- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

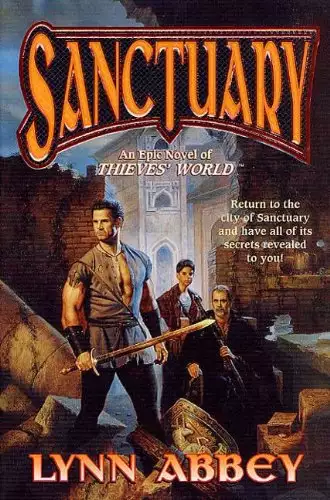

From the Bestselling Fantasy Adventure Series, Thieves' World (tm)

Created by Robert Lynn Asprin & Lynn Abbey

Return To The City That Would Not Die!

Return To Thieves' World!

Return To Sanctuary!

Thieves' World was the bestselling and first of the shared world phenomenon, selling well over a million copies of anthologies detailing the exploits and intrigues of the high-born and low-born denizens of Sanctuary, a city that has seen many masters.

The Age of Ranke and the reign of Kadakithis, the occupation of the Beysib, the war of the gods and indeed the erstwhile Renaissance are now all in the past. Memories of heroes and villains, glory and savagery have all been relegated to the shadows of yesteryear as present-day residents once again apply themselves to the task at hand: survival.

Only Molin Torchholder, architect of Sanctuary's glory and master of her secrets. knows the whole truth, but he is dying . . . He must hold on until he can pass along the city's hidden history of empires come and gone and blood shed for reason and naught. Aiding him are a lowly laborer named Cauvin, himself a survivor of one of the city's darkest moments, and a young boy named Bec.

So many secrets and so little time. And as Molin's chronicles of the past unfold, even darker forces return, an evil that jeopardizes the very survival of a city that until now has always refused to die.

Sanctuary - An Epic Novel of Thieves' World ushers in a whole new age of tales, a whole new age of Thieves' World.

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: April 14, 2003

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 480

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Sanctuary

Lynn Abbey

Chapter One

A full moon shone over Sanctuary, revealing boats in its harbor, dwellings within and without its coiled walls. The city appeared prosperous, but Sanctuary always shone brightest at night. In sunlight, a man standing on the eastern ridge overlooking the city would see that the largest boats tied up along the piers were rotting hulks, that roofs were missing all over town, and the great walls had been breached by neglect in several places.

Sanctuary could have looked worse and had many times during the half century that Molin Torchholder had--however reluctantly--called it home. Gods had fought--and lost--their private wars on Sanctuary's streets, but the city went on, resilient, incorrigible, just possibly eternal. Its citizens repelled catastrophe as readily as they squandered prosperity. Time and time again, Molin had watched fire, storm, plague, invasion, and sheer madness sweep through the city, carrying it to the brink of annihilation, only to ebb away, like the tide shrinking from the hard, black rocks wrapped around its harbor.

And should Molin Torchholder call himself a citizen of Sanctuary?

In the morning years of his ninth decade, no one would deny Molin the right to call himself whatever he wished. He preferred to think of himself as Rankan. Born in the Imperial capital, raised by priests of the war-god, Vashanka, and risen to the heights of their hierarchy before his twenty-fifth birthday, Molin Torchholder had been marked as a man with a glorious future. Then he'd come to Sanctuary, a city on the edge of nowhere, a city so far removed from the Imperial Court of Ranke that an insecure emperor had thoughtit a safe place in which to exile an inconvenient half brother when a sudden attack of conscience stopped the fratricide the Imperial advisors--including the high priests of Vashanka--had suggested.

I'll be here a year, Molin had thought the first time he'd ridden down this road. One insufferable year, then he'd be back in Ranke, accumulating power, wealth, and a legacy for the ages. His god had had other ideas. Molin's god had a taste for blood and chaos and once He'd gotten a taste of Sanctuary's particular squalor, Vashanka couldn't push the plate away.

Vashanka had amused Himself with children, thieves, and the pangs of lust. The war-god of the mightiest empire in the world had made an immortal fool of Himself for years. Spurred by immortal embarrassment, divine powers both great and small had allied to erase Vashanka's name from the white-marble lintel of His own temple--from the temple Molin himself had raised in His honor. Reduced to little more than an itch on the world's behind, the great Vashanka had slunk out of Sanctuary on a night very much like this one more than forty years ago.

Molin hadn't felt his god's departure until the next morning when he'd encountered an indescribable absence during his daily prayers. Vashanka's come to His senses and returned to Ranke; Molin had thought, little realizing that Vashanka had gone not home, but into exile. Worse--the divine powers that had run Vashanka out of Sanctuary had condemned him--him!--to remain within its walls.

From the beginning Molin had loathed everything about Sanctuary: its wretched, soggy climate; the brackish taste of its water; and, especially, its citizens. He swore he could never be reconciled to an unjust fate; then the moon would rise and he'd be drawn to the roof above his palace apartment--or find himself delayed on the East Ridge Road. His thoughts would wander, and Sanctuary would take his soul by surprise, flexing its claws, reminding him of what he tried so hard to forget: This place, and none other, was home.

Footfalls drew Torchholder's attention away from the rooftops of Sanctuary. He turned in time to see his escort, a man scarcely a quarter his age, climb out of the roadside ditch. Atredan Larris Serripines' face was paler than the moon and shiny with sweat but, on the whole, he looked a good deal better than he had when he'd staggered into the grass.

"Better now?" Molin asked pleasantly.

Atredan favored him with a scowl. "So much for Father's Foundation Day Feast."

In another time and place, Lord Serripines' second son might have amounted to something. He had the golden hair and hazel eyes of a true Rankan aristocrat, an amiable personality, and the sense not to get caught when he succumbed to temptation. Lesser men had ruled well in Ranke. But in Sanctuary, a generation after an eastern horde had brought fire, rape, pillage, and death to the Empire's heart, Atredan was doomed to ambition without prospects.

No commemoration of the Imperial Founding, however precisely observed, could change that.

Molin dug into his scrip and found a sprig of mint twisted with other herbs, which he offered to the younger man. "I think you'll find it settles what's left and takes the taste away." When one indulged as the Imperial court in its prime had indulged, one never forgot its remedies and kept them forever close to hand.

Atredan had refused the digestive when Molin had first offered it, but took it gratefully now and chewed hard. Within moments his face had relaxed.

"Gods all be damned, Lord Torchholder, I can't believe any emperor has ever sat through a meal like that! The food. The wine--especially that wine. Anen's mercy, what did my lord father put in it this year?"

Never mind that Anen was the Ilsigi god of vineyards and anathema to the Rankan pantheon, Atredan had a valid argument.

"Honey," Molin replied with an honest sigh. "A comb of Imperial honey, straight from the Imperial hives, the Imperial garden, and the Imperial pantry. The genuine article--or so he told me. Very rare these days."

"Very expensive," Atredan corrected. "Very old, very spoilt, and fit only for swine or my lord father's Foundation Day table."

"That is not for me to say," Molin said diplomatically and--because he was, among many other things, an accomplished diplomat--he made it clear that he would have agreed with the young man, had it been necessary to do so.

Diplomatic nuance was wasted on the Serripines' cadet heir. "Did you actually drink that swill?"

"I'm an old man, Lord Larris, and my palate is as old as the rest of me. Swill or ambrosia, it all tastes the same now--Yet, I am sure the wine we drank in Ranke was not so sweet ... or gluey. And neither did we ferment it ourselves. Truth to tell--we seldom drank Imperial wine, with or without Imperial honey. All the best vintages came by ship from Caronne. They still do, I suppose, but not to Sanctuary. Have a care for your lord father. He was a babe-in-arms when Ranke fell. He dreams of Rankan glory, but he doesn't remember it."

Atredan muttered words too soft and slurred for Molin to catch. The indignities of age! His reputation had been built on his eyes and his ears. Time was when no word or gesture had escaped his senses; that time was gone. It was true that younger men still complimented him and relied on his advice, but they had no idea how much of his edge he'd lost.

Or how tired he had become.

"Come," he urged his escort, "it's time to get me home to my bed."

"You could have stayed at Land's End. My lord father loves nothing better than to have the Lord Torchholder sleeping beneath his roof. A veritable hero and not merely of Sanctuary--as if Sanctuary could nurture a true hero--but of the Empire."

"For all the good my heroics have done me." Molin chuckled. "After two nights beneath your lord father's roof, I've told all the stories of Imperial glory that I can remember. I've drunk his wine and lit his bonfire. The Imperial ancestors have been properly honored, a new Imperial year is safely begun, and I'm ready to go home."

Atredan cocked his head in the moonlight. "You think we are all fools, don't you, Lord Torchholder? My father, the Rankans he shelters at Land's End ... me."

"All men are fools, Lord Larris--you, me, your lord father, and all the men and women beneath his roof. The nature of men is foolishness. Never forget it."

"But the Serripines more than others, because Father believes Ranke will be mighty again, and that will never happen."

"Only a fool says 'never' when speaking of the future."

"There's no future for the dead. There is no future, not for us,not for Ranke. We're like fish in a weir. We sing praises each time it rains, but the fact is, we're trapped, and if the rains don't come, we die. Only sooner, rather than later."

Molin gave Atredan a second look--he'd never before suspected that the young man had a bent for philosophy, and although he generally agreed with Atredan's dreary assessment of Rankan prospects, he offered up a scrap of encouragement: "Sanctuary's a coastal town, my boy. The tide comes in twice a day, no matter the rain. A man may drown, but he'll surely never shrivel."

"My lord father has shriveled. He hasn't set foot in Sanctuary since the Bleeding Hand killed my mother. He lives in his own world at Land's End with his back to the sea, waiting for an army that will never come to take back a city that was never his."

Molin didn't like to talk about the years when the Dyareelan fanatics had ruled Sanctuary. Neither did anyone who'd managed, somehow, to survive. The Serripines had gotten off lightly, retreating behind the walls of their fortresslike estate. But Molin would never say that to a son who'd seen his mother disemboweled, nor to her shattered husband. He temporized instead. "Your lord father feels obligated to comfort those whom the emperor has abandoned."

And, in truth, it wasn't Lord Serripines who made each Land's End visit feel like an early trip to the boneyard. If the sack of Ranke had been the most unexpected event in Molin's lifetime, the transformation of the Sanctuary hillsides from scrubland to fields and meadows should be counted a close second. The Serripines paterfamilias might have his head in the clouds where the Imperial past and future were concerned, but in the present he was a shrewd man who knew what to plant and when and--most important--who would pay the most once the fields were harvested.

Lord Serripines would have preferred to sell his harvest to Ranke--for a profit, of course--but there was no one along the eastern coast who could match the bids made in the resurgent Ilsig Kingdom to the north and west. Lord Serripines practically, but reluctantly, listened to his head, not his heart, and sold his harvest to Ilsigi sea captains, who sold it again to men who no longer paid tribute to the emperors in Ranke. Then, to assuage his guilt, Lord Serripines opened his estate to an ever-growing community of Imperial exiles and freeloaders.

The irony was not lost on Molin. With few exceptions, the elder Vion Larris Serripines was the most successful Rankan to dwell in--or near--Sanctuary in decades. He was also the unhappiest man Molin had ever met--which was a dubious accomplishment all by itself--but worse, to Molin's jaundiced eye, was Lord Serripines' willingness to shelter any noble-blooded Rankan who washed up in Sanctuary's harbor.

Indeed, two nights at Land's End were more than enough. Molin almost pitied young Atredan and his elder brother, Vion, coming of age in their father's bleak shadow.

"You should thank me, Lord Larris." Molin changed his tone and thirty years dropped from his bearing.

"For what?"

"For giving you an excuse to leave before the bonfire was burnt down to ashes. Lord Serripines would never have agreed, and a son must obey his father."

Atredan grimaced. "My lord father doesn't understand--our future, what there is of it, is bound up with Prince Naimun, and tonight the prince will be in need of a friend's ear. Better it were my brother escorting you back to the palace and Naimun's table, but there's no escape for Vion."

Molin couldn't resist a jab at the youth's defenses. "Naimun's table or his upper room at the Inn of Secret Pleasures?"

The young man contrived to keep his pale cheeks from darkening, but his darting eyes gave his secrets away quicker than his tongue. "You are mistaken, Lord Torchholder."

"I think not, and I care not. The Inn's whores are clean enough, but not tonight, Lord Larris. If you have Naimun's ear, tell him to stay at home. There's apt to be trouble, and the Inn's guards won't withstand a visit from the Dragon."

"Pox on Arizak per-Arizak," Atredan said boldly, giving the Dragon his proper name. "Sweet Sabellia's tits--what brings the Dragon and all the rest of the Irrune to Sanctuary today of all days?"

"The Irrune are a gathering people," Molin answered mildly. "They're entirely unlettered. How else are they to communicate amongst themselves if they do not gather?"

"But not in Sanctuary and not in such numbers. I woke upyesterday morning, looked over the wall, and saw the whole damned Irrune nation riding down the road."

"The Irrune come together around their chief. Arizak's their chief, and this year Arizak's in Sanctuary because this year Arizak's leg is rotting and he can't sit his horse. As long as Arizak was out in the hills, the Dragon was confident of his inheritance, but since Arizak's butt has settled on a silk cushion instead of a saddle, the Dragon began to worry. His mother, his uncle, and the rest of the riders are worried, too, so they've followed their favored son here in number to make certain that Chief Arizak doesn't forget who he is, or more importantly, which son he's named to succeed him."

"Prince Naimun doesn't give a fig for the damned Irrune. He wants Sanctuary."

"So does the Dragon, just not in the same way. The Dragon wants the city's wealth, its wine, and its women--" Molin paused for effect. "Well, perhaps the half brothers do each want Sanctuary for the same reason, but Naimun is so much easier to distract."

"It is not a crime, Lord Torchholder, to drink with a prince," Atredan asserted, showing more spine than Molin had expected.

"No, indeed it is not. Nor is it a crime to call Naimun a prince when he is no more than the eldest son of his father's second wife--unless the eldest son of Arizak's first wife is about and your man gets himself killed in a whore's bed."

Atredan had the sense to look embarrassed. "His friends look out for him."

"And that, of course, is why you want to be in Sanctuary to-night--to look out for your friend. So be it. Naimun's weak and biddable and you think that makes him an ideal ruler. You're wrong in more ways than I can count, so be that, too. But think, if you dare, about loyalty--"

"I am loyal, Lord Torchholder." Atredan lowered his voice then raised it as his indignation swelled. "I am loyal to my father, to my brother, to my family, to my emperor--should he come to claim my service--and I'm loyal to Naimun."

"Of course you are, Lord Larris--but to whom is Naimun loyal? And why?"

"Don't play with questions, Lord Torchholder," Atredan bristled. "If you suspect Naimun can't be trusted, say so."

Molin waved the young man's anger aside. "Did I say that? Did I say that Naimun can't be trusted? Did I say he wasn't loyal? What I am saying, Lord Larris, is that while you may, indeed, be Naimun's friend and, no doubt, loyal to him, do not think for one moment that you are the only man--or woman, for that matter--in Sanctuary who's figured out that our Naimun follows flattery. Trust Naimun, if it pleases you, cultivate his love and his loyalty, but be damned wary of your companions within his charmed circle."

Atredan could not have looked more displeased if he'd had a plate of worms set before him and his father's undrinkable wine to wash it down. "Is that what this is about--the great Lord Torchholder dispensing advice on the road to Sanctuary? You're wasting your time, old man. I know everything I need to know about Naimun and the Dragon, their father, and every other Irrune who matters, and I learned it without your help or my lord father's, either."

He'd hoped for a better response, but Molin was too much the diplomat to reveal his disappointments. "Then, forgive an old man who's seen too many men fail because they forgot to watch their backs."

"When Arizak's gone, Naimun will bring Rankan rule to Sanctuary--without the emperor, of course, and without the Dragon. It's all been settled. I'd think you'd be pleased, Lord Torchholder. Isn't that what you had in mind all along?"

"Of course," Molin agreed, and the words weren't utter falsehood.

The laws of Ranke, when wielded by a strong, yet subtle, ruler were worthy of admiration. Molin would like to see Rankan law return to Sanctuary, but Naimun was neither strong enough nor subtle enough to do so. There was a man in the palace whom Molin liked better for the task--a boy, actually: Raith, Naimun's brother and the youngest of Arizak's sons. Raith had it all--the strength and comeliness, the quickness of mind, the flair for leadership and decision. What Raith lacked was experience. He was all of sixteen and needed another four years, three at least, before he could lay claim to the palace.

Damn Arizak for getting drunk and falling off his horse!

"Come," Molin said with unfeigned weariness. "An old manneeds to get moving if he's going to see his own bed before midnight."

Molin set the pace, which was slower than he would have liked--another concession to age. He relied on a staff for all but the shortest walks. The wood was gnarled and blackened and older than Molin. He'd found it in a palace storeroom and had no idea to whom it had once belonged. Probably a prince or priest of the Ilsigi; they rarely went anywhere without some symbol of authority clutched in their hands. Molin had made a few improvements. He'd burnt down the shaft and hidden Sanctuary's Savankh--the scepter with which an Imperial prince-governor ruled an Imperial city--in the tunnel. As an instrument of justice, a Savankh drew the truth out of a man, will he or nil he. The Savankh had transferred its power to the staff, but Molin, like the princes and governors before him, was immune to its sorcerous power.

In competent hands, the blackwood staff was a serviceable weapon, and, despite their years, Molin's hands were competent. He'd gotten his war-name, Torchholder, in part because of a willingness to use whatever object lay closest to hand when he fought. His strength had ebbed a couple decades earlier and his balance was going, too, but his instincts remained sharp, and the Savankh wasn't the only trick hidden beneath the staff's amber finial.

But it was a staff, a plain ordinary staff, that Molin needed as the road widened, and the iron-reinforced Prince's Gate loomed ahead. He'd been thinking with his heart, not his head, when he'd decided to return to Sanctuary. Night travel was harder on the eyes and every other part of a man's body. At the very least, he should have insisted on a pony cart; he'd given up riding not long after his seventy-fifth birthday.

"They're drunk again," Atredan grumbled, and pointed up at the guard-porch atop the gate, where no men could be seen keeping watch.

"Pull the cord anyway."

Atredan reached into shadow and hauled on a thick rope. A bell clanged within the tower. Molin, who remained in moonlight, watched for movement on the roof or any of the tower's barred windows. He saw none.

There were other ways into the city, ways that didn't involve visiting the west gate on the opposite side of the town. A three-foot-wide breach lurked behind rubble a mere thousand paces to the north. Molin would have preferred the gate, for obvious reasons, but he knew the path to the breach and had used it only a few months back to trap a smuggler who'd overreached herself.

Ever the master and merchant of knowledge, Molin would give Atredan the opportunity to lead him to the breach, to see if the younger man knew the path. The youth gave no indication he knew the path--though surely he knew that Sanctuary's walls were not a solid, impenetrable ring. He tugged continuously on the rope, setting up a din within the tower.

At length, a small, firelit opening appeared in the wall.

"'S'locked," the guard said in the coarse Ilsigi dialect that passed for Sanctuary's common language, a dialect almost everyone referred to as Wrigglie.

Molin's native language was the pure, elegant, and nuanced Rankene of the Imperial court at its height. He spoke a handful of other languages as well, but he dreamt, sometimes, in Wrigglie, and suffered a headache every time. Wrigglie was a rapid-flowing speech, punctuated with silences--as though invisible hands had suddenly squeezed the speaker's throat. At its root, it was the language of the Ilsig Kingdom some two hundred years earlier, but it had matured--or rotted--far from that root.

"We know it's locked, pork-sucker," Atredan countered, demonstrating a grasp of Wrigglie street insults, if not diplomacy. "Open it and let us in."

"'S'locked until sunrise. Come back at sunrise."

"We're here now, and we have affairs at the palace. The palace, do you hear that, pork-sucker? Open the damned gate."

The nameless guard and the cadet heir exchanged insults until Molin hissed, in Rankene, "Flatter him, for mercy's sake, or we'll be standing out here until the sun has indeed risen."

"Flatter him?" Atredan exploded, also in Rankene. "The man is stinking drunk! Flatter him yourself, Lord Torchholder. I don't stoop that low."

"Lord Torch?" the guard inquired. More of Sanctuary's swarthy natives understood Rankene than could--or would--speak it, and,anyway, names remained the same, regardless of language.

Molin stepped into the torchlight beside Atredan. "It is I," he confessed.

"Come with another army, eh?" The guard laughed heartily at his own joke. His breath was sour enough to light a fire at four paces.

Molin Torchholder had never intended to become heroically famous in Sanctuary. He had never intended to save the city from itself, either. But he'd done both when he'd led a hundred mounted Irrune warriors through a conveniently unlocked gate and put an end to the Dyareelan reign of religious terror. In gratitude, every unwashed survivor counted Molin Torchholder among his closest friends.

On occasion, gratitude could be useful. "No army, this time," Molin said with better Ilsigi pronunciation and grammar than the guard had used. "I've been out lighting bonfires at Land's End, and now I just want to sleep in my own bed."

"Bonfires, eh? You could've done your lighting right here, Lord Torch, never mind them folk at Land's End. Them Irrunes, they been lighting fires since they got here yesterday." The guard whistled through absent teeth. "Burggit's done pulled everyone in close, leavin' me here by my lonesome with orders not to budge the gate 'til sunup. 'Git's not taking chances the Dragon'll light something wrong. Only thing worse'n a loose fire is a dead Dragon, eh?" Once again, the guard rewarded his humor with aromatic laughter.

Crude as the analysis was, it was also correct. "Good man, you say you know who I am. If the Dragon's setting Sanctuary ablaze, I need to get to the palace. Unbar the gate for me and my companion."

"'Taint just the Dragon, Lord Torch. All them Irrune been setting fires, same as if they been riding Lord Serripines' tail. 'Git had the name for it, but it's passed clean from my ears."

Silently Molin berated himself for growing old and forgetful. The year he'd spent among the Irrune--the year before he'd led them to Sanctuary's gate--they'd heaped up huge mounds of straw and set them afire, saying their divine ancestor had entered the world through similar flames. Irrunaga's birthday was a movable feast. The bonfires Molin had watched had been lit beneath the firstfull moon after the autumn equinox, a full month before the Rankan Foundation festival--that year.

This year? Molin did the calculations. (Any priest worth his prayers knew the sky calendars as well as he knew the civil ones.) This year, the moon overhead this very night was the first full moon since autumn equinox had passed.

He begrudged the coincidence and the inconvenience, then, with a second thought, reconsidered the coincidence. The Irrune were as raw and rowdy a nation as ever galloped out of the eastern heartland. Their superstitions put Sanctuary's Wrigglie-speaking mongrels to shame, and their language was so primitive that they'd borrowed words left and right to describe their new homeland, yet they looked Rankan; and the Rankan myth said that before there'd been a Rankan Empire or even a Rankan kingdom, there had been a band of horse-riding warriors from the east.

If he'd been a full-blooded Rankan, Molin might have been appalled to think that the likes of Arizak and his kin were distant cousins, but he wasn't full-blooded anything except tired.

"Open the gate, good man," he pled with the guard. "Which are your barracks? I'll see that Burggit knows I'm the one who countered his orders."

The guard resisted. "Them Irrune--The streets ain't safe, Lord Torch, and you--pardon me--ain't no youngster to skip from trouble. No, no--trouble finds you, Lord Torch, and 's'my head will roll twice over for forgettin' my orders and for lettin' trouble find the Lord Torch."

"I have an escort." Molin indicated Atredan, who needed no encouragement to scowl and draw his sword.

The guard made one more protest, then relented. Moments later, to the clank of metal and the scrape of wood, the smaller of the two heavy doors cracked open. Atredan slipped through first. Molin followed.

"Don't forget," the guard called after them. "Tell Burggit 'twas on your orders, Lord Torch, that Leaner Vurben opened the gate. 'Tweren't no thought of Leaner Vurben's, 'twas your orders, Lord Torch." The clatter of the closing gate drowned out anything else Vurben might have said.

"Did you hear that? The brazen cur," Atredan complained."You're not thinking of running this Burggit to ground, are you? Let the man suffer."

"For what? I did countermand his orders. Common men expect protection from their officers."

"That man presumed to give you an order! He gave orders to an Imperial lord. He spoke to you as though you were another Wrigglie pud. He should be made an example of. Forget this Buggit; go to Captain Eraldus--he knows who puts food on his damn plate. He'll take care of that Vurben fellow."

Molin sighed quietly. He was a lord, and he enjoyed his privileges, but he wasn't an aristocrat. "I've found it useful, over the many long years of my life, to keep my word when I can. Oddly enough, if you honor the small things, the big ones are less significant. It took me years to learn that lesson."

"But a common Wrigglie pud! Who cares if you keep your word to him?"

Molin didn't bother to answer. When he'd given the orders to expand Sanctuary's walls, he'd imagined a plaza here between the old wall and the new--a place where visitors could be scrutinized from front and back, and cut down with impunity, when necessary. As with so many of his plans for Sanctuary, the final result bore little resemblance to his original vision. Instead of an empty plaza, there was the Tween, a relatively peaceful quarter populated largely by smugglers and hostlers.

The Tween's main street--such as it was--connected the new gate to the old gate, once called the Gate of Gold, but an empty arch these last fifteen years. Past the arch, the Wideway opened up between Sanctuary's wharves and its warehouses. Midway down the Wideway, the Processional branched north to the unbreached walls of the palace, which had hosted as many rulers as the great god Savankala had had mortal mistresses.

Both the Wideway and the Processional were lit by public lanterns--an Irrune innovation that spoke well of Nadalya, Arizak's second wife, who'd initiated it. There were torches, too, stowed in old barrels here in the Tween and at other intersections. It was said, though not in their hearing, that the Irrune feared the shadows and sounds of Sanctuary at night. Neither the torches nor the lanterns were necessary on a full-moon night, but, as Molin had learned,people took note of the small ways in which their rulers kept faith with them.

Molin took a stride in the Wideway direction. An unexpected shiver shook his spine, and he stopped. As a boy he'd been taught to equate such moments with his god's presence. The prayer of welcome and acceptance came reflexively to his tongue and waited for his mouth to open, but Molin swallowed instead. There was still a god bearing Vashanka's name and attributes somewhere, maybe within the Rankan Empire, maybe sulking somewhere in Sanctuary--immortals faded, but they never quite died. Molin Torchholder dutifully dedicated his rituals and daily prayers to his hidden god; but when a cold finger touched him, the erstwhile priest looked in a different direction.

The gods alone--all the Rankan gods, not just Vashanka--knew how Molin's life might have gone if his priestly teachers had guessed the nature of the talent he'd inherited from his temple-slave mother. Most likely, he'd have had no life at all. Indeed, Molin, in his role as a Rankan priest, would never have allowed himself to be born if he'd had the opportunity to take his mother's measure.

Of all the sorceries known to the world, witchcraft was the darkest, the most mysterious, and the one favored by the Empire's northern enemies. Officially, witchcraft did not exist in the Empire. There was prayer, which directly invoked divine power, and there was magic, which--according to priests, if not magicians--used spells for indirect invocations to the same gods. Witches, in the Rankan scheme, were witless mages who'd surrendered their souls to gods so foul and evil that mortal tongues could not pronounce their names.

Rankan priests, especially the warrior-priests of Vashanka's hierarchy, were adept at piercing a witch's deception. The fate of a witch in the bowels of a Rankan temple was necessarily bleak: interrogation by torture and punitive mutilation, followe

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...