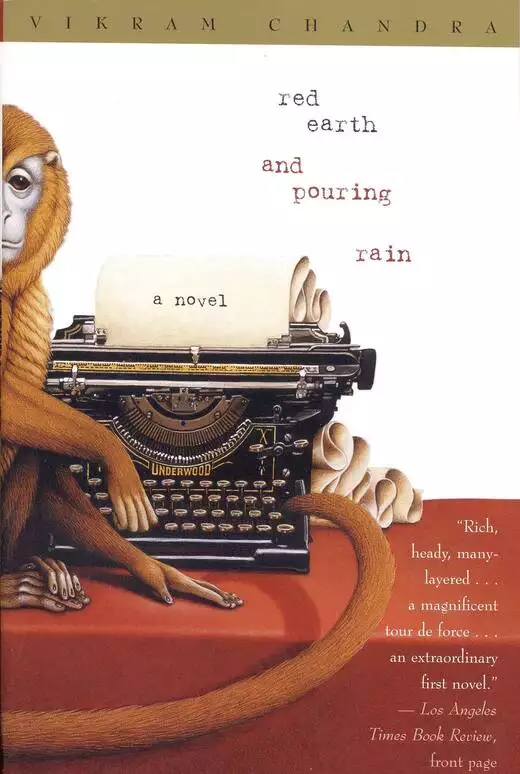

Red Earth and Pouring Rain

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Combining Indian myths, epic history, and the story of three college kids in search of America, a narrative includes the monkey's story of an Indian poet and warrior and an American road novel of college students driving cross-country.

Release date: November 29, 2009

Publisher: Back Bay Books

Print pages: 562

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Red Earth and Pouring Rain

Vikram Chandra

—Long Island Newsday

“Red Earth and Pouring Rain has passages of epic grandeur and desolation worthy of Thomas Mallory…. Chandra is imagining and writing with such originality

and intensity as to be not merely drawing on myth but making it. His imagination is visionary.”

—The Sunday Times (London)

“Wonderfully told, with vividly atmospheric descriptions, appealing minor characters, and interesting insights into the history

and culture of colonial India. Vikram Chandra’s considerable gifts as a stylist shine here.”

—Philadelphia Inquirer

“One of the most accomplished and rewarding novels of recent memory.”

—Houston Chronicle

“Richly textured and engrossing.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Chandra has constructed a brilliantly conceived story line, and this book certainly will help classify him as a premier teller

of tales. The language used by the young author is mesmerizing.”

—Denver Post

“In Chandra’s skillful hands this is an engrossing novel…. Time spent here will be all pleasure.”

—Seattle Times

“Memorable and astonishing.”

—The Literary Review (London)

“Red Earth and Pouring Rain is an important story… in its breadth and scope, theme and style. For those readers open to experiencing the blurring and

complexity of the twice-told and twice-felt, this is a vastly gratifying work.”

—Portland Oregonian

“A dazzling multiplicity of stories… it is the story of more than one nation and century; caught up in its fantastical branches

and glowing imagery are delicate and affecting portraits. Metaphor and prose are melded together with a hypnotic quality”

—The Independent (London)

“This is an exceptional novel…. An astonishing debut.”

—India Currents Magazine

“Magical realism with an Asian-American twist.”

—Library Journal

“Vikram Chandra’s Red Earth and Pouring Rain is, quite simply, good fiction, pure enjoyment.”

—Virginian-Pilot and Ledger-Star

“There is much to admire and applaud in this novel —its playful but always intelligent command of its diverse materials; its

implicit creation of contrasts between different civilizations and epochs; its ability to create a world in which gods, monkeys,

Indians, and Englishmen coexist; and the sheer onward movement of its story, or stories.”

—Times Literary Supplement (London)

THE DAY before Abhay shot the white-faced monkey, he awoke to find himself bathed in sweat, a headache already cutting its way into

his skull in a razor-thin line across the middle of his forehead. He lay staring at the slowly-revolving ceiling fan that

picked up dust with each revolution through the hot air, adding another layer to the black stains along the edges of its blades.

Much later, he rose from the bed and stumbled to the door, rubbing his face with the flat of his palms. As he looked out at

the sunlit court-yard with the slightly-dazed eyes of those who go away laughingly on journeys and return only to find themselves

coming home from exile, his mother swayed across the red bricks, carrying a load of freshly-washed clothes on one hip, and

vanished into the stairway leading up to the roof. In a room diagonally across the court-yard from where Abhay stood, his

father’s ancient typewriter beat out its eternal thik-thik, creating yet another urgent missive to a national newspaper about

the state of democracy in India. A single crow cawed incessantly. Abhay forced himself out into the white, blinding square

of heat, feeling the sun sear across the back of his neck, and hurried across it to the damp darkness of the bathroom. He

stripped off his clothes and stood under the rusted shower head, twisting at knobs, waiting expectantly. A deep, subterranean

gurgle shook the pipes, the shower head spat out a few tepid drops, and then there was silence.

‘Abhay, is that you? The water stops at ten. Come and eat.’

When he emerged from the bathroom, having splashed water over his arms and his face from a bucket, his mother had breakfast

laid out

on the table next to the kitchen door, and his father was peering at an opened newspaper through steel-rimmed bifocals.

‘We could still win the Test if Parikh bats well tomorrow,’ said Mr Misra sagely, ‘but he’s been known to give out under pressure.’

‘Who’s Parikh?’ Abhay said. He could see, in a head-line on the front page of the newspaper, the words ‘terror threat.’

‘One of the best of the new chaps. Haven’t been keeping up with cricket much, have you?’

‘They don’t have much about it in the American press,’ Abhay said. ‘When does the water come back on?’

‘Three-thirty’ said his mother as she emerged from the kitchen bearing hot parathas. ‘I thought of waking you up, but you

looked so tired last night.’

‘Jet lag, Ma. It’ll take a week or two to go away.’

‘Maybe,’ Mr Misra said, folding his newspaper. Abhay looked up, surprised at the sudden quietness in his father’s voice, wondering

how much change his father recognized in his eyes, in the way he carried himself. A quick movement on the roof caught his

eye, and he craned his neck.

‘It’s that white-faced monkey!’ he burst out. ‘He’s still here.’

‘Oh, yes,’ said Mr Misra. ‘He’s a member of the family now. Mrinalini feeds him every morning.’

The monkey hopped onto the roof from the branches of the peepul tree at the front of the house, loped up to the laundry line

and, with a sweep of its arms, gathered up a sari, a shirt and two pieces of underwear, and raced back to the tree. It waited,

firmly seated in the spreading branches, as Mrs Misra went up the stairs and laid two parathas on the wall that ran around

the edge of the roof and stepped back some four or five paces. The monkey, moving with assurance, as one moves during the

performance of a familiar ritual, swung back to the roof, dropped the clothes, seized the parathas, and clambered back into

its familiar leafy territory, where, after it had seated itself comfortably on a suitable branch, it proceeded to eat the

bread, cocking its head occasionally to watch Mrs Misra as she gathered up the clothes and put them back on the line.

‘It’s still terrorizing you after all these years,’ said Abhay. ‘You should do something about it.’

‘It’s just trying to make a living, like the rest of us,’ Mr Misra said,

‘and it’s getting old. He’s moving pretty slowly now, did you see? Forget him. Eat, eat.’

Abhay bent his head back to his meal, but straightened up every now and then to peer at the peepul tree, where the monkey

was intently devouring its daily bread. Somehow, even as he savoured the strangely unfamiliar flavours of his mother’s cooking,

Abhay was unable to shake the conviction that the animal, secure in the cool shade of the peepul tree, was enjoying its meal

more than he was, and that there was some secret irony, some occult meaning in their unwitting sharing of food. The monkey

finished first and sat with its head cocked to the right, peering intently at the family below, a puzzled look on its face.

It scratched at an armpit, turned and swung itself deeper into the recesses of the peepul, stopped and peered at the sparkling

white house with its little square court-yard, and then abruptly slung itself away into the trees on the adjoining maidan.

That afternoon, in the course of his meanderings over the roof-tops of the city, the monkey found himself in a tree on the

maidan again. More out of habit than from hunger, he negotiated his way to the peepul and vaulted onto the roof. Below, Abhay

was seated at the kitchen table, sipping from a glass of cool nimbu pani, speaking haltingly and somewhat formally to his

parents about his travels and times in a foreign land. As the monkey began his customary gathering of garments, he was surprised

to see Abhay jump out of his chair and dash up the stairs to the roof. Moving as fast as his ageing limbs would permit, the

monkey propelled himself off the roof and onto a branch, clutching just one piece of apparel. A moment later, a nasal howl

of pain burst from his lips as a jagged piece of brick shattered into smaller fragments against his rump. Pausing only to

bare his yellowed fangs in the general direction of the roof-top, the aged monkey disappeared into the trees on the other

side of the expanse of open ground in front of the house.

‘He got my jeans,’ Abhay said. The son of a bitch has my jeans.’

‘Well, what did you expect?’ Mrs Misra said, a little stiffly, irritated by the sudden violence inflicted on a member of the

tribe of Hanuman. ‘You scared him away.’

‘Will he bring them back? Cost forty dollars.’

‘No, he’ll probably drop them somewhere and forget all about it. You’ve lost those pants.’

She walked away, into her bedroom. As Abhay descended from the roof, suddenly aware of the perspiration streaming down his

sides and his mother’s displeasure, he felt an old adolescent anger awaken, sensed an old bitterness tinged with resentment

and frustration leaping up again, ancient quarrels and terrors and reasons for leaving raising their heads, unquiet, undead,

effortlessly resurrected.

When the trees extended serrated shadows across the maidan, under a few gaily-coloured kites that hung almost motionless in

the air, tiny bits of red, green, yellow and orange against a vast blue, Abhay walked in a huge circle, over the tufts of

grass and through the teams of barefoot boys engaged in interminable games of cricket. To the south, in the crowded lanes

and bazaars of Janakpur, his past waited, eager to confront him with old friends and half-forgotten sounds and smells. But

Abhay hesitated, nagged by a feeling that he had been away for several centuries, not four years, afraid of what he might

find lurking in the shadows of bygone days, and suddenly he felt his soul drop away, felt it withdrawing, leaving him cold

and abstracted. So he watched himself, as if from a great height, watched himself describe two great circles and then trudge

back into the white house. In the same dream-like state, he watched himself converse with his parents and eat dinner. Much

later, he calmly observed himself scrabbling in the recesses of a cupboard, throwing aside yellowed comic books and once-cherished

novels, to emerge, then, finally, bearing a child’s weapon, a child’s toy, this: a rifle, bolt-action, calibre 0.22, a miniature

weapon, yet sleek and deadly. Hands caress it, linger over its contours, feel the smooth blue-black steel, hands trace the

lines of the heavy wood and test the action, snick-CLACK, these hands that belong to someone not familiar to the members of

the Misra household, these hands that feed the slim golden rounds into the magazine, click-click-click, these hands belong

to a stranger. This stranger sits in a chair next to a window, cradling the rifle, watching the roof. Far away, on the edge

of wilderness, a jackal howls, and the dogs from the city retort, but there is no indication that the figure by the window

hears any of this.

The monkey, propped securely in a fork high up on a banyan tree, was awakened by the first rays of the sun spreading warmth

across his back

and a sudden emptiness in the pit of his stomach. He recalled, fuzzily, having been hungry when the sun last set, but the

encounter with the fragment of brick had already begun to fade into the undifferentiated grey mist that constituted his past.

Ravenous, the monkey skimmed across the tree-tops and roof-tops of the city, to the white house at the edge of the maidan,

where a substantial meal could usually be negotiated without too much trouble. The house, the top of its walls beginning to

glow a rich pink, was silent, and the laundry line was bare. The monkey wandered disconsolately across the roof, pausing to

sniff at the crumpled remnants of a kite. He squatted at the edge of the roof, above the court-yard, feeling faintly, tantalizingly,

the lingering odours of cooking float up from the kitchen. Restless, he moves, and is momentarily silhouetted against the

pink-white wall where the staircase emerges onto the roof, and then, abruptly, a thin line of white light blossoms from a

dark window, and the monkey feels an impact against his chest, under his right shoulder, an instant before he hears the flat

WHAP, before he registers, with a baring of fangs and an amazed growl, that something very bad has happened; he feels himself

being spun around, sees suddenly the red sun, the pink-white wall splattered with red; the world spins and breaks into fragments,

red and white, red and white, another wall a glowing yellow, staggering to the side, the edge, slipping and stumbling, a slow

slide, a desperate grab at the edge of the roof, but already strength and balance are gone, and the monkey drops, turning,

and in the drop, within the space of that turn, a wholly unfamiliar image, a completely un-monkey-like scene flashes into

its mind, red and white, red and white, glowing yellow, three thousand lances, the thunder of hooves, and then the monkey

hits the red brick with a thick thump, to lie silently at the edge of the court-yard.

Abhay walked out to the still lump of flesh and fur, carrying the rifle, and stood over it, staring down, blinking, at the

neat round hole drilled into the fur, just beginning to fill with blood. A moment later, his parents burst out of the dark

recesses of the house, rubbing their eyes.

‘Abhay, what have you done?’ Mrs Misra said.

‘Abhay, you know there is a Hanuman temple not five minutes from here; if they find out they’ll start a riot!’

‘Is it still alive?’

‘Yes, I think so; help me get it inside.’

Abhay watched, his pulse suddenly vibrating and strumming hoarsely in his ears, as his parents picked up the limp animal and

carried it into his father’s study. His mother came out, then hurried back past him, carrying a pot of steaming water, her

eyes reproachfully averted, but he stood, paralysed, the stock of the rifle hard and heavy in his hand, staring with unbelieving,

stunned eyes at the stains on the ground, red on red.

For nine days and nine nights the monkey lay unconscious, its chest swathed in cotton, eyes closed, while Mrs Misra held handkerchiefs

soaked in milk to its lips, and Mr Misra paced up and down, hands clasped behind his back. The door to the room was kept closed

to prevent visitors from catching a glimpse of the wounded monkey, but often Abhay stood outside the room, a puzzled look

on his face, moving his head back and forth. On the ninth day the monkey opened his eyes and gazed uncomprehendingly at the

ceiling. The Misras recoiled, a little frightened, but the monkey didn’t seem to notice them. It lay, eyes glazed, lost in

an internal fog in which pieces of a life long gone drifted together, images colliding and melding to form a self, a ragged,

patchwork nothing, a dream, a person named Parasher. I know. I am he. I. I am the monkey. I am that diaphanous mechanism once

encased in human flesh and known as Parasher, or Sanjay. I am he, come back from the phantasmagorical regions of death and

the mists of animal unknowing.

I felt my soul settling into a shape, a form. Each day I remembered more, and each day I grew more conscious. At first, as

I lay paralysed, I could barely see the man and woman who kept me alive. When my sight cleared, I saw that they were dressed

in garb I could not put a name to but which seemed strangely familiar. There was a look of wariness on their faces that I

could not quite understand, and I strained my throat to tell them that I was Sanjay, born of a good Brahmin family. I could,

however, emit only sudden growls from the back of my throat, which caused them to retreat in fear. Then, you see, in my delirium

and shock, I imagined I was still swathed in the human body I knew so well, with its two scars on the forehead, its flowing

white hair and the missing finger on the left hand. So, I lay limp, seeing pictures coalesce in the motes of dust above my

head, and I saw a face appear again and again, a

broad, kindly face with sad eyes and a resolute jaw, greying whiskers, oh, my Sikander, those sad, sad eyes —I saw this and

other things, tumbled together and indistinct. On the sixteenth day I found I could move my left arm. Slowly, straining, I

raised my hand away from the soft cloth it had been resting on; slowly, my heart pounding —I believe I knew before I ever

saw the fur and the brown-yellow flesh —I brought it up, closer to my immobile head until I could see it, and then my blood

ran cold. In that instant, I remembered the last awful moments, I remembered my death, that terrible walk through the rain,

and the dark figure that walked beside me. In that instant I knew what I had done and what had happened, what I had become.

I brought the hand close to my eyes and looked at it, noting, in a wildly detached manner, the cracked skin of the palms,

the matted fur and the small black fingernails. I ran my hand over the contours of my face, feeling the fur along the cheek-bones

and the jutting jaw, the quickly receding forehead and the jagged teeth. Gathering all my strength, I raised my head and glanced

around the room, seeing first a little ivory statuette on a table, a delicately sculptured chariot drawn by six horses, bearing

a warrior and a driver under the banner of Hanuman, and seeing that familiar image I was momentarily relieved, but then I

saw the rest of the room, the shelves brimming with books and the strange white sheen of the impossibly fast punkah that rotated

overhead, the equally strange pictures on the wall, and I knew then that I was immeasurably far from home. Terrified, I tried

to get up, scrabbling weakly at the sheets, whimpering. Somehow, I managed to turn my body; I felt myself drop and hit a hard,

cool floor. Dimly, I sensed hands picking me up. My vision constricted, and I hurtled down a long, dark tunnel, and then,

once again —darkness.

As my body regained its strength, I slipped increasingly into a hazy narcosis induced by fear, by the terror of the unfamiliar

and unknown. Unable to speak to my benefactors, to produce the sounds of Hindi or English with my monkey-throat, I sat huddled

in a little ball, paralysed, listening to the strange inflections in their language and the wonderful and incomprehensible

things they spoke about. Consider, if you will, the hideousness of my situation. To be sure, I had once professed to despise

the condition of being human, and had longed for a life

confined simply and safely to the senses, but to be trapped in a furry, now-unknown body, fully self-conscious and aware yet

unable to speak and unwilling to communicate for fear of causing terror —this is a terrible fate. To construct an elaborate

simile in the manner of the ancients, my soul prowled about restlessly like a tiger caught between a forest fire and a raging

river; I was now immeasurably grateful for the gift of self-awareness but was terrified of the trials and revelations that

would undoubtedly follow in this strange new world. For a while, at least, I was content to sit in a corner and watch and

listen. I learned, soon enough, that the woman’s name was Mrinalini. With her greying hair, quick laughter, round face and

effortless grace she reminded me of my mother. He, Ashok Misra, was tall, heavily-built, balding, gentle, with a wide, slow

smile and a rolling gait. From their conversations I gathered that they had both been teachers, and now lived in retirement,

in what passed for vanprastha-ashrama in this day and age, more or less free from the everyday tasks and mundane worries of

the world. Apart from the natural respect one feels for gurus, for those who teach, I soon conceived a liking for this amicable,

gentle pair. Even for one such as I, it is comforting to see people who have grown old in each other’s company, who enjoy

and depend on one another after long years of companionship. Perhaps, despite myself, I communicated some of this feeling

to them, in the way I sat or the way I looked at them, for they grew less fearful of me. Soon, each of them thought nothing

of being alone in the room with me, and went about their business as usual, regarding me, I suppose, as a sort of household

pet.

On the twenty-ninth day, Ashok sat before his desk and pulled the cover off a peculiar black machine, which I was to later

realize was a typewriter. Then, however, I watched curiously from a corner as he fed paper into it and proceeded to let his

fingers fly over the keys, like a musician playing some strange species of instrument related vaguely to the tabla: Thik-thik,

thik-thik, and the paper rolled up and curled over, revealing to me, even at that distance, a series of letters from the language

I had paid so much to master. Intrigued, I lowered myself to the ground and walked over to the machine, causing Ashok to jump

up from his chair and back away. Fascinated, I hopped up onto the table and circled the black machine, running my fingers

over the keys with their embossed, golden letters. I touched a key lightly and waited expectantly.

Nothing happened, and I tried again. Smiling, Ashok edged closer and reached out with his right hand, index finger rigid,

and stabbed at a key, and an i appeared on the paper. Without thinking, delighted by this strange toy, I pressed a key and an a magically appeared next to the i; intoxicated, I let my fingers dance over the keys, watching the following hieroglyphic

manifest itself on the sheet: ‘iamparasher.’ Ashok watched this exhibition with growing uneasiness; clearly, my actions were

too deliberate for a monkey. I learned much too fast. Bending over, he peered at the sheet of paper. Meanwhile, I was engaged

in a frenzied search for the secret of spaces between letters, pressing keys and rocking back and forth in excitement. Finally,

I sat back and tried to remember the manner of the movements of Ashok’s hands over the keys. I looked up at him, and motioned

at the machine, gesturing at him to type something again. He grew pale, but I was too excited to stop now. He leaned forward,

and typed: ‘What are you?’ I hesitated now, but I had already stepped into the dangerous swirling waters of human intercourse,

tempted once again by a certain kind of knowledge and the thrill of the unknown. There was no turning back. I leaned forward.

‘i am parasher.’

When Ashok, his face pale, ran out of the room, I slumped to the hard wooden surface of the desk, suddenly exhausted. Drawing

my knees up to my chest, I let my mind drift, filled with an aching nostalgia and afraid of what I would discover in the next

few minutes, afraid of the bewildering depredations and convolutions that are the children of Kala, of Time. I let my mind

fix itself on one image, and clung to it —red and white, red and white, three thousand pennants flutter at the ends of bamboo

lances with twinkling, razor-sharp steel heads; the creaking of leather, the thunder of hooves; three thousand impossibly

proud men dressed in yellow, the colour of renunciation and death; the earth throws up dust to salute their passing, and in

front of them, dressed in the chain mail of a Rajput, the one they called ‘Sikander,’ after the rendered-into-story memory

of a maniacal Greek who wandered the breadth of continents with his armies, looking for some unspeakable dream in the blood

and mire of a thousand battle-fields; even the images we cling to give birth to other stories, there are only histories that

generate other histories, and I am simultaneously seduced by

and terrified by these multiplicities; I worship these thirty-three million three hundred and thirty-three thousand and three

hundred and thirty-three gods, but I curse them for the abundance of their dance; I am forced to make sense out of this elaborate

richness, and I revel in it but long for the animal simplicities of life pointed securely in one direction and uncomplicated

by the past, but it is already too late, for Mrinalini and Ashok and a dark, thin face I seem to remember hover over me, filled

with apprehension and awe and fear.

‘Who are you, Parasher?’

I pushed myself up, and typed:

‘who is he’

‘My son, Abhay. But who are you?’

Abhay’s eyes were filled with a terror I have seen before —it is the fear of madness, of insanity made palpable, of impossible

events, the existence of which threaten to crack one’s mind in two like a rotten pomegranate. He was very close to breaking,

walking around me, rubbing his head. I hurriedly typed:

‘do not fear me. i am sanjay, born of a good brahmin family. i delivered myself to yama in the year nineteen hundred and eleven,

or, in the english way, eighteen hundred and eighty-nine after Christ. for the bad karma i accumulated during that life, no

doubt, i have been reborn in this guise, and was awakened by the injury i suffered. i wish you no harm. i am very tired. i

am no evil spirit. please help me to the bed.’

I lay exhausted on the bed, unable to shut my eyes, fascinated, you see, by the thought of the world that lay beyond the house.

I gestured at Ashok to bring me the machine; as soon as it was set beside me on the white sheets I typed feverishly:

‘where am i. what is this world. what year is this.’

The rest of the afternoon, as you may imagine, passed quickly as Ashok and Mrinalini, in hushed tones, told me of the wonders

of this time, filling me with dread and amazement as they painted a picture of a world overflowing with the delights of a

heaven and the terrors of a hell. Abhay listened silently, tensely watching his parents speak to an animal; he frequently

looked away and around the room, as if to locate himself within a suddenly hostile universe. Finally, shadows stretched across

the brick outside, and I lay stunned, my mind refusing to comprehend any more, refusing, now, to understand the very words

that

they spoke; drained, I was about to tell them to stop when a thin, piping voice interrupted:

‘Misra Uncleji, my kite-string broke and my kite is stuck on the peepul tree and could you…’

The speaker, a girl of about nine or ten, dressed in a loose white kurta and black salwars, stepped through the doorway and

stopped short, her face breaking into a delighted smile.

‘A monkey! Is he yours, Abhay Bhai?’

‘No,’ snapped Abhay. ‘He’s not mine.’

‘Come on, Saira,’ Ashok said, trying to divert her, but Saira’s interest had been aroused, and she was clearly a very intelligent

girl with a very determined mien. Side-stepping Ashok, she stepped up to the bed, alert eyes instantly taking in the typewriter

and the bandages.

‘Is he hurt? I…’

She stopped suddenly, but I was unwillingly fascinated by the ball of kite-string she carried in her left hand. I reached

out and touched the dangling, ragged end of the string; it dawned upon me gradually that a blanket of silence had descended

upon the house —I could no longer hear the chirping of birds or the distant, hollow sound of cricket balls being struck; I

let my eyes wander from the string and noticed, vaguely, the goose-bumps on Saira’s forearm; I looked up at the doorway and

knew then, stomach convulsing, knew, for the air outside had turned a deep blue with swirling currents of black, knew, for

I felt my chest explode in pain, knew, for out of the densening air a huge green figure coalesced to stand in the doorway,

knew then that Yama had come for me again. Yama, with the green skin and the jet-black hair, with the unmoving flashing dark

eyes and the curling moustache, he of the invincible stre

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...