- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

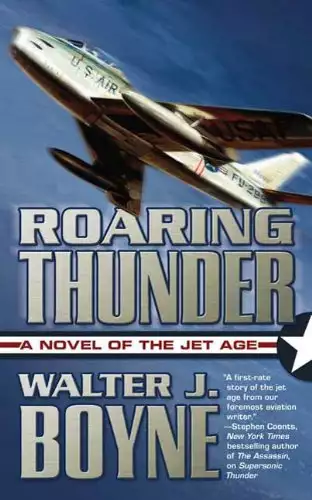

The story of the jet age of aviation revolves around remarkable geniuses--including Sir Frank Whittle, the British inventor of the jet engine; Hans von Ohain, a German jet engine designer who comes to work for the U.S.; famed aeronautical engineer Kelly Johnson; the daring test pilot Tex Johnston, and many more--brilliant men who conceived these early extraordinary airplanes and had the courage to fly them to new horizons.

Roaring Thunder blends real life adventures of the industry giants with the fictional Vance Shannon and his aviation family. Shannon, a prototypical American test pilot, sees and guides the birth of American jet aviation, while his sons, Tom and Harry fly the new jets in combat. Their aviation careers are blessed by their skill and courage, and they help usher in the greatest advance in aviation history with the birth of the jet transport. The Shannons serve as counterparts to the real-life heroes, creating continuity and explaining the intricacies, successes, and setbacks of a brand new industry.

The dramatic, totally accurate story of the beginning of the jet age is presented against a background of personalities, real and fictional who bring the story to life, and represent the first stage in the first ever fiction trilogy about the history of the aerospace industry.

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: April 1, 2007

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Roaring Thunder

Walter J. Boyne

August 27, 1939, Marienehe, Germany

The turgid waters of the Warnow River lapped at the stone-covered beach, the gentle gurgling muffled by the dense fog spreading its tendrils deep over the grassy flying field. A thousand yards away five men worked feverishly in the yellow light billowing from the "Special Project" hangar doors, checking the small, almost dainty aircraft they had just rolled out. Cautiously, as if they were handling a live bomb, they wrestled the plane into a 180-degree turn so that the odd circular hole at the end of the fuselage pointed out toward the river.

Fritz Obermyer sat on the edge of the Fiat Toppolino's tiny running board, his 120 kilograms of muscle and fat tipping the car, suppressing its springs, and sending the glow of its headlights at a cockeyed angle. Obermyer drew deeply on the stub of a cigarette, felt its warmth flare beneath his nose, then carefully dropped it beside him, grinding it into the tarmac with his foot.

He nudged his companion and pointed. "Look at him. When he came here three years ago, a little snot-nosed graduate student from Göttingen, I thought he was crazy."

Gerd Müller, short, lean, and wiry, stretched and laughed. "You tried to give him a hard time, Fritz, but he drove you crazy being polite. No matter what you said—or what you wrote on the wall in the latrine—he never lost his temper."

As Frontsoldaten, they were accustomed to discomfort and waiting, and the long hours spent at the field meant nothing to them. Obermyer had left the Berlin Institute of Technology to volunteer for the army in August 1914. Now he was nominally a machinist foreman in the new plant building the Heinkel He 111 bomber. A forceful personality, he had used an artful combination of his engineering training and his Nazi Party connections to become accepted as an aide to Ernst Heinkel himself. Heinkel was at first quite resistant to the idea but over time, as Obermyer's talents became obvious, welcomed his assistance.

Heinkel found that he could depend upon Obermyer to know what was happening on the factory floor, in the long rows of drafting tables, and in the local Nazi Party headquarters, usually long before anyone else was aware of it. The information was often invaluable, and within a few months of his employment, Heinkel looked upon Obermyer as an indispensable political divining rod. Müller was an excellent machinist but had been attached to Obermyer—at his insistence—as an assistant.

The arrangement suited the plant management, who saw Obermyer and Müller as agitators. They were glad to have them off the factory floor and worried each time Obermyer came through, acting as if he were the local feudal lord, gathering information and dispensing favors. They, like Heinkel, knew better than to protest. The firm was already at odds with the government, and everyone wanted to avoid any further difficulties with the Nazi Party. When Obermyer suggested that he be attached to the Special Project organization, Heinkel acquiesced—the more sensitive a project was, the more hazardous it was to raise a political issue.

Obermyer could intimidate most people with a glance; stone-cold gray eyes gleamed from his cruelly scarred face, and he walked as he had for four years in the trenches, bent over, moving with a menacing hunched step that made it seem as if he was about to leap on his prey. Yet he was also an able humorist, able to prick egos with the little two-line poems he wrote on the mirrors of the noisome latrines of the Heinkel Aircraft Works factory. He wasn't always malicious but was usually apt, and the workers waited as eagerly for his latest poem as some of them might wait for the latest joke on the Nazi Party. He wrote those occasionally, too, just to see who laughed and to make a note of it. He wielded his party membership just as he had used his role as a quartermaster sergeant in the Roehlk Freikorps after the war—to his own advantage. And while most Nazis bragged about their low party membership numbers, confirming their early support for Hitler, Obermyer's reputation was built on the decisive action he had taken in 1934 during the "Night of the Long Knives" when Adolf Hitler had squelched a Brownshirt revolution and executed Ernst Roehm. When one of Roehm's none-too-alert bodyguards had attempted to sound the alarm, Obermyer had cut him down with a single slash of his favorite brawling tool, a razor-sharp trench shovel. From that night on he was an icon in the party, a symbol of action and loyalty to the Führer. But far from being a convinced Nazi, Obermyer was an opportunist, pure and simple, intent on looking out for his own interests at all times.

Müller was an old comrade, a companion in adversity in the trenches, where they had not only saved each other's lives but, more important, saved each other's sanity as well. No matter how desperate things became, no matter how short on food or how bad the morale, they each had the other to rely upon. They were inseparable, with Müller content to follow where Obermyer led, ready always to do what he said. Müller had once made a joking threat to some of the Heinkel workers, saying, "Obermyer is the brains and I'm the muscle." Obermyer heard him and interjected, "I'm the brains and he's the stomach." Both men were correct.

In July 1918, Müller had watched Obermyer save another life, that of a twenty-year-old new recruit in a sappers' battalion. They were in a just conquered French village behind the line of German advance. The young soldier was engaged in loading mortar shells from an abandoned truck into a horse-drawn sled when Obermyer had grabbed him by the neck and tossed him into a shell hole and fallen on him. In the next instant four 105mm artillery shells landed, one detonating the mortar shells and blowing the truck, horse, and sled to atoms.

The old soldier in Obermyer had heard the inbound whistle, judged the accuracy of the artillery, and acted accordingly. The young recruit, Willy Messerschmitt, was profoundly grateful.

By 1937, Obermyer had worked for Heinkel for three years when he contrived a meeting with Messerschmitt, a rising star in German aviation. Obermyer reminded him of their first meeting, suggesting that Messerschmitt might like to have a man inside the Heinkel plant to "keep an eye on things." As grateful as Messerschmitt was to Obermyer for saving his life, he was repelled by the suggestion.

Yet things were difficult for him. The State Secretary for Air, Erhard Milch, hated him, for he had lost a close friend when one of Messerschmitt's Me 20 early passenger transports had crashed because of a manufacturing defect. The feud continued over the years and Milch had repeatedly denied him contracts. At the time of their meeting, Heinkel and Messerschmitt were engaged in a bitter competition to build the Luftwaffe's next fighter, and, given Milch's attitude toward him, Messerschmitt knew that he needed all the help he could get. They made a verbal agreement, never yet breached, that Obermyer would supply important inside information on Heinkel projects directly to Messerschmitt himself, in return for a sizable monthly cash stipend. So far it had worked well, particularly in the fighter competition. Messerschmitt valued Obermyer's carefully collected estimates on the man-hours required to build the Heinkel 112, for these were far higher than Messerschmitt's Bf 109 required. Messerschmitt used the figures with devastating results in his proposal and believed that they had done much to win the competition for him, even though his aircraft was both faster and more maneuverable.

Obermyer had long since found that being disliked in a position of relative power had its advantages. No one ever objected when he proposed that he attend a conference, even those held in other European countries—they were glad to have him away from the factory. Because of his background, he preferred engineering conferences, although an international air show was almost as satisfactory. Two or three times a year, depending upon the business climate, he would travel to conferences where he met representatives of companies in other countries. Almost invariably, he would find among them someone who was willing to pay for information. His latest contact was the firm of Marcel Bloch, which built handsome fighters for France and needed information on the gear retraction system Heinkel had used in the high-speed He 70 "Blitz." He preferred to be paid in English sterling but would accept good information in exchange, as long as he believed he could sell it elsewhere.

Now Müller and Obermyer watched as the twenty-seven-year-old physics specialist von Ohain bounded around the little He 178, peering like a mother hen over the shoulders of the men preparing it for flight. Coatless, Dr. Pabst Hans von Ohain was oblivious to the cold, totally absorbed in the last-minute adjustments to the engine he had created from his imagination and three years of hard work. He had seen his dream move from his ideal of a noiseless, part-less engine to a ferocious whirling combination of heat, sound, and thrust, more than four hundred kilograms of it.

Von Ohain moved like a shadow to Max Hahn, the brilliant mechanic who transformed von Ohain's ideas into the complex assembly of sheet metal and steel castings that formed the primitive jet engine, more than seven meters long, nestling inside the aircraft's fuselage.

"He took my joking well." Obermyer looked at von Ohain's tall, slender figure with approval. "If Warsitz can keep from crashing this crate, young Hans will be a rich man someday."

Müller picked up a stick and began knocking mud from his boots. He and most of the Special Project team had spent the two previous days tramping up and down the field, tamping down high spots and filling in shallow depressions, to make sure there were no problems on takeoff.

"Better save that stick for the birds, Gerd." Obermyer snorted. Yesterday, on an early-morning taxi test, the jet engine had sucked a seagull into the intake, forcing an immediate shutdown. They had to push the airplane all the way back to the hangar, disassemble the engine, pluck out the bits of raw and cooked seagull, then put the engine back together. There was no apparent damage, but it added to the morning's uncertainty and to the intensity of the inspection.

Everything had to be ready for the big moment when Professor Ernst Heinkel himself arrived in his custom-bodied Mercedes. Short, dark, his face dominated by an oversize nose that seemed to overflow his spectacles, Heinkel had been a prime mover in German aviation since the 1914–18 war, designing and building many of the most important aircraft used by the German and Austro-Hungarian air forces. In 1933, he'd been persuaded to build a new factory for three thousand employees in Rostock. Now it employed five times that number and was overflowing into the Marienehe suburb, turning out dozens of twin-engine He 111 bombers every month. The main factory buildings, beautifully aligned, gleaming with acres of windows, were a stark contrast to the ramshackle secret hangar housing von Ohain's creation.

Heinkel was a canny businessman. Recognizing that he was of the wood, wire, and fabric era, he hired the best people he could find as he pushed forward with sleek, all-metal aircraft. He was ambitious and longed to expand his interests to include an engine factory, as Hugo Junkers had done. There was no chance that the Air Ministry would give Heinkel the license and the materials to enter the piston engine market, but this new jet engine of von Ohain's was a different matter. The deferential young physicist, so polite that he seemed more like a choirboy than a genius, had convinced him that turbine-jet engines could be built that would outperform piston engines. More important, von Ohain had convinced him that they could be built more cheaply, using relatively inexpensive conventional equipment, and could be developed far more quickly. This morning would prove whether von Ohain was right or not.

At the edge of the tiny field, Müller shivered. It was cold for late August, and all of them had been there since three o'clock. "Is the movie-star test pilot here yet?"

"No, he's probably kissing some pretty little secretary good-bye. He lives a pretty hectic life." As they spoke, a black Horch drove up and the test pilot, Erich Warsitz, popped out. Even though he was six feet tall, blond, handsome, and talented, Warsitz was still popular with the rough-hewn factory crew because he was so matter-of-fact about risking his life testing the most advanced—and implicitly dangerous—Heinkel planes.

Müller fumbled in his pocket, producing a knife and a sausage wrapped in paper. He sliced two thick pieces of sausage, handed one to Obermyer at the point of his knife, and held the other in his hand; it was a familiar gesture, first practiced twenty years ago, when they were starving teenage soldiers together. Müller had sworn never to go hungry again and ate as much as he could whenever he could, never gaining an ounce of weight.

"I don't blame him—a short life but a merry one. He damn near killed himself just last June, flying the rocket plane. He takes too many chances."

They watched as Warsitz, swinging a good-sized hammer by its handle, joined the group at the hangar.

"Good morning, Dr. von Ohain; are we going to fly this morning?"

"Yes, Herr Warsitz, as soon as Professor Heinkel arrives—and the fog lifts. First, we are going to test run the engine." Smiling, he pointed at the hammer, saying, "I see you have your patented escape equipment in hand."

Warsitz nodded uneasily. He still was not entirely accustomed to aircraft with canopies, preferring open cockpit planes, where if you had trouble you could go over the side in an instant. The hammer was for breaking his way through the canopy if it jammed. Despite his cool test pilot demeanor, he was well aware of the danger. Earlier in the month he had made a short series of taxi tests and actually "hopped" the experimental jet plane off the short runway for brief, straight-ahead flights. He was convinced that the He 178 was the door to the future—but he knew it could easily be his coffin as well, for it embodied so many untested ideas.

Normally companies tested new airframes and new engines separately. They would fly a new engine in an old design to test it or fly an established engine in a new airframe for the same reasons. But the He 178 was a new airplane and a new engine—and that was doubly dangerous. That morning, for the first time in his test-flying career, Warsitz had left behind a letter to be forwarded to his parents if anything had happened. More telling, he had made a special good-bye to his beloved dachshund, Max.

"I'd like to do some more taxi tests before we fly—I'm still not satisfied with the brakes."

"Of course. We'll do a quick test run, then turn it over to you."

Warsitz and von Ohain companionably walked around the aircraft, looking at it with two widely divergent views. To von Ohain the airplane was just a vessel for his engine, no more important than a packing box. To Warsitz it was, like all airplanes, a thing of beauty that must be courted and also feared. He drew tactile pleasure from running his hand over the surface of the airplane, enjoying its aesthetics, letting its curves speak to him. The plane was simple, with smooth lines, totally functional, exactly what he liked in a design. He dropped down and squatted, letting his eyes look over the entire aircraft, seeking leaking fluids, incipient cracks, loose nuts and bolts, or any other untoward signs that might compromise safety.

"I understand that the bird did not damage the engine?"

"No. We disassembled it, balanced all the parts, and checked for cracks. The only thing we had to do was clean it."

Von Ohain glanced closely at Warsitz's face and went on somewhat anxiously, "It might have been worse in a conventional plane; the bird would have broken a wooden propeller, and perhaps even damaged a metal one."

Warsitz nodded and smiled, patting von Ohain on the back, knowing how proud he was of his engine. "Well, shall we get started?"

Von Ohain nodded to Hahn, and they brought a cylinder of compressed hydrogen over to start the engine. From a distance, Obermyer saw the group scatter, leaving only von Ohain and Hahn at the aircraft. Even as he moved away to stand behind the Fiat he said, "They're scared of the hydrogen. Ever since the Hindenburg, everyone expects hydrogen to blow up. It's no more dangerous than acetylene or gasoline, if you know how to handle it."

Hahn could have tested the engine up by himself, but von Ohain stayed with him for moral support. Von Ohain's desire for privacy to think out his engineering problems had evolved an unusual method of dealing with people. Rather than being withdrawn or abstracted, he related to each person as closely as possible on their terms, trying to establish contact on their ground, and by extension removing them from his. He treated everyone with the same consideration and courtesy, whether it was the guard at the gate or Dr. Heinkel himself.

To von Ohain, every run of his engine was as dangerous as the headlong plunges he had taken while skiing in the Harz Mountains and the hydrogen priming was the least of it. Over the course of his three years of testing, he learned that jet engines could explode in many ways, rarely with any warning. The temperatures and the turbine speeds were so high so that anything could go wrong, from an explosion when the gasoline was injected to the turbine blades flying loose. But when it ran sweetly, it was a joy, a smooth, quiet roar of power that von Ohain knew was the sound of a new era in aviation, one he had brought about in just three years with a small team of experts and a few hundred thousand marks of Ernst Heinkel's money.

Hahn was in the cockpit, gently pushing the throttle forward, then retarding it, the Heinkel He S 3 jet engine docilely responding, the spurt of flame and the noise rising and falling in concert. Von Ohain nodded, and Hahn shut the engine down.

"Let's inspect it once more, then let Herr Warsitz do his taxi tests before the Professor arrives."

The early-morning sun sent its welcome warmth from the dark blue sky, slowly dissipating the fog from the hard-surfaced areas of the field first.

Warsitz shoehorned his lanky body into the tiny cockpit and methodically went through the standard control checks before signaling to von Ohain that he was ready for the engine start. The cockpit was stark, with fewer than a third of the instruments of the Heinkel 112 fighter he had flown the day before. They did not need many instruments—all he had to do was get the aircraft airborne, fly it around, and land; that would be enough to prove that the jet engine worked.

Obermyer watched from the sidelines as Warsitz allowed the jet to run forward for one hundred meters. It slowed abruptly and then began drifting to the left, threatening to collapse the gear and end the test—and perhaps the entire jet engine experiment—on the spot. The ground crew was already running toward the airplane when Warsitz regained control and taxied back to the hangar, his concerned expression saying it all.

Hahn and three mechanics swarmed over the He 178, and Warsitz tried it again just as Heinkel's big Mercedes limousine pulled in. The taxi test was satisfactory this time, and Warsitz stayed in the cockpit as the aircraft was refueled. More agile than he looked, Heinkel climbed up the ladder next to the cockpit to shake Warsitz's hand and give him the traditional "break a leg" good-luck wish.

The flight meant much to Heinkel. With the exception of a very few important people such as Ernst Udet, Heinkel was persona non grata with the Nazi Party, in part because he looked so much like the Nazi cartoon stereotypes of Jewish plutocrats, in part because he had fought so hard to retain Jewish workers, particularly engineers, while the government insisted that they be purged. If Warsitz demonstrated that the jet engine actually worked, that this simple, inexpensive power plant could propel a plane through the air, Heinkel could get the backing to buy a factory to manufacture them, and he would build Heinkel aircraft powered by Heinkel engines. If it failed, he was once again at the mercy of the idiots at the Air Ministry, men so foolish that they demanded every bomber, no matter how big, be a dive-bomber.

Von Ohain and Hahn walked cautiously around the airplane for perhaps the twentieth time that day, peering into the air intake, popping open a few panels and inspecting inside, then carefully feeling along the bottom of the aircraft to be sure that no fuel was leaking.

With an impatient nod, Warsitz signaled to start the engine. There was a momentary hesitation, then a sudden blowtorch roar as the engine caught on and advanced to idle speed. Warsitz checked the engine temperature gauge, the fuel pressure, the oil pressure, and finally, satisfied with the readings, waved to von Ohain and motioned for the chocks to be pulled from in front of the wheels.

Warsitz was apprehensive. He had a sense of the plane from the taxi-test hops, but this would be the first real flight in a brand-new airplane, unlike any that he had ever flown before. His big hands held the stick back in his lap and moved the throttle full forward. The tiny jet moved, slowly at first, then more swiftly, and he relaxed back pressure, allowing the tail to come up. Without a propeller, there was none of the customary torque that was so dangerous in piston-engine-powered fighters, and the little He 178 moved over the grass, straight as a die. The noise of the jet was subdued compared to that of the aircraft with powerful piston engines Warsitz had flown recently, so quiet that he wondered if it was producing the necessary power. He passed the tiny white flag that marked the 100-meter point, then felt the plane begin to come alive, moving more lightly on its gear, accelerating as it passed the 200-meter mark, the noise of the engine seeming to decrease, and then, almost instantaneously, at the 300-meter mark the airplane broke ground, transforming into a silent missile being sling-shot upward, hurtling toward the temporary redline speed of 600 kilometers per hour. He tried to raise the landing gear, but nothing happened.

On the ground, von Ohain had stood transfixed as the tiny monoplane rumbled forward, barely accelerating, so that it seemed to take forever before Warsitz pulled it from the ground. A cheer went up as Warsitz climbed steeply to 2,000 feet. Von Ohain whirled to glare at the crowd—the flight would not be a success until Warsitz was back safely on the ground.

Inside the cockpit, perspiring heavily now, Warsitz slowed down and tried again to retract the landing gear, which was operated by compressed air. When the attempt failed, he decided to leave the gear down and land after only one circuit of the airfield. The airplane was nose-heavy, and Warsitz had to maintain back pressure on the stick when he throttled back to hold 600 kilometers per hour on the airspeed indicator, keeping the field in sight, wanting now only to get the airplane down safely to the ground. He turned to the final approach, reduced power, and kept feeding in back pressure until the wheels touched down at the very edge of the field with a gentle thump. He bounced once, recovered, then rolled out smoothly, pushing the canopy back before taxiing in.

Von Ohain joined in the cheering as Heinkel grabbed him by the shoulder, screaming, "Congratulations, Dr. von Ohain. This is the world's first flight in a turbine-powered aircraft! I'm going to make you a very rich man!"

The nose of the little silver He 178 bobbed up and down as it taxied across the rough grass field, to be met by Heinkel and von Ohain leading the entire Special Project team and a pack of excited engineers and maintenance workers.

Warsitz lifted himself out of the cockpit, shook hands with Heinkel and von Ohain, and said just, "Nose-heavy," to Hahn. The fuel was topped off as Hahn and the team of Heinkel mechanics adjusted the stabilizer. Warsitz carefully checked the landing gear system—there was no apparent anomaly, but he decided to have a down lock installed and just leave the gear extended on the next flights.

Calmer now, Warsitz took off again. The trim was now satisfactory and the little airplane flew almost hands off, requiring just a caress on the controls to keep it flying straight and level. He made a half-dozen passes around the field before coming in to refuel.

He talked excitedly to von Ohain and Heinkel, finally persuading them to let him make one last flight, longer than the others, to get a better check on fuel consumption. The takeoff was uneventful and he flew straight to Warenemunde on the Baltic Sea, a fifty-mile flight that he knew ran the little plane close to its range limits.

As his apprehensions subsided, Warsitz felt a growing elation in flying the strangely quiet aircraft, so different from the noisy racket of a conventional fighter. Looking at the altimeter, he realized it was stuck, not moving. He tapped it and it leaped to indicate five hundred meters.

"Ah, no vibration. So quiet the instruments stick!" Recalling the pre-flight briefing, he kept the airspeed just under 600 kilometers per hour. The controls were featherlight, and he rocked the wings back and forth, contemplating rolling the airplane but knowing better than to risk such a move on the first test flight. By now he was comfortable enough to take his eyes off the instrument panel and look out to his right over the whitecapped Baltic to see the local fishing fleet moving toward its station, and then back left to the town of Warnemunde. Defiant, Warsitz flew low over the Arado aircraft plant, in a gross violation of Heinkel's passion for secrecy. Warsitz knew the test pilots there and wanted to give them something to talk about.

Warsitz then banked back toward Marinehe, where von Ohain and Heinkel, acutely aware of the aircraft's limited range, were already feeling a sudden surge of fear that things had gone too well and that trouble was brewing.

Their fears were drowned in the excited buzz that grew as the little jet whistled in from the north, then soared again when they realized Warsitz was too high to land without making another circuit.

Inside the cockpit, sweating profusely again, the test pilot pressed his head against the canopy to keep the field in sight. As he positioned himself to make one high pass over the field, then come in and land, the engine cut out briefly before resuming its song of power. Knowing he was short on fuel and confident in his mastery of the aircraft, Warsitz did not hesitate, side-slipping the new plane to shed altitude swiftly. Heinkel and von Ohain gasped and started forward, their hearts pumping, as the little monoplane slipped steeply earthward, to recover just at the edge of the field, touching down smoothly and rolling in to the jubilant waiting crowd. It was masterly, heart-wrenching flying—few others could have pulled it off.

Heinkel, tears streaming down his face, turned and embraced von Ohain, saying, "You have just given birth to the jet age."

Obermyer and Müller pulled away from the crowd. They had helped set up the celebratory feast that was to follow. There would be plenty of champagne (minus, of course, the case Obermyer had slipped into the back of his car) and both men intended to arrive early.

"Well, Fritz, as you said, von Ohain will probably become a rich man from this. And Heinkel, too."

"They will not be the only ones, Gerd. I believe I can think of ways that will let us profit as well."

"It didn't look like much to me. Just whoosh, up and down—no guns, no bombs, nothing."

"Gerd, let me tell you something. Sometimes an avalanche starts with a single rolling snowball. We just saw the snowball."

Copyright © 2006 by Walter J. Boyne

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...