things had turned out, but she also didn’t look all that pleased with Siyon. “This isn’t the best way to go about change,” she told him, quiet beneath the noise of the crowd. “You’re the Power of the Mundane, Velo. You have better things to do with your time.”

“Like what?” Siyon demanded, hoping it sounded more like a challenge than it felt.

He was the Power of the Mundane, and he didn’t know what that meant. He didn’t know what he was for. He didn’t know what he should be doing.

But he could do this. So he would. He’d hammer at the gates until they let him in, if he had to.

The prefect of the city sighed and turned to leave, tossing over her shoulder in parting: “At least get some sleep. You look like shit.”

Zagiri Savani had been at the hippodrome all afternoon, and she’d yet to see a horse, though apparently the Basilisk team had brought in a new driver from Lyraea, and despite some controversy with his paperwork, he’d been performing magnificently. Just magnificently.

She eased out of yet another conversation—the way Anahid had taught her, with a pleasant smile and a vague do excuse me—and slipped away, eyes scanning the room. It was long, and crowded, and swathed in sparkling little alchemical lanterns and even more sparkling society. Everyone who mattered—the highest tiers of the azatani and those lower with aspirations to rise—was here at the final formal social event of the year.

The hippodrome crowds were a faint and distant roar, and the racing itself unimportant beside the fiercer competitions underway here in the gallery. Refreshment tables ran the entire length of the inner wall, with the platters of delicate little nibbles and bottles of sparkling djinn-wine continually refreshed by the stewards. Along the outer wall, pairs of open doors framed with gauzy curtains let out onto a long balcony. The view was magnificent out there—not so much the nearby markets and bordellos and the Khanate caravanserai as the sight of the city wall rising over the rocky hills, with the domes and towers of Bezim glowing in the afternoon sun.

That autumn sun was still gloriously warm, but very few people were out on the balcony. All the opportunities were in here, and Zagiri was not the only person prowling in pursuit of them.

She slipped between all manner of conversations, keeping a careful ear out, the way Anahid had told her again and again she should. Most of the chatter had to do, one way or another, with the trade and discovery voyages that would soon be setting forth from the harbour, now that the storms of summer were abating. There were complaints about the usual delays and ructions in Dockside, from the workers outfitting the vessels. (Zagiri gathered it was the Laders’ Guild this year that was getting particularly difficult.) More than a few guests were actually buying and selling last-minute shares in various ventures. Even the apparently idle gossip and discussions of Salt Festival plans weren’t really all that frivolous, as families pried at one another’s affairs, seeking any angle that might help them turn a greater profit in the year to come. There was even a knot of hushed debate about the ongoing turmoil in the Northern territories, and whether it might be dying down to the point that trade could be resumed.

Amid all this, there was also the ostensible reason for today’s event. Up and down the gallery, the young azatani women who’d signed up to be sponsors at next year’s Harbour Master’s Ball were adorned by a pale yellow sash.

Zagiri was among them, her sash pinned so ruthlessly straight across her dress that she ran the risk of being stabbed if she turned around too fast. But while the other young ladies were considering the most useful debutantes to sponsor—and possibly even starting to flirt with the marriage offers they could consider after the Ball—Zagiri was stalking a very different prey.

She wanted a clerkship. She wanted a foothold in the Council, just a place to start. A chance to eventually become one of the people who could make—or change—the laws of the city.

A laughably modest ambition, almost flimsy in how small it was. What Zagiri wanted was to never again see the things she had over the summer, when alchemists and provisioners had cowered in the crypt of the Little Bracken safe house, fleeing a sudden crackdown on their illegal but previously tolerated occupations. She wanted the laws changed, the systems changed, the unfairness eradicated…

And she could do it. She was azatani after all. She was allowed in those halls and those decisions.

She’d left it far too late, of course. All of the entry positions for this winter had been assigned last autumn, in a rigorous and very competitive process.

All of the entry positions but one.

Or rather, it had been assigned, and it had been taken up a little early, but—or so Zagiri had heard—the young azatan had just been fired in disgrace.

There was a gap. If she was quick and keen, Zagiri could slide right into it. Otherwise, she’d have to wait another year to even get started.

This was far too important to leave anything to chance. So Zagiri had traded bravi favours to learn that the councillor now in need of a clerk was Azatan Palokani; she’d had to throw a duel to one of the Bleeding Dawn, losing flashily and making him look good, and she considered it worth the price. She’d asked her father and cousin for all the details on Palokani’s history, interests, trading concerns. She’d spent days reading up on the jurisdiction of the Domestic Handling Committee, which Palokani was the undersecretary of. (Frankly it sounded unbelievably tedious, all paving and public works and festival planning, but Zagiri wasn’t going to be picky right now.) And Anahid had nudged all her own contacts until she’d managed an introduction to Palokani’s wife, which meant today Zagiri should be able to…

Ah, there she was. Anahid was standing in conversation with the Palokanis—the azata in a red headscarf as was her habit. Zagiri’s sister was dressed far less flamboyantly, in a darker shade of the same blue Zagiri was wearing, but Anahid’s ears glittered with elegantly set Northern turquoise baubles that Zagiri knew she’d won at a game of carrick in the Flower district.

She wasn’t sure what she was most proud of Anahid for: playing so well or brazenly wearing her winnings among people who would be scandalised if they knew how she came by them.

Despite that little piece of outrage, Anahid looked utterly immaculate, her face serene and her grooming perfect. But as Zagiri caught her eye, her sister lifted a net-gloved hand to touch at one of her earrings.

That was the signal.

Zagiri moved quickly, grabbing a plate from the refreshments table and loading it briskly. She spotted a couple of young azatans in the crowd, heads close together as they watched the Palokanis closely, but Anahid had them so engaged in animated conversation—bless her—that it would be impolite to interrupt.

Unless you had a way in.

Zagiri detoured around a pair of startlingly blonde women in strange attire—from the North, she realised, and drawing their share of attention for it—and leapt into the fray before she could outthink herself. “Ana, look what—oh, I do beg your pardon.”

She gave a very deferential nod, halfway to a bow, to Azatan Palokani, and one only slightly shallower to his wife (who wasn’t a councillor, but was the family trader, and wealthy enough that her husband had taken her name upon marriage).

As she did, Anahid was saying, “Oh, do you know my sister, Zagiri? She’ll be sponsoring next year, we’re so very proud.”

Which was Zagiri’s cue to protest that she felt like she was lagging behind, having waited until nineteen to sponsor. Almost true—Zagiri certainly was one of the older sponsors in the room—but they’d decided to make a point of it because Azata Palokani had waited as well, and now she smiled genially and made all the right assurances. Everything was going according to Anahid’s plan, and Zagiri gave thanks for such a surprisingly cunning sister.

“I’m so sorry to have interrupted,” she continued, lifting her plate. “But look, Ana, they have Storm Coast pepper prawns.”

Azatan Palokani’s eyes lit up, just as they’d anticipated. Zagiri offered the plate around, and they fell into discussing the various trading routes of pepper—a dominant good in the Palokani portfolio. Anahid asked the azata a question about outfitting trade vessels for easterly voyaging (which Zagiri knew Anahid found largely boring, but no one el

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...