- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

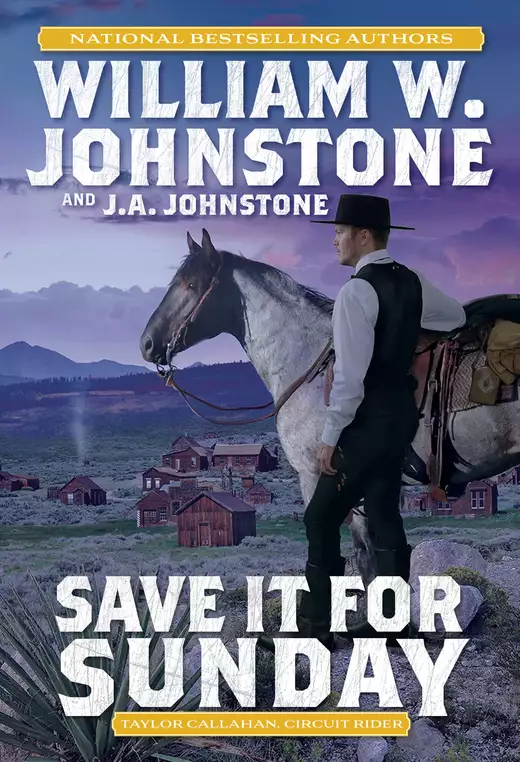

National Bestselling authors William W. Johnstone and J.A. Johnstone bring us the latest action-packed Western in the Circuit Rider series, the first Johnstone books to acknowledge a higher power and bring a subtle element of faith to justice in the Wild West.

JOHNSTONE COUNTRY.

GET YOURSELF TO A SUNDAY MEETING.

From Confederate marauder to rebel gunfighter to repentant preacherman, circuit rider Taylor Callahan’s road to perdition has been a hellish ride. Sinners beware.

After riding with Missouri bushwhackers, Taylor Callahan vowed to never take another life. He’s making good on it in Peaceful Valley. By day, swamping a saloon. By night, preaching the Good Book. But this little settlement is about to become anything but peaceable. When the marshal takes a bullet in a sheepman-cattleman skirmish he pins a badge on Taylor leaving the circuit rider open to whole new world of hell . . .

A railroad engineer building a line from Laramie to Denver is cutting across Arapaho land starting a war on Peace Treaty Peak. If that’s not enough to set the county on fire, Taylor’s trigger-happy past comes calling. The revenge-seeking Harris boys are hot on his tail. With the marshal down, Peaceful Valley is ripe for the taking—and blasting Taylor to kingdom come is part of the deal. If keeping the peace means breaking Taylor’s vow so be it. He’s looking forward to strapping on his Colt .45 again. That’s the gospel truth.

Live Free. Read Hard.

www.williamjohnstone.net

Release date: March 28, 2023

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Save It for Sunday

William W. Johnstone

And it came to pass . . .

It was a stagecoach, moving as though the hounds of Hell were trying to jump into the rear boot. It wasn’t a Concord, but one of those Abbott & Downing mud wagons—though the trail wasn’t even damp. Boxy-looking, not as big as a Concord and bouncing like it was out of control as the driver serenaded the six mules pulling the coach with every cuss word in his vocabulary. The leather curtains were rolled up. No guard to be seen.

Perhaps he had jumped off or quit.

The horse and rider nearby didn’t get a good look at any passengers inside.

It passed Taylor Callahan, riding the slow-footed white gelding he’d named Job, as if horse and man were standing still like wind-blown boulders sprinkled across the rolling plains.

Nary a salutation came from the driver, who spit out a stream of tobacco juice that shot past Callahan’s beard stubble like a minié ball.

And it came to pass . . .

Taylor Callahan ran those words through his mind again, nodded, and pulled down the kerchief as the dust kicked up by the mud wagon settled on the grass and rocks on the southeastern side of the trail. Yes, he could use that. It would work fine. It being the stagecoach. Pass being the verb and . . .

The jangling of traces and more ribald language caused Callahan to turn around. Could that be?

He eased Job farther off the trail, turned the gelding around to see another approaching mud wagon, also with a foul-mouthed driver and no guard. Remembering one of his pappies had always said, “Time brings wisdom to most critters,” Callahan had time and wisdom to pull up his bandanna and cover his mouth and nose again.

Once again, the driver paid no attention and made no gesture, friendly or otherwise, to the tall man in black on a white horse. But Callahan got a good look inside the coach. A handsome woman in a fine green dress, her hair in a bun, was holding what might have been a Bible. And she might have smiled at him, or perhaps Job. She even offered a friendly, fleeting wave as the coach rolled past.

Callahan let the dust settle again before he lowered the bandanna and nudged Job back onto the road. He looked behind him a good long while before he felt satisfied no more speeding mud wagons were stampeding north. And he forgot about any puns or wit he would display at his next preaching, as he just let the gelding carry him leisurely north.

However, he did keep looking over his shoulder while plodding across a country that looked like waves on the ocean. He wanted to make sure no other coaches came up behind him. The last thing he wanted was to be greeted by the Major General in the Heavens at Saint Peter’s Gate and be told he had been killed after being run over by an Abbott & Downing Company mud wagon.

The sun had started to sink behind the mountains far off to the west. Coming out of Denver, Colorado, Callahan had thought most of the Rocky Mountains would be like the Front Range just west of Denver. Mountains reaching to the skies, often their tops disappearing behind clouds. But in what Callahan figured had to be Wyoming Territory, the mountains appeared to be a good ride southwest or northwest.

Oh, they weren’t flat plains like he had seen in Kansas, or just last year way down in southern Texas. The way the wind blew the tall grass, Callahan almost thought he was in an ocean. Which reminded him: I still ain’t let my eyes feast on an ocean.

That had been his plan when he was drifting south in Texas. To see the great seas, where the whale had swallowed Jonah, though some blowhard Texan had told him he wouldn’t see an ocean, just the Gulf of Mexico, or maybe even nothing more than the Corpus Christi Bay. He had hardly seen anything wet except one of the most vicious flash floods he had ever witnessed. And coming from a childhood in western Missouri, Taylor Callahan had seen many a flood. The Mighty Missouri was no little crick when she flooded. One of the first funerals the Reverend Taylor Callahan had ever preached was for a ten-year-old boy who got caught when the Sni-A-Bar Creek got to raging.

That reminded him of the four Harris boys. If they had not been lynched or shot down like the dogs they were—May the Major General in the Heavens forgive me for thinking in such an unforgiving kind of way—they could be after him yet.

He reined in Job and looked down the trail. The dust from the two stages had long settled. No travelers could be seen as far as he could see. And he could see a right far piece in that country. Hills were all around him, popping up here and there, rocks strewn about, and he could even find a tree, usually along the creek beds, even though he’d not seen much in the way of water in those creek beds.

Strange country. Pretty, but different. It looked as though the old Major General in the Heavens had been trying to see what He or She ought to make Wyoming Territory look like. Maybe the General had decided those mountains off to the west were too much like Colorado and the Great Plains had already been perfected when Kansas got created. How about some of these red rocks and boulders and dust to blow? That ain’t half bad, but, well . . . Callahan understood. He had seen parts like that when he had left Texas and ridden up through New Mexico Territory, mostly following the Pecos River.

The hills he was riding through weren’t consistent, either. Some of them were rolling like the waves, but here and there he found buttes, mostly barren, some with boulders that appeared to have been dropped out of the sky.

Meteorites? Maybe all those shooting stars he had seen, sometimes making wishes on, though rarely, if ever, seeing one of those wishes come true. Those stars had to land somewhere. But the rocks like the two Job was riding between did not look like the moon did when she was close and shining bright, nor had that little piece of hard rock he had paid a three-cent nickel to see at that dog-and-pony show in Trinidad, Colorado, a few months back. The professor swore it was a part of a meteorite that had come past Mars and the moon and landed in Utah back in ’69. But he might not have been the most honest person since his assistant was peddling bottles of Doctor Jasper’s Patented Soothing Syrup—guaranteed to cure infant colic, consumption, whooping cough, female complaints, malaise, and warts.

Just before darkness fell, Callahan found a muddy bit of water where a little creek made a bend around another boulder, and he stopped there. Loosening the cinch but leaving the saddle on the gelding, he let Job graze and drink. Pulling another bandanna out of the saddlebag, he used it to strain water into a coffeepot. Just enough for two cups of coffee.

He built a fire, stretched his legs, pushed back his hat as the water began to boil, and turned his thoughts to how far he had ridden since Denver.

The carpenter Callahan had been working for in Fort Collins had said it was about a hundred miles from Denver to Cheyenne, but keeping track of miles traveled came hard for this circuit-riding preacher. The carpenter had hated to let Callahan go, and since they were building a church, he had kept delaying his departure, even though the church already had hired a minister who was coming in from North Platte, Nebraska, if he didn’t get scalped by Sioux and Cheyenne. The congregation was decidedly Episcopal, and Callahan had known many a fine Episcopalian, and even had enjoyed a pilsner with one of that cloth—before the War Between the States, anyway.

He had moved on to Poudreville, preached a few days at the livery, and then went through Virginia Dale, preached in a saloon, before lighting out again.

Callahan knew he was in Wyoming by now. The beer jerker at Virginia Dale had said the territory wasn’t more than a hop and a skip away. While Job had never been inclined to hop or skip, they had gotten a good start not long after breakfast.

Callahan remembered the conversation.

“Just follow the trail,” the beer jerker said, “and make good time. Indians be on the prod.”

“Most of that’s way up Montana way,” the faro dealer corrected.

“They’s enough injuns between Montana and New Mexico to give us fits.”

As he rested and drank the coffee he’d made, Callahan continued thinking about that conversation.

“Best to travel at night,” the beer jerker told him. “Injuns won’t attack at night.”

“Who told you that?” the faro dealer barked.

“An old-timer at Fort Lupton.”

“That ol’ coot? His brain left him before the Pikes Peak crowd showed up in Colorado.”

“I read that in the Denver Twice-Weekly Reporter, too.”

“You can’t read.”

“Plantin’ moon,” the beer jerker said.

“Raidin’ moon, you moron,” the faro dealer countered.

Callahan shook his head. They’d still been going at it when he had pulled on his hat and left the saloon for the stable.

He stood, massaged his thighs and buttocks, emptied bladder and bowels, washed his hands in the muddy stream, and looked at the moon. Since it was full, he figured it would be light enough to follow the road, even if the road was really nothing more than tracks of wagons—like those fool mud wagons he’d encountered—made by flattening the grass.

Callahan was used to traveling at night. Back in Missouri, he’d traveled a lot without even a moon to guide his way. But that’s what a lot of Missouri bushwhackers needed to do during the late War Between the States. Carbine Logan’s boys made a habit of not being seen. That was a long time ago though, back when Taylor Callahan was younger and impetuous, and a tad bitter and angry.

He was a changed man now.

He was also broke.

The money he had made working for the carpenter in Fort Collins did not amount to much, and while the livery in Poudreville had paid him in coffee and hard tack, the coins collected in the black hat Callahan passed around barely covered the feed bill he had been charged for Job’s appetite. He had done a wee bit better in Virginia Dale till that old codger with a wooden leg came in with a story about an ailing wife, all four kids with the croup, and not enough money to hire the barber across the way who sometimes doctored folks up.

“Here’s what I can give you, old-timer,” Callahan had said, and dumped his change into the man’s calloused hands. “As long as you promise me you ain’t buying Doctor Jasper’s Patented Soothing Syrup.”

“Cures warts,” the faro dealer had said.

“No, it don’t,” the beer jerker had argued. “But it works wonders on the grippe.”

Callahan wanted to get to Cheyenne so he could maybe get enough tithes to spend at least one night in a hotel with hot bath water and decent linens. Maybe even a shave since he had traded in his straight razor for a bit of ground coffee in Poudreville.

The faro dealer at Virginia Dale had told him not to go to Cheyenne, but make way to Laramie. It was closer and had a lot of sinners.

The beer jerker had said, “No, the real action is to be had farther west, at Fort Steele on the North Platte because nobody sins worser than soldiers that far from the civilized world.”

That’s why Callahan had picked Cheyenne.

He kicked out the fire, doused the smoke with the remnants of his coffee, and got to work on Job, tying the coffeepot to the bedroll, tightening the cinch, saying a short prayer, and eating the last bit of beef jerky he had been saving. Looking up, he checked the moon, waited for it to rise just a bit higher, and then opened the saddlebags. He pulled out the .45-caliber long-barreled Colt revolver, and checked the loads. He thought about sticking it inside the deep pocket of his black Prince Albert coat, but decided against it.

Indians might have a different color skin than Taylor Callahan, and likely practiced a different religion, but if the faro dealer had been right, Callahan would rely on his faith, and the Major General in the Heavens, to protect him. His will, or Her will, be done.

He returned the Colt to its place, fastened the buckle, moved around Job, keeping his hand on the gelding’s hide so not to get kicked, and reached the other saddlebag. Opening it, he touched the Bible, said a brief prayer, and found two corn dodgers. He thought about eating one but figured the salt would just make him thirsty, and took them to Job, letting the horse eat the stale balls of bread.

Callahan led the horse back to the trail, which would be easy to follow on a cloudless night, tightened the cinch again, and eased into the saddle.

Job snorted.

“You’ll get a fine stall and a good rubdown in Cheyenne,” Callahan told him.

That was a bit of a prayer, he realized. But maybe the Major General in the Heavens was listening and feeling charitable.

Callahan laughed when Job bucked twice, an informal protest, but the preacher was a better horseman than many people—at least those who had never known him as one of Carbine Logan’s Irregulars—realized.

“You done?” he said, then kicked the gelding into a slow walk.

“That’s what I figured.” Callahan shook his head and clucked his tongue. “Two jumps and you’re played out. Come on, boy, just follow the trail.”

He’d done some figuring while he’d rested and the way he figured, those stagecoaches that had almost run him and his horse over that afternoon would not be traveling at night. Maybe he could be out of their way by the time dawn broke if, by chance, they started making a return trip to whatever burg they had come from.

He grinned, hearing his late ma telling him with some amazement, “You got some brains beneath that hard skull of yourn that I never knowed you had, boy. How come you don’t always act like you know somethin’?”

An hour later, he realized he had erred. As the stagecoach barreled toward him, he could hear his late ma’s voice again.

“Boy, you ain’t got the sense the Lord give a corncob.”

Riding horseback at night had its risks. Taylor Callahan understood that. The odds—he remembered a thing or two about such things from his wilder years when he saw nothing sinful about wagering on anything—likely favored a stagecoach over a man on horse. Even with a shining moon. A stagecoach, after all, had headlamps. A stagecoach would not likely be startled by a rattlesnake or a pronghorn. And most stagecoach drivers did not whip six mules into running at a hard gallop over not much of a road up and down a steep hill.

Thank the Major General in the Heavens.

Callahan—and Job—heard the rattling of the coach, the cannonade of hoofbeats, the snapping of a whip, and the reprehensible language of the driver, giving the circuit rider time to turn the white gelding off what Wyoming called a road.

Neither horse nor rider expected the lead and trailing mules to leap into view on the crest of the hill. The stagecoach went airborne. The mules and driver—again, no one rode as a guard—spotted Job, beaming brighter than he actually was because of the big moon. Mules might not be spooked by a rattlesnake or an antelope while galloping hard, but seeing a ghostly figure in black atop a bright white steed led to a totally different reaction.

The mules turned left, away from Job and Callahan on the right. The driver shouted out something lost in the chaos that followed, and Taylor Callahan knew he would never know exactly what happened till that glorious day—many years from now, he prayed—when he stood at the Pearly Gates and heard the story from the Major General in the Heavens.

The mules and driver were not the only ones spooked. Job started bucking.

The top of the stirrups caught Callahan’s boots when the gelding kicked out his back legs, right before the seat of the saddle caught the Missourian’s crotch when the horse’s legs touched ground. Those moves repeated themselves for four or five or fifty more jumps. Well, Callahan would concede later, it probably did not get as high as fifty, but that didn’t mean he couldn’t use it in a sermon at a camp meeting now and then. In any event, once his right foot lost its hold in the stirrup, and Job’s twisting, turning, bending head jerked one rein from Callahan’s grip, he knew he was not long for the ride. He kicked his left foot free, let go of the other rein, and propelled himself off his mount on Job’s next high kick.

He landed on his left foot, bounced up, twisted around, and fell on his back. His legs landed next while the air rushed out of his lungs, and he felt a sharp pain in the back of his head. Since he had no idea where Job might be bouncing around, Callahan did not wait to wiggle his fingers and toes or turn his head one way or the other. The last thing he wanted was for eight hundred pounds of glue bait to stomp the life out of him.

Rolling over sage and rocks and cheap grass, he realized he had not broken his back or neck. Once he stopped, he shoved his hands flat on the ground and pushed himself upright.

There he stood, breathing in dust. As his lungs worked extra hard, he wet his lips with his tongue, and turned to find Job. The horse had bucked itself out pretty quickly. That came as no shock, but the gelding remained out of sorts, ears flat against its head, staring off to the southwest, and pawing the earth.

“Easy—” Callahan said, surprised that his jaw was not broken.

But he never got to finish saying, “boy,” for behind him came a deafening crash, followed by hideous screams of man and beast. The next words that escaped from Callahan’s mouth would not please the Major General in the Heavens, but the battered preacher could remember to ask for exception and forgiveness later.

He turned around as dust rose like fog glowing white and tan and ominous in the bath of moonlight and started up the incline toward the path that pretended to be a road. Then, he stopped suddenly, turned around, found his hat, and took one more glance at Job. Satisfied the gelding wasn’t going anywhere unless someone dangled a carrot, Callahan pounded some shape back into his Boss of the Plains, rid it of dead grass and some of the dirt, and reached the trail.

More dust rose in separate locations. The thickest cloud was southwest, maybe forty or fifty yards—what was left of the stagecoach and driver. The other dust came from the mules, all six of them, still in their traces and making good time for Virginia Dale, Poudreville, Fort Collins, Denver, Hades, or wherever those animals felt like stopping.

Callahan stopped, bit back another unkind word, and turned around. Job stared at him as he approached, but seemed to have calmed down a mite. The preacher hummed softly. The saddle was leaning far to the right, and the canteen was missing from the horn. He walked to the horse anyway, maybe just to let the animal know he was well thought of, which might not be entirely true. Reaching the horse, he rubbed the white neck, and gently pulled the saddle back into place. He looked around for the canteen, but didn’t see it, and didn’t want to spend the rest of the night looking for it. Most likely, he would find it or trip over it this evening or tomorrow morning. At the moment, someone else needed his attention.

“Easy, boy. Just eat some Wyoming grass and get some rest. I’ll be back directly.” Callahan turned, shook his head, sighed, then thought about swearing a bit more, but did not go through with it.

He returned to the trail and moved in the direction of the crumpled heap that once was a mud wagon. He heard the moaning, but ignored it for the time being. Leaping up onto the kindling that passed for a stagecoach, he peered through the opening. Nope. No one was inside. A good thing. He held that thought for a moment when clarity, slow to come, returned. Like the moaning driver, a passenger or passengers could have been thrown clear of the mud wagon.

Callahan backed up and studied the rolling waves of grass, hills, bounders, and one antelope that had come out to see what was going on. No humans appeared or at least none the circuit rider could see, which didn’t mean there weren’t any.

The driver, loosely defined, started moaning louder, so Callahan walked toward the groans. The man lay on his back, boots crossed at the ankles as though he were being laid out for the undertaker, arms stretched out over his bearded head. His nose was leaking blood, which stained his white mustache, and his lips were busted, but the man still breathed, and his breath reeked of bad whiskey.

His eyelids moved, gray eyes focused, and he spit out blood and saliva before asking timidly, “Are you God?”

“No.” Callahan knelt.

The man gasped. “The . . . devil?”

“Not the devil you should be seeing.” Callahan ran his right hand over the man’s ribs, noticing the man’s eyes were wild with fear, but he didn’t seem to feel any agony where Callahan applied pressure.

“I could use some whiskey,” the driver said.

“You ain’t the only one, Brother.” Callahan looked at the man’s hands and ordered, “Wiggle the fingers on your left hand.” He waited. And frowned. “Are you wiggling?”

“Yeah.”

Callahan sighed, and turned to look at the man’s battered face and broken neck. Something else grabbed his attention, and he fought back that urge to curse again. “Your left hand.”

The man looked confused, till the fingers on the left hand began to move. Then he just looked stupid.

“Turn your feet, left to right, or right to left. It don’t really matter.”

That he did without any stupidity.

Callahan let out a sigh. The Major General in the Heavens did look after idiots. He stared down at the driver. “Where all do you hurt?” he asked, knowing the answer.

“All over!”

“Can you stand?”

“I could use some whiskey.”

“Do you think you could stand?”

“I said I could use—”

“I heard you the first time, but your breath tells me you’ve had enough whiskey. Now, can you sit up at least?”

The man whimpered. But he did bring his arms to his side, and used his forearms to push himself up. Callahan reached around and grabbed the driver’s shoulders and eased him till he was sitting in the dirt.

Seeing what was left of the Abbott & Downing wagon, he cursed. “What happened to my mules?” he cried out. “Tell me they ain’t dead.”

“They were lighting a shuck south last I saw,” Callahan answered.

“You shouldn’t have startled my team so,” the man complained. “It’s your fault. You’ll have to answer to the Poudreville Stagecoach Company.”

“Mister,” Callahan said, “I wasn’t the one drunker than a bluebelly on payday. Nor the one whipping a team like a maniac uphill and downhill on a road seldom traveled. All like there’s no tomorrow.”

“There ain’t gonna be no tomorrow if I don’t get to Poudreville before the Peaceful Valley stagecoach does.”

That statement brought back memories from the afternoon. The second mud wagon. The one with the female passenger who had smiled—or at least Callahan had fancied a smile—that was being whipped just as wildly. He looked toward the road and up the hill. He also listened, but just heard the driver’s groans, moans, and then, a stinking, rippling, long whiskey fart.

Callahan glanced at the moon and asked the Major General in the Heavens what he had done to deserve such punishment, but stopped quickly, whispered an apology, and looked down at the battered old driver. “My name’s Callahan. Taylor Callahan. Circuit-riding preacher bound for Cheyenne.”

“Preacher?”

“That’s what I said.”

“In Wyoming?”

“If this indeed happens to be Wyoming.”

The driver blinked and stared, which he followed with a stare and a blink. Then he remembered his manners. “My name’s Absalom.”

Callahan laughed so hard his ribs almost broke. Tears filled his eyes. Drunk as that driver was, as beaten up as he had to be after that wreck, the man had a wicked wit underneath that raw, rank exterior.

“What’s so dad-blasted funny?” the driver wailed.

“Absalom!” Callahan shook his head.

“That’s my name.”

Callahan laughed again and shook his head. “Your name can’t be Absalom?”

“The devil it can’t!” the man barked with genuine sincerity and, if Callahan were not mistaken, a good deal of anger. “Why can’t it be?”

Perhaps this drunken fool was a thespian to match the talents of Edwin Booth. The preacher might have felt sorry for the old cad, till he heard Job walking toward him and saw the ruins of the mud wagon and remembered trying to ride out a bucking show by the usually lazy gelding. “Because you ain’t hanging between two boughs of a big old oak tree, ‘between the heaven and the earth,’ though your mules sure had the right idea.”

“Huh?”

“Second Samuel, Chapter Eighteen. But don’t ask me the verse. Not till morning, maybe afternoon, when I ain’t so flustered.”

“I don’t feel so good, Preacher,” the man said, and sank back to the ground.

Kneeling quickly, Callahan placed the back of his hand on the man’s forehead. The eyes fluttered, but did not open.

“Where do you hurt?” Callahan asked.

“Everything’s just spinnin’,” the man whispered. “Spinnin’ like a top. Feel sicker than a dog.”

Could be the whiskey, or a bad combination of whiskey and wreck.

“Don’t let me die, Preacher.” The man’s voice barely. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...