- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

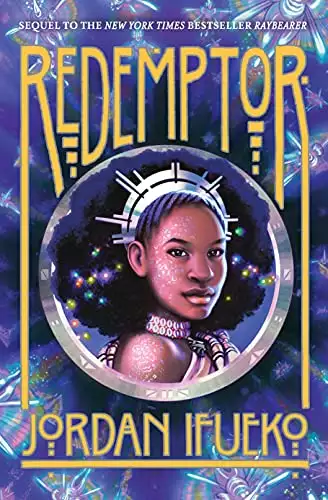

The hotly anticipated sequel to the instant New York Times bestselling YA fantasy about Tarisai’s quest to change her fate.

For the first time, an Empress Redemptor sits on Aritsar’s throne. To appease the sinister spirits of the dead, Tarisai must now anoint a council of her own, coming into her full power as a Raybearer. She must then descend into the Underworld, a sacrifice to end all future atrocities.

Tarisai is determined to survive. Or at least, that’s what she tells her increasingly distant circle of friends. Months into her shaky reign as empress, child spirits haunt her, demanding that she pay for past sins of the empire.

With the lives of her loved ones on the line, assassination attempts from unknown quarters, and a handsome new stranger she can’t quite trust … Tarisai fears the pressure may consume her. But in this finale to the Raybearer duology, Tarisai must learn whether to die for justice … or to live for it.

Release date: August 17, 2021

Publisher: Amulet Books

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Redemptor

Jordan Ifueko

CHAPTER 1

My name was Tarisai Kunleo, and no one I loved would ever die again.

I stole down the palace hallway, my sandals slapping the words into music—never again, never again. I would play this song until my soles wore thin. Griots, the sacred storytellers of our empire, shaped the histories we believed with their music.

I, too, would sing this story until the world believed it.

Tar? The base of my scalp hummed as Kirah connected our Ray bond, speaking directly into my mind. Are you all right?

Kirah, my council sister, and Mbali, the former High Priestess of Aritsar, stood ahead of me in the broad palace hallway. I caught up to them, smiling manically before remembering that they couldn’t see my face.

We wore ceremonial veils: colorful beads and shells that dangled to our chests, concealing our faces. Tall leather hairpieces, stained crimson and shaped into flames, circled our heads. Our costumes honored Warlord Fire, creator of death, and disguised us as birinsinku: grim women of the gallows, on our way to perform holy death rites on imperial prisoners.

I’m fine, I Ray-spoke to Kirah, gritting my teeth. Then I willed my voice to be light and chipper, speaking aloud for Mbali’s sake. “Just—you know. Excited for Thaddace.”

Servants and courtiers danced out of our way as we swept through An-Ileyoba Palace. Rumor warned that birinsinku spread foul luck wherever they went, and so as we passed, onlookers warded off evil with the sign of the Holy Pelican. No one guessed that I, Mbali, and Kirah hid beneath those glittering veils, plotting to free the most hated man in Aritsar from prison.

Dayo had named me Empress of Aritsar exactly two weeks ago. Until then, the world had believed that only one Raybearer—always male—existed per generation. The Ray was a blood gift, passed down from Aritsar’s first emperor, Enoba the Perfect. Its power granted emperors near immortality, and allowed them to form a council of bonded minds, uniting the sprawling mega-continent of Aritsar.

But Enoba had lied about the gift in his veins. He had never been meant to rule alone, for two Rays existed per generation—one for a boy and one for a girl. That Ray now swelled in my veins, upsetting five hundred years of Arit tradition. My sex alone had made me plenty of enemies, but if that hadn’t been enough . . . with one impulsive vow, I had placed the entire empire in grave danger.

For eras, demons called abiku had plagued our continent, causing drought and disease, and stealing souls down to the Underworld. Enoba achieved peace through a treaty, sating the abiku by sending children into the sulfurous Oruku Breach—two hundred living Redemptors, or sacrifices, per year. I had voided that treaty, offering myself instead as a final Redemptor. The abiku had accepted on one mysterious condition: Before I descended to the Underworld, I had to anoint the rulers of all twelve Arit realms, forming a council of my own.

They had given me two years. If in that time I failed to anoint a council and cast myself into the Oruku Breach . . . the abiku would raze the continent. No one would be safe then, not even the priests in their lofty temples, or the bluebloods in their gilded fortresses.

Enraged, the nobles had plied me with tests. If my Ray was fraudulent, my promise to the abiku could be voided, and the old treaty reinstated. But before hundreds of gaping courtiers, I had walked across hot coals, chugged goblets of pelican oil, and submerged my face in gourds of holy water—all tasks, legend had it, highly lethal to any but a Raybearer.

The strongest proof of my legitimacy, however, shimmered in lurid patterns on both my forearms: a living map of the Underworld, marking me as a Redemptor. The abiku would not have accepted my treaty, relinquishing an eternity of child sacrifices, for anything less valuable than a Raybearer. To win my soul, the abiku had made a promise—and a deal made by immortals, once sealed in blood, could not be broken.

Dayo had begged me not to provoke the nobles further. “Just for a while,” he had pleaded. “I want them to love you, Tar. To see you as I do.” Out of guilt for making him worry, I had promised to keep my head down. And I would. Really.

Right after I broke an imperial traitor out of prison.

The late morning sun glowed through An-Ileyoba’s unglazed windows, casting arch-shaped halos on the rainbow floor tiles as I swept through the palace with Kirah and Mbali. A song wafted from the courtyards outside. Courtier children chanted with morbid glee, watching as Imperial Guard warriors erected an executioner’s platform.

When you meet Egungun, will you have your eyes-o?

Tell me, will you hear him, if you have no ears-o?

Dead man, dead man, fell like a coconut

Round head rolling

on the red hard ground.

Brats, Kirah Ray-spoke soothingly, sensing my anger through our blood bond.

I hunched my shoulders. Arits believed that upon death, all souls followed after Egungun: the first human being, born of Queen Earth and Am the Storyteller. Egungun roamed the Underworld beating a drum, leading souls in a parade to the paradise of Core. Those children were mocking Thaddace, who faced beheading in a matter of hours.

The former High Judge of Aritsar had done the unspeakable, an act that until two weeks ago, many had believed to be impossible: For the first time in five hundred years, an Anointed One had murdered his own Raybearer.

But Thaddace had only acted as my mother’s puppet, killing Olugbade in order to save Mbali’s life. I had revealed Thaddace and Mbali’s relationship to The Lady, giving her leverage to force his hand, and so ultimately . . . this was all my fault. Besides, Thaddace was mine. Like my council siblings, and High Priestess Mbali, and Melu the alagbato. Even Woo In and Kathleen, my mother’s Anointed Ones, held cherished places in my story.

I had pined my whole life for a family. Now that I had cobbled one together, dysfunctional and cursed as it may be . . . nothing would snatch it from me. Not even an imperial execution.

I forced my brow to relax. If my plan with Mbali and Kirah succeeded . . . Thaddace would not dance for Egungun anytime soon. Laugh at those children, I told myself. Float, confident that you will win in the end.

But an intrusive thought shook my resolve: Isn’t that what your mother would do?

My jaw hardened. For too long, Aritsar believed girls could only be two things: virtuous servants of the empire, or devious villains, like The Lady. But it was time I silenced those voices.

My lioness mask lay hidden against my chest, a bump protruding from beneath my wrapper. My fingertips warmed as my Hallow summoned hazy memories of Aiyetoro, the only other obabirin, or empress. She had lived too long ago for my Hallow to retrieve her thoughts. But the remains of her haughty confidence put a spring in my walk. Of course I could rescue Thaddace. Who could stop a divinely blessed Raybearer? Who could keep the sun from rising?

You are Tarisai Kunleo. And no one you love will ever die again.

Thaddace waited in the open-air prison of Heaven, a platform atop the tallest tower of An-Ileyoba. Kirah, Mbali, and I had made good time crossing the palace. The corridors were still sparse but for a few sleepy courtiers. Funeral shrouds bundled on our backs concealed supplies to aid Thaddace’s escape. Birinsinku tools completed our disguises—tiny vials of burial herbs and holy water, jingling on our birinsinku belts as we ran.

“We’re going to make it,” I said, laughing in spite of my nerves.

“He won’t accept help,” Mbali warned when we arrived at the steep staircase to Thaddace’s prison.

I shoved down the nugget of doubt in my throat and smiled at her. “Of course he will.” I tried to forget that only yesterday, a servant had slipped me a calfskin letter. The writing had been burnt directly into the hide—a marker of Thaddace’s Hallow.

I have heard of a plot to secure my escape. If these rumors are true, then you are a fool.

I killed an emperor, for Am’s sake.

I was not forced. I was of sound mind, and despite any loyalty you have for me, I am only reaping what I have sown. Your position is precarious enough. Do not join me in my ruin and make Aritsar lose faith in your legitimacy.

I once told you that there is no justice, only order. But I was wrong. Sometimes justice and order are one and the same.

Leave me to my fate, protégé. I join Egungun’s Parade.

Thaddace had not signed the letter. His seal ring had been confiscated, and he had known, besides, that a signature was unnecessary. Every time I touched the calfskin, my Hallow caused the memory of my former mentor’s hands, the sting of his pain and resolve, to chafe my skin. He had likely heightened his feelings on purpose, knowing that they would seep from the paper and coerce me.

“You can convince him to escape,” I told Mbali. “I know he’s worried about ruining my reputation, but we won’t get caught. All we have to do is—”

“He won’t come,” repeated Mbali. “This isn’t about you, Tarisai. He’s only pretending it is.”

We stared up at the landing. Kirah reached for my hand and squeezed. The last time we had stood here, eleven arrows had been aimed at my mother’s heart. The Lady had survived the botched execution, only to be accidentally poisoned by Woo In, her own council member. Beneath her veil, I was sure Mbali looked haunted as well.

“Thaddace was supposed to protect Olugbade at all costs,” Mbali said. “That is the point of being an Anointed One, and why I was ready for The Lady to drop me from this very tower. But Thaddace . . .” She sighed. “He couldn’t let me go. He broke the most sacred vow he’d ever made, and now he feels the universe is owed a debt.”

Cold crept down my arms. “He wants to die?”

Mbali nodded, the beaded strands of her veil clinking together.

“That’s . . .” I sputtered. “That’s insane.”

“No,” Mbali deadpanned. “That’s just Thaddace.”

Kirah crossed her arms. “The High Lord Judge does love one thing more than order, High Priestess. And that’s you. I’ve seen it.”

“You shouldn’t call me that anymore,” Mbali scolded her quietly. “You became High Priestess Kirah the moment Olugbade died. Likewise, Thaddace is not the High Lord Judge. Not anymore.” She shot her mirror-black eyes to me. “The sooner you both embrace your roles, the better.”

Kirah flushed. “Well, I still think you can convince him, High . . . Anointed Honor. When you walk into a room, he changes. You’re his Core.” She used a stubborn tone that I suspected she got from her mother. “And you know it.” Then she held out four gobs of wax.

Mbali looked doubtful, but sighed, shrugged, and plugged her ears. I plugged mine as well, and Kirah cleared her throat and sang into the rafters. The sound was muted, but I recognized the same lullaby Kirah had sung when we first met, waiting for our turn to be tested in the Children’s Palace.

Even with my hands clapped over my plugged ears, the jangling timbre of Kirah’s voice seeped into my limbs, reminding them of how tired they were. Of how sweet it was to rest. How surely a nap, even here on the cold tiled floor, was precisely what I needed . . .

I shook my head and hummed a counter tune, clearing the fog from my mind. The guards at the top of the stairs were not so lucky. When their shadows appeared on the steps, the four warriors were hunched with exhaustion, yawning as they squinted down at us. Three made it a few steps before slumping in the stairwell, their spears dropping with a clatter as they began to snore. The last guard seemed to realize what was happening, but before she could cry for help I bounded up the stairs, clapped her head, and stole the last few moments of her memories. Guilt pricked me as she stared at my veiled face, her own washed of emotion.

I gritted my teeth and pressed her temple again, erasing the entire morning, as well as the day before. Years of trying to coax away Sanjeet’s nightmares had taught me that minds were dangerously resilient. With enough context, people could reconstruct their stolen memories, like filling in the missing tiles of a mosaic. If Thaddace was to escape, I couldn’t let guards remember who had helped him.

The guard succumbed to Kirah’s song at last, slumping against me. I laid her gently on the landing, then wiped the memories of the three other guards, taking no chances.

How many days of stolen memories, I wondered, did it take to erase who someone was? Suppose I erased a crucial moment or epiphany—was that akin to murder?

I swallowed hard, trying not to think about it. For the few memories I stole from the guards, Thaddace would survive to make thousands more. That made it all right—didn’t it? Sacrifice of the few for the many . . . I shivered, hating the cursed arithmetic of empresses.

One of the guards wore a necklace of keys; I lifted it over his head and lurched up the stairs. There, behind the iron-barred door that led out to Heaven, stood Thaddace, hands clapped firmly over his ears.

I beamed with relief. If Thaddace hadn’t recognized Kirah’s Hallow in time, we would have had to drag his sleeping body from the tower.

“Anointed Honor,” I said, parting the birinsinku veil, “it’s me. We’ve come to get you out.” My smile faded at Thaddace’s empty stare. A sharp ammonia smell rose from buckets at his feet, and a threadbare tunic, pulled up like a hood over his head, served as his only protection from weeks of beating sun and wind. Livid burns speckled his pale skin. His hair and beard had been recently shorn—more mercy than humiliation, where prison lice were considered. I wondered who had snuck him the razor, and why—though the thought sent me shivers—he had not used it to end his misery.

He uncovered his ears. “I told you,” rasped the former High Lord Judge, “not to come.”

“I’ve never been good at following directions,” I reminded him, and fumbled with the ring of keys, racing through the guards’ stolen memories. An image of the correct key surfaced in my mind. I held it to the lock . . . then yelped and dropped the key ring, sucking my blistered finger.

“Really?” I accused Thaddace, gaping in shock. “Using your heating Hallow on the iron? That’s low, Anointed Honor.”

He said nothing, green eyes dull and sullen.

“You could have melted the whole lock,” I said then, realization dawning. “All this time, you could have freed yourself!”

“I have not spent my life,” said Thaddace in his thick Mewish brogue, “enforcing the laws of this empire to flout them now. In a few hours, I will lay my head on that chopping block. And so help me gods, I will settle my debts at last . . .” He trailed off as his gaze fell behind me, where Mbali and Kirah stood.

The former High Priestess removed her veil. “And what about the debt you owe to me?”

The resolution in Thaddace’s jaw crumbled, like a pillar of salt in water.

“What of your siblings, who have suffered enough?” Mbali asked, reaching through the bars to stroke his weather-scarred face.

They tried to speak without words, eyes filled with mute longing. But no energy crackled through the air—no sparks crossed the space between them.

They don’t even have a mental bond anymore. Kirah Ray-spoke, her horror sharp in our mental bond. I guess their Ray abilities disappeared when the old Emperor died. Tar . . . that just doesn’t seem fair.

No, it didn’t. I was still reeling at how quickly the old Anointed Ones had been stripped of their power. After Emperor Olugbade’s death, Arit law required his council to be permanently exiled from An-Ileyoba so that the our council’s new power would go unchallenged. Olugbade’s Eleven now resided at a cloistered temple just outside Oluwan City. After a complicated series of disguises and bribes, Kirah and I had just managed to smuggle Mbali back into the palace, knowing she was our only hope of coaxing Thaddace from prison.

Thaddace and Mbali can still be together, I pointed out to Kirah, trying to comfort myself as well. They don’t need the Ray to survive.

But I wasn’t sure if I meant it. I thought of my nights with Sanjeet since returning to An-Ileyoba: our bodies pressed into the shape of each other, sugary nonsense drifting between our minds until one of us dropped asleep. I would love him without the Ray, of course. But when I imagined the mental link vanishing, erecting a wall of adamant between our minds forever . . . I shuddered.

Thaddace wept into Mbali’s palm. “I have to stay,” he whispered. “We lived to build an empire. To shape order from chaos, a world where rules matter. If you think I’ve gone insane—”

“I think,” Mbali said bitterly, “that you’re the same fool I fell in love with. The one who thought the right set of laws could save humanity.”

They held each other through the bars, and I realized with frustration that their features were resigned. They weregiving up. They were saying goodbye.

“Laws aren’t everything,” I blurted, stamping my foot like a child. “Even if they keep empires running. Order is not enough.”

Thaddace turned to me in surprise, raising an eyebrow. “Unwise words from Aritsar’s new High Lady Judge,” he said dryly. “You’re still in charge of court cases, you know—even as Empress Redemptor.”

I barely heard him. The tritoned voice from the shrine at Sagimsan rang in my ears, warming every limb. I had never told anyone what had happened that day—when a spirit spoke to mine on the hillside, propelling me on Hyung’s back toward what I thought was certain death. I barely understood it myself. Even now, a fearful thrill shot through my veins as I stammered those words—the ones that had carried me across lodestones.

“ ‘Do not ask how many people you will save,’ ” I said. “‘Ask, To what world will you save them?’ What makes a world worth surviving in?” I nodded at Thaddace’s and Mbali’s hands. “Well . . . what if it’s this, Anointed Honors? What if?”

Thaddace scanned Mbali’s face, drinking her in. Cracks grew in his suicidal resolve.

“Thaddace of Mewe,” I said. “I order you to escape this tower.”

He blinked at me in surprise, but I only smiled. “Obey your empress, Anointed Honor.” I cocked my head. “You wouldn’t want to break the law, would you?”

CHAPTER 2

Thaddace of mewe laughed: a desperate, rasping sound that dissolved into coughs.

“Stand back,” he managed at last, and the iron lock on the grate began to smolder, melting in on itself until the door creaked open. Thaddace gathered Mbali to his chest, gasping beneath her torrent of kisses.

“I’m sorry,” he mumbled against her neck. “I’ve been a fool.”

“My fool,” Mbali agreed. Kirah and I looked awkwardly at our sandals, and after several moments, the former Anointed Ones seemed to remember they weren’t alone. Thaddace glanced at me over Mbali’s head. “Well, incorrigible one? What next?”

“Change into these,” I ordered, pulling an Imperial Guard uniform and dust mask from the bundle on my back. “Then we’ll have to split up. Groups of two are less conspicuous.”

As he changed, I listened at the landing. My pulse hammered when I heard the squeak of a cart, a muffled thump at the bottom of the stairs, and the pattering away of anxious footsteps.

“That was the drop,” I ordered, “Sanjeet said he’d leave a decoy body. Kirah, Anointed Honor Mbali—can you handle dragging the corpse up to the landing?” They nodded. “Good. Once you’ve brought it up, dress it in Thaddace’s clothes. Use the torches to set it on fire, so it looks like a dishonor killing. Then get out of here as fast as you can. By then, Thaddace and I should have reached the palace gates.”

Kirah winced. “What if you get stopped?”

“We’re leaving the palace, not entering. They won’t have reason to search us thoroughly.”

“Still”—Kirah gestured at the sinister charms and holy water vials dangling from my belt—“make sure the guards see those. And the marks on your sleeves. It’s bad luck to touch a birinsinku who has just delivered last rites. Or at least, that’s what people believe.” She smiled thinly. “Let’s hope those guards are superstitious.”

Thaddace planted a last, lingering kiss on Mbali’s full lips, beaming as she murmured against him: “A world worth surviving in.”

His green gaze darted across her face. “Almost there,” he said. Then my old mentor took my ringed hand in his sunburned one, and we disappeared down the landing stairs.

An-Ileyoba was waking up, and the halls had grown dangerously crowded. Courtiers shot curious looks at the masked Imperial Guard and veiled birinsinku woman hurrying through the passageways. My heart hammered.

“We’ll head through the residential wing and cut around to the back gates,” I told Thaddace, keeping my head down. “Fewer witnesses.”

I guessed correctly: The palace bedrooms were sparsely populated, and we were able to run without drawing attention. Just a few more corridors and we’d be outside. Then Thaddace would be through the gates, and I would have one less horror, one less death on my conscience.

“It’s almost over,” I breathed, and then we rounded a corner. A single child stood in the center of the hallway . . . and I gasped in pain.

The Redemptor glyphs on my arms burned, glowing bright blue.

“Greetings, Anointed Honors,” the boy monotoned.

At first glance, I would have said the child was a ghost. But he was flesh, not spirit, feet planted firmly on the ground. Ten, perhaps eleven years old, with matted straight hair and pale skin like Thaddace’s. The strength of the boy’s Mewish accent surprised me. The cold, green kingdom of Mewe was thousands of miles north of Oluwan, but most realms weakened their regional dialects in favor of the imperial tongue, for fear of sounding like country bumpkins. This boy sounded like he had never seen an imperial city in his life. Most confusingly . . . Redemptor birthmarks covered his body. Unlike mine, his glistened purple—the mark of Redemptors who had satisfied their debt to the Underworld.

“Y-you are mistaken,” I stammered. “We are not Anointed Ones. I’m a birinsinku.” The veil hung thickly over my head and shoulders. This boy couldn’t know who we were. Well . . . the marks glowing through my robe might give me away. But Thaddace’s mask was still in place. Either way, we needed to keep moving. I advanced briskly, intending to pass him, but the boy fell to his knees in front of Thaddace, staring up at him with translucent eyes.

“Bless me,” he whispered. “Please.”

“You’re being silly,” I snapped at the child, beginning to panic as the boy clutched Thaddace’s tunic. “Let him go.”

“Please—”

“Shh!” Thaddace hissed, glancing around the empty hall. When no one came to investigate, Thaddace tried to shake the boy off, but the child began to wail: a high, keening sound.

“I don’t like this,” I whispered.

“Can’t be helped.” Thaddace shrugged and sighed. “Transitions of power are always hard on peasants. I’ll just give him what he wants.”

Hair rose on the back of my neck. The child . . . smelled. Not like an unwashed body, but like earth and decay, or the rotting musk of burial mounds, steaming in wet season.

Something was very, very wrong.

Thaddace bent down, holding out his hand to touch the child’s head. “By the power of the Ray, formerly vested in me, I bless—”

I heard the knife before I saw it. The scrape of metal against leather as the boy slipped it from his boot, and the soft, wet hiss as a line of crimson bloomed across Thaddace’s throat.

My vision dimmed as blood soaked Thaddace’s collar, and he sputtered and gasped.

“Run,” he told me, but my feet had lost all feeling.

“Long live the Empress Redemptor,” Thaddace gurgled, hand locked around the boy’s wrist. With a stagger, Thaddace turned the knife back toward the child. The boy did not resist, eerily calm as his own blade impaled him.

Then Thaddace collapsed on the tiles, dead before he hit the ground.

I backed away, shivering from head to toe. No. Thaddace could not be dead. Thaddace was mine, and I was Tarisai Kunleo, and no one I loved would ever . . .

The thought faded to white noise as the boy stood over Thaddace’s body, removing the knife in his own chest. He did not bleed.

“You’re not human,” I whispered. “What are you?” He didn’t look like an abiku. No all-pupil eyes, no pointed teeth or ash-gray skin. Besides, the abiku did not kill humans unless the Treaty was breached, and I still had two years to make my sacrifice. So if not an abiku, then . . . what?

The creature cocked his head. “I am your servant.”

“You killed Thaddace.” The world was spinning. “Why? For Am’s sake, why?”

“Thaddace of Mewe murdered the late Emperor Olugbade,” the creature replied. “The Empress Redemptor was aiding a crown traitor.”

“But it wasn’t his fault,” I sobbed. “My mother made him. Thaddace wasn’t going to die; I was going to save him—”

“The empress must not engage in actions that damage her reputation,” the boy continued. “For our purposes, your image must remain unsullied. You must retain the trust of the Arit populace.”

“Whose purposes?” I shrilled. “Who do you work for?”

His childish features wrinkled, as though I had asked a question for which he had not been fed the answer. “I am your servant,” he repeated. “The empress must not . . .” He took a step forward. I fumbled for a weapon, but my hand found only the trinkets on my belt. With a cry, I unstoppered a vial of holy water and hurled its contents at the boy.

The water would have dissolved an evil abiku, turning it to ash. But the boy merely flinched, staring emptily at his splattered clothes.

“What are you?” I demanded again, seizing his shoulder and attempting to take his memories.

For seconds, all I saw was a long, yawning void. I blinked—this had never happened before. Even babies had some memories, though fuzzy and disorganized. But after a moment, my Hallow managed to salvage the dimmest echo of a memory, lifting it to the surface.

The boy stumbled back from my grasp, his gaze growing suddenly childlike. Unfocused . . . as though recalling a distant dream. “I’m,” he mumbled, “I’m called Fergus. I was born in Faye’s Crossing. Far north, in Mewe.”

“Who do you work for? Who are your people?”

The boy shook his head slowly. “My parents . . . went away. No. They died in battle. At Gaelinagh.”

“Gaelinagh?” I echoed the foreign word, and battle records raced through my memories. “But that’s impossible. The Battle of Gaelinagh was a Mewish civil war, and they haven’t had one of those in centuries. Not since—”

Disbelief stole the words in my throat.

Peace had been established in Mewe five hundred years ago—during the reign of Emperor Enoba. Back when Redemptors were born all over the continent, and not just in Songland.

The Mewish child was sinking before my eyes. The ground was—was swallowing him. My fingers grasped at his clammy pale skin, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...