- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

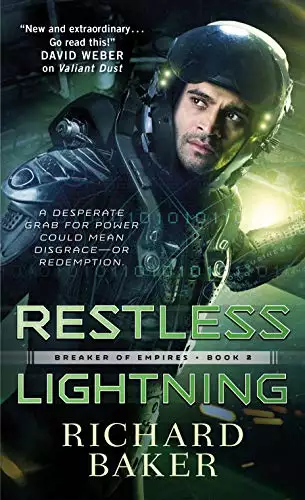

Richard Baker continues the adventures of Sikander North in Restless Lightning, the second audiobook in his new military science fiction series, Breaker of Empires, and sequel to Valiant Dust.

Lieutenant Sikander North has avoided an outright court martial and finds himself assigned to a remote outpost in the crumbling, alien Tzoru Empire—where the navy sends troublemakers to be forgotten. When Sikander finds himself in the middle of an alien uprising, he, once again, must do the impossible: smuggle an alien ambassador off-world, break a siege, and fight the irrational prejudice of his superior officers. The odds are against his success, and his choices could mean disgrace—or redemption.

Release date: October 23, 2018

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Restless Lightning

Richard Baker

Bagal-Dindir, Tamabuqq Prime

“This is a damned peculiar way to travel,” remarked Commodore William Abernathy in a sour tone. He waved one hand to indicate the open-sided carriage in which they rode, the elaborately dressed Tzoru driver with his—or her?—painted dermal patterns, and the alliksisu yoked to the boatlike prow. The Aquilan flag officer fidgeted in a vain effort to find a comfortable posture for his seat. Short and slight of frame, with iron-gray hair and a stiff terrier’s mustache, Abernathy disliked sitting still, especially on a cold and damp day. “It’ll take us half an hour to reach the embassy at this pace, and I’ll be damned if it isn’t snowing by the time we get there.”

Lieutenant Commander Sikander Singh North, Commonwealth Navy, noted that his new commanding officer’s favorite word appeared to be “damned” and carefully hid a smile. He found the cold, clammy weather uncomfortable too, but he had about thirty kilos on Abernathy, all of it muscle. Most people from his homeworld—Jaipur, in the Kashmir system—possessed the stocky, broad-shouldered frames common among natives of planets a little over standard gravity. If he felt the chill through his Navy overcoat, the commodore probably felt like he was sitting in a freezer.

“It’s tradition, sir,” he told the commodore. “At least the ride is smooth.” Maglev rails buried under the avenue powered every street in the Tzoru capital, providing a wheelless suspension for the carriage. The transportation network had been installed around the same time ancient humans had first figured out agriculture. Time and again during Sikander’s tour of duty in the squadron posted on the Navy’s Helix Station he’d started to believe he might actually understand something about the culture or psychology of the alien Tzoru—and time and again he’d been confronted by some new piece of evidence that humans didn’t really understand the Tzoru at all. For example, powering the roads but not the vehicles. Leave it to the Tzoru to come up with that one!

“Tradition? A damned stupid one, I suppose,” Abernathy muttered, confirming Sikander’s suspicion about his favorite word.

“Powered ground cars would challenge the place held by the carriage-driver sebetu, sir,” Captain Francine Reyes explained to Abernathy. Tall and poised in comparison to her wiry, energetic superior, she wore a more or less permanent frown of disapproval at the various idiosyncrasies of the Tzoru. Abernathy had taken command of the squadron patrolling Helix Station only a week ago, but she’d served as deputy commodore under his predecessor for more than a year. Like Sikander, she’d had plenty of time to experience the peculiarities of Tzoru customs.

“Sebetu—those are the Tzoru clans, right?”

“Something about halfway between a clan, a guild, and a caste, yes.” Reyes had anticipated that the weather might be cold; she at least had dressed warmly for the carriage ride. She continued her explanation: “Taking away the role of the carriage-driver sebetu would upset the harmony of things. The Tzoru simply don’t do that unless they must.”

“Are you serious, D-Com?” said Abernathy. “In ten thousand years no one’s convinced the taxi drivers to retire their ridiculous draft beasts? So why couldn’t we just land at the embassy grounds and skip the whole thing?”

Sikander took that as his cue. “Sir, no one flies over Bagal-Dindir except for members of the aristocratic sebetu or their soldiers. If it’s any consolation, the privilege of an official carriage is a sign of Tzoru deference to your rank. Otherwise we’d have to take the trolley or walk.” He’d learned more than a few hard lessons about Tzoru inflexibility during nineteen months as Helix Squadron’s intelligence officer, especially when it came to Tzoru military protocols. Sikander was a line officer by trade, but not even a career intelligence specialist could be expected to make sense of the contradictions and challenges every Commonwealth officer who rotated through Helix Squadron encountered. In fact, the Admiralty staggered relief assignments specifically to ensure that the squadron staff always included at least a few officers who’d been on Helix Station for some time.

“Walking might be warmer,” Abernathy said with a snort. He shivered inside his overcoat, and leaned forward to address the driver. “You, there. Can we go a little faster? I want to beat the snowstorm.” The translation device clipped to his collar emitted a string of guttural Tzoqabu a moment after he finished.

The driver turned to regard the small party reclining in the open carriage, twisting easily in a motion that would have tested a human contortionist. He (or so Sikander guessed, since humans could have a difficult time telling Tzoru of different sexes apart) replied to Abernathy in Tzoqabu; Sikander’s own translation device fed the interpretation into his ears: “The alliksisu has no interest in hurrying, honored friends, but if you are cold I can activate the heating plates.”

“There is a heater?” Abernathy asked in a flat tone.

“Yes, honored friend. I shall activate it.” The Tzoru adjusted controls on a small panel near his left hand, then returned to the task of directing the alliksisu—a creature that looked like a blue, scaly rhinoceros with long legs and three wide toes on each foot. A moment later, a pleasant warmth enveloped Sikander’s legs and began to well upward from the floor.

“Could’ve used that ten minutes ago,” said Lieutenant Mason Barnes, leaving his translator off. The fourth in Abernathy’s small party, Barnes—Sikander’s roommate in their Academy days, and one of the closest friends he had in the Navy—served as Helix Squadron’s communications officer. He had the pale complexion, red hair, and rural accent of a Hibernian. People who evinced characteristics of the old Terran races were somewhat unusual in the metropolitan worlds of the Aquilan Commonwealth, or any of the other great powers in the Coalition of Humanity. Noticeably distinct traits like the fair skin of the Hibernians, or the coppery complexion and wavy black hair common in Kashmir, indicated descent from populations that had been isolated at some point or other during humanity’s expansion to the stars. Mason caught Sikander’s eye and nodded at the driver’s back as if to say, A Tzoru being Tzoru, what can you do?

Sikander answered with a small shrug. Humans had encountered only four other starfaring species and the long-dead ruins of a few others in nine centuries of interstellar travel. Of the living four species, Tzoru were perhaps the most humanlike, but despite bipedal morphology and technology comparable to human technology, Tzoru were indeed alien. They had evolved from semiaquatic pack hunters millions of years ago; a sort of stiff cartilage made up their skeletons, and they had tough rubbery crests with breathing apertures instead of noses. In place of skin, Tzoru had a gray, leathery dermis with patterns of scales—broad and thick on the back and shoulders, finer and more colorful around the face. Their eyes were large and dark and set almost on the sides of their bullet-shaped heads, and their wide, lipless mouths were filled with serrated teeth. Tzoru dressed themselves in kilts and sleeveless tunics for everyday wear, layered robes in cold weather, or elaborately ornate robes when they wished to demonstrate their social status … which was at every opportunity, in Sikander’s experience.

Tzoru thought processes and emotions likewise ranged from near-human to coldly pragmatic and uncompassionate. They had nothing like the human drives of romantic love, ambition, restlessness, or a craving for thrills, but they showed great affection for friends and relatives. And they had exactly zero empathy for strangers, which meant that a carriage driver bundled up against the chill of a cold day would never even begin to imagine that his passengers might be cold if they didn’t bring it to his attention.

“I knew it. Now it’s snowing,” Abernathy observed. Sikander glanced up; sure enough, wet, heavy flakes drifted down from the gray clouds overhead. The commodore drew his overcoat more snugly over his chest and settled back in his seat with a sigh of resignation.

“If you’ll look over thataway, sir, you can see the Anshar’s Palace,” Mason said, perhaps hoping to distract Abernathy’s attention from the cold, wet ride. “Just through that gap in the treeferns, there. Those’re the monuments of the Royal Ward.” Slender spires, mighty domes, and steep-sided ziggurats loomed a kilometer or two from the boulevard down which they rode. Bagal-Dindir had the population of any large human city, but Tzoru built few high-rise buildings; as a result the capital sprawled over a vast area. In some neighborhoods one could hardly tell that one was in a city at all, but the Thousand Worlds ward—the city’s “Embassy Row”—stood in an old temple district not far from the seat of the Dominion’s government. The drive from the spaceport to the Aquilan embassy offered some of the better views to be found in the city.

“That big ziggurat with all the gold on it?” Abernathy asked, craning for a better look.

“Yes, sir. They say that one building covers almost three square kilometers.”

“Impressive,” Abernathy admitted. “Have any of you been there?”

“No, sir,” said Sikander. “Only a handful of humans have ever set foot in the palace.”

Reyes gave a small snort of disgust. “The Anshar’s attendants almost never permit non-Tzoru to sully the grounds with our presence. It’s rather insulting, if you ask me.”

“Hmmph.” Abernathy grunted and looked away, turning his attention to their immediate surroundings. Private homes, workshops, and small businesses dotted both sides of the boulevard, interspersed with open spaces that allowed longer views. Tzoru dressed in the colors of many different sebetu hurried from one establishment to another or rode along in carriages and carts that cluttered the street. Quite terran in many ways, Tamabuqq Prime had breathable air, oceans filled with water, natural flora dominated by green plants, and more or less Earthlike seasons and weather. But even after a year and a half stationed in the heart of the Tzoru Dominion, Sikander still found it disconcertingly alien. The sounds and smells were all wrong: the avians hissed and clicked instead of singing, overpowering spice-like scents filled the air, and the sky on a sunny day was a pale green hue.

Five more months, Sikander told himself. His tour in Helix Squadron would soon be over. The Tzoru frontier lay more than a month from Aquila’s core systems; it was the sort of place where ambitious officers went to make names for themselves without the oversight of their superiors, and superiors who didn’t want to deal with troublesome subordinates could send them out of sight and out of mind. Sikander belonged to the latter group: Very few Kashmiris served in the Aquilan navy, fewer still came from families as pedigreed or powerful as the Norths of Jaipur, and exactly one had taken command of an Aquilan warship in the middle of a battle, fighting through to victory in the face of orders to withdraw. After the prominent role Sikander had played in the Gadira incident, half the Admiralty had wanted to commend him, and the other half had wanted to court-martial him. The compromise that had eventually won out was evidently to hide him in the most remote post they could think of. But which side of the debate does Abernathy favor? The new commodore hadn’t bothered to tell Sikander whether he approved or disapproved of his actions at Gadira.

A snowflake slipped past the visor of his cap, narrowly missing his eye. Sikander brushed at his face, noting that the flurry seemed to be growing heavier. He hadn’t seen snow in years, a simple accident of assignments to bases in temperate climes and periods of leave that never seemed to align with the cold season at home. Now that he thought of it, it had been snowing the first time he met William Abernathy. Fourteen years ago, back at the Academy, a day filled with heavy flurries—

* * *

—dancing outside the high windows of Powell Hall’s formal hearing room. The afternoon is cold and gray; the furnishings are dark, old wood, massive as battlements. Sikander, a freshman, faces the Disciplinary Committee: five senior midshipmen with faces that might have been carved from stone. A dozen of Sikander’s classmates and upperclassmen from his company sit behind him; he can’t see them, but their silence is a tangible weight at his back. At the side of the room, Commander Abernathy, staff advisor to the committee, sits with his head leaning on his hand, watching the scene. His posture suggests he is falling asleep.

The committee chairperson, a senior named Adelaide Wallace, reads from a document: “Midshipman Fourth Class North, you have been placed on report for the infraction of striking a superior officer. Your company commander states that on the evening of February tenth, he found you engaged in a fistfight with Midshipman Second Class Gray. During this altercation he saw you throw several punches at Mr. Gray, and that you continued to do so even after you were ordered to stop. The purpose of this proceeding is to examine the facts of the report, provide you an opportunity to make answer, and then determine the appropriate punishment. This is an administrative proceeding and is not a hearing under the military justice code, but any statements you make here are considered to be in the public record and you are expected to be truthful under the Academy honor code. Do you understand?”

“I do, ma’am,” Sikander answers.

“Midshipman Second Class Gray and your company commander have already stated that they agree with the facts as stated in the report. Do you dispute any part of the report?”

Sikander hesitates before he speaks. “No, ma’am. The report is correct.”

Midshipman Wallace looks up at that. “You are admitting that you are guilty of striking Mr. Gray? The customary punishment is expulsion, Mr. North.”

“Ma’am, Midshipman-Commander Farrell accurately reported what he observed when he arrived on the scene and what Mr. Gray said to him at that time. But the report says nothing about what happened before Mr. Farrell got there, or whether Mr. Gray was telling the truth.”

“You dare to call me a liar, Snottie?” an angry voice snarls behind Sikander. A clatter of scraping chairs follows.

Sikander can’t help it; he turns around. Midshipman Victor Gray, a junior in Sikander’s own company, knocks his chair over as he springs to his feet. He is a tall, sandy-haired young man, stocky and strong for an Aquilan, and his face is twisted in fury.

Sikander looks him right in the eye. “Yes, sir. I do.”

Gray takes a half step toward him and balls his fists. The midshipmen that make up the Disciplinary Committee look at each other in confusion. Several people start to speak at once. But Commander Abernathy sits up straight and slaps his open hand on the tabletop in front of him so loudly everybody in the room jumps. “Strike that from the record!” he snaps. “And Gray’s remark too. We will have no such insinuations on the transcript, is that clear?”

Adelaide Wallace stares at Abernathy in surprise before nodding to the underclassman who serves as the committee clerk. “As Mr. Abernathy requests,” she says to him. “Strike the last two remarks, please.”

“Ms. Wallace, I suggest a brief recess,” Abernathy continues. Without waiting for her reply, he stands and marches over to where Sikander stands. He’s easily ten centimeters shorter than Sikander or any of the other midshipmen, but in that moment the only commissioned officer in the room seems to tower over everyone. It’s all Sikander can do to stand his ground without flinching. “North, come with me. I need a word with you.”

He spins on his heel and strides away as the midshipmen watch. Sikander stares after him for a moment, then hurries after him—

* * *

“What’s going on here?” Abernathy asked suddenly, rousing Sikander from the old memories. The commodore had a little more gray in his hair and gold braid on his uniform than the officer Sikander remembered from his Academy days, but seemed otherwise unmarked by the passage of fourteen years.

Sikander turned to see what had caught the commodore’s attention. Scores of agitated Tzoru crowded together in front of an open-sided shelter or hall a short distance up the street. Many wore green, double-pointed caps of a design he hadn’t seen before, and one individual standing on a parked cart led a responsive chant. At each pause, the Tzoru in the crowd raised their hands in the air and shouted wildly in response: “Ebneghirz! Ebneghirz!”

“Some kind of religious procession,” said Deputy Commodore Reyes with a scowl of disapproval. Like many Aquilans, Reyes had no use for religious beliefs of any sort, human or alien. “There’s some such nonsense every day in Bagal-Dindir. That building behind the crowd is a shrine—they’re all over the capital.”

“They seem worked up about something,” said Abernathy. The crowd slowly drifted into motion, streaming down the street toward the carriage. “Is this typical?”

“It’s the first time I’ve seen something like it, sir,” Sikander said. It didn’t seem to be any kind of religious event; Tzoru shrine processions were celebrations, not protests or rallies. Perhaps that distinction was lost on most Aquilans—secularists and rather smug about it—but as a Kashmiri he’d been raised in New Sikhism and surrounded by Hindu friends and acquaintances. That didn’t make him an expert on Tzoru public displays, but it did mean that he was not as quick as his Aquilan comrades to assume that religious beliefs were at the root of any inexplicable or belligerent behavior. He looked up at the carriage driver, activating his translator. “Excuse me, driver—who are those Tzoru over there?”

“They are warumzi agu,” the driver replied. “I did not know that there would be a gathering at this hour.”

“What are they going on about?” Mason Barnes asked.

“They are praising Ebneghirz,” the driver repeated. The name seemed familiar to Sikander. He thought he might have seen something about it in recent intel summaries—a passing mention, perhaps. The Tzoru Dominion simply didn’t have any kind of media culture, and finding out what any large number of Tzoru thought about something was surprisingly difficult. The driver seemed annoyed rather than concerned, but of course that might mean anything. On the other hand, it only took Sikander a few moments of watching to decide that he didn’t like the look of the crowd at all. He’d never seen a Tzoru mob in person, but he’d seen more than a few human ones, and something about this group shouted danger! at him.

“Driver, are they angry at us?” he asked directly. Sometimes that was necessary to get a Tzoru to consider a situation outside of his or her own narrow interests.

It worked—the driver glanced down at Sikander, back to the warumzi agu procession, and back to Sikander again before nodding. “They may be,” he conceded. “Honored friends, it would be better if we went a different way.” He made a clicking sound at the alliksisu and touched its flank with a long, reedlike goad, turning the creature toward a cross street before the crowd reached them. Driving an alliksisu carriage seemed to involve a good deal of suggestion and persuasion, and few actual controls.

The Tzoru leading the crowd caught sight of Sikander and his companions in the carriage, and suddenly raised their voices in excitement. “I think that’s a good idea,” Abernathy said. He and Reyes occupied the rear seat of the carriage, so they now had their backs to the crowd; the wiry commodore twisted in his seat, scowling at the approaching Tzoru. “Driver, get us out of here.”

Francine Reyes glanced back as well, then keyed her comm device. “Exeter shuttle, this is Captain Reyes. Stand by for immediate retrieval of our party. We have a situation developing.”

“Ma’am, the Tzoru authorities will never permit an overflight,” Sikander said.

“I don’t intend to ask them,” said Reyes. “Better to—oh, damn.”

Behind the carriage, the leading ranks of the warumzi agu broke into a run, bounding after the carriage in short, springy strides that swallowed up the distance with alarming speed. “Look out!” Sikander shouted. He rose from his seat and crouched upright in the carriage, ready to fend off anyone trying to climb aboard. He had no idea if unarmed combat against a Tzoru was a good idea or not, but he’d rather go down swinging if it came to it. Mason Barnes followed his lead, and got up to guard the other side of the carriage.

“Exeter shuttle, come get us!” Reyes shouted into her comm unit.

The carriage driver flicked his goad again, and the alliksisu fell into a clumsy trot … but the mob continued to close the distance. Some of the warumzi agu drew close enough to pelt the humans with small stones, bottles, and even round, hard fruit of some sort, an angry hail that clattered against the metal sides of the carriage or bounced back into the street. Sikander ducked and raised a hand over his head to protect himself—and then a fist-sized bottle sailed out of the crowd, striking the driver in the back.

The driver gave a sort of whistling hiss and suddenly abandoned his post, leaping down to the street and scuttling away. “Do not hurt me!” he shouted before the translator lost his voice. Sikander caught a glimpse of the fellow scissoring his hands in front of him and bowing as he hurried off, a Tzoru gesture more or less equivalent to a human raising his hands over his head. The pursuing Tzoru swarmed around him; several began to tear at his robes and pummel him savagely.

Confused, the alliksisu began to slow again—and then something else was thrown into the carriage, a clawed creature about the size of a large rat. It had a spiky carapace and a barbed tail equipped with a jabbing sting, and it scrabbled about the floor of the carriage, clacking its mandibles. All four humans flinched away from the repulsive little monster.

“What is that?” Abernathy snarled.

Sikander had no idea, but when the creature darted after Reyes, he saw his opportunity. He stepped forward and swung his right foot through the creature in a magnificent soccer-style kick that punted the thing a good six meters through the air. It disappeared into the crowd. At the same time, Mason scrambled up over the passenger bench to the driver’s position, seized the slender goad, and whacked the alliksisu across the rump with a blow so forceful that Sikander heard the crack! above the shouting and screams all around them. The draft beast let out a roar of pain and bolted away, throwing the passengers back into their seats and scattering the crowd surrounding the carriage. Sikander lost his balance completely and fell heavily onto Abernathy and Reyes.

By the time he extricated himself from his superiors, the mob of green-capped Tzoru had fallen far behind. Barnes stood in the driver’s position, guiding the galloping beast with the goad. He managed to coax the alliksisu into turning down a cross street, and let it gallop on for a few hundred meters. Astonished Tzoru stopped in their tracks to goggle at the carriage and its human occupants racing past. Sikander ignored them and kept watch on the street behind the carriage, making sure the mob couldn’t catch up to them.

“Mr. North, any sign of pursuit?” Abernathy said, raising his voice to be heard over the draft beast’s bellows of protest and galloping footfalls. Sikander noticed that at some point in the encounter the commodore had lost his gold-braided cap.

“They gave up two or three hundred meters back. I think we’re clear for now, sir.”

“Very good. Mr. Barnes, see if you can slow this thing down before we flip the carriage or run over somebody. D-Com, cancel the shuttle, if you please.”

“Exeter shuttle, belay your orders,” Reyes said into her comm unit. “We are no longer in immediate danger.”

“Yes, sir.” Mason glanced around the driver’s post, and carefully adjusted a lever. The carriage magnets changed their orientation, applying a smooth braking resistance to the alliksisu. The beast immediately responded to the signal, slowing to a walk.

“Well done,” Abernathy said. “When in the world did you learn to drive one of these ridiculous things, anyway?”

“I’m Hibernian, sir. Not the first time I drove a horse-drawn carriage. Or whatever the Tzoru call their horses.”

The commodore snorted. Hibernia had a reputation for being rural and backward, at least by Aquilan standards. “It would seem so. Now, where is our embassy again?”

“I know the way, sir,” Mason replied. “We’re not that far off. But shouldn’t we go back for the driver?”

“Of course not,” Abernathy said. “If he didn’t want us to leave without him he shouldn’t have abandoned his post in the face of danger. Mr. Barnes, the embassy, if you please.”

“Yes, sir.” Mason applied the goad again, gently this time. The draft beast picked up its pace; the lieutenant guided it onto another crossing avenue, and settled into the driver’s position. He looked ridiculously out of place, but he seemed to have the draft animal under control.

“Very good. Now someone explain to me what just happened there. Who are these Warzi Gooey fellows? Why did they chase us? Mr. North?”

“I’m not sure, sir. I think it’s some kind of popular movement—the Tzoru have a lot of them, but nothing that makes it onto our threat assessments.” Sikander shrugged helplessly. “I’m afraid the only intelligence the squadron staff collects on local civilian matters is what the Tzoru report on their own broadcasts.”

“That’s not good enough,” Deputy Commodore Reyes said to Sikander. “You should review local conditions with the embassy before we even set foot on the ground, Mr. North. An intelligence officer is supposed to anticipate trouble, especially when a flag officer’s personal safety may be at risk.”

Sikander bristled, and barely succeeded in fighting down a sharp retort. In the first place, it was not a fair criticism—local developments weren’t really part of his job as squadron S-2. His team focused on the formations and capabilities of the Tzoru military sebetu, as well as the squadrons of half a dozen other human powers that maintained a presence in Tzoru space. Tzoru politics were complicated, and even the expert diplomats of Aquila’s embassy had trouble interpreting events here. Secondly, he didn’t care at all for Reyes making a point of criticizing him to their new commanding officer. She’d done enough of that with Commodore Morse; the last thing he needed was for her to continue that sort of harassment now that Commodore Abernathy had assumed command.

Unfortunately, arguing against a superior officer’s criticism rarely improved matters. So instead he said the only thing he could in reply: “Yes, ma’am. I will touch base with our embassy staff.”

Commodore Abernathy let the exchange pass without comment. Instead he made a show of studying the ancient walls surrounding the Thousand Worlds ward, now coming into view, and gave his stiff mustache a small tug. A note of approval, or disapproval? Sikander wondered. For a man who carried himself with such energy and wasn’t shy about sharing his opinions, William Abernathy could be surprisingly hard to read at times.

Mason tapped the alliksisu on its flank and turned the creature and the carriage to the right, passing beneath the ceremonial gateway leading into the Thousand Worlds ward. The ancient fortifications rose up around them, then gave way to a crowded district of homes and workshops and mercantile establishments huddled together within the old walls. More floating alliksisu-drawn carriages crowded the narrow streets, but here human diplomats and businesspeople mingled with Tzoru servants, shopkeepers, and retainers in the service of one or another of the noble clans. No less than nine different human powers maintained embassies in the Thousand Worlds ward, not to mention a sprawling Nyeiran mission and a Velar consulate hidden in one of the back alleyways. In eight square kilometers of the old walled district, humans and nonhumans from almost all of civilized space met and interacted with each other in a disorderly, chaotic cauldron of activity.

“Here we are, Commodore,” Mason announced. He guided their draft beast into a circular driveway in front of a sprawling building—recent human construction, not ancient Tzoru—that reminded Sikander of the governor’s mansion on New Perth. Aquilan marines in dress uniforms stood watch by the main entrance; their crisply pressed uniforms were much the same as the ones their predecessors had worn for centuries, but the mag rifles at their sides were brand new and very, very functional.

“Very good,” Abernathy grunted. He stood and hopped down from the seat without waiting; Sikander and Reyes followed, while Mason handed the goad to a Tzoru attendant who hurried up to relieve him. Sikander took a moment to check his uniform for any unsuspected tears or marks, and discovered a section of ripped seam along his side and a purple stai

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...