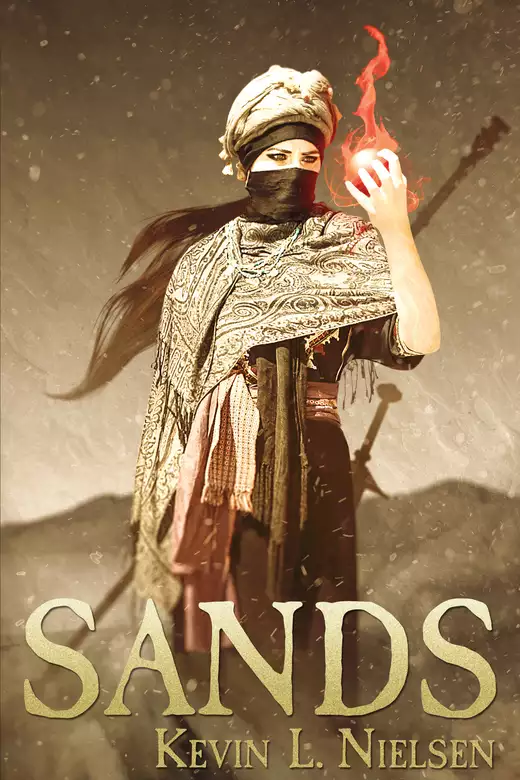

Sands

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

For nine months of the year, the sands of the Sharani Desert are safe. The genesauri-giant, flying, serpentine monsters who hunt across the desert in enormous packs-lie dormant. The smallest of their kind is able to take down a single man with ease, and the largest is able to swallow entire clans. The people of the desert have always been able to predict the creatures' appearance, but this year, the genesauri have stopped following the rules.

When the genesauri suddenly attack her clan, seventeen-year-old Lhaurel draws a sword in her people's defense-a forbidden practice for women of any clan-and is sentenced to death by her own people. Chained to a rock and left to be eaten by the next wave of genesauri, Lhaurel is rescued by a mysterious, elusive clan said to curse children at a glance, work unexplainable terrors, and disappear into the sands without a trace.

With the fate of the clans hanging in the balance, Lhaurel discovers she possesses a rare and uncontrollable power-one that will be tested as the next deadly genesauri attack looms on the horizon and the clash between clans grows more inevitable by the hour.

Release date: July 22, 2015

Publisher: Future House Publishing

Print pages: 307

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Sands

Kevin L. Nielsen

—From the Journals of Elyana

The crowd pressed close as the outcast juggler tossed flaming brands into the air. Near the middle of the crowd, three children scuffled. Two boys pushed a little girl out of the way and scrambled to get a better look. The little girl fell with a muffled shout, landing hard enough to scatter sand across the stone floor.

Lhaurel watched the children out of the corner of her eye, waiting for the parents to step in. None came. She moved to the girl’s side, gently helping her to her feet. One of the boys, perhaps no older than seven or eight years, made a face at her, but Lhaurel glared at him until he sniffed and turned back to the show. Lhaurel turned back to the girl and dusted her off. There was a small cut on one of her cheeks that bled down in a thin, red line.

“Hey,” Lhaurel said softly, licking her thumb and wiping away the blood. “It’s alright. Do you want to see the juggler?”

The little girl swallowed and bowed her head, shuffling her feet and sniffing as her nose ran.

Lhaurel sighed. Most of the children in the clan had been told to stay away from her—the clan’s bad influence—at one point in their lives. It appeared they were starting even younger now.

“Come here.” Lhaurel swept the girl into her arms and then up onto her shoulders.

The girl whooped, drawing angry glares from more than one of the watchers, but none of them said anything. Little hands fastened in Lhaurel’s bushy hair, and a little chin dropped onto the top of her head. Lhaurel smiled and turned her attention back to the performance. And for a moment, at least, the stresses and weight of the next day faded away.

The juggler gave way to a pair of acrobats, who contorted themselves into strange positions and performed stunning jumps and leaps that left the crowd gasping. The little girl laughed and clapped her hands. Lhaurel laughed along with her.

Castoffs from the seven clans of the Rahuli people, the outcasts, were typically shunned and ignored, left to wander the Sharani desert alone unless they found another of their kind. Except, of course, when there was cause for celebration. Then they were commissioned to perform.

Even under invitation, though, they were kept at arm’s length. Unwary people were sure to lose any valuables they had on hand if they let an outcast any closer.

The little girl—Lhaurel thought her name might be Kesli—tugged on Lhaurel’s hair. “Look. They’ve got red hair like you.” The girl pointed one pudgy hand at the acrobats, who bowed to the clapping audience and stepped away from the stage.

Lhaurel tugged on the girl’s foot, and she giggled, dropping her hand.

In truth, Kesli was half right. Lhaurel’s hair did have a certain reddish cast to it, especially in the sunlight, but it was a deeper shade of brown beneath. The acrobats had hair the color of fresh blood, bright and vibrant even in the dim light of the cavern in which they performed.

Not many people paused to consider the difference, though. More than one family had passed Lhaurel along based on the color of her hair. That and her height, another similarity she and many outcasts shared.

The acrobats vanished into the small group of waiting performers behind the stage, and an older woman stepped forward amidst the claps and shouts from the crowd. This woman’s hair was streaked through with white, only a few strands of brown remaining. She had been acting as the main narrator, introducing the next performance and interacting on behalf of the group as a whole. It was almost as if she were their leader, a preposterous idea. Even the Matron of the Warren had to bow before her own Warlord. Yet Lhaurel admired the outcasts for it.

In the back of Lhaurel’s mind, seeing this outcast woman leading the tribe only made her that much more nervous about what lay before her.

“Wasn’t that something?” the woman said, her voice a scratchy, grating sound like the wind against sandstone rocks during a storm. “We will now be graced with the story of a great warrior, a man of great stature and strength. Gavin, master of lore and legend, will tell the tale of Eldriean.”

She raised her hands wide, and a young man stepped forward, garbed in simple, dusty robes. He adopted an easy, practiced pose just slightly off from true. His red-brown hair fell casually in his eyes, but he stood stiffly, like he was afraid of something. Or he was simply nervous. If she were the one on the stage, she’d be stiff as well. And trembling on the inside.

The crowd applauded. Several of the younger children pushed forward through the crowd in an effort to get closer to the storyteller. Stories were rare, and this one was a favorite.

Lhaurel leaned forward slightly, though not enough to unseat Kesli. In her seventeen years, she’d only heard the story one other time, and it had been so long ago she’d forgotten much of it.

The man, Gavin, kept his eyes forward, focused beyond the crowd at a distant point on the wall behind. When he spoke, there was no quaver in his voice. It resonated and echoed off the cavern walls as if a chorus of men were speaking.

“The Salvation War, War of Recovery, The Deliverance. It went by many names. In the last years of the long, bitter struggle, Eldriean became leader of the Rhiofriar, greatest of the three clans.”

A focused hush fell over the listeners. Even the small children fell silent.

“It was a happy time for the Rhiofriar, for the Enemy had abated its furious onslaught. The clans could take a few months, mere moments against the span of years of death that came before, to breathe once more. To have a few moments of peace.

“But the blood of past deaths rang heavy in Eldriean’s ears, a clarion call to arms. He rode forth to the Lord’s Council on the back of the Winds, his mighty Weapon at his side, won from an Enemy slain in battle. With a voice of thunder, he claimed leadership of all the clans, not just his own. He demanded their fealty and their strength. He drew forth his Weapon and brandished it in the face of those who opposed him. One, Serthim, stood against him longest, but all fell away, bowing to his might. They surrendered to his glory.”

The man paused, letting the silence grow heavy with weight. Emotion roiled in the cavern, curiosity mixed with confusion. Who was this Eldriean? And the Rhiofriar? No such clan existed.

“The hordes came in waves,” Gavin continued, “from the earth and from the air, leaving destruction and death in their wake.”

“The genesauri!” Kesli whispered. Lhaurel felt her shudder in fear. A matching one worked its way into the pit of Lhaurel’s own stomach.

“Yet Eldriean brought the clans together in unity in the one place where life still clung. The clans met the enemy there upon the cliff that surrounded this place of lush fertility. There they ringed the walls with bodies and with flesh, armed with lances and swords and spears and magic and will. There they faced the final charge. There the Weapon that so much sacrifice had earned was unleashed in full at long last, unleashed in all its might and glory and horror. There they found victory and defeat. There they found their salvation. And their destruction. There upon the cliffs.”

Gavin waited, his eyes growing unfocused. His hands shook at his sides, and he clenched his fists into balls. Behind him, the older woman made a small grunt.

“Eldriean fell there, upon the cliffs,” Gavin continued, his voice so soft that Lhaurel had to strain to hear. “Betrayed by Serthim, who had never truly bowed. His mighty Weapon, which had rallied the clans and unified them under one rightful King, pierced Serthim there, slamming the traitor into the rocks even as he fell, sealing the fate of the Rahuli.

“Leaderless, left to fight the enemy on their own, they became lost and broken. Three tribes became seven—and the outcasts. But it is said Eldriean’s Weapon lies there still atop the cliffs of the Oasis, there for the time of great need when the clans shall once again need a King.”

For a moment after Gavin stopped speaking, the silence seemed a living thing, an entity unto itself.

The man stood upon the stage, head bowed and fists clenched, as if telling the tale somehow left him afraid. Or maybe angry. Lhaurel couldn’t decide which.

A bark of laughter shattered the ethereal blanket that had covered them all.

Jenthro, Warlord of the Sidena, stepped forward. “And every year in the Oasis, at least one of you fools dies trying to scale those rocks and find it. Now that is a performance I like watching,” he said, raising one hand and spreading it before him.

Behind him, several people laughed. Atop Lhaurel’s shoulders, Kesli giggled as well, though Lhaurel wasn’t sure the girl knew what she was laughing about.

Lhaurel herself maintained her silence. The man was an outcast, but he was still a person.

“Wasn’t it just last year there were two of them who tried?” Taren asked. He was an older warrior, the effective second in command behind Jenthro. “I think I remember watching that one. A husband and wife, I recall. One of them tried to fly when they fell, flapping his arms like a bird until he hit the sand.” He mimicked flailing arms, and the Sidena laughed again.

The man on stage, the youth, really, shook with suppressed anger. Lhaurel was sure his nails were digging into the flesh of his palms. The outcasts who had already performed were stony faced or else turned away, backs stiff.

Only the older woman seemed unfazed. She stepped back up to the stage and smiled sweetly down into the jeering faces. With one hand she pushed the young man back in the direction of the others. He retreated with reluctant steps, leaving her alone on the stage.

“Mighty Sidena,” she said with a bow that a woman her age shouldn’t have been able to accomplish with such alacrity and grace. “We will take our leave now. If you would kindly provide us our payment, we will leave you to your festivities.”

Lhaurel winced at the reminder. As much as she enjoyed the performers, she would rather they not be here at all.

No, I won’t think about it. Not now.

Jenthro laughed and gestured with one hand. “Three goats, I believe.”

A disturbance arose at the back of the crowd, followed by renewed laughter. A younger warrior came forward, pulling the leads on the three goats. Lhaurel felt a moment of pity when she saw the creatures.

Scrawny and obviously sick, the goats were in such bad health they were likely only a few moments away from being culled from the herd. Lhaurel could count the ribs on all three of them. One even had a large, festering sore on one flank that was causing the animal to limp.

Lhaurel felt a moment of simultaneous anger and pity warm her chest. The goat and sheep herds were a large part of what sustained the Sidena. They were cared for, fed, and looked after with more care than some of the children. These animals had been purposefully underfed and neglected to mock and demean the outcasts.

It was vain, foolish posturing. The act was one she should have expected. One more strike against a clan she would never call her own.

“Three goats,” Jenthro said with a bow much less graceful than the lady’s had been, “as promised.”

The woman accepted them with another bow, not even raising an eyebrow at the condition they were in. She was an outcast. They were used to such treatment. At least they got paid at all. Other clans may have chased them out at the point of a sword.

Lhaurel admired the grace the woman showed in the face of such hostility, a grace Lhaurel wished she herself were able to imitate. She’d thought about joining them before but had always given up on the idea. Life in the protection of a large clan was better than life as a clanless nomad.

Yet, as the small group of outcasts gathered up their possessions and left the warren, pulling wide-wheeled handcarts and escorted by a half-dozen Sidena warriors, Lhaurel couldn’t help but wonder if her life was really any better off than theirs.

“Our lush, arboreal verdence lays desolate, crumbling from life to dust. Life is dissolution.”

—From the Journals of Elyana

Lhaurel paused at the intersection of two passages, trying to decide if she should go back and accept her pending marriage or chance the desert sands on her own. If she was honest with herself, she knew there wasn’t really much of a choice. She’d never survive the sands alone, not with the Migration coming in just a fortnight’s time, but that didn’t stop her from trying to avoid the bonding ceremony anyway. To give up was to condone the act, which she didn’t.

Part of her toyed with the idea of running away and joining the outcasts like the group from the night before. But—

She took a deep, steadying breath as the sound of voices echoed down from the passage ahead of her, and she began walking at her normal pace, careful not to appear as if she had been running. The stitch in her side throbbed, reminding her of her lie.

A crowd of women appeared in the passageway.

Lhaurel mentally sighed, succumbing to the inevitable. They would have found me eventually anyway.

“Lhaurel,” the woman at the front of the group said in an exasperated voice, “there you are! We’ve been looking everywhere for you! Didn’t I tell you to meet me by the greatroom?”

Lhaurel inclined her head in respect, which also hid the grimace that crossed her face.

Marvi was a large woman, as equally intimidating by her size as by the blue shufari at her waist that marked her as the Warlord’s wife. The Matron of the Warren, Marvi could tan the hide off of anyone with either her hand or her tongue as easily as a sandstorm stripped the flesh from a body.

“Your pardon, Matron,” Lhaurel said as women with yellow shufari began to usher her down the hall with impatient clucks or gentle prods, “I needed to be alone for a moment to—to get ready. I didn’t mean to cause you stress.” Only years of practice kept back the bitterness from her voice.

Marvi snorted and rolled her eyes, brushing back her long black hair with an irritated flick.

“As well you shouldn’t. If today weren’t your wedding day, I would send you out with the children to tend the sheep and hunt for mushrooms. And Saralhn’s no better. She was supposed to be keeping track of you. I put her to task working the salts.” She sniffed. “Your head is as full of sand as a genesauri’s nest. Why, just this morning I was telling the Warlord—may he ever find water and shade—that you’ll need a strong hand to calm your vagrant spirit. He just nodded in that flippant way of his. As if I hadn’t carried his children for the last twenty years or made sure the warren had food to eat and water to drink. Despite him, sometimes.”

Even Lhaurel flinched at the words. Marvi was the only one who could get away with speaking so ill of the Warlord, and even for her it was dangerous. If her husband hadn’t been so indulgent, he could have ordered her death just for referring to his nod as “flippant.” Lhaurel grated at the irony of Marvi being the one to always punish her for acting unwomanly. Lhaurel had often found it to be true: those who most vehemently supported an ideal were often the ones to most egregiously and consistently violate it. As it was, what Marvi said was true, at least insofar as taking care of the warren despite the Warlord was concerned. She never let his temper get in the way of getting things done.

Lhaurel did feel guilty about getting Saralhn into trouble again, though. She hadn’t known Saralhn had been appointed to watch over her. Likely Saralhn had known Lhaurel needed the mental and emotional break and had let her go, knowing full well she’d get in trouble for it. That was so like Saralhn. Lhaurel made a mental note to thank her for it later. After she apologized.

“You’re as wayward as a Roterralar, child,” Marvi continued, ushering the procession through a series of passages normally reserved for women who wore a purple shufari. “Maybe one of the older, widowed warriors would suit you best. Sands knows I’ve had my hands full trying to find someone willing to take you after everything you’ve done.” Lhaurel didn’t have to see Marvi’s face to know the Matron was rolling her eyes toward the heavens. “Taren would have you broken and gentled within the week.” Her voice grew soft at the end, almost a whisper, and she grimaced.

Lhaurel couldn’t suppress a scowl of her own. If she had to get married at all, couldn’t it at least be to someone who wasn’t old enough to be her grandfather? Part of her gave a mental shrug. What difference did it really make? The choice wasn’t hers either way.

The young women around her broke out in whispers, each suggesting a potential match among the eligible bachelors of the clans. Taren was, surprisingly, one of the least objectionable choices.

“Enough of that now,” Marvi said, noticing Lhaurel’s scowl. “You will learn your place. Just as your sisters have.”

Lhaurel had always hated how all the women of a certain age were referred to as sisters, even when there was little, if any, relationship between them. She had no true sisters, and the women in her own age group found her odd, almost as odd as she found them. Most of them were around her, wearing the yellow shufari that marked them as bound to a man, wedded within the last year. After that, they would wear the brown until their husbands attained a high enough status for their wives to wear the purple. Or, like Marvi, their husbands became the Warlord. Then they would wear the blue.

Lhaurel was as different from them as it was possible to be. She stood a full head taller than most of the Sidena woman, tall and thin and straight like a pole, all angles and bone without much of a figure to speak of. Where they were olive skinned with dark hair and dark, ovular eyes, Lhaurel was fair of skin, was covered in freckles, and sported an unruly mane of bushy hair the color of new-formed rust.

Sisters indeed. Well, she counted Saralhn as a sister, so they weren’t all bad.

The procession led her to the bathing chambers, where steam wafted up from the salted hot spring vents. The water was unsuitable for drinking, but it served perfectly for bathing or washing out clothes as long as you didn’t mind the fine grit of salt that was left behind. Honestly, it wasn’t much different than having your clothes or body covered in sand. Either way you remained itchy.

The salt springs were the pride of the Sidena, and the salt harvested from them was a staple of trade for the clan when they were in the Oasis. The shallower pools, farther down in the caves, were a stable source of drinking water once the processing was completed. Lhaurel didn’t understand it completely, but it involved capturing the steam. Somehow that produced non-salty drinking water. Or something like that.

Lhaurel stripped and stepped into the hot water while listening to Marvi prattle on. She smiled when the dirt, sweat, and sand were washed away, leaving her skin feeling clean and smooth. As she slipped beneath the water to rinse her hair, though, Lhaurel couldn’t help but suppress a nervous little shiver that crept up her spine. She was getting married today. A small part of her was excited and nervous all at once. Another part of her, the larger part, felt an overwhelming sense of defeat. She’d have to give up so much. Her independence, the freedom to clandestinely do things women were not supposed to do, was at an end.

“You know, you really shouldn’t provoke the Matron like that, Lhaurel.” A soft voice said when Lhaurel broke the surface of the water.

Lhaurel opened her eyes. Marvi and most of the other women had departed while she had been under the water, leaving only one behind. Saralhn, the closest thing she had to a friend. As was custom, Saralhn, the most recently wed among the women, would prepare Lhaurel for her own union.

The short woman frowned at her, arms folded beneath her breasts. “Running off like that on the morning of your wedding.” Saralhn held out a towel so that Lhaurel could dry herself off. “Why do you always do that?”

“You know why, Saralhn,” Lhaurel said, taking the towel.

Saralhn only sighed and shook her head.

Lhaurel ran the rough towel through her hair, making it stick out at odd angles over her head. “Thanks for letting me go anyway. I didn’t mean to get you into trouble.”

Saralhn smiled and helped dry Lhaurel off with another towel she took from a nearby stack.

“I don’t see that you have anything to complain about,” Saralhn said after a moment, a small note of envy creeping into her voice. “If you really do end up with Taren, you’ll jump straight to the purple after your year with the yellow.”

“We’ll just have our children call him grandfather instead of father,” Lhaurel said, making a face. “It’ll be wonderful.”

“Oh, Lhaurel, why do you have to fight so much? This is our life. It is a good life. Being married, being a woman, they have their own rewards. Besides, no matter how much you fight it, there’s no way out.”

Lhaurel maintained her silence as she finished drying herself. Saralhn was right, of course. There wasn’t any way out, and that’s what Lhaurel hated more than anything. Her only purpose, according to the clan, was to serve her husband and the clan by producing more children and tending to womanly tasks. All the other women in the clan accepted this and seemed to find some measure of happiness in fulfilling that purpose. Lhaurel sometimes wondered if there was something wrong with her since her thoughts dwelt on things generally denied to women. Mostly she wondered what was wrong with them.

Saralhn turned and retrieved a small box from a nook in the wall. Actually, it wasn’t a box at all. It was something wrapped in a piece of white cloth.

Lhaurel looked a question at Saralhn, who gave her a small smile as she handed Lhaurel the bundle. “It’s not much, but it was the best I could do.”

Lhaurel slowly removed the cloth, revealing a thin white comb made of bone, teeth set wide apart. With Lhaurel’s thick hair, the wide teeth would be a welcome relief.

“Oh, Saralhn,” Lhaurel said, voice catching. “Thank you.”

Saralhn held up a hand to silence her, a faint smile on her lips. “I understand, Lhaurel. Let’s just pretend, for now, that I’ve convinced you to be happy and that you actually are, okay?”

Lhaurel smiled through the tears in her eyes.

No further words were exchanged between them. Not as Saralhn combed and braided Lhaurel’s hair. Not when Saralhn garbed her in the robes of a bride. And not when the gaggle of young, married women returned and hurried her away. None were needed.

* * *

Lhaurel waited impatiently in the exact center of the greatroom, thick leather ties hanging from her left wrist—the bonding ties. Her hair was arranged in a beautiful net of braids and beads that spread down her back like dunes. She fingered her blue dress for perhaps the hundredth time, feeling the fine material and wishing she could scratch without appearing nervous. She would have preferred the dress be green, but blue was the traditional color of a bride.

All around her, the clan stood in neat rows, warriors in front, women and children behind. She stood alone, open and exposed.

The reality of it all hit her with the force of a storm wall. She’d put on a brave face for Saralhn earlier, but she had been right. There was no way out of this. Standing here in front of everyone, waiting for her first glimpse of the warrior to whom she would be bound—this was the beginning of the end.

She was devoid of shufari. It was the only time in a woman’s life that her status was not openly displayed about her waist. In that moment she was nothing, a woman devoid of identity and life until her new husband arrived. When he did, she ceased being an individual and started being a possession. It was her last silent moment of freedom.

Lhaurel sniffed and swallowed hard, though her mouth was suddenly dry. She ground her teeth together, refusing to cry. Crying was a waste of pure, precious water. Instead she stood erect and raised her chin, putting on a smile. She saw Saralhn standing behind her husband, but the woman’s eyes were dutifully looking elsewhere. Toward where the bridegroom would enter.

Lhaurel glanced around the room at the assembled clansmen, unable to look where they were looking. Maryn stood next to her husband, Cobb, the older couple looking stern and resolute, as always. Portly Jerria, with her gaggle of children around her, snatched one of them as they ran by and put the offending child back in line where she belonged. Lhaurel had spent nearly five full fortnights with that family before Jerria had asked Marvi to pass her along to another one.

A small group of children, all younger than eight years old, stepped forward as an older woman produced a set of thin reed pipes and began to play. The melody was a familiar one, played at every bonding ceremony. The notes of the song echoed in the large room, the effect being a broken duet. A call and then a distant echo. The children began to sing, though Lhaurel couldn’t distinguish the words. A wash of jumbled emotions spread through her, so mixed up Lhaurel couldn’t begin to pick out any one in particular.

From behind and to the left of the assembled crowd, hand drums began to pound. The sounds rang out in the sandstone chamber, echoing off the walls and amplifying the notes of Lhaurel’s pounding heart. Beads of sweat formed on Lhaurel’s brow as the crowd directly across from her parted and the Warlord led his procession, eight warriors forming a tight ring around her chosen husband.

Lhaurel tried to catch a glimpse of the hidden man, but the warriors around him stood too close together for her to make out anything but the standard brown of cloth and leather. A hard look from the Warlord, who had noticed her rebellious act, dropped her back on her heels. But she refused to lower her gaze.

The Warlord cut an imposing figure, full of hard lines and with a face as impassive as stone. His graying hair was pulled back into a topknot by a simple cord adorned with a metal pin shaped like a sword. He walked with the grace of a warrior but the poise and air of one who had lived with authority as a mantle since youth.

Growing up, Lhaurel had often thought the man arrogant. Looking at him now, she revised her earlier opinion. It wasn’t arrogance. It was condescension. She almost took a small step backward as his gaze fell upon her once again. She realized that she was chewing on her bottom lip and stopped herself.

The crowd around them watched the ceremony impassively as the procession passed through a hallway of crossed swords and then parted, reve. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...