- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

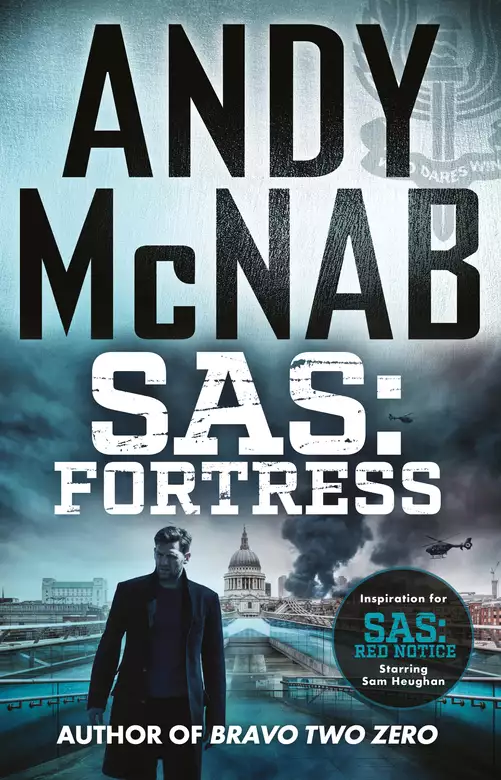

CONTINUE THE ACTION FROM MAJOR MOTION PICTURE SAS: RED NOTICE WITH BOOK 2 OF THE THRILLING SERIES FROM BEST-SELLING AUTHOR ANDY MCNAB

Tom Buckingham has blood on his hands.

Neck deep in trouble for taking down a renegade Afghan soldier, he’s sent back home—angry, betrayed and out of work.

But with riots and rebellion spreading like wild fire on the streets of Britain, Tom’s unique skills are soon noticed by a charismatic billionaire with a questionable agenda.

Buckingham finds himself thrown back into the covert world of intelligence where a play for power is underway. He’ll have to decide where his loyalties lie if he’s to intervene in a series of events that will threaten the whole nation.

Time is running out and lives are at stake; is there anyone Tom Buckingham can trust?

_____________________________________________________________

What people are saying about SAS: Fortress:

????? "Plenty of twists and turns in a well constructed theme which takes the reader into the minds of the characters."

????? "Timely, and frighteningly believable."

????? "Enthralling! Gripping from start to end, a real page-turner."

Release date: July 6, 2021

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 464

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

SAS: Fortress

Andy McNab

Walthamstow, East London

28 June

The target’s hands hovered each side of his head, shaking so much that they looked like they were about to fall off. Callum’s forefinger curled round the trigger of his Heckler & Koch MP5SF, his right eye studying the target’s wide-eyed grimace down the night sight. The man, IC6 – Middle Eastern, early thirties, six one, well built – stood framed in the Transit’s open passenger door, lit by the glare of the halogens from one of their 5 Series ARVs.

‘Name?’

All that came back was the high-pitched whinnying sound of the man, who was either a terrified van passenger or a wannabe suicide bomber.

‘Name, now!’

‘Still no DSO,’ shouted Vic from the car, his headset mic flipped down, mobile pressed to his ear. But it didn’t matter at that stage. Even if they hadn’t lost radio contact, SCO19’s designated senior officer back in the control room at Scotland Yard couldn’t see what they were seeing. Soon they would have cameras on helmets, but not yet. Right now they were on their own, the choice theirs: to kill or not to kill. Callum was the lead; it was his call, his neck if they fucked up.

‘No wheelman.’

Cook, who’d taken off after the driver had done a runner, had given up the chase, his words pushed out between gasps of breath.

Even though it was past two a.m., the hottest day of the year was showing no sign of cooling. A short, sharp shock of rain had merely covered the street with a sticky slick of gloss that was now steaming the place up. Vic was dripping with it and even Callum who, a few lives back, had seen service in hell-hot Sierra Leone and, even further back, had had a few sweltering holidays with his gran in Jamaica, was feeling it.

His brain scrolled through standard procedure.

Target should drop like liquid. Aim for the head to avoid triggering explosive devices attached to chest or waist: tick. Confrontation to be made in secluded location to avoid risk to personnel or public: tick. Prepare to fire multiple shots at the brain stem to minimize the risk of detonation. Brain stem? Who wrote this shit? This wasn’t keyhole surgery.

The man’s mouth moved. ‘Suleiman.’

At last, a name.

‘Suleiman what?’

‘Suleiman, sir?’

You had to laugh.

‘The rest of your name.’

‘Nazul. Suleiman Nazul.’

Callum could hear Vic’s fingers dancing over the laptop, then an agonizing pause.

‘Negative on that. No form coming up.’

The sweat pouring down Suleiman’s face was being blotted up by the T-shirt under his padded gilet. Who wears a fucking padded gilet on a night like this? What’s in it? Duck down or Semtex? One of his wobbling hands strayed close to his streaming head.

‘Hands back up! Up! ’

There had been no warning, no build-up, no plan. Fresh intelligence from a trusted source, the control room had said. Scramble. The Transit, white, 02 plate; contents on board reported to include syringes, latex gloves, clamps, drills, aerosols and a generous quantity of hydrogen peroxide. Someone fitting out a hair-dressing salon? Right. And a .380 starter pistol converted to fire live rounds. The passenger, believed to be a British jihadi recently returned from Syria, nom de guerre: Abu Salayman de Britaini; given name unknown. Was this him?

Callum nodded at Wren beside him. Wren moved towards the rear of the van, tried the door, opened it a bit, then wider, then both doors.

‘Negative.’

Wrong van?

Wrong man?

Callum adjusted his stance and lifted his head an inch above the sight so he was looking at the man eye to eye. He was fresh from his annual requalifying at Gravesend, stuffed to the gills with the latest guidance, essential if he was to keep his firearms ticket.

‘Okay, Suleiman, here’s what’s going to happen. When I say so, you’re going to keep your hands as high as you can while you get down on your knees, then, keeping your arms stretched, lower them to the ground and lie face down. You got that?’

He nodded eagerly. Maybe he thought his life wasn’t over after all.

‘Okay: one, two, three . . .’

On three, two things happened. Callum heard the crack of a round passing him at supersonic speed, followed by the thump of a weapon’s report. Suleiman spun round as if someone had cut his strings and dropped – like liquid – to the ground in a cloud of pink mist.

‘– the fuck?’

Callum wheeled round, leaped behind the car for cover and scanned the building behind them. Less than half a second between the crack and the thump meant a firing point less than a hundred and fifty yards from the target. An oblong slab of flats, unlit, deserted, awaiting demolition.

In seconds, Vic was at Suleiman’s side with the emergency kit, rolled him over and cradled his head, the half that was still intact. He looked up at Callum.

Nothing to be done.

2

Camp Bastion, Helmand Province, Afghanistan

‘I’ve decided.’

Dave Whitehead peeled off his kit and let it drop onto his cot – M4, waistcoat stashed with extra rounds, Sig 9mm, Kevlar helmet, Gen 3 NVs, sat phone, sweat-sodden MTP, vest, socks and boots: it came off in layers until all that remained was the basic soldier in a pair of boxers featuring Stewie the homicidal baby from Family Guy.

‘Decided what?’

Tom Buckingham was only half listening as he steered his laptop round their quarters in search of the ever elusive Wi-Fi signal. The whole row of Portakabins had been plagued by glitches all week. He glanced at the time: 23.00. Six thirty in Hereford. Ten minutes to his Skype with Delphine. He needed to be ready, and alone.

‘Came to me in a flash while we were out there today.’

The screen burst into life. The BBC News Home page: Outrage at killing sparks nationwide riots. Nine dead, hundreds injured. Tom lowered the laptop onto the shelf under the window, checked the signal strength, clicked Skype onto standby and tried to absorb the news from home.

‘Hey, listen up.’

Something about Dave’s tone told him he’d better pay attention. He turned away from the screen.

‘I’m serious. When this ends, it’s time to get out.’

It was the start of their second sweltering month at Bastion, tasked with babysitting an Afghan National Army mission to lift a Taliban chief as he broke cover and crossed from the Tribal Areas into Helmand for a shura, a tribal meeting. They wanted him alive, so no taking him out with a drone. But the shura kept getting postponed. So they waited, rehearsed and waited some more. Today should have been The Day. But when they’d hit the safe-house the guy was supposed to be in, it was deserted.

Tom, already down to his vest, glanced in the mirror. Dave, behind, signalled to him to pay attention.

‘You know, bin it while I’m ahead.’

He had confided in him about leaving a few days ago, starting a new life, getting on the troops-to-teachers programme. Tom had thought it was a wind-up. He gestured at the laptop, his mind elsewhere. ‘Can this wait? I’m kind of on standby here.’

Dave, ignoring him, popped a can of Monster and poured it down his throat. ‘After all, I’m great with kids, aren’t I?’

Only last week, on an exercise with the ANA, Dave had covered himself in glory by pulling an eight-year-old boy out of the rubble that had been his home and delivering him into the arms of his frantic parents. When they’d gone back to see the family, Dave had taken a basketball he’d liberated from the same US Marines that now made up the vast majority of troops in Helmand, fixed up a makeshift hoop for the kid and shown him the ropes. Within minutes he was surrounded by ten more eager players.

‘Yeah, it’s a great idea. Now can you fuck off for a bit while I talk to Mademoiselle?’

Dave threw his head back, drained the dregs of his drink, tossed the can into the bin with deadly accuracy and lay back, wiping droplets of liquid from his blond stubble. Flung together by the SAS, they were planets apart. Tom, all blue chip and silver spoon, had seen pictures of Dave as a kid, a skinny, scruffy urchin with spindly legs, scabs on his elbows and big flappy ears. Removed from his drug-addicted mother at four, he had weathered every indignity the care system could heap on him, as he was bounced through a succession of homes and foster placements, his spirit undimmed, until the Army had thrown him a lifeline. There, he had blossomed, single-mindedly transforming himself into the fine fighting machine that now lay spread-eagled on the cot and scratching his ball-bag.

‘I mean, look at you, playing soldiers while Her Indoors waits in vain. When you gonna get your act together?’

Dave had a theory he loved to expound on about doing one thing at a time and had given Tom a hard time for saddling himself with a fiancée.

‘Tell you what,’ said Tom. ‘Just fuck off to the gym.’

‘I’ve decided. Don’t try to talk me out of it.’

‘There’s a new USAF one. They’ve got a whole rig of great kit in there, chest press, pec fly, gyroscopic dumb-bells. An hour of those and you’ll sleep like a baby. With a nice clear head when you wake up.’

‘My head is clear.’

‘Sure, sure, I know. Their AC runs off its own genny. You’ll look cool and be cool. Now split.’

‘You sound like an ad for deodorant.’

‘I’ll catch you up, okay?’

Dave reared up and was on his way out of the door.

‘Where’s your weapon?’

He patted his holster.

‘I’m going to the gym, man – not patrol. Hey . . .’

Tom paused, his fingers on the keyboard.

Dave grinned. ‘You’re a lucky bastard, you know that?’

The door swung shut and he was alone.

Tom glared at the laptop, not relishing the upcoming communication. Skype seemed to be the worst of both worlds. He used to like to write letters. At prep school, every Sunday after chapel, they’d been made to. He’d listed the week’s academic achievements – that bit didn’t take long – then his various triumphs on the field. Dear Mum, I got two trys in rugby and got sent to the Head for fiyting Robbo only it was just play. Nothing broken so you don’t need to tell Dad. The ginger cake is all gone. Please send a bigger one this time if poss. Love from Tom. He’d carried on after he’d enlisted, deaf to the hoots of derision from his mates. But it was easier than phoning – no grief coming back at him.

He clicked on BBC News again, scrolled through pictures of a street of shops in flames, a mounted policeman, face bloodied, helmet gone. Even the ANA had heard about it, the interpreter raising an eyebrow at him at breakfast, as if to say, Welcome to our world.

Delphine would have something to say about all this.

He stared at his reflection in the window. A hundred metres away, he saw a small glow of light. It flickered once, then twice more – a lighter, perhaps. Maybe a cigarette would help. After a long abstinence he’d lapsed, then promised Delphine he’d stop. That had lasted about three days. A pair of Ospreys thundered overhead, landing lights off to deter enemy fire, yet plain to see from all the light thrown up by the base. It was huge: as big as Reading, its air traffic busier than Gatwick’s. Brits, Americans, Danes and the fledgling Afghan National Army were all here. The ANA were in charge now, the end in sight for the Coalition, though it didn’t feel much like it.

The aircon stuttered to a stop and, in a matter of moments, the room heated up to an uncomfortable level. Great. Fucking perfect.

The laptop came to life. Delphine was there.

‘Hey, babe.’ Seeing her lifted his spirits instantly.

‘Bonsoir, mon chéri.’

She blew him a kiss. He blew one back. Why did this make him think of prison visits?

‘You’ve caught the sun again.’

‘Hard not to – it’s up to forty-five.’

Neither of them had got the hang of this.

‘How’s your day going?’

‘Oh, you know. Same old.’

Her colloquial English was coming on. But it was clear something was wrong. She looked tired and drawn and, although she’d probably touched her face up for the chat, he could see her eyes were red from crying.

‘Are you okay?’

‘Tom, it’s not good here. I don’t like it, what’s happening – all this trouble, I don’t feel safe.’

‘It’s just people letting off steam, taking advantage.’

Instantly he felt the shallow gloss of his words. ‘There’ll be nothing like that where you are, trust me.’

Her shoulders rose and she let out a dismissive sigh. ‘You say that, but people right here in the bar, they’re saying terrible things about what should happen to the protesters. It’s all so ugly.’

Delphine was right. It was ugly, but the chances of her coming to any harm at the Green Dragon in Hereford were less than zero. The lads back at the Lines would see to that. He’d told a couple of them to look out for her.

‘Trust me, it’ll all die down. Stuff like this happens all over – this could be Paris or Lyon or Marseille.’ Now he could hear the impatience in his tone. Civil strife, ethnic tensions, tribal conflicts, you name it, he’d seen it – in Benghazi, Beirut, Kinshasa, Kirkuk. In Western Europe we don’t know we’re born, he felt like saying, but that was the last thing she needed to hear.

‘Why do they keep extending you? Tell them you want to come home.’

Now it was hitting them what different worlds they occupied, what it meant to be an army fiancée – let alone a wife, if they ever got that far. Had he misled her? She knew some of the wives back in Hereford and must have heard the gripes. This was his first long job away since they had got together. It had all happened so fast: just forty-eight hours’ notice. This was how it was going to be: she had to realize that.

‘It doesn’t work like that, babe. They give the orders. I do what I’m told.’

Her face disappeared from the screen for a moment. When it reappeared she was dabbing her eyes with a tissue. ‘I keep thinking how different it could have been.’

He didn’t need to ask what she meant. First there had been the Eurostar incident. She had been so brave, standing up to the hijackers, helping him defeat them. His respect for her then was total. But it had taken its toll on her – with flashbacks, nightmares and an under-standable fear of tunnels. And then losing the baby, their baby. Their different responses to grief had opened a void between them. He knew all about loss. He could have written a book about it. But none of it was working for her.

‘Look, we’ve got the whole of our lives ahead of us. We can try again.’

It sounded weak and clichéd, but what else could he say? How could he comfort her, reassure her from a desert fortress more than three thousand miles away? The pregnancy had been a complete accident, parent-hood something he hadn’t even considered. But he’d supported her all the way, even fancied himself as potential good dad material – when he was around. But it wasn’t to be.

He had dealt with more than his fair share of death: seen mates killed, shredded, vaporized, smashed to pieces so small there was nothing to bury. But watching your own child die as it was being born, and its distraught mother turn her face away from you in grief? There was no training for that.

‘Look . . .’ he began. The screen flickered, but he soldiered on. ‘Why don’t you go home for a bit, get away from all this? Find some . . .’ He’d been going to say ‘perspective’ but that would have sounded as if he thought she was being irrational. ‘Get some decent rest. Clean French air. Your mum’s cooking. Cassoulet and tarte Tatin. Mmm, fantastique.’

This time she couldn’t help smiling. He had only stayed with them once and had overeaten spectacularly. Her father’s expression had implied concern that a man with so little self-control should be allowed anywhere near live ammunition.

‘The pub can arrange cover, I’m sure, and—’

‘They have. Moira has found someone.’

‘So it’s already sorted?’ He tried to keep the dismay out of his voice. ‘Good! That’s – good. You need to get away.’

Then the line was gone. Her sad, perfect face was sliced and diced into pixels, then discrete blocks of colour that froze and slid away, like a surreal, digitized version of Jenga.

‘Fuck it.’

He grabbed his pistol and followed Dave out into the baking night.

3

Perimeter of Camp Bastion

They flattened themselves against the dirt, head to toe like a line of ants, moving forward in the darkness, out of the mud-walled village towards the poppy field. There were twelve and the Leader, levering themselves forward on their elbows, four of them not yet out of their teens. Isamuddin’s face was still completely smooth, without even the beginnings of a moustache. All were full of hope for the better life awaiting them.

Every day for two months they had trained under cover, behind walls and under improvised awnings, building their strength, assembling the devices, memorizing the layout of the infidel base, the size of a city, from a map scratched onto the wall of the room that had been their living quarters. As he pulled himself forward, Isamuddin risked a glance behind him at his brother. But Aynaddin wasn’t looking. His eyes were tight shut, tiny points of light betraying the presence of his tears. Only his lips moved in silent recitation. Isa tried to send him a thought message: Do not worry, little brother. You and I will soon be in glory. But all Ayna heard was the verses he repeated over and over to jam all his other thoughts – of doubt and paralysing fear.

Isa looked up into the starless night, a vast cavern that guarded their ultimate destination. His heart thumped at the thought of what awaited them after they had done their duty. The poppy was their last cover. Once through that they would be out in the open, with only half a kilometre of dirt before the perimeter. The orange glow of the floodlights was already visible beyond the foliage. He heard a sharp hiss a few feet ahead from the Leader, invisible in the darkness, who seemed to have eyes that glowed in the dark. Isa dropped his head so his nose scraped the dirt as he had been told, and kept on moving towards the poppy, where they would switch to a crouching run, guarded by the tall stalks, quickening their pace towards the target.

The base had been there barely four years. It had taken shape with astounding speed, an instant fortress city of concrete, metal and wire on a previously barren plain. So many thousands lived behind its walls that the sewage run-off had given life to the desert, and fields of poppy had sprung up. Before, the invaders had destroyed the crop, eradicating the extra source of income. But all that had done was antagonize the population.

They look strong with all their machines and missiles but, as you will see, they are weak, the Leader had explained. They have grown too sure of themselves, and because of that they are lazy. And on their useless diet of junk they have become fat and slow, while we have speed and patience, which is why we will prevail. The Leader had many such explanations for why victory was assured. The last reason, he had said, was They do not give their lives as you have chosen to. For this reason we will prevail.

Isa didn’t remember choosing. He remembered the Leader appearing one night on a grey mare and telling his father that the boys of the village had been chosen to serve the Almighty, and that he should celebrate his good fortune. When his father had stood there, dumb-struck, the Leader had swung the AK47 into his face and knocked him to the ground. Before he could rise, the Leader had pushed the barrel of the gun into his mouth. Only Mother’s dramatic display of gratitude had stopped him pulling the trigger.

Inches in front of his face Isa could just make out the heels of Khanay, his cousin, the hard calloused shells of skin built up over years of going barefoot, the loose legs of the oversized Afghan National Army uniform flapping around his ankles. And on his back, the dark mound of his pack stuffed with the devices they had prepared. Khanay had got the message. This is the greatest day of our lives! he had exclaimed, his eyes wild. Until this night we have been peasants of no value. Tomorrow we shall be princes, honoured by our family forever.

The stolen uniforms were strange. Isa had never worn new clothes before. The stiff fabric between his legs chafed. They had forgone the boots, which had felt like metal cases round their feet, once they knew that the ANA themselves often went without, preferring sandals or bare feet. Four hours earlier they had stood in front of a video camera while the Leader recited his speech to the world in English. I give this message to the infidel crusaders . . . We will burn you and your weapons . . .

Only Ayna understood. He was the educated one. He could read and count. They all marvelled at his capacity to remember things – the names of every village ancestor going back eight generations, and his unrivalled mastery of the Koran. He had even learned some English. He knew the names of all the invaders’ aeroplanes: Osprey, the half-plane, half-helicopter, Huey, with two rotors, Apache and the AV-8 jump jets that it was said could even fly backwards. There was so much in his head – and so much more he could know. Isa thought perhaps that was what made him cry: he didn’t know if he could take his earthly knowledge with him to Heaven.

They brushed past the first poppy stalks but stayed flat to the earth. Before they had left the room, they had taken a last look at the map, the route across the huge base to their destination – the aircraft hangars. Was it yards or miles? They had no idea of the scale. Only today had the Leader let them into his secret. Don’t worry, my brothers, friends will be waiting. You will be transported.

A miracle? Isa asked.

And the Leader laughed. In a way, yes.

They lifted themselves to take their first look. Stretching from one horizon to the other, the perimeter fence looked like the border to another land. Above them in the starless sky a pair of jets thundered past, their black cut-out shapes almost invisible in the darkness, except for the twin circles of fire, low enough to shake the ground beneath their feet. In the brief orange glow of the engines Isa again saw the glint of tears on Ayna’s face. He reached out and gave his arm a squeeze – but then the Leader spoke.

‘Here we wait for the signal.’

4

They were in the open now, moving swiftly in the dark, their packs heavy with weapons and ammunition bouncing on their backs, pounding the rough dirt underfoot. They ran heads down towards the towering walls, giant mesh barriers filled with sand and topped with razor wire. Up ahead the Leader looked round every few seconds, as if any of them would dare to turn back. Isa glanced at Ayna and saw that his previously tearful face had hardened into a mask of concentration, as if he had finally found something to focus on, perhaps knowing that there was no alternative fate, nothing to do but resign himself to what was ahead.

They were now within range of the giant arc lights that swept the area round the gate, the light bouncing off the sweat on their faces. Any other day, the guards in the towers would have seen them. Loudspeakers would have ordered them to halt and identify themselves. But this wasn’t any day.

A brother will prepare our welcome, the Leader had told them. The gates will open: no guards will fire. They must wait for a signal to approach. Three flashes five seconds apart, and the same a minute later. They were all commanded to watch so no one would miss it. On the third they were to move forward, like a detachment of real ANA soldiers returning from a perimeter patrol. Never mind that they were on foot and it was night. The ANA were famous among the other nationalities for doing strange things.

Beyond the wire, the lights of the airfield shone with a ghostly glow. Even at night they appeared to shimmer, the heat of the day still rising. Below they could make out the sharp outlines of the Ospreys, the Huey gunships, Cobras and Harrier jump jets, loaded with rockets and bombs. These machines – unassailable, so the enemy believed – were their targets.

Ayna saw it first. Three flashes a few metres to the left of the gate. He tugged Isa’s tunic and Isa squeezed the forearm of the Leader.

Who is he, the man on the other side? Ayna had asked. How is he our brother if he is with the enemy?

We have many brothers everywhere, came the Leader’s reply. They are biding their time, waiting to act. As well as courage, they have great patience, which is why we will win and the glory will be ours.

Now they advanced again, in twos, as they had been instructed, like tired soldiers after a long day. But none of them was tired. Their hearts were beating fiercely. What they all knew was that this was their last march, and that the end would be soon – and spectacular.

5

Tom set a course for the gym near the perimeter of the flight line. He jogged down a street lined with rows of Portakabins occasionally interrupted by the odd ISO container. The pervasive whiff of aviation fuel hung in the air along with a thin clouding of dust. He’d known bases of all kinds around the world, but none on this scale. This was a vast fortress capable of handling an entire invasion force. Its sheer size alone should have been enough to get the message across to the enemy about who was boss round here. And despite all the talk about a phased withdrawal, construction was still going on, the runways being extended, rumour had it, so B-52s could be based there in the event of war with Iran.

Yet Tom felt its very enormity, along with its arsenal of weaponry, created a false sense of security. Last week they had deployed to a forward patrol base, under canvas; no air-conditioned gym, just a desert rose to piss in and furniture improvised from wooden pallets and the wire frames of the Hescos. At least you knew what was at stake out in the field. He preferred it to this prefabricated metal city in the desert, a giant, very costly white elephant that the bean-counters in Whitehall and Washington longed to be rid of. But despite the politicians’ proclamations of ‘mission accomplished’ and the start of a phased handover to the Afghan National Army, to Tom it didn’t look like this long war was anywhere near done.

A moonless sky hung over the camp, the moisture in the air reflecting the dull orange glow that came from the floodlights. At the end of the street of Portakabins a wide open space bordered on the USAF maintenance compound. To the left, about fifty metres away, was the South Gate, and straight ahead the gym, about another three minutes if he upped his pace. A small detachment of troops crossed the end of the street and turned towards the airfield. Just from their size Tom could tell they were ANA. Generations of deprivation and the habitual lack of decent nutrition had kept their average height several inches below that of the other nationalities. Once they had cleared he saw another figure in front of the gym, bareheaded, carrying a torch but no obvious weapon. The figure lit a cigarette, then lifted his head to blow a long plume of smoke up into the night.

Qazi.

That morning Tom had witnessed him being fêted by the US camp commander, Major General Carthage, in front of a gathering that included a number of press – quite a large number.

‘You are looking at the future, gentlemen.’ Carthage, towering over Qazi, patted him on the shoulder in a way that made Tom squirm, as if he was his pet. Qazi stood expressionless, with a faraway look in his eyes that revealed nothing.

‘Second Lieutenant Amhamid Qazi, like many in the ANA, enlisted out of patriotism and devotion to his country. As a member of the first Commando Battalion of the 3rd Brigade Quick Reaction Force he sure has shown us what he’s made of and just what the ANA is capable of doing.’

Tom had felt himself cringe even more as he watched Carthage pour treacly praise over the Afghan.

‘. . . and then his weapon became inoperable. What did he do? Did he stop? The hell he did. He. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...