- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

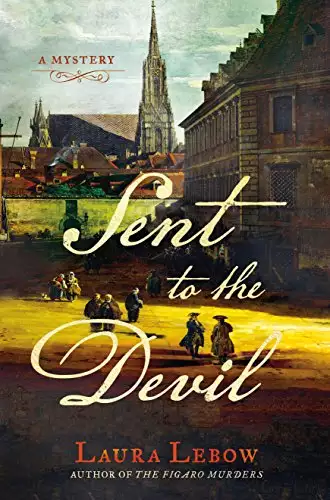

Synopsis

In 1788 Vienna, Court Poet Lorenzo Da Ponte is putting some finishing touches on the libretto for the premiere of his new opera with Mozart, Don Giovanni. A huge success when it debuted in Prague, the Emperor has decreed that it shall be performed in Vienna. But Joseph II is off prosecuting a less-than-popular war against the Turks, and the city itself is in a bit of turmoil. There are voices protesting the war, others who see Turks around every corner.

Da Ponte, however, just wants to do his work and enjoy life. Alas, these simple desires aren't to be easily fulfilled. First, he's been getting a series of mysterious coded notes from unknown hands, notes that make no sense to him. Then his old friend Alois, a retired priest and academic, is viciously murdered and strange symbols carved into his forehead. Summoned to the police bureau, Da Ponte learns that Alois's murder was not the first. Determined to help find his friend's killer, Da Ponte agrees to help with the secret investigation.

Caught in a crossfire of intrigue both in the world of opera and politics, Da Ponte must find the answer to a riddle and expose a killer before he becomes the next victim.

Release date: April 5, 2016

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Sent to the Devil

Laura Lebow

Monday, April 14, 1788

The second message was waiting on my desk when I arrived at my office.

The cheap paper had been hastily folded, sealed with a messy blob of wax, and its front scrawled with the words “Lorenzo Da Ponte, Court Theater.” I turned it over in my hands. There were no marks on the outside to show that the letter had traveled through the postal system, and no insignia pressed into the wax to identify the sender. I went to my cupboard, placed the note on a high shelf, returned to my desk, and pulled out the aria I had been writing. I had no time this morning for the game my mysterious correspondent insisted on playing.

I’d been working night and day for the last nine months. I am the poet of the Court Theater in Vienna, where I am responsible for editing all of the librettos—the texts—and coordinating the productions of operas performed there. I augment my salary by taking on commissions to write librettos myself, and last fall I had written three at the same time, one for each of the city’s top composers. The opera I had written for my friend Wolfgang Mozart, Don Giovanni, had debuted in Prague six months ago, and had been a big hit there. There was no rest for us after our triumph, however, because soon after, Emperor Joseph II had ordered a performance of the opera here in Vienna. Mozart and I were busy adapting our work to the more sophisticated tastes of the imperial capital. And once Don Giovanni premiered in May, I had commissions for several more librettos. I was tired. Sometimes I wished that I’d been born a Viennese nobleman, instead of a leatherworker’s son from the Veneto who had to work for a living.

But although I was overworked, I had to admit that I was happy with my life in Vienna. I loved my job, and had achieved professional recognition for my talents. I treasured my relationship with the emperor, who had supported me from the very first day he had appointed me to my post. I had a small circle of friends with whom I could discuss literature, art, and music. And lately, I had even returned to writing my own poetry, which was my first love.

When I had edited the aria to my satisfaction, I put it into my satchel. My stomach grumbled as I pulled my watch from my waistcoat pocket. Half past one already! I had an appointment for dinner at two. I closed my satchel and went to the cupboard, where I pulled on my cloak. My eyes went to the high shelf. I sighed, grabbed the message and shoved it into my cloak pocket.

* * *

Outside in the Michaelerplatz—the gateway to the Hofburg, the large complex of buildings that housed the imperial government and the emperor’s personal apartments—small groups of newly inducted soldiers in crisp, shiny uniforms stood under the leaden sky laughing and teasing one another, their smooth faces flushed with excitement. In the Kohlmarkt, I stopped and peeled off my cloak. The spring weather had been unseasonably balmy for a week now.

At the end of the Kohlmarkt, a small crowd had gathered to watch two laborers bang a large board over the entrance of one of the city’s most popular print shops. A large painted sign indicated that it had been closed by the Ministry of Police. The once-free presses of Vienna must now be cautious about what they printed, or suffer the fate of this one. I hurried by. I had had my own encounter with the Ministry of Police two years before, and now tried to avoid trouble whenever possible.

I turned into the Graben. As late as last autumn, the large plaza had been the place to see and be seen for Viennese society, but as the snows of winter melted and the emperor and his troops marched off to war, the large expanse had lost its frivolous air. Instead of promenading down the plaza and stopping to chat with friends, people now hurried to their destinations, greeting one another with nothing but a quick nod.

“We are the aggressors in this war, not the Turks!” Ahead of me, a young man stood on an upended crate at the base of the elaborate plague column that dominated the middle of the Graben. A few shoppers and workmen were gathered around one side of the monument’s enormous plinth, which was decorated with sculptures symbolizing the triumph of faith over disease. I stopped at the back of the group, nodding at a square-jawed man in his early thirties who leaned on an ornate stick next to me.

“Our ally Russia is to blame!” the young man shouted. His features were handsome, but his long hair was tangled and his beard unkempt. He wore a threadbare coat over breeches that were torn at both knees.

“That’s nonsense!”

I started as the man next to me called to the protester.

“Read the papers. The Turks have been stocking arms since the Crimean crisis. They are stirring up the peoples in the Caucasus against Russia.”

“The Turks are just trying to defend themselves, sir,” the orator replied. “Russia provoked them. The emperor was a fool to sign a treaty with—”

My neighbor snorted. “The Turks declared war first!” he shouted. “You are the fool! How can you believe they are an innocent party?”

A group of market women had stopped to watch the argument.

“They had to declare war. They had to defend themselves before Russia’s army grouped along their borders—”

“If the Turks are just defending themselves, as you say, why did they refuse offers by France and Britain to mediate their dispute with Russia?” my neighbor asked.

The war protester turned to the newcomers in the crowd. “Friends, you look like solid citizens of the empire. Do you want your fathers, your sons, your brothers to give their lives for Catherine of Russia’s expansionist policies?”

“No!” a middle-aged woman holding the hand of a young child shouted.

The man left my side and, using his stick for aid, pushed his way to the front of the crowd. His twisted right leg dragged behind him. “Russia is not our enemy,” he shouted at the orator. “You are young and naïve. We need Catherine’s help in keeping the Prussians away from our own borders!”

Two constables approached the assembly. “Everyone move along,” one shouted. The market women turned away.

“We should also have France as an ally against Prussia.” The orator looked down at the crippled man. “The French carry on a large trade with the Turks. By declaring war against the Ottoman Empire, Joseph has alienated the French.”

As the constables continued to press, the group broke up. I lingered as the angry man moved close to the orator’s box. The protester shouted to the backs of the dispersing crowd. “Think of the lives lost already! Our men sitting in that swamp in Semlin waiting for the Russians to distract the Turks in Galicia before we can invade their garrison in Belgrade. How many of our boys will die of disease as the weather gets hotter?”

“That’s Turkish propaganda!” The crippled man shook his fist. “Joseph will be taking Belgrade any day now! The Turks will surrender. Everyone knows how bad morale is in their army. Our boys will be home before the end of summer.”

“How many will never come home?” The young protester looked the man up and down, taking in his dress suit and elegant stick. “It is easy for you to speak in favor of sending them to their deaths, while you sit at home, comfortable in your palace.”

“You insolent swine! How dare you speak to me like that!”

I watched, astonished, as the man raised his stick and swung it at the orator. The young man ducked and fell off the crate. He sprawled on the ground against the low balustrade that surrounded the monument.

“Hey now, stop that, sir.” One of the constables grabbed the assailant’s arm.

“Let go of me!” the man said, his face red with anger. “I am Baron Walther Hennen. I’ll report you to your superior officer.”

The constable withdrew his hand.

Hennen glared at the orator. “As for you—you are one to speak about avoiding service in the war. I know who you are. You had better be careful, or you’ll end up in Semlin before you know it.” He turned and limped angrily in the direction of St. Peter’s Church.

I continued on toward the Stephansplatz. I wasn’t sure what to think about this war. I was not a native Austrian, so I had no emotional connection to the hostilities. But I worried that a prolonged war could affect my life here in Vienna, especially my position at the theater. When the emperor had left a few weeks ago to join the troops at Semlin, he had ordered the city theaters to remain open. If the war dragged on, though, that situation could change, and I might be out of a job. But I knew the emperor well, and I respected his wisdom and trusted his judgment. If he felt it was necessary to support the empress of Russia in her war against the Turks, who was I to question him? I just hoped the Turks could be defeated quickly.

In the Stephansplatz, the buildings were draped in black bunting, as were the main doors of the great cathedral. A funeral mass had been held yesterday for General Peter Albrechts, a hero in the late empress’s war thirty years ago. I had not attended, but I had heard that the crowd of mourners had spilled out of the cathedral.

I walked by the west portal of the cathedral and crossed the small side plaza to a nondescript office building. I climbed four flights of stairs, made my way down a small corridor to the office at its end, and poked my head in the open door.

“Alois?”

“Lorenzo!” Alois Bayer rose from his desk. “I was beginning to worry that I had my dates confused.”

“I’m sorry. I was held up by a disturbance in the Graben,” I explained as I gently returned his embrace. My elderly friend was growing more fragile every time I saw him. “That young man who is always protesting against the war—he and a bystander almost came to blows.”

“Was anyone hurt?”

“No, some constables broke up the fight before any violence occurred,” I said. I settled into the chair next to Alois’s desk and looked around the familiar space. Books were piled on every free surface. I took a deep breath and inhaled one of my favorite smells—the scent of old books punctuated by a slight trace of the peppermint drops Alois ate constantly. A thin straw-filled pallet lay on the floor behind the desk. I frowned. “What is that? Are you sleeping here now? What happened to your room over in the Wollzeile?”

Alois shrugged. “The cathedral needed it for one of the new priests. I don’t mind it here. It gives me more time to study.”

I opened my mouth to object, but closed it as the red tinge of embarrassment spread over his papery cheeks. “Are you ready for dinner?” I asked. “I’d like to try that new catering shop over by the Greek church.”

He hesitated. “I’m not that hungry, Lorenzo. The older I get, the less appetite I have. I have a nice bottle of Tokay. Why don’t we stay here and drink it instead of going out for dinner? We haven’t had a good talk in a long time.”

I shook my head. I knew why he was protesting. Since he had retired from the active priesthood, he lived on a small stipend from the cathedral, and he spent most of his money on books. I worried that he seldom ate a hearty meal, which is why I had made a point of inviting him out today.

“Nonsense,” I said. “We can discuss whatever you want at the catering shop.” I put my hand up as he shook his head. “I invited you out to dinner, and out to dinner you will come.”

“No, no, Lorenzo,” Alois protested. “You have better things to do with your money.”

“Better things to do than spend an afternoon with a good friend, enjoying a delicious meal?” I stood. “No more protests. You’ll insult my Venetian honor if you don’t come,” I added, smiling.

“Well, since you put it that way—” He laughed. “Do you mind if we stop by the cathedral for a moment on the way out?” He took a book off his desk. “I want to return this to the archivist.”

“As long as we’re quick about it,” I said. “I’m famished.”

I helped him into his thin, worn cloak and followed him out of the office. We slowly made our way down the stairs. In the small lobby, I held the heavy door for him, and followed him out into the gray, warm afternoon.

* * *

The dark, bulky north tower of the cathedral hovered over the busy side plaza. The tower was much shorter than the ornate, elegant tower on the south side of the building. Legend had it that when the church decided to erect the second tower in the fifteenth century, the master builder had sold his soul to the devil to ensure the success of the project, and one day, while the man was high on the scaffolding, he uttered a holy name, angering his evil patron, who caused the scaffold to fall to the ground, taking the unfortunate builder with it. The tower had never been completed.

We waited as several carriages trundled by, and then crossed to the portico. To our left, several yards down the exterior wall of the cathedral, stood the old Capistran Chancel, a Gothic stone pulpit where Saint Johannes Capistrano, a Franciscan monk, had raised a crusade against the Turks in 1456. Fifty years ago, the Franciscans had erected a statue to commemorate the saint, who had died after defeating the Turks in Belgrade. The order’s own founder, Saint Francis, stood beneath a richly wrought golden sunburst, his feet trampling the body of a dead Turk.

Two cathedral workmen stood atop rickety ladders, removing the black funeral bunting from the tall north doors. Alois and I ducked around a long piece of swaying fabric and stepped into the vestibule. Felix Urbanek, one of the priests, came to greet us.

“Father Bayer, Signor Da Ponte. How good to see you both,” he said. He turned to Alois. “Have you come for the meeting about funding the new parishes, Father?”

“No, we just stopped in so that I could return this book to the archives,” Alois said.

“Careful, Fathers!” a workman shouted from behind us. His colleague had climbed to the very top of his ladder, which teetered precariously as he tried to reach the highest swath of bunting. We moved deeper into the vestibule.

Urbanek shook his head. He was a homely man, with froglike features and a sallow complexion. His bright, intelligent eyes seemed to belong to another face. “It’s taking them all day to clean up after that funeral. Did either of you attend?”

Alois and I shook our heads.

“You missed quite a show. There was much beating of the breasts over the death of the great man.”

“The general was a war hero,” Alois said quietly. “The country owed him a debt.”

“He was merely doing his duty, as we all are, Father,” Urbanek said. “He was generously rewarded for his service—a title, several fine houses, a large pension. What about all of those who fought under him, the men who never came home from the wars?” He gestured toward the bunting. “Where is their glory? I’m not the only one in Vienna who feels—”

Alois opened his mouth to speak. “How did he die?” I asked, hoping to head off an argument between the two priests.

“A seizure of some sort, I believe,” Urbanek said. “It was sudden.” He turned back to Alois. “I’m glad you are here, Father,” he said. “I am starting a committee to help the poor children who have lost their fathers in the current siege.” He sighed. “Already there have been too many deaths. It would be a great help to me if you would agree to chair the meetings. I’m busy with a lot of other things right now.”

Alois hesitated, and shook his head. “That’s a job for an active priest, someone younger and more energetic than I, I’m afraid,” he said.

Urbanek pursed his lips. “You cannot find the energy to help war orphans?”

“No, you misunderstand me,” Alois said. “It is just that I—”

Urbanek waved his hand. “Never mind, Father Bayer. I’ll find someone else to do it. If you’ll excuse me, I’ll bid you good day.” He nodded at me and turned away, heading toward the south transept.

Alois sighed. “He’s always trying to recruit me for his latest committee,” he said. “I’ve done my share here, Lorenzo. I’m tired. I just want to spend my last years with my books. Is that so bad?”

I shook my head. “No, my friend. In fact, I wish I were able to join you.” We laughed. Alois excused himself and ascended the stairway that led to the upper offices and archive. I walked onto the main floor of the cathedral. To my left, past the expansive choir, lay the elaborate high altar with its marble statues of bishops and saints. I turned my back on it and wandered over to the Gothic sandstone pulpit sculpted by Anton Pilgram in the late fifteenth century. The pulpit resembled a giant wine cup set against a large pillar. The bowl of the cup was made of four blocks of sandstone carved to resemble oriel windows, from which figures of the four fathers of the church—Saint Ambrose, Saint Jerome, Saint Gregory, and Saint Augustine—presided over the nave of the cathedral. A stone stairway curved around the pillar, its banister strewn with intricate carvings of frogs, snakes, and lizards. I had heard that the sculptor had hidden a self-portrait beneath the stairway. I ducked my head and leaned in to find it.

“Lorenzo, is that you?” A voice sounded behind me. I turned to see a dark-haired priest with a wide, crooked smile extending his hand to me. A second cleric, whom I did not recognize, stood behind him.

“Maximilian,” I said, shaking his hand. “It is good to see you. How is your work coming?” Maximilian Krause had been a lawyer before taking holy orders, and was an expert on the writings of Ludovico Muratori, a modern church reformer. I often ran into him in various bookshops in the city.

“Very well,” he replied. He gestured to the man behind him, who stepped forward. “Father Dauer, have you met Lorenzo Da Ponte? He is the poet at the Court Theater. Lorenzo, this is Hieronymus Dauer. He’s just joined the staff here.”

As I shook hands with Dauer, I studied his face. He looked like no priest I had ever seen; instead, he resembled one of the heroes of the novels the ladies had taken to reading lately, with wavy chestnut hair; a long, aristocratic nose; and a heart-shaped mouth. His gold-green eyes considered me and dismissed me with a blink.

We strolled down the nave toward the great front portal.

“Father Dauer comes to us from the abbey at Melk,” Krause said. “He was rising in the ranks there, but our provost stole him away to help manage the cathedral. Now that the state is so involved in church affairs, we needed someone with his political skills and talents.”

Dauer gave a satisfied smile at his fellow priest’s praise.

“You two have something in common,” Krause continued.

Dauer arched a delicate brow.

“You both have lived in Venice.”

“Were you born in Venice?” I asked Dauer.

He shook his head. “I was born here,” he replied. “But I spent my childhood and teenage years there. My father was attached to the Austrian embassy.”

“Lorenzo is a native,” Krause explained. “We are lucky that he has chosen to live and work here.”

Now it was my turn to look pleased at the compliment. I bit off the correction I wished to make to Krause’s statement. I would much prefer to be back in Venice, my beloved home, instead of here in Vienna. But I was no longer welcome there.

“Excuse me, please, Fathers,” a small voice said. A girl of about sixteen, dressed in an elegant satin dress festooned with bows, the neck cut low as was the latest fashion, was attempting to maneuver her way around the three of us. We moved to let her pass. She smiled gratefully and entered a small chapel to our right.

Dauer stared after her. “Look at her,” he hissed. “Dressed like a common prostitute to light a holy candle. Why does her father let her out of the house wearing that dress?” He shook his head. “I must confess, my friends, that I am amazed at some of the behavior I’ve witnessed here in the city. The moral laxness—I’ve never seen anything like it.” His eyes narrowed. “It’s due to the emperor’s reforms, I believe. There are no longer any rules about how to behave properly.” He gestured toward the young woman, who had pushed aside her skirts and was kneeling before the altar in the chapel. “That is the result.”

Although I never would criticize my Caesar aloud, I agreed with Dauer’s assessment. Over the last seven years, the emperor had attempted to apply the modern ideas of the French philosophes to Viennese society. He had ordered equal treatment for all the social classes in matters of taxation and criminal punishment; had modernized medieval church practices; and had built new schools and hospitals. But instead of the society he had aimed to create—one based on freedom and reason—it seemed to me that the emperor’s efforts had had the opposite effect. Instead of acting for the greater good, everyone these days did whatever they wanted, with no concern for the well-being of their neighbors, and no consideration of propriety.

“The result of what?” Alois joined us.

“Father Dauer was commenting on the young lady’s attire,” Krause explained, nodding toward the chapel, where the young woman had stood and was now lighting a candle.

“I’ll speak to her,” Dauer said, turning toward the chapel.

Alois placed his hand on the new priest’s arm. “I would not advise it,” he said gently. “You will not make friends that way, my son. Her father is the government minister who oversees the cathedral’s treasury.”

Dauer stiffened. “You are probably right, Father Bayer,” he said. “I appreciate your guidance.”

“Let me be, you cruel man!” a woman’s voice cried from behind us. A tall, slender young woman, shrouded in black satin and velvet, her face covered by a dark veil, rushed out of the Chapel of the Cross. She was followed by a much shorter, thick-set man with light hair. He took her arm.

“My love, please. Listen to me,” he said.

She shrugged off his hold. “I want to die too! Oh, my poor father! Can you really be dead? How could you have left me?”

All four of us gaped at her.

The young woman clutched her companion’s arm. “Swear to me! Swear to me that you will do something! Promise me you will avenge his blood!”

Dauer turned to me. “I see my presence is required, gentlemen. Signor Da Ponte, it was a pleasure meeting you.” He hurried over to the couple and murmured a few words to the young woman. She collapsed in his arms, sobbing. Dauer gently led her back into the chapel. The light-haired man followed.

“Christiane Albrechts,” Alois said. “The late general’s daughter. The man is her fiancé, Count Richard Benda. Father Dauer has just been appointed her confessor.”

“You know everyone, Father Bayer,” Krause said.

“I was her confessor years ago, when she was ten years old,” Alois explained. “Her mother had just died. Of course, her father was often away. And like most men, he had wished for a son. She was a lonely child, perhaps too serious for her own good. When the general was home, he managed her education. I thought his choices inappropriate for a young lady. I approved of the books he encouraged her to read, but he also taught her to hunt and ride astride.” He sighed. “It was a sad time. The two of them, alone in the palace on the Freyung, she pining for her mother, he for the son he never had. But she has grown to become a lovely woman. I was happy to hear of her engagement to Count Benda. He is a good man. He’ll do his best to make her happy.”

We stood quietly for a moment.

“While you are here, Father Bayer, I would like to ask a favor,” Krause said. “I’d be honored if you would read my latest article and give me your thoughts.”

“More of your natural religion ideas, Maximilian?” Alois asked, his eyes twinkling.

Krause laughed. “If you are referring to the idea that religious belief should be instilled in our flock through rational discourse rather than medieval mumbo jumbo, well then, I would say yes, that is my topic.”

“I agree with you that many of the superstitious activities the church encouraged in the past should be abolished,” Alois said. “Worshiping the icons, dressing the statues of the saints and parading them around the city—everyone knows those practices are ridiculous. But if you are arguing that we should not teach about the existence of Heaven and Hell, there is where we part ways.”

“But surely you don’t believe that we should lead people to God by using fear of retribution and threats of burning in Hell,” Krause protested. “That flies in the face of all modern church philosophy.”

I stifled a yawn.

“No, no. Not that,” Alois replied. “I just worry where all this new thinking will lead, that is all. If we take your theories to their logical ends, the laity might question whether the church is necessary at all. That is my fear.”

I coughed.

“Yet you support the emperor’s reform of the church, Father Bayer, do you not?” Krause persisted. “You must admit, the cathedral has changed for the better since Joseph took away control of the church from Rome.” He looked at me. “You’re a priest, Lorenzo. What do you think?”

I smiled. “I think it’s time for dinner.”

The priests laughed. “Send your article over to my office, Maximilian,” Alois said. “I’d be happy to read it.” We said our good-byes to Krause and headed outside.

* * *

Dusk was falling as I made my way home after a pleasant afternoon. We had tried the new catering shop near the Greek church, and the food had been tasty and plentiful. After the waiter had cleared away the dishes, we directed our attention to finishing the bottle of wine I had ordered. Our wide-ranging discussion eventually turned to the cathedral.

“These new men!” Alois said. “Maximilian, spouting all the new philosophies, and now Dauer, with his political acumen. I can no longer keep up with them. I’m happy to be retired.”

“There are a lot of new ideas floating around this city,” I agreed.

“But enough of that,” Alois said. “Tell me. What are you working on now?”

“Mozart and I are modifying Don Giovanni for the premiere on May seventh,” I told him.

“The old Don Juan farce.” Alois laughed. “People never tire of that story.” Don Giovanni, like many other operas and plays that had come before mine, was based on the Don Juan legend, the story of a noted libertine who is dragged to Hell by the ghost of a father whose daughter he had seduced.

“I hope the public here in Vienna is not tired of it,” I said.

“I’m certain they won’t be,” Alois said. He reached over and patted my hand. “You told me it was a hit in Prague last fall. It will be successful here, you’ll see. Tell me, what kind of changes are you making?”

“Well, it is always necessary to change some of the arias to suit the talents of the new cast. Sometimes a singer isn’t comfortable with an aria that hasn’t been tailored to his or her particular voice. Wolfgang prides himself on writing music to suit each performer. He calls it ‘fitting the costume to the figure.’”

Alois smiled.

“And of course Vienna is a much more sophisticated city than Prague,” I continued. “So we might have to add some scenes to appeal to the tastes here.”

“All that must take a long time,” Alois said.

“We’ll soon know how much work there’ll be. We’ve been working through the Prague libretto and score with the cast here, and we’ll finish that tomorrow.”

“What else are you doing?” my friend asked.

“I’m setting aside time to write a bit of poetry,” I answered. “I’m thinking of having a small collection published.”

“That’s wonderful, Lorenzo! I’d love to read some of them.”

“I’d be honored if you did. I’ll bring them by your office in a day or two.” We chatted about books for a while, enjoying our comfortable companionship, and did not notice the hours passing until the owner of the catering shop finally shooed us away. As I paid the bill, I remembered the pallet on the floor of Alois’s office, and considered offering to help him pay for a room at my own lodgings. But I bit my tongue for fear of embarrassing him.

Now I was heading to my lodging house, through the great Stuben gate cut into the medieval battlements of the city, and over the wide bridge that crossed the glacis, the sloped, grassy field designed to deny cover to an approaching enemy. Like most Viennese, I would prefer to live in the city, but lodgings are much less expensive out in the suburbs. My father still needed my help educating my stepbrothers back in Ceneda, so I tried to cut my expenses so that I could regularly send him funds. I have a long walk to and from my office every day, but I try to view my situation as an advantage. I’ve been so busy lately, my walk to and from work is all the fresh air I get.

The evening was as warm as the day had been, and I carried my cloak over my arm as I walked across the dusty, broad path that ran parallel to the city walls and made my way over another, smaller bridge that spanned the Vienna River. Moments later, I turned into my street. I had to admit that it was pleasant out here. Small, neat houses lined both sides of the street, and a strip of land planted with linden saplings ran down its center. Shrieks of girlish laughter greeted me as I approac

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...