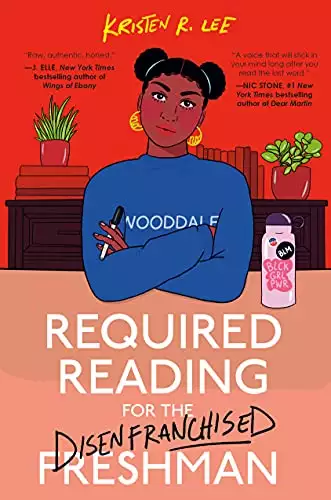

Required Reading for the Disenfranchised Freshman

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Savannah Howard sacrificed her high school social life to make sure she got into a top college. Her sights were set on an HBCU, but when she is accepted to the ivy-covered walls of Wooddale University on a full ride, how can she say no?

Wooddale is far from the perfectly manicured community it sells on its brochures, though. Savannah has barely unpacked before she comes face to face with microagressions stemming from racism and elitism. Then Clive Wilmington's statue is vandalized with blackface. The prime suspect? Lucas Cunningham, Wooddale's most popular student and son of a local prominent family. Soon Savannah is unearthing secrets of Wooddale's racist history. But what's the price for standing up for what is right? And will telling the truth about Wooddale's past cost Savannah her own future?

A stunning, challenging, and timely debut about racism and privilege on college campuses.

Release date: February 1, 2022

Publisher: Crown Books for Young Readers

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Required Reading for the Disenfranchised Freshman

Kristen R. Lee

ONE

The pizza drivers don’t deliver here after seven.

Five in the wintertime, when the sun sets earlier. When they do deliver, they don’t come beyond the iron gates of my building. We have to walk down to them. They park damn near around the corner, but they still expect a tip.

I have a tip for them: stop being afraid of Black folk.

I search for my low-top Air Force Ones that I’ve been wearing since ninth grade. Mama taped up the bottom with duct tape to keep the soles from falling apart. She tells me all the time to throw them away, that no matter how poor we are, we don’t have to look it, but I can’t toss them. These same shoes took me everywhere, and in a few days they’ll be coming with

me to college. A college I’ve worked my whole life to get into but, truth be told, I don’t want to go to. Not like Mama would give me a say anyway.

“Mama, I’m finna go get a pizza.” I stand behind the bedroom door that hangs off the hinges. She takes her sweet time inviting me in. I know better than to enter her room without permission.

“Bring me a pepperoni with extra cheese,” she says.

You got extra-cheese money? I want to say, but I don’t have time for a lecture. I lean against the wall. “You know they charge more for the extra cheese, Mama?”

“I know that, Savannah. Come get twenty dollars out my pocketbook.”

The door hugs my body as I rest against the wall. Mama sits on the edge of her bed, and the cutoff shirt she wears shows the aging in her arms. Soft pink rollers that give her hair a “bump” peek out from underneath her bonnet. Her swollen feet rest in one of them massage buckets boosted from Walmart by my cousin Shaun. Mama’s feet ain’t no good anymore. Years of standing up on concrete at a warehouse for twelve hours did a number on her body. When she got that good job down at the tax agency, she ran into the house and threw out every pair of steel-toe boots she ever owned. But by then the damage to her feet was already done.

“Don’t be out too late. It ain’t safe.” She gives the same warning each time I step outside. Even if I’m only going toward the back of the apartments to throw out the trash.

“Mama, it’s right up the street.” I pause. “Besides, you can’t keep an eye on me after I’m at college.”

It feels funny saying that. Me? College? I’m only seventeen—well, seventeen and a half. One minute I was doing accelerated-learning courses, then dual-enrollment classes, and then the guidance counselor talking about I’m ready for college, if I want to go. I worked like a senior my sophomore and junior years to apply to the best colleges—like Wooddale. Getting into Wooddale meant I made it. That Mama working them long hours wasn’t in vain. While my homegirls went to parties, I was prepping for the SAT night and day. It worked because I got a 1500 and accepted to every college I applied to, including the HBU down the street. But Mama said I’m not going to that one because it won’t make me successful. Even though people who graduate from HBUs do big things too.

She said I need that fancy Ivy League degree.

And I mean, she right. Life would be so good then. If I got a good enough job with that Wooddale degree, we could even move. Mama wouldn’t be worried about crime or nothing. Bet wherever we move then, the pizza people would deliver all the way to the doorstep.

Mama points her half-polished finger at me. “You heard what I said. I don’t wa

nt you walking them streets this late at night.”

I reach into her purse and pull out an Andrew Jackson. I crumple it up and put it in my bra. Mama taught me to never stick money in my pockets. It’s the first place robbers look.

“Aight, Mama. Yes, ma’am.”

I walk down the stairs and exit my building. Little kids sit out in the patches of brown grass playing hand games with silly chants. I grin. It reminds me of my own childhood.

Summer as a kid was lit.

Staying out all day, riding my bike with the pink tassels coming out the handles. Playing jacks on the porch, if you can call the slab of concrete that. Next day I would wake up and do the same thing over again until school started up in August. Then for at least eight hours I was guaranteed two meals and an air-conditioned place to stay.

My Wooddale degree gone change that, too.

“Savannah, wait up.” B’onca, my homegirl since grade school, runs over from the basketball court. “I ain’t know you’d be ready so soon. Where we going anyway?”

Meeting B’onca to say my goodbyes is bittersweet. We as good as sisters. Our mamas were best friends growing up—they still are. When you see B’onca, you see me, and vice

versa. Pictures of us from pigtails to our first grown-up wraps decorate our refrigerators.

“Figured we’d get pizza.”

“Oh snap, pizza? That’s fancy.” She wipes her chiseled face with the bottom of her shirt. “Your mama must got her food stamps.”

“Nah, we got cash money today.” I pat the soft spot in my bra. “We getting Marco’s. Real pizza. Not from the corner store.”

“Cool.” She looks behind her at her building. Her brows meet. “But I gotta be home…soon.” Sweat glistens across her chest, and her ombré black-and-brown dreads fly in the wind behind her. She’s in the National Honor Society and used to play ball, and not only basketball, neither. Her grades are as on point as her jump shot. B’onca soared in everything she did. Then, in high school, she met Scooter, her boyfriend, and quit all sports. Scooter says his woman ain’t gone be “manlier” than him. I told her that’s wild, but she in love, and love overrule anything I have to tell her.

“You good?”

“Yeah. But hold up, one minute.” She sprints to the court and picks up her basketball. Scooter must not be around. If he was, she’d be at his house playing wifey. Cooking him

chicken, watching Netflix, and folding his drawers. Her nose wide open, like the old folks say.

My foot taps the pavement as her teammates try to convince her to stay and play. If you got B’onca on your team, ain’t no way you losing. She runs over, dribbling. “Aight, let’s go. We good.” She catches up to me. “You sure you need pizza?” She pinches the rolls in my stomach, and I slap her hand away.

“Fuck out of here. I’m depressed and food helps.”

She twirls her basketball around on her middle finger. “Shoot, depression a white-folk thing. You just sad you leaving me, that’s all.” B’onca kicks at a stray hot-fry bag on the sidewalk. “ ’Cause I know you not sad you leaving this ghetto-ass place.”

“I’m only seventeen, B. What I know about college? Living on my own?”

“With how much your mama works, you’ve been practically living on your own since you were what? Fourteen? It ain’t gone be that different. Just this time your mama and best friend”—she nudges me with her elbow—“won’t be right up the street.”

Five months ago when I got the acceptance letter in the mail, Mama musta hollered somethin’ fierce. The next-door neighbor, Mrs. Hall, ran over with her walking cane. She

waved it in the air, ready to fight off intruders. She did the same shit when the financial-aid package followed.

“A full scholarship!” I can still hear the Mariah Carey level of Mama’s scream. That’s what my lack of a life in high school got me. And even I couldn’t fight the tears that day, opening the mail. I’m proud. I have something nobody round here has ever had. Something I haven’t seen nobody who look like me do.

Both letters are on the refrigerator, placed behind old Shop & Save grocery coupons and Pillsbury Doughboy magnets. Wooddale’s acceptance letter covers the one from Hilbert. Hilbert University, the local historically Black college ten miles away. Mama said it would be real foolish of me to turn down a paid-for university like Wooddale for a school that can’t even afford financial aid for every student. Wooddale one of the top schools in the country, while Hilbert don’t even make those kinds of lists.

She doesn’t understand, though, that my friends from the neighborhood and folks who resemble me attend Hilbert. I scrolled Wooddale’s Instagram hashtag the other day and counted on one hand the number of Black folk posting pictures. They don’t look like the type of folks I’d hang out with. But I want to make my family proud of me—especially Mama.

Where I’m from, folks can be successful if given half the chance. Hair braiders stand on

their feet all day in their kitchen beauty salons, creating styles just as good as anyone with a real beauty shop. Little girls have singing contests on their stoops and sound better than anyone on BET. Women plan extravagant birthday parties for they babies with twenty dollars and a dream. Dreams don’t pay overdue water bills, though.

“Two thousand dollars for a one-bedroom apartment.” B’onca kicks the plastic real-estate sign and it falls over. “That’s more than my mama make in a month.”

“These apartments ain’t for us,” I say.

We pass an empty construction site. Yvonne’s Beauty Bar and Mike’s Grocery next to it are both chained up for the night. The street full of Black family-owned businesses that have been around way before I was ever thought of. At the corner is a clothing boutique named Elegant, where I got my eighth-grade prom dress. Across from it is the liquor store with the missing L in the sign. Folks always going in and out, brown paper bags in their hands.

The bell dings as we walk into Marco’s, and the scent of garlic swells in the air. A clerk behind the counter writes down orders and takes phone calls. He got acne deep as craters across his face, but he can’t be any older than us. Marco’s is family-owned like Yvonne’s and Mike’s, but they Italian. The namesake bought the store for cheap a few years ago and

monopolized the hood pizza game. We stand behind the wooden barrier with the Italian flag folded across it for five minutes and the cashier don’t even say hello.

Ten minutes later it’s the same silence.

“Aye, boy, you see us standing here,” B’onca shouts as she slams her palm on the counter, causing the clerk to jump. She always on ten.

“We want to place an order,” I say, reminding him of his job description.

He sighs and slides a folded pizza box out of sight. “What do you want?”

I lean my elbows on the counter. “Hello to you, too.” I squint at his name tag. “Jason.”

He kisses his teeth in annoyance. I would leave right now, but this the only shop within walking distance. I don’t want Tony’s frozen pizza from the Shop & Save. I want the real thing, and since they set up shop in our neighborhood, ain’t they supposed to serve the people in it?

Ignoring his bad attitude, I place my order. “Could I please have a large pepperoni with extra cheese?” I reach into my shirt and unfold the twenty.

“Sorry,” he says with no hesitation. “We’re out of pepperoni.”

“What about sausage?” I hate sausage, but I hate being hungry even more.

“We’re out of that as well.” This time a smirk paints his face and I know

he’s lying, and I know why. The why always make my stomach hurt.

B’onca fakes a hearty laugh before her face changes. “Now how the fuck you out of pepperoni and sausage? This a pizza shop, ain’t it?”

I try to give her a look to simmer down, but B’onca ain’t trying to hear that.

“I don’t have to serve you if you’re going to act belligerent.” Jason folds his arms across his chest.

“How are we acting belligerent?” I look around the shop. “You made us wait fifteen minutes. You can’t be that busy. Ain’t nobody here.”

His face becomes light pink. “Please leave or I’m going to call my manager.”

B’onca ignores his threat and gives him the finger. “My friend wants pizza and it’s your job to serve her.”

He walks over to the ancient landline phone that hangs on the wall and grabs the receiver. “I will call the police. Don’t try me.”

“Call ’em,” B’onca says as she dials 911 on her own cell phone. She flashes the screen to him. “I’m ahead of you.”

“Come on, B. It ain’t worth it.”

There ain’t no point in arguing with Jason or none of these other shops that pop up every day. To them, we only rowdy Black kids, and that is all we will ever be.

“This not right, Savannah,” she says. “He ain’t want to serve us no way.”

“It’s cool. We can go to the grocery store and get frozen. Better than this shit they serve, anyway.” I ball up a half-off-pizza flyer and throw it across the counter.

Jason walks to the door, and before it shuts good, he flips the OPEN sign to CLOSED. Even though it’s only six-thirty p.m.

A strange look settles across B’onca’s face.

“B?”

She ignores me, looks both ways, and crosses the street to where a sanctuary of rocks is piled.

I walk to the edge of the curb. “Girl, what you doing?”

She grabs one and sprints toward Marco’s.

Shit. “B, it’s aight, for real.”

Through the glass, the clerk’s nasty attitude gets replaced with a toothy smile. He stares at us while he yaps on the phone.

“He don’t wanna serve us ’cause we Black, but he want to rent space up in our neighborhood. I can’t stand these damn folks, acting like they own everything and everyone.” Stepping forward, she tosses the rock up and down in her hand and motions for me to move aside. I hesitate, fully aware of what’s about to happen. I got accepted into college five months ago. Do they let you defer if you get locked up? Is there a program in jail that lets you out for being a good student? Because if B going down, they gone snatch my ass too, that’s for sure. I never heard of no Black person being let out early on good behavior.

B’onca never think shit through. She smart and got more talent in her pinky toe than most folk, but she don’t think. She let her feelings eat her up, and later she always regrets the things she’s done.

“B, don’t. Seriously. It ain’t worth the trouble.”

“Don’t act like he don’t deserve it,” she says.

He does, but that ain’t gone matter when the police got us facedown on the concrete in handcuffs. The salty taste of sweat pours down my face. Every moment that passes feels like I’m a moment closer to the prison three streets over.

I try to take the rock from her hand. “Let’s just get going. Get pizza somewhere else.”

For a moment, nothing. Then she drops the rock and I can breathe again.

“They better have the double-pepperoni pizza too,” she says as we walk toward the grocery store.

A young couple approaches us, and from the look of fear on their faces, they don’t belong here. From the color of their skin to their fluffy dog, they don’t belong here. I see them around every now and again. People like them walk their pups up and down the block in the evenings but stay clear of the hood. They live in apartments with coded gate pads and covered parking.

The couple brushes past us and the woman barely touches my shoulder.

“Excuse me. I’m so sorry,” she fumbles, and does that fake grin with no teeth, her eyes wide.

I re-create the same smile. “No problem.”

She says sorry one last time before they continue their walk.

“She thought you was gone beat her ass about an accident?” B’onca asks, swishing her braids.

“Prolly. You see her shirt?” She’s wearing a V-neck Wooddale shirt. I don’t know if it’s a prophecy or an omen.

“You’ll be inside those gated communities in a few years. Looking down your nose at us behind the iron gates,” B’onca says.

An omen if I ever heard one. “Those are the type of people who go to Wooddale. Look at them. Now look at me.” The woman has gold jewelry that doesn’t turn her skin green after wearing it two hours too long. She walks like Earth’s rotating just for her. I don’t fit in with people like that. Not with my cubic zirconia and slouched shoulders. Even with my Wooddale shirt on, they’d think it was a gift or a find at Goodwill, not that I actually attend the school.

“You need to stop thinking all negative.”

“I’m being real. Mama may think I’m some unicorn, but I’m not.” The couple is almost a dot in the distance, but I can’t look away. They hold hands, giggling as they walk along the trashed curb. They step over Jolly Rancher wrappers and prescription bottles like they’re nothing; may as well be flowers. Everything coming up roses in their eyes.

“I’ll never be them. And they’ll never know what it’s like to be me.” Man, this too much. “I ain’t even hungry no more.” I switch directions and B’onca follows, the Shop & Save and Marco’s behind us. She drapes her arm around my shoulder as we walk.

“Girl, boo,” she says. “Go to that fancy school and get your expensive-a

ss sheet of paper. Come home and help your hood out.”

“You coming with me next year, right?”

That was the plan, kind of. We were supposed to attend Hilbert together, join a sorority together, and dorm together. The location changed, but the plan remains the same.

“Now you know I can’t get in that fancy school. You have the book smarts.”

I squirm from underneath her arm, the couple now invisible in the distance. “I can help the hood more if I actually stay here.”

B’onca turns around, walking backward. “Shit, the way that lady had her purse all open, she was ’bout to help somebody in the hood hit a lick.”

“Did you see the dude’s watch?” I ask. “I know that’s real gold.”

“Truth.”

Our projects come into sight and we promise to call each other later, one last so long before home is in my rearview. B’onca dribbles off and disappears from view. Our apartment is on the second level, and I’m good and out of breath by the time I hit the landing, no matter how many times I’ve walked them stairs. I step inside and head straight to the kitchen and pour myself a glass of water from the tap. It’s warm, but still cools down my heart rate.

“Where the pizza?” Mama asks.

She’s at the counter reading through the same Wooddale brochure that I’m sure she can recite verbatim by now.

I halfway lie. “They were closed today.”

“Damn, I had my mouth all set for some pizza too.”

“I can make us some bologna sandwiches.” I set out the bread. The expiration date says five days ago, but ain’t no mold on it.

“That’ll do.” She smiles down at the brochure. “They got a Black woman as president of the university. Ain’t that something?”

“Yes, Mama.” We’ve been through this process a hundred times.

“Uh-huh. Remember that lady I used to do bookkeeping for? With the kids you used to play with sometimes while I worked.”

I couldn’t forget. During tax season seeing Mama was like spotting the Loch Ness Monster.

“She went to Wooddale. Had the biggest house on the block. Own car, paid for in cash. Now my baby is going there. That’s going to be you someday.”

“There’s plenty of successful people who went to Hilbert,

too. Lawyers, doctors, and businessmen right in our community.”

People try to play Hilbert. Just because it’s in the hood and Black, they give the school a bad rep. I just know I’d be happier there, with people who understand me, but it’s like my happiness went out the window soon as that acceptance letter came.

Wooddale’s letter stares at me as I open the fridge. I take it down and go over the words for the hundredth time.

Welcome. Congratulations. Proud.

In my hands is a thin piece of paper that represents hours of missed sleep, unattended parties, long tutoring sessions, and tons of Mama’s money spent.

Rummaging through the cabinets, I find the cast-iron pan and place it on the stove. The four slices of meat sizzle when they hit the pan. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...