- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

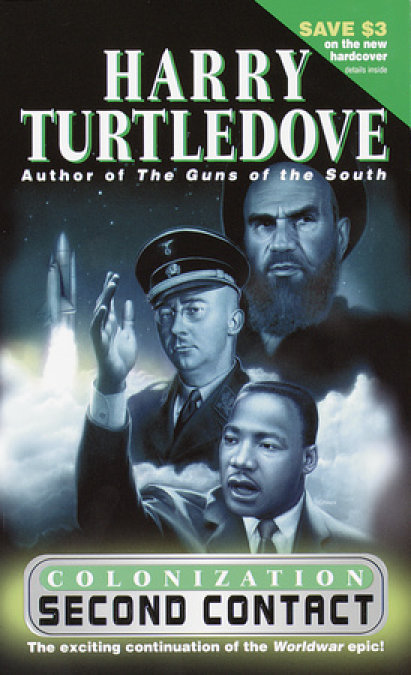

Synopsis

“[A] tour de force of speculative historical fiction. Highly recommended.”—Library Journal

In the extraordinary Worldwar tetralogy, set against the backdrop of World War II, Harry Turtledove, the “Hugo-winning master of alternate SF” (Publishers Weekly), wove an explosive saga of world powers locked in conflict against an enemy from the stars. Now he expands his magnificent epic into the volatile 1960s, when the space race is in its infancy and humanity must face its greatest challenge: alien colonization of planet Earth.

Yet even in the shadow of this inexorable foe, the United States, the Soviet Union, and Nazi Germany are unable to relinquish their hostilities and unite against a massive new wave of extraterrestrials. For all the countries of the world, this is the greatest threat of all. This time, the terrible price of defeat will be the conquest of our world, and perhaps the extinction of the human race itself.

Praise for Second Contact

“An exciting, often surprising, story that will not only delight his fans but will probably send newcomers back to the Worldwar saga.”—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“Outstanding entertainment.”—Booklist

Release date: January 8, 2002

Publisher: Ballantine Books

Print pages: 608

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Second Contact

Harry Turtledove

So had Kirel, shiplord of the 127th Emperor Hetto, the bannership of the conquest fleet. The body paint on his scaly, green-brown hide was more ornate than every other male's save only Atvar's. His mouth fell open in amusement, revealing a great many small, sharp teeth. A slight waggle to his lower jaw gave his laughter a sardonic twist.

"Once more we behold the might Tosevite warrior, eh, Exalted Fleetlord?" he said. He ended the sentence with an interrogative cough.

"Even so, Shiplord," Atvar answered. "Even so. He does not look as if he would cause us much trouble, does he?"

"By the Emperor, no," Kirel said. Both Atvar and he swiveled their turreted eyes so they looked down at the ground for a moment: a gesture of respect for the sovereign back on distant Home.

As Atvar had done so many times before, he walked around the hologram to view it from all sides. The Tosevite male was mounted on a hairy local quadruped. He wore a tunic of rather rusty chain armor, and over it a light cloth coat. A pointed iron helmet protected his braincase. Tufts of yellowish hair grew like dry grass on his scaleless, pinkish cheeks and jaw. For armament, he had a spear, a sword, a knife, and a shield with a cross painted in red on it.

A long, hissing sigh escaped Atvar. "If only it had been as easy as we thought it would be."

"Truth, Exalted Fleetlord," Kirel said. "Who would have thought the Big Uglies"—the nickname the Race used for its Tosevite subjects and neighbors—"could have changed so much in a mere sixteen hundred years?"

"No one," Atvar said. "No one at all." He used a different cough this time, one that emphasized the words preceding it. They deserved emphasis. The Race—and the Hallessi and Rabotevs, whose planets the Empire had ruled for thousands of years—changed only very slowly, only very cautiously. For the Race, one millennium was like another. After sending a probe to Tosev 3, everyone back on Home had blithely assumed the barbarians there would not have changed much by the time the conquest fleet arrived.

Never in its hundred thousand years of unified imperial history—and never in the chaotic times before, for that matter—had the Race got a larger and more unpleasant surprise. When the conquest fleet did reach Tosev 3, it found not sword-swinging savages but a highly industrialized world with several empires and not-empires battling one another for dominance.

"Even after all these years, there are times when I still feel rage that we did not completely conquer this planet," Atvar said. "But, on the other fork of the tongue, there are also times when I feel nothing but relief that we still maintain control over any part of its surface."

"I understand, Exalted Fleetlord," Kirel said.

"I know you do, Shiplord. I am glad you do," Atvar said. "But I do wonder if anyone back on Home truly understands. I have the dubious distinction of commanding the first interstellar conquest fleet in the history of the Race that did not conquer completely. That is not how I intended hatchlings to remember me."

"Conditions here were not as we anticipated them," Kirel said loyally. He'd had his chances to be disloyal, had them and not taken them. By now, Atvar was willing to believe he wouldn't. He went on, "Do you not agree that there is a certain amount of irony in the profit we have made off the Tosevites by selling them this image and others from the probe? Their own scholars desire those photographs because they have none of their own from what seems to them to be a distant and uncivilized time."

"Irony? Yes, that is one of the words I might apply to the situation—one of the politer words," Atvar said. He went back to his desk and prodded the control again. The Tosevite warrior vanished. He wished he could make all the Tosevites vanish that easily, but no such luck. He replaced the warrior's image with a map of the surface of Tosev 3.

By his standards, it was a chilly world, with too much water and not enough land. Of what land there was, the Race did not rule enough. Only the southern half of the lesser continental mass, the southwest and south of the main continental mass, and the island continent to the southeast of the main continental mass were reassuringly red on the map. The not-empires of the Americans, the Russkis, and the Deutsche all remained independent, and needed colors of their own. So did the island empires of Britain and Nippon, though both of them were shrunken remnants of what they had been when the conquest fleet came to Tosev 3.

Kirel also turned one eye toward the map, while keeping the other on Atvar. "Truly, Exalted Fleetlord, it could be worse."

"So it could," Atvar said with another sigh. "But it could also be a great deal better. It would be a great deal better if these areas here on the eastern part of the main continental mass, especially this one called China, acknowledged our rule as they should."

"I have long since concluded that the Big Uglies never do things as they should," Kirel said.

"I agree completely," the fleetlord replied. His little tailstump twitched in agitation. "But how are we to convince the fleetlord of the colonization fleet that this is the case?"

Now Kirel sighed. "I do not know. He lacks our experience with this world. Once he acquires it, he will, I am sure, come round to our way of thinking. But we must expect him to be rigid for a time."

Back on Home, rigid was a term of praise. It had been a term of praise when the conquest fleet come to Tosev 3, too. No more. Males of the Race who stayed too rigid stood not a chance of understanding the Big Uglies. By the standards of Home, the males of the conquest fleet—those who still survived—had grown dreadfully flighty.

Males ... Atvar said, "It will be good to have females in range of the scent receptors on my tongue once more. When they come into season and I smell their pheromones, I will have an excuse for not thinking about this accursed world for a while. I look forward to having the excuse, you understand, not to the breeding itself."

"Of course, Exalted Fleetlord," Kirel said primly. "You are no Big Ugly, to have such matters always on your mind."

"I should hope not!" Atvar exclaimed. Like any other member of the Race, he viewed Tosevite sexuality with a sort of horrified fascination. Intellectually, he grasped how the Big Uglies' year-round interest in mating colored every aspect of their behavior. But he had no feel for the subtleties, or indeed for what the Big Uglies no doubt viewed as broad strokes. Despite intensive research, few males of the Race did, any more than the Tosevites could understand the Race's dispassionate view of such matters.

Pshing, Atvar's adjutant, came into the chamber. One side of his body was painted in a pattern that matched the fleetlord's; the other showed his own, far lower, rank. He bent his forward sloping torso into the posture of respect and waited to be noticed.

"Speak," Atvar said. "Give forth."

"I thank you, Exalted Fleetlord," Pshing said. "I beg leave to report that the lead ships of the colonization fleet have passed within the orbit of Tosev 4, the planet the Big Uglies call Mars. Very soon now, those ships will seek to circle and land on this world."

"I am aware of this, yes." Atvar's voice was even drier than the desert surrounding the riverside city—Cairo, the local name for it was—where he made his headquarters. "Is my distinguished colleague in the colonization fleet aware that the Tosevites, for all their protestations of peaceful intent, may seek to harm his ships when they do reach Tosev 3?"

"Fleetlord Reffet continues to assure me that he is," Pshing replied. "He was quite taken aback to receive radio transmissions from the various Tosevite not-empires."

"He should not have been," Atvar said. "We have been warning him for some time of the Big Uglies' ever-increasing capacities."

Kirel said, "Exalted Fleetlord, he will have to learn by experience, as we also had to do. Let us hope his experience proves less painful than ours."

"Indeed." Atvar let out a worried hiss. His voice grew grim: "And let us hope all the Tosevites take seriously our warning to them that an attack on the colonization fleet by any of them will be construed as an attack by all of them, and that we shall do our utmost to punish all of them should any such attack occur."

"I wish we had not had to issue such a warning," Kirel said.

"So do I," Atvar replied. "But least four and perhaps five of their realms possess missile-firing undersea ships—who back on Home would have dreamt of such things?"

"Oh, I understand the problem," Kirel said. "But the general warning all but invites the Tosevites to combine against us and to reduce their conflicts among themselves."

"Diplomacy." Atvar made the word into a curse. Manuals on the subject, their data gleaned from the Race's ancient history and early conquests, suggested playing the locals off against one another. But, to Atvar and his colleagues, such concerns were but theory, and musty theory at that. The Big Uglies, divided among themselves, were expert practitioners of the art. After a negotiating session with them, Atvar always wanted to count his fingers and toes to make sure he hadn't inadvertently traded them away.

Pshing said, "When the colonists are revived from cold sleep, when they come down to Tosev 3, we will begin to turn this into a proper world of the Empire."

"I admire your confidence, Adjutant," Kirel said. Pshing crouched respectfully. Kirel went on, "I wonder what the colonists will make of us. We are hardly proper males of the Race ourselves any more—dealing with the Tosevites for so long has left us as addled as bad eggs."

"We have changed," Atvar agreed. Back on Home, that would have been a curse. Not here, though he had taken a long time to realize it. "Had we not changed, our war with the Big Uglies would have wrecked this planet, and what would the colonization fleet have done then?"

Not a single male on Tosev 3 had found an answer to that question. Atvar was sure Reffet would have no answer for it, either. But he was also sure the fleetlord of the colonization fleet would have questions of his own. Would he himself, would any male on Tosev 3, be able to find answers for them?

The pitcher windmilled into his delivery. The runner took off from first base. The batter hit a sharp ground ball to short. The shortstop gobbled it up and fired it over to first. The softball slapped Sam Yeager's mitt, beating the runner to the bag by a step and a half. The umpire had hustled up from behind home plate. "You're out!" he yelled, and threw his fist in the air.

"That's the ballgame," Yeager said happily. "Another win for the good guys." He tacked on an emphatic cough for good measure.

"Nice game, Major," the pitcher said. "A homer and a double—I guess we'll take that."

"Thanks, Eddie," Yeager said, chuckling. "I can still get around on a softball." He was in his mid-fifties, and in good shape for his mid-fifties, but he couldn't hit a baseball for beans any more. It irked him; he'd been in his eighteenth season of minor-league ball when the Lizards came, and he'd kept playing as much and as long as he could after going into the Army.

He rolled the softball toward the chicken-wire dugout in back of first base. He'd been an outfielder when he played for money, but he couldn't cover the ground out there any more, either, so nowadays he played first. He could still catch and he could still throw.

A couple of guys from the other team came over and shook his hand. They'd been playing just for the fun of playing. He'd had fun, too—he wouldn't have put on spikes if he didn't have fun—but he'd gone out there to win. Playing for money for all those years had ingrained that in him.

Up in the wooden bleachers behind the wire fence, Barbara clapped her hands along with the other wives and girlfriends. Sam doffed his cap and bowed. His wife made a face at him. That wasn't why he put the cap back on in a hurry, though. He was getting thin on top, and Southern California summer sunshine was no joke. He'd sunburned his scalp a couple of times, but he intended never, ever, to do it again.

"Head for Jose's!" Win or lose, that cry rang out after a game. Winning would make the tacos and beer even better. Sam and Barbara piled into their Buick and drove over to the restaurant. It was only a few blocks from the park.

The Buick ran smoothly and quietly. Like more and more cars every year, it burned hydrogen, not gasoline—technology borrowed from the Lizards. Sam coughed when he got stuck behind an old gas-burner that poured out great gray clouds of stinking exhaust. "Ought to be a law against those miserable things," he complained.

Barbara nodded. "They've outlived their usefulness, that's certain." She spoke with the precision of someone who'd done graduate work in English. Yeager minded his p's and q's more closely than he would have had he not been married to someone like her.

At Jose's, the team hashed over the game. Sam was ten years older than anybody else and the only one who'd ever played pro ball, so his opinions carried weight. His opinion in other areas carried weight, too; Eddie, the pitcher, said, "You deal with the Lizards all the time, Major. What's it going to be like when that big fleet gets here?"

"Can't know for sure till it does get here," Yeager answered. "If you want to know what I think, I think it'll be the biggest day since the conquest fleet came down. We're all doing our best to make sure it isn't the bloodiest day since the conquest fleet came down, too."

Eddie nodded, accepting that. Barbara raised an eyebrow—just a little, so only Sam noticed. She saw the logical flaw the young pitcher missed. If all of mankind wanted the colonization fleet to land peacefully, that would happen. But no one on this side of the Atlantic could guess what Molotov or Himmler might do till he did it—if he did it. And the Nazis and the Reds—and the Lizards—would be worrying about President Warren, too.

After Sam finished his glass of Burgermeister, Barbara said, "I don't want to rush you too much, but we did tell Jonathan we'd be home when he got back."

"Okay." Yeager got up, set a couple of bucks on the table to cover food and drink, and said his goodbyes. Everybody—including Jose from behind the counter—waved when he and Barbara took off.

They lived over in Gardena, one of the suburbs on the west side of L.A. that had burgeoned since the end of the fighting. When they got out of the car, Barbara remarked, as she often did, "Cooler here."

"It's the sea breeze," Sam answered, as he often did. Then he plucked at his flannel uniform top. "It may be cooler, but it's not that cool. I'm going to hop in the shower, is what I'm going to do."

"That would be a very good idea, I think," Barbara said. Yeager stuck out his tongue at her. They both laughed, comfortable with each other. Why not? Sam thought. They'd been together since late 1942, only a few months after the conquest fleet arrived. Had the Lizards not come, they never would have met. Sam didn't like thinking about that; Barbara was the best thing that had ever happened to him.

To keep from dwelling on might-have-beens, he hurried into the house. Photographs in the hallway that led to the bathroom marked the highlights of his career: him in dress uniform just after being promoted from sergeant to lieutenant; him weightless, wearing olive-drab undershirt and trousers, aboard an orbiting Lizard spaceship—overheated by human standards—as he helped dicker a truce after a flare-up; him in a spacesuit on the pitted surface of the moon; him in captain's uniform, standing between Robert Heinlein and Theodore Sturgeon.

He grinned at that last one, which he sometimes had to explain to guests. If he hadn't been reading the science-fiction pulps, and especially Astounding, he never would have become a specialist in Lizard-human relations. Having been overrun by fact, science fiction wasn't what it had been before the Lizards came, but it still had some readers and some writers, and he'd never been a man to renounce his roots.

He showered quickly, shaved even more quickly, and put on a pair of chinos and a yellow cotton short-sleeved sport shirt. When he got a beer from the refrigerator, Barbara gave him a piteous look, so he handed it to her and grabbed another one for himself.

He'd just taken his first sip when the door opened. "I'm home!" Jonathan called.

"We're in the kitchen," Yeager said.

Jonathan hurried in. At eighteen, he hurried everywhere. "I'm hungry," he said, and added an emphatic cough.

"Make yourself a sandwich," Barbara said crisply. "I'm your mother, not your waitress, even if you do have trouble remembering it."

"Take your tongue out of the ginger jar, Mom. I will," Jonathan said, a piece of slang that wouldn't have meant a thing before the Lizards came. He wore only shorts that closely matched his suntanned hide. Across that hide were the bright stripes and patterns of Lizard-style body paint.

"You've promoted yourself," Sam remarked. "Last week, you were a landcruiser driver, but now you're an infantry small-unit group leader—a lieutenant, more or less."

Jonathan paused with his salami sandwich half built. "The old pattern was getting worn,"he answered with a shrug. "The paints you can buy aren't nearly as good as the ones the Lizards—"

"Nearly so good," his mother broke in, precise as usual.

"Nearly so good, then," Jonathan said, and shrugged again. "They aren't, and so I washed them off and put on this new set. I like it better, I think—brighter."

"Okay." Sam shrugged, too. People his son's age took the Lizards for granted in a way he never could. The youngsters didn't know what the world had been like before the conquest fleet came. They didn't care, either, and laughed at their elders for waxing nostalgic about it. Recalling his own youth, Sam did his best to be patient. It wasn't always easy. Before he could stop himself, he asked, "Did you really have to shave your head?"

That flicked a nerve, where talk about body paint hadn't. Jonathan turned, sliding a hand over the smooth and shining dome of his skull. "Why shouldn't I?" he asked, the beginning of an angry rumble in his voice. "It's the hot thing to do these days."

Along with body paint, it made people look as much like Lizards as they could. Hot was a term of approval because the Lizards liked heat. The Lizards liked ginger, too, but that was a different story.

Sam ran a hand through his own thinning hair. "I'm going bald whether I want to or not, and I don't. I guess I have trouble understanding why anybody who's got hair would want to cut it all off."

"It's hot," Jonathan repeated, as if that explained everything. To him, no doubt, it did. His voice lost some of that belligerent edge as he realized his father wasn't insisting that he let his hair grow, only talking about it. When he didn't feel challenged, he could be rational enough.

He took an enormous bite from his sandwich. He was three or four inches taller than Sam—over six feet instead of under—and broader through the shoulders. By the way he ate, he should have been eleven feet tall and seven feet wide.

His second bite was even bigger than the first. He was still chewing when the telephone rang. "That's got to be Karen!" he said with his mouth full, and dashed away.

Barbara and Sam shared looks of mingled amusement and alarm. "In my day, girls didn't call boys like that," Barbara said. "In my day, girls didn't shave their heads, either. Go on, call me a fuddy-duddy."

"You're my fuddy-duddy," Sam said fondly. He slipped an arm around her waist and gave her a quick kiss.

"I'd better be," Barbara said. "I'm glad I am, too, because there are so many more distractions now. In my day, even if there had been body paint, girls wouldn't have been so thorough about wearing it as boys are—and if they had been, they'd have been arrested for indecent exposure."

"Things aren't the same as they used to be," Sam allowed. His eyes twinkled. "I might call that a change for the better, though."

Barbara elbowed him in the ribs. "Of course you might. That doesn't mean I have to agree with you, though. And"—she lowered her voice so Jonathan wouldn't hear—"I'm glad Karen isn't one of the ones who do."

"Well, so am I," Sam said, although with a sigh that earned him another pointed elbow. "Jonathan and his pals are a lot more used to skin than I am. I'd stare like a fool if she came over dressed—or not dressed—that way."

"And then you'd tell me you were just reading what her rank was," Barbara said. "You'd think I love you enough to believe a whopper like that. And you know what?" She poked him again. "You might even be right."

Felless had not expected to wake in weightlessness. For a moment, staring up at the fluorescent lights overhead, she wondered if something had gone wrong with the ship. Then, thinking more slowly than she should have because of the lingering effects of cold sleep, she realized how foolish that was. Had something gone wrong with the ship, she would never have awakened at all.

Two people floated into view. One, by her body paint, was a physician. The other ... Weak and scatterbrained as Felless was, she gave a startled hiss. "Exalted Fleetlord!" she exclaimed. She heard her own voice as if from far away.

Fleetlord Reffet spoke not to her but to the physician: "She recognizes me, I see. Is she capable of real work?"

"We would not have summoned you here, Exalted Fleetlord, were she incapable," the physician replied. "We understand the value of your time."

"Good," Reffet said. "That is a concept the males down on the surface of Tosev 3 seem to have a great deal of trouble grasping." He swung one of his eye turrets to bear on Felless. "Senior Researcher, are you prepared to begin your duties at once?"

"Exalted Fleetlord, I am," Felless replied. Now the voice her hearing diaphragms caught seemed more like her own. Antidotes and restoratives were routing the drugs that had kept her just this side of death on the journey from Home to Tosev 3. Curiosity grew along with bodily well-being. "May I ask why I have been awakened prematurely?"

"You may," Reffet said, and then, in an aside to the physician, "You were right. Her wits are clear." He gave his attention back to Felless. "You have been awakened because conditions on Tosev 3 are not as we anticipated they would be when we set out from Home."

That was almost as great a surprise as waking prematurely. "In what way, Exalted Fleetlord?" Felless tried to make her wits work harder. "Does this planet harbor some bacterium or virus for which we have had difficulty in finding a cure?" Such a thing hadn't happened on either Rabotev 2 or Halless 1, but remained a theoretical possibility.

"No," Reffet replied. "The difficulty lies in the natives themselves. They are more technically advanced than our probe indicated. You being the colonization fleet's leading expert on relations between the Race and other species, I judged it expedient to rouse you and put you to work before we make planetfall. If you need assistance, give us names, and we shall also wake as many of your subordinates and colleagues as you may require."

Felless tried to lever herself off the table on which she lay. Straps restrained her: a sensible precaution on the physician's part. As she fumbled with the catches, she asked, "How much more advanced were they than we expected? Enough to make the conquest significantly harder, I gather."

"Indeed." Reffet added an emphatic cough. "When the conquest fleet arrived, they were engaged in active research on jet aircraft, on guided missiles, and on nuclear fission."

"That is impossible!" Felless blurted. Then, realizing what she'd said, she added, "I beg the Exalted Fleetlord's pardon."

"Senior Researcher, I freely give it to you," Reffet replied. "When the colonization fleet began receiving data from Tosev 3, my first belief was that Atvar, the fleetlord on the conquest fleet, was playing an elaborate joke on us—jerking our tailstumps, as the saying has it. I have since been disabused of this belief. I wish I had not been, for it strikes me as far more palatable than the truth."

"But—But—" Felless knew she was stuttering, and made herself pause to gather her thoughts. "If that is true, Exalted Fleetlord, I count it something of a marvel that ... that the conquest did not fail." Such a thought would have been unimaginable back on Home. It should have been unimaginable here, too. That she'd imagined it proved it wasn't.

Reffet said, "In part, Senior Researcher, the conquest did fail. There are still unsubdued Tosevite empires—actually, the term the conquest fleet consistently uses is not-empires, which I do not altogether understand—on the surface of Tosev 3, along with areas the Race has in fact conquered. Nor have the Tosevites ceased their technical progress in the eyeblink of time since the conquest fleet arrived. I am warned that only a threat of retaliatory violence from the conquest fleet has kept them from mounting attacks on this colonization fleet."

Felless felt far dizzier than she would have from weightlessness and sudden revival from cold sleep alone. She finally managed to free herself from the restraining straps and gently push off from the table. "Take me to a terminal at once, if you would be so kind. Have you an edited summary of the data thus far transmitted from the conquest fleet?"

"We have," Reffet said. "I hope you will find it adequate, Senior Researcher. It was prepared by fleet officers who are not specialists in your area of expertise. We have, of course, provided links to the fuller documentation sent up from Tosev 3."

"If you will come with me, superior female ..." the physician said. She swung rapidly from one handhold to another. Felless followed.

She had to strap herself into the chair in front of the terminal to keep the ventilating current from blowing her off it. Getting back to work felt good. She wished she could have waited till reaching the surface of Tosev 3 for reawakening; that would have been as planned back on Home, and plans were made to be followed. But she would do the best she could here.

And, as she called up the summary, a curious blend of anticipation and dread coursed through her. Wild Tosevites ... What would dealing with wild Tosevites be like? She'd expected the locals to be well on their way toward assimilation into the Empire by now. Even then, they would have been different from the Hallessi and the Rabotevs, who but for their looks were as much subjects of the Emperor (even thinking of her sovereign made Felless cast down her eyes) as were the males and females of the Race.

A male in body paint like Reffet's appeared on the screen in front of her. "Welcome to Tosev 3," he said in tones anything but welcoming. "This is a world of paradox. If you were expecting anything here to be as it was back on Home, you will be disappointed. You may very well be dead. The only thing you may safely expect on Tosev 3 is the unexpected. I daresay you who listen to this will not believe me. Were I new-come from Home, I would not believe such words, either. Before rejecting them out of claw, examine the evidence."

A slowly spinning globe of Tosev 3 appeared on the screen.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...