- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

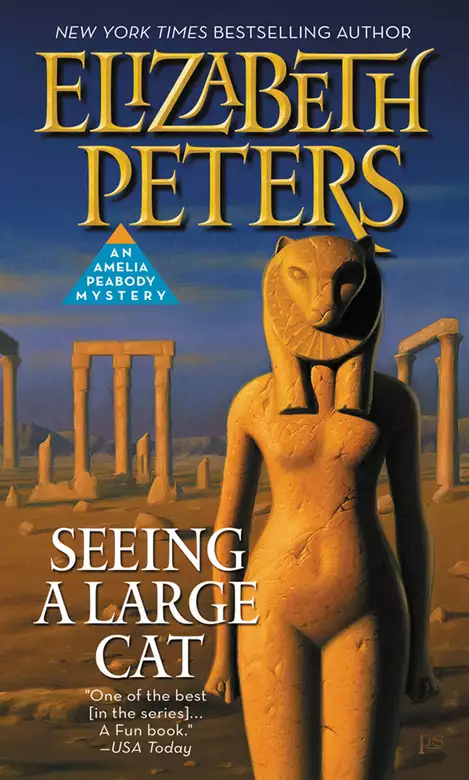

Best-selling mystery author Elizabeth Peters has captured the hearts of thousands of readers with her spunky Victorian Egyptologist, Amelia Peabody Emerson. In Seeing a Large Cat, Amelia must ensnare a modern-day killer, a bogus spiritualist, and a predatory debutante in the awesome Valley of the Kings. Someone is sending ominous messages: “Stay away from tomb Twenty-A!” Intrigued, parasol-wielding Amelia won’t rest until she finds the forbidden burial site. But when the excavation yields an unusual mummy, she suddenly must protect both her family and the macabre discovery. Her Ph.D. in Egyptology enables Elizabeth Peters to portray a lavishly detailed turn-of-the-century Egypt in her lively tale of crisp wit and shivery suspense. The spirited cast including Amelia, her eccentric family, and an array of international characters bursts into life with Barbara Rosenblat’s brilliant narration.

Release date: November 29, 2009

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Seeing a Large Cat

Elizabeth Peters

British Empire.”

—Boston Globe

“This delightful, turn-of-the-century archeologist who goes familiarly by the name of ‘Peabody’ is a joy as she journeys once

again to Egypt.”

—Denver Post

“I just adore the woman and her writing… another delightful adventure.”

—Judith Kreiner, Washington Times

“All of you Amelia Peabody fans can rejoice. She has returned as fascinating and adventurous (and funny) as ever. Enjoy!”

—Mystery News

“An intricate story line… a fun story. It’s well worth looking up the other books in the series.”

—USA Today

“Essential reading from a pro.”

—Library Journal

“The plot is fast-paced, conversations sizzle, and the entire family is fascinating.”

—Oakland Press (CA)

“My-0 Mummy, you’ll enjoy this one!”

—Bookviews

“Mystery, intrigue, and death on the Nile… intertwined with psychics, the spirits of ancient princesses, and fakirs of all

sorts.”

—St. Petersburg Times

“Terrifically funny, believable, turn-of-the-century characters.”

—Memphis Commercial Appeal

“The exotic atmosphere Peters creates provides much of the reader’s pleasure.”

—Mary Higgins Clark Mystery Magazine

“Another enticing Peabody mystery… well-plotted, complete with surprises, and the ending will leave readers looking forward

to the next installment in the series.”

—Knoxville News-Sentinel

“Good choice for a weekend read.”

—Baton Rouge Magazine

“Though there’s plenty of action under that broiling, turn-of-the-century Egyptian sun… the appeal is more personal— it’s

the welcome and invigorating visit with the extraordinary Amelia herself…. What makes SEEING A LARGE CAT unique in the Peabody

chronicles, however, is its increased emphasis on the behind-the-scenes activities of the family youngsters.”

—Anniston Star (AL)

“A great historical mystery that fans will love due to the exciting story line and great protagonists. Amelia and her brood

are wonderful characters, who, as they age, feel like old family friends. Elizabeth Peters… knows how to bring alive a bygone

era.”

—InternetBookwatch

“As much fun as a mystery can be and a sparkling new volume of Amelia’s life…. Peters has carved a special niche in the genre

which some may imitate, but none may master.”

—Salisbury Post (NC)

“Whip-smart and satisfying…with great warmth, style, and wit…. Elizabeth Peters’s fat, clever mysteries make a perfect summer

choice.”

—London Free Press (Ontario)

“Fast paced, warm spirited, and just plain fun.”

—St. Paul Pioneer Press

“Peters’s mystery series is such delicious fun…. SEEING A LARGE CAT is up to her usual high standards.”

—Winston-Salem Journal

“No one is better at juggling torches while dancing on a high wire than Elizabeth Peters.”

—Chicago Tribune

“This author never fails to entertain.”

—Cleveland Plain Dealer

“A writer so popular that the library has to keep her books under lock and key.”

—Washington Post Book World

Husbands do not care to be contradicted. Indeed, I do not know anyone who does.

Really,” I said, “Cairo is becoming overrun with tourists these days—and many of them no better than they should be! I am sorry

to see so fine a hotel as Shepheard’s allowing those male persons to hang about the entrance making eyes at the lady guests.

Their behavior is absolutely scandalous.”

My husband removed his pipe from his mouth. “The behavior of the dragomen or that of the lady guests? After all, Amelia, this

is the twentieth century, and I have often heard you disparage the rigid code of morality insisted upon by Her late Majesty.”

“The century is only three years old, Emerson. I have always been a firm believer in equal rights of all kinds, but some of

them are of the sort that should only be pursued in private.”

We were having tea on the famous terrace of Shepheard’s Hotel. The bright November sunlight was only slightly dimmed by the

clouds of dust thrown up by the wheels of vehicles and the hooves of donkeys and camels passing along Shari’a Kamel. A pair

of giant Montenegrin doormen uniformed

in scarlet and white, with pistols thrust through their sashes, were only moderately successful in protecting approaching

guests from the importunities of the sellers of fly-whisks, fake scarabs, postal cards, flowers, and figs—and from the dragomen.

Independent tourists often hired one of these individuals to make their travel arrangements and supervise their servants.

All of them spoke one or more European languages—after a fashion—and they took great pride in their appearance. Elegant galabeeyahs

and intricately wound turbans, or becoming head-cloths of the sort worn by the Beduin, gave them a romantic look that could

not but appeal to foreign visitors—especially, from what I had heard, female visitors.

I watched a couple descend from their carriage and approach the stairs. They could only be English; the gentleman sported

a monocle and a gold-headed cane, with which he swiped irritably at the ragged merchants crowding around him. The lady’s lips

were pursed and her nose was high in the air, but as she passed one of the dragomen she gave him a quick glance from under

the brim of her flower-trimmed hat and nodded emphatically. He raised his fingers to his bearded lips and smiled at her. It

was clear to me, if not to the lady’s oblivious husband, that an assignation had been made or confirmed.

“One can hardly blame the ladies for preferring a muscular, well-set-up chap like that one to your average English husband,”

said Emerson, who had also observed this exchange. “That fellow has all the animation of a walking obelisk. Imagine what he

is like in—”

“Emerson!” I exclaimed.

Emerson gave me a broad, unrepentant grin and a look that reminded me—if any reminder had been required—that he is not an

average English husband in that or in any other way. Emerson excels in his chosen profession of Egyptology as in his role

of devoted spouse. To my fond eyes he looked exactly as he had looked on that long past day when I encountered him

in a tomb at Amarna—thick dark hair, blazing blue eyes, a frame as muscular and imposing as that of the dragoman—except for

the beard he had eschewed at my request. Its removal had revealed Emerson’s strong chin and the dimple or cleft in that chin:

a feature that gives his handsome countenance additional distinction. His smile and his intense azure gaze softened me as

they always do; but the subject was not one I wished him to pursue in the presence of our adopted daughter (even if I had

introduced it myself).

“She has good taste, Aunt Amelia,” Nefret said. “He is the best looking of the lot, don’t you think?”

When I looked at her I found myself in some sympathy with the horrid Muslim custom of swathing females from head to toe in

black veils. She was a remarkably beautiful girl, with red-gold hair and eyes the color of forget-me-nots. I could have dealt

with the inevitable consequences of her looks if she had been a properly brought up young English girl, but she had spent

the first thirteen years of her life in a remote oasis in the Nubian desert, where she had, not surprisingly, acquired some

peculiar notions. We had rescued her and restored her to her inheritance,

*

and she was dear to us as any daughter. I would not have objected to her peculiar notions quite so much if she had not expressed

them so publicly!

“Yes,” she went on musingly, “one can understand the appeal of those fellows, so dashing and romantic in their robes and turbans—especially

to proper, well-behaved ladies who have led proper, boring lives.”

Emerson seldom listens to anything unconnected with Egyptology, his profession and his major passion. However, certain experiences

of the past few years had taught him he had better take notice of what Nefret said.

“Romantic be damned,” he grunted, taking the pipe from his mouth. “They are only interested in the money and—er—

other favors given them by those fool females. You have better sense than to be interested in such people, Nefret. I trust

you have not found your life proper and boring?”

“With you and Aunt Amelia?” She laughed, throwing up her arms and lifting her face to the sun in a burst of exuberance. “It

has been wonderful! Excavating in Egypt every winter, learning new things, always in the company of those dearest to me—you

and Aunt Amelia, Ramses and David, and the cat Bastet and—”

“Where the devil is he?” Emerson took out his watch and examined it, scowling. “He ought to have been here two hours ago.”

He was referring, not to the cat Bastet, but to our son, Ramses, whom we had not seen for six months. At the end of the previous

year’s excavation season, I had finally yielded to the entreaties of our friend Sheikh Mohammed. “Let him come to me,” the

innocent old man had insisted. “I will teach him to ride and shoot and become a leader of men.”

The agenda struck me as somewhat unusual, and in the case of Ramses, alarming. Ramses would reach his sixteenth birthday that

summer and was, by Muslim standards, a grown man. Those standards, I hardly need say, were not mine. Raising Ramses had converted

me to a belief in guardian angels; only supernatural intervention could explain how he had got to his present age without

killing himself or being murdered by one of the innumerable people he had offended. In my opinion what he required was to

be civilized, not encouraged to develop uncivilized skills at which he was already only too adept. As for the idea of Ramses

leading others to follow in his footsteps… My mind reeled.

However, my objections were overruled by Ramses and his father. My only consolation was that Ramses’s friend David was to

accompany him. I hoped that this Egyptian lad, who had been virtually adopted by Emerson’s younger brother and his wife, would

be able to prevent Ramses from killing himself or wrecking the camp.

The most surprising thing of all was that I rather missed the little chap. At first I enjoyed the peace and quiet, but after

a while it became boring. No muffled explosions from Ramses’s room, no screams from new housemaids who had happened upon one

of his mummified mice, no visits from enraged neighbors complaining that Ramses had ruined their hunting by making off with

the fox, no arguments with Nefret….

Two men pushed through the crowd and approached the terrace. They were both tall and broad-shouldered, but there the resemblance

ended. One was a nice-looking young gentleman wearing a well-cut tweed suit and carrying a walking stick. He had obviously

been in Egypt for some time, since his face was tanned to a handsome walnut brown. His companion wore robes of snowy white

and a Beduin headdress that shadowed features of typical Arab form—heavy dark brows, a prominent hawklike nose, and thin lips

framed by a rakish black mustache.

One of the giant guards stepped forward as if to question them. A gesture from the Arab made him step back, staring, and the

two men proceeded to mount the stairs.

“Well!” I exclaimed. “I don’t know what Shepheard’s is coming to. They ought not let the dragomen—”

But my sentence was never completed. With a scream of delight Nefret jumped up from her chair and ran, her hat flying from

her head, to throw herself at the Beduin. For a few moments the only visible part of her was her red-gold head, as his flowing

sleeves wrapped round her slim body.

Emerson, close on Nefret’s heels, pulled her away from the Beduin and began vigorously wringing the latter’s hand. Nefret

turned to the other young man. He held out his hand. Laughing, she pushed it away and hugged him as she had done Ramses.

Ramses? Little chap? Ramses had never been a normal little boy, but there had been times (usually when he was asleep) when

he had appeared normal. The sleeping cherub with his mop of sable curls and his little bare feet protruding innocently

from under the hem of his white nightgown had become this—this male person with a mustache! I supposed the transformation

could not have occurred overnight. In fact, now that I thought about it, I recalled that he had been growing taller year by

year, in the usual way. He was almost as tall as his father now, a good six feet in height. I could have dealt with that.

But the mustache…

Trusting that my paralysis would be taken for dignified reticence, I remained in my chair. Emerson had so forgot his usual

British reserve as to put an arm round his son’s shoulders in order to lead him to me. Ramses’s naturally swarthy complexion

had been darkened by sun and wind to a shade even browner than that of his young Egyptian friend, and his countenance was

as unexpressive as it always was. He bent over me and gave me a dutiful kiss on the cheek.

“Good afternoon, Mother. You are looking well.”

“I can’t say the same for you,” I replied. “That mustache—”

“Not now, Peabody,” Emerson interrupted. “Good Gad, this is supposed to be a celebration. The important thing is that they

are both back, safe and sound.”

“And cursed late,” said Nefret, settling herself in the chair David held for her. One of the waiters handed her her hat; she

clapped it carelessly onto her head and went on, “Did you miss the early train?”

“No, not at all,” David replied. His English was now almost as pure as my own; only when he was excited did a trace of his

native Arabic creep in. “The Professor and Aunt Amelia may be getting complaints from some of the passengers, though; the

tribe gave us a proper send-off, galloping alongside the train shooting off their rifles. The other people in our compartment

fell cowering to the floor and one lady went into hysterics.”

Nefret’s eyes shone with laughter. “I wish I could have been there. It is so damned—excuse me, Aunt Amelia—it is so unfair!

If I had been a boy I could have gone with you. I suppose

I wouldn’t have enjoyed spending six months as a Beduin female, though.”

“You would not have found it as confining as you may think,” David said. “I was surprised at how much freedom the women of

the tribe are allowed; in their own camp they do not veil themselves, and they express their opinions with a candor that Aunt

Amelia would approve. Though she might not approve of the way in which young unmarried girls express their interest in—” He

broke off abruptly, with a sheepish glance at Ramses. The latter’s countenance was as imperturbable as ever, but it was not

difficult to deduce that he had signaled David—perhaps by kicking him under the table—to refrain from finishing the sentence.

“Well, well,” said Emerson. “So why were you so late?”

“We stopped at Meyer and Company, on the Muski,” Ramses explained. “David wanted a new suit.”

David smiled self-consciously. “Honestly, Aunt Amelia, neither of us has a respectable garment left to our names. I didn’t

want to embarrass you by appearing improperly dressed.”

“Hmph,” I said, looking at my son, who looked blandly back at me.

“As if any of us would care!” Nefret exclaimed. “To keep us waiting, fidgeting and worrying for hours, over something so silly!”

“Were you?” Ramses asked.

“Fidgeting and worrying? Not I! It was the Professor and Aunt Amelia….” But her scowl metamorphosed into a dazzling smile;

with the graceful, impulsive friendliness that was so integral a part of her nature she held out her hands, one to each lad.

“If you must know, I have missed you desperately. And now I see I will have to play chaperone; you are both grown so tall

and handsome all the little girls will be making eyes at you.”

Ramses, who had enclosed her hand in his, dropped it as if it had become red-hot. “Little girls?”

How often, dear Reader, is a small, seemingly insignificant incident the start of a train of events that builds inexorably

to a tragic climax! If Ramses had not chosen to appear in that dashing costume; if Nefret’s impulsive welcome had not drawn

all eyes to them; if Ramses had not raised his voice in indignant baritone outcry… The consequences would draw us into one

of the most baffling and bizarre criminal cases we had ever investigated.

On the other hand, it is possible that the same thing would have happened anyhow.

Ramses got himself under control and Nefret wisely refrained from further provocation. She and Ramses were really the best

of chums—when they were not squabbling like spoiled infants—and a request from her soothed his temper.

“Can you persuade M. Maspero to let me examine some of the mummies in the museum?” she demanded. “He has been putting me off

for days. One would think I had proposed something illegal or shocking.”

“He probably was shocked,” said David, smiling. “You can’t blame him, Nefret; he thinks of ladies as delicate and squeamish.”

“I will blame him if I like. He lets Aunt Amelia do anything she wants.”

“He’s used to her,” said Ramses. “We will go there together, you and I and David. He can’t resist all three of us. What particular

mummies have you in mind?”

“Most particularly, the one we found in Tetisheri’s tomb three years ago.”

“Good heavens,” David said, appearing a trifle shocked himself. “I can see why Maspero… Er, that is, you must admit, Nefret,

it was a particularly disgusting mummy. Unwrapped, unnamed, bound hand and foot—”

“Buried alive,” Nefret finished. She planted both elbows on the table and leaned forward. A lock of gold-red hair had escaped

from her upswept coiffure and curled distractingly across her temple; her cheeks were flushed with excitement and her blue

eyes shone. An observer might have supposed she was discussing fashions or flirtations. “Or so we assumed. I want to have

another look. You see, while you were gadding about in the desert, I was improving my education. I took a course in anatomy

last summer.”

“At the London School of Medicine for Women?” Ramses asked interestedly.

“Where else?” Nefret’s blue eyes flashed. “It is the only institution in our enlightened nation where a mere female may receive

medical training.”

“But is that still strictly true?” Ramses persisted. “I was under the impression that Edinburgh, Glasgow, and even the University

of London—”

“Confound you, Ramses, you are always destroying my fiery rhetoric with your pedantic insistence on detail!”

“I apologize,” Ramses said meekly. “Your point—the unfair discrimination against females in all fields of higher education—is

unaltered by the few exceptions I have mentioned, and the difficulties of actually qualifying to practice medicine are almost

as great, I believe, as they were fifty years ago. I admire you, Nefret, for persisting under such adverse conditions. Let

me assure you I am one hundred percent on your side and that of the other ladies.”

She laughed at him and squeezed his hand. “I know you are, Ramses, dear. I was only teasing. Dr. Aldrich-Blake herself allowed

me to attend her lectures! She feels I have an aptitude…”

Pleased to see them in amicable accord, I was following the conversation so intently I was unaware of the young lady’s approach

until she spoke—not to any of us but to her companion. It was impossible to avoid hearing her; they had stopped next to our

table and her voice was piercingly shrill.

“I told you to leave me alone!”

I had not observed her approach, but Ramses must have done. He was instantly on his feet. Removing his khafiya—a courtesy

he had not extended to the female members of his family—he said, “May I be of assistance?”

Hands fluttering in appeal, the girl turned to him. “Oh, thank you,” she breathed. “Please—can you make him go away?”

Her companion gaped at her. A long jaw and crooked nose marred an otherwise pleasant face. He was clean-shaven, with gray

eyes and hair of an indeterminate tannish color. “See here, Dolly,” he began, and put out his hand.

I don’t believe he meant to take hold of her, but I was not to find out. Ramses caught his wrist. The movement was apparently

effortless, the grip without apparent pressure, but the young fellow squawked and buckled at the knees.

“Good Gad, Ramses,” I exclaimed. “Let him go at once.”

“Certainly,” said Ramses. He released his hold, but he must have done something else I did not see, for the unfortunate youth

sat down with a thump.

Humiliation is a more effective weapon against the young than physical pain. The youth got to his feet and retreated—but not

before he had given Ramses a threatening look.

He held Ramses accountable, of course. Being a man, he was too obtuse to realize, as did I, that the girl had deliberately

provoked the incident. Her little hands now rested on Ramses’s arm and she had tipped her head back in order that she might

gaze admiringly into his eyes. A mass of curls so fair as to be almost white framed her face, and she was dressed in the height

of fashion. I guessed her to be no more than twenty, possibly less. The young ladies of America—for her accent had betrayed

her nationality—are much more sophisticated and more indulged than their English counterparts. That this young lady had a

wealthy parent I did not doubt. She positively glittered with diamonds—most inappropriate for the time of day and her apparent

age.

I said, “Allow me to present my son, Miss Bellingham. Ramses, if Miss Bellingham is feeling faint after her terrible ordeal,

I suggest you offer her a chair.”

“Thank you, ma’am, I’m just fine now.” She turned her dimpled smile on me. Hers was a pretty face, with no distinctive characteristics

except a pair of very big, very melting brown eyes that formed a striking contrast to her silvery-fair hair. “I know you,

of course, Mrs. Emerson. You and your husband are the talk of Cairo. But how do you know the name of an insignificant little

person like myself?”

“We met your father last week,” I replied. Emerson growled, but did not comment. “He mentioned his daughter and referred to

her as ‘Dolly.’ A nickname, I presume?”

“Like ‘Ramses,’” said the insignificant little person, offering him a gloved hand. “It is a pleasure to meet you, Mr. Emerson.

I had heard of you, too, but I had no idea you were so… Thank you. I sure appreciate your gallantry.”

“Won’t you join us?” I asked, as courtesy demanded. “And allow me to introduce Miss Forth and Mr. Todros.”

Her eyes passed over David as if he had been invisible and rested, briefly, on Nefret’s stony countenance.

“How do you do. I am afraid I cannot stay. There is Daddy now—late as always, the dreadful man! He will fuss at me if I keep

him waiting.”

After giving Ramses a last languishing look she tripped away.

The man who awaited her near the top of the stairs wore an old-fashioned frock coat and snowy stock. Since his military title,

as I had been informed, derived from service in the Southern forces during the American Civil War, he must be at least sixty

years of age, but one would have supposed him to be younger. He had the erect carriage and lean limbs of a cavalryman, and

his white hair, worn rather longer than was the fashion, shone like a silver helmet. His neatly trimmed beard and mustache

recalled photographs I had seen of General Lee,

and I supposed he had deliberately cultivated the resemblance.

However, the benevolence that beamed from the countenance of that hero of the Confederacy was not apparent on the face of

the Colonel. He must have observed the encounter, or part of it; he shot us a long look before drawing the girl’s arm through

his and leading her away.

“Interesting,” said Ramses, resuming his chair. “From your reaction to the mention of his name I gather your earlier meeting

with Colonel Bellingham was not altogether friendly, Father. What precisely did he do to provoke your ire?”

Emerson said forcibly, “The fellow had the audacity to offer me a position as his hired lackey. He is another of those wealthy

dilettantes who are amusing themselves by pretending to be archaeologists.”

“Now, Emerson, you know that was not his real object,” I said. “His offer to finance our work—an error on his part, I confess—was

in the nature of a bribe. What really concerned him was—”

“Amelia,” said Emerson, breathing heavily through his nose. “I told you I refuse to discuss the subject. Certainly not in

front of the children.”

“Pas devant les enfants?” Nefret inquired ironically. “Professor, darling, we are no longer ‘enfants,’ and I’ll wager I can guess what the Colonel wanted. A chaperone, or governess, or nursery maid for that doll-faced girl!

She certainly needs one.”

“According to the Colonel, it is a bodyguard she needs,” I said.

“Peabody!” Emerson roared.

One of the waiters dropped the tea tray he was carrying, and everyone within earshot stopped talking and turned to stare.

“It’s no use, Emerson,” I said calmly. “Nefret is not guessing; she knows what the Colonel was after, though how she knows

I am reluctant to consider. Eavesdropping—”

“Is cursed useful at times,” said Nefret. She gave Ramses a

comradely grin, and he responded with the slight curl of the lips that was his version of a smile. “Don’t scold me, Aunt Amelia,

I was not eavesdropping. I happened to be passing the saloon while you were talking with the Colonel, and I could not help

overhearing the Professor’s comments. It was not difficult to deduce from them what the subject of the conversation must be.

But I cannot believe that little ninny is in danger.”

“From whom?” Ramses asked. “Surely not the fellow who was with her?”

“I shouldn’t think so,” said Nefret. “Colonel Bellingham said he could not keep a female attendant for her; three of them

have fallen ill or been injured under mysterious circumstances. In the last case, he claimed, a carriage driver tried to seize

Dolly, and would have dragged her into the vehicle if her maid had not prevented it. He denied knowing who might have been

responsible, or why anyone would want to make off with darling little Dolly.”

“Ransom?” David suggested. “They must be wealthy; she was wearing a fortune in jewels.”

“Revenge,” said Ramses. “The Colonel may have enemies.”

“Frustrated love,” murmured Nefret, in a saccharine voice.

Emerson’s fist came down on the table. Since I had expected this would happen I was able to catch the teapot as it tottered.

“Enough,” Emerson exclaimed. “This is precisely the kind of idle, irrelevant speculation in which this family is fond of engaging—with

the sole exception of myself! I don’t give a curse whether the entire criminal population of Charleston, South Carolina, and

Cairo, Egypt, are after the girl. Even if it were not stuff and nonsense, it is none of our affair! Bodyguard, indeed. Change

the subject.”

“Of course,” Nefret said. “Ramses—how did you do that?”

“Do what?” He glanced at the slim hand she had extended. “Oh. That.”

“Show me.”

“Nefret!” I exclaimed. “A young lady should not—”

“I am surprised that you should take that attitude, Mother,” Ramses said. “I will show you too, if you like; the trick might come in useful, in view

of your habi

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...