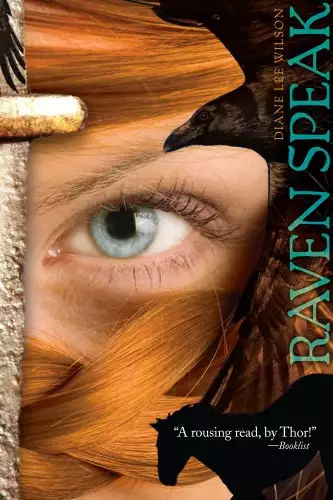

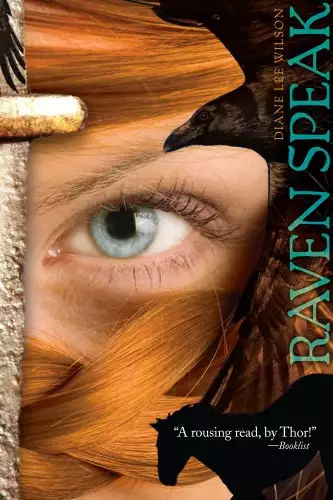

Raven Speak

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Asa is the daughter of a Viking chief whose clan is struggling to survive a never-ending winter. All the able-bodied men head to sea in search of food, leaving behind the children, the elderly, the sick—and Jorgen the skald, the wise man who will stop at nothing to take over the clan. When Asa learns the skald wants to kill and eat her beloved horse, she runs away—but soon realizes she has to return and try to save her mother and clan. And when she meets a strange woman with one good eye, who talks to her two ravens, Asa’s adventures really begin….

Release date: April 26, 2011

Publisher: Margaret K. McElderry Books

Print pages: 256

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Raven Speak

Diane Lee Wilson

In the pale light of a wintry morning seven men saddled their ship across bucking white waves. A girl stood alone on the shore. Stiff and silent, with her fingers clenched into fists and her eyes creased into flashing slivers of blue ice, she watched them go. The others of her clan, those that still lived at least, had long since shouted their fare-you-wells. But they’d left their crumbs of hope at the ocean’s edge to shuffle back to the village, slump-shouldered and spiritless. The girl remained, staring rigidly at the horizon.

As dawn edged across the ponderous gray sky, the ship grew smaller and smaller. Its struggling flight was measured by the ocean’s slow, rhythmic breath, a sucking inhale followed by a rushing exhale that darkened the shore. Spray misted the girl’s face and beaded her brow. The anger bubbling inside her vibrated the glistening beads, and some shook loose to trace the bridge of her nose while others skated down her temple and crossed her hollow cheek. The trickling water surprised her and then, just as quickly, shamed her. Don’t you cry, she scolded. Don’t you dare cry. And to make certain she obeyed, she dug her nails into the flesh of both palms.

When the fogged horizon finally swallowed the ship, taking her father from her silently and completely, the vast ocean seemed to swell with a vicious pride. She kicked at a speckled stone. It stuck to the wet sand, cold and obstinate. Angrily she snatched it up and hurled it into the surf. Its noiseless scuttling did nothing to assuage her. So she threw another stone, and then another and another, heaving with all her strength and grunting like an animal until the dun horse behind her nickered his worry. That finally spun her round. Gathering up the reins, she threaded her fingers through his thick mane and flung herself across his back. She loosed her fury by drumming on his sides, and like the spark off a strike-a-light, he bolted. A sheet of airborne sand spattered the froth behind them.

Along the entire length of this westward-facing shore, black-green mountains plunged their ridged fingers deep into the sea. The clan’s village was nestled beside a fjord that separated one mountainous thumb from a mountainous forefinger, but the girl and her horse galloped hard in the opposite direction. Across the narrow ribbon of sand they flew, soaring over splintered driftwood and dodging ropy mounds of rockweed. Like the dragon-prowed ship they danced through the churning surf, leaping and twisting and flinging themselves at their own horizon. All the way around the long first finger they galloped, past the fishing huts and ribbed boats humped in rows like so many sun-drunk seals, and then the fat middle finger, where a whale had beached itself two summers ago and closed its glassy brown eyes for the last time and now there wasn’t even a bone left in remembrance, and on toward the neighboring finger. There she spied the silhouette of the ancient picture-stone with its weathered, mysterious carvings that she’d once paused to examine. But not today. When they’d rounded that tip of land and reached the shadowed fjord splitting it from the next, the girl realized how very far they’d gone—farther than they’d ever gone—and she fought the horse to a walk.

In wind-whipped defiance he shook his head. Trumpeting a blast of air that ricocheted noisily up the fjord, he let out a weak buck. Wondrous, really. In the barren days of this unending winter, when he was no more than dandelion fuzz on a skeleton, he bucked. That, at last, brought a smile to the girl’s face, and she laid a chapped hand on his thin neck.

Rune. The horse she’d known all her fourteen winters, the one she’d learned to ride even before she’d learned to walk. Aged now, but still her daily companion and most loyal friend. The cold air spun his breath into dragon smoke that swirled around his hairy ears, but Rune didn’t seem to mind; his head was up, eager. He’d been born to the cold.

Dropping the reins, the girl pulled first one foot and then the other up to the horse’s withers, trying to rub some feeling back into her toes. Would this cruel winter never end? It was nearly Cuckoo Month now, and bitter winds still scoured a beach empty of life. She let her legs go slack, scratched the roots of Rune’s mane, and sighed, but she didn’t shiver. She’d never shiver. She’d been born to the cold too.

From her very first day, when she’d been ceremonially laid on a nest of fresh reeds at her father’s feet, she had not cried; in fact, she’d not even shivered. How many times had he told her the story? All twenty-some members of their clan had gathered around the stone-ringed hearth after the night meal to watch him decide if she was worthy. As chieftain he could grant her life, assign her a name, and offer the clan’s protection. Just as easily he could wave her away, and then the skald would have carried her out to the rocks at the ocean’s edge and abandoned her to the biting winds and the hungry gulls.

“You never cried,” he always began his retellings. “Both of your brothers mewled like orphaned lambs, but not you. You didn’t cry, you didn’t shiver, and you didn’t even blink,” he said, warming up to his part in the story. “You latched your round blue eyes onto me and stared so seriously, so boldly, that at first I didn’t know what to do. Just ask your mother. So I scratched my ear, like this.” And here he paused to dig a finger into his left ear. “And I looked at my ring, like this.” He extended a hand to examine the engraved silver band. “And all the while you just went on staring at me like Jorgen the skald when he hungers for another piece of amber to carve his magic. I knew right then and there that you were no ordinary child, and I lifted you onto my knee. ‘This is no ordinary child,’ I said, and I cradled you in one arm like this,” and here he always crooked his arm and looked down at his empty elbow, “and I sprinkled water from the fjord onto your round bare belly. ‘She is to be called Asa Copperhair,’ I pronounced, for from the beginning you wore a crown of gold-red hair that rivaled the firelight. And I gave you your first gift: a copper spoon.”

That had been somewhere near midwinter in the year 854. And her father had been right: She was not an ordinary child—her name had lasted only three more winters. The girl, whom her mother had to drag by the wrist to help shell peas or knead dough or smooth clothes on the whalebone board, always managed to slip away the minute heads were turned. If someone took the time to chase after her, she could be found in the outfields picking small fistfuls of grass for Rune and the other grazing horses, or leading them to the mountain stream, or generally fussing over them until nightfall when, all by herself, she herded them into the byre with wildly flapping arms and a small shrill voice. If she didn’t appear beside the hearth for the night meal, she knew someone would be sent out to the byre to unclench her fist from Rune’s mane and lift her sleeping body out of the reed bedding. “So by the time you were four,” her father went on, “I had to admit my mistake—which, as you know, is not an easy thing for me to do—and I had to gather everyone for another naming ceremony. Again I sprinkled the cold water from the fjord onto you, only this time I dribbled it on your head.” He held his hand above her and mimed sprinkling water onto it. “And that time I got it right. ‘She is to be called Asa Coppermane,’ I said.” And he’d given her a horse-headed comb carved from antler.

The two prizes, the spoon and the comb, still dangled from the chain fastening her brown woolen cloak, and she fingered them, remembering. As the fog receded she looked out to the ocean horizon again. The ship was indeed gone. Stung with regret, she shouted the blessing she’d withheld all morning: “Fare you well!” But the wind whipped the words back to shore and she knew her father would never hear them.

Her call elicited an annoyed gronk above her head, and she looked up to see a raven lifting off the cliff face. It had been picking through a last year’s fulmar’s nest and the sight made her stomach growl. How well she remembered snatching up newly laid eggs one after the other and sucking them down so fast that the sun-yellow yolks dribbled down her chin. Her mouth watered. For months now there had been only tasteless onion soup and crumbly flatbread stretched too far with dried peas and pine bark. Needles poked her stomach constantly. Would this winter never end?

While Rune nibbled at the gluey remains of something washed onto the shore, Asa followed the raven’s flight. It circled overhead at first, eyeing her warily and gronking intermittently, then tipped its wings and flapped away. The cliffs flanking the fjord were so tall that the inlet’s neck was cloaked in darkness. This would be the end of their ride.

She was just turning away when a movement caught her eye. Along the opposite cliff face farther up the fjord stood a figure with an arm outstretched, and the raven, as if summoned, spiraled downward to alight upon it.

In the moments that followed, time seemed to slow, and while Asa’s heart thumped steadily, her breath caught in her throat. They were watching her, the person and the raven both; she felt certain of it. She sat motionless on Rune, apprehension dragging a finger along her spine. But then the bird was drawn close and both figures melted into the dusk.

Odd. She’d never heard anyone in her clan speak of another settlement in the area. The next village was far to the south. Curious, she urged Rune forward a few steps, craned her neck, and squinted, but the pair had definitely vanished. Odd.

The ocean rumbled as a large set of waves rushed the shore. A freshening wind whipped peaks of white from the choppy waters, in turn cold gray and bronzy green, and she looked to the sky with new worry. The pale light was rapidly withdrawing, fleeing from low-hanging clouds that glowered with menace. Images of hurled stones sinking beneath the waves mingled with the last sight of her father’s ship; no bigger than a stone it had seemed then, and she welled up with anger for those that had pushed him to such a foolhardy venture. It was the whispering that had done it, whispering that stirred doubts and suspicions, and the clan had listened with their bellies instead of their minds. Now, she feared, they’d suffer all the more. Gathering the reins, she looked again at the empty bird’s nest, just a fringe of dried grass shivering in the breeze. If only summer would hurry.

© 2010 Diane Lee Wilson

TVEIR

Frost still rimed the wood planks of the byre door as Asa looped her fingers into the knothole. She threw her weight back in a succession of short jerks and it gradually came open, its cold hinges shrieking complaint.

A sour odor wrinkled her nose as she led Rune down the earthen ramp and into the dark, windowless shelter. None of the animals there greeted them; the cow merely flicked an ear, while her father’s two horses swung their heads round for just a moment’s dull gaze. Such a difference in a matter of months.

At summer’s end, as was the custom, all of the clan’s livestock had been divided into the weak and the strong. The small or sickly animals were slaughtered before winter could take its toll, and the healthy—three cows, five pigs, and twelve sheep, along with the horses—had been locked inside the byre. There’d been at least some hay waiting for them then, along with carefully doled out rations of oats and barley. But the food hadn’t lasted, while the winter had.

One by one the remaining animals were slaughtered to feed the clan. It was a blessing almost, since they’d gone bony and shivering and in their final days their black eyes begged for relief. These starving animals could only dream of such a fate.

She pulled a length of brown rockweed from Rune’s shoulders and dropped it in front of the cow. The animal blinked and nosed the slimy strand with disinterest. She’d been spared all this time because she was pregnant, a seed of hope for the future. But the distended belly lolling over her folded legs seemed an absurdity, a bloated fungal growth sucking the life from its skeletal host.

The pigs were gone, along with their tasty chops and trotters, and the sheep, too, so there would be fewer woolen clothes for the clan this year. Already Asa’s underskirt stopped well short of her ankles, and the tears across each knee had been clumsily sewn shut. Her overskirt hid these imperfections, though, and her cloak was well made. Sitting around the hearth fire at night, she could ball herself up inside it and nearly keep warm.

At the sight of the rockweed, the other two horses pricked their ears and nickered. Asa pulled another glistening strand off Rune and dragged it over in front of them. They dropped their heads in unison to examine the offering.

As always, she ran her fingers along the side of each horse, feeling for herself their deteriorating condition. Their thin, shaggy coats were so dry and bristly, so starved for nourishment. Beneath her fingers the horses’ ribs pushed outward like barrel hoops. Her father had promised to bring grain if he found another clan with enough to share; otherwise the three animals, and Rune, would have to continue making do with the seaweeds she managed to scrounge from the shore or the inner bark she stripped from the pine trees. Her nails were shredded to the quick with that effort, and reddish resin mottled both hands. She didn’t mind this as much as the very act of yanking the skin off trees and eating it. That made her feel desperate, no more than an animal. Indeed, every person in her clan was now sunk to being an animal, to scraping out a meager existence while waiting—hoping—to emerge from hibernation.

Although Rune was the smallest, he did the most work carrying her out and back through the icy weather, and so she removed his bridle and fed him the last whole length of rockweed. After a final pat on the neck, she checked the water level in the barrel braced in the corner. Unable to see anything in the gloom, she reached in. An icy skim sucked her fingertips to its surface, and she had to yank them free before using a nearby stick to stab the ice into floating chunks. Grabbing a pail, she slipped out the door and climbed the steep path to the stream that tumbled from the mountains. As always, she looked for signs of anything new, anything green and uncurling, anything to show that summer was on the way and that the land would once again nourish them. But the rocks were mostly bare, and as she climbed she felt she was the only living thing in all that bleak world: A silent forest cloaked the mountains rising above her; an endless, empty ocean stretched behind her; and an ominous gray sky, heavy with clouds, clamped down on the fjord like a shield of ice. What could raise its pale head here and sing of summer?

It was on her way back down the path that she finally noticed something different. The byre door was open, and a somewhat misshapen person was wedged into its gap: Jorgen the skald. He was the clan’s storyteller, poet, and occasional prophet—a man she detested. And he was looking at the animals. Mindful of the slippery pebbles, she nonetheless quickened her steps. The splashing water cleared the pail’s rim.

He heard her coming and spun. “What are you doing?” As if he couldn’t see the pail for himself.

“Fetching water.” She took a bold step forward, but he blocked the doorway with his twisted, turdlike body. Baths had occurred infrequently the last few months, but the skald had a peculiar odor that went beyond not bathing. It turned her stomach.

“You’ve not been fetching water all this time. Where did you disappear to after the ship’s leave-taking? Your mother’s been waiting for your report and you’ve worried her beyond any of my help.”

If that was meant to hurt, it worked: His accusation drenched her with guilt. Her mother had been too ill that morning to walk to the shore to see off her husband and the other men. Yet Asa hadn’t returned directly to her. Dwelling on her own worries, she’d gone galloping. “I went for a ride,” she answered, and hastily added, “looking for food.” Squeezing past him, she nodded toward the slimy weeds mouthed by the animals. His stench clung to her like a resinous film. Slowly, hoping he would leave, she rested the pail on the edge of the barrel and took her time pouring out the fresh water. But when the last drop had trickled into the barrel, she turned to find him studying the horses with the toothy greed of a wolf.

Her father, the clan’s chieftain, had decreed that the remaining animals were not to be slaughtered. The pregnant cow was their only chance at milk and cheese and a future herd. And while eating horses was not out of the ordinary, these were her father’s pride, a luxury he allowed himself. The red stallion was his and the bay had been a gift to her older brother. Rune had been intended for her other brother, but the impish creature had bucked him off with such abandon that for years Rune had worn a harness in the fields rather than a saddle on his back. Less than two years after Asa had been born, however, she’d discovered the horse dozing on the ground and clambered onto his back. They’d been inseparable ever since. She wasn’t going to let anyone kill and eat him.

With that resolve in mind, she set her jaw and, giving the skald her iciest glare, moved past him. Claiming an authority that went beyond her fourteen years, she stood outside the byre door and waited for him to remove himself. Again she held her breath as he brushed past. What made him smell that way? Rotten onions? A bleeding tooth? Pee? She recoiled as he turned back and, still grinning, stepped right up beside her to help her shoulder the byre door closed. One behind the other then, heads bent, they hurried toward the longhouse. A stray, bitter wind raced up the fjord to snap at their heels.

Upon the stone door-slab, the skald hesitated and glanced back at the byre.

“The spruce trees are beginning to bud, I think,” Asa said, hoping to prove that summer was coming, that wild cress and leeks would soon be in their future and in their stomachs. That they’d survive without having to eat the horses. “And I saw a fulmar’s nest.” Essentially true.

He looked down at her and grinned, showing wicked yellow teeth. “Did you now?” he said on a rush of noxious air. The odor fogged the entry until he turned and went into the longhouse. He scanned the room to see who was watching, then took his place beside the fire and sat, rocking.

The longhouse was as gloomy as the byre and nearly as cold. What had once been a snug shelter dancing with firelight and vibrating with people’s laughter was now a sooty, smoke-filled hall. Peevish words were flung like gravel; lengthy silences hung in the air. The reeds covering the earthen floor had long been ground to dust. The soapstone dishes had run dry of whale blubber, so there was no light except for that coming from the fire glowing in the central hearth. In the early months of winter the iron cauldron suspended over the hearth had held rich brown stews of beef or mutton. Now, day after day, it kept a watery soup simmering beneath a gray foam. The flavor changed from bitter to greasy to burnt depending on what mushy vegetable was scrounged from the storeroom or what bony rodent was trapped, pounded to a paste, and stirred into it.

Asa hurried over to where her mother lay on a straw mattress pulled close to the fire. As wife of the chieftain, she’d be in charge of the clan until the men returned. So she’d left her private bed-closet at the south end of the longhouse and set up command by the fire’s meager warmth. Secretly Asa wondered if it was all a mistake. Her mother, wrapped in a feather quilt overlaid with two sheepskins, could barely lift her head. How was she going to lead a restless clan?

As if sensing her worries, her mother reached out an arm to caress her daughter’s cheek. “How is Rune today?”

Nothing about her husband leaving, nothing about every one of the able-bodied men leaving in a desperate venture to provide food. No, her mother would set aside her own worries to be a leader, strong in the face of the disaster that was engulfing them. “I found some rockweed for him and the others,” Asa responded, “though we had to ride a long way. But when I carried water from the stream it looked like some of the spruce trees were beginning to bud. There were purple knobs on the ends of the branches.”

With a weak smile, her mother tucked her arm back under her feather quilt and closed her eyes. “Tell me about your ride. What did you see?”

That was her way of asking for a story. In the monotonous, housebound months of winter, even insignificant events had to be told and retold, with ever more interesting details embroidered onto them, to help pass the time.

Asa recounted her ride around each finger of the mountain range, describing the ocean’s changing colors, the ancient picture-stone that sprouted from the whale-nosed bluff, the weighty shapes of clouds in the sky, and ending with the raven and the strange figure. “I saw it land on a man’s arm, but I didn’t see a village anywhere. Does Father know about the people living there? Maybe they have food.”

Her mother spoke with her eyes still closed. “I’ve never heard him speak of another village nearer than a day’s sail away. Are you sure of what you saw?”

She thought. The fjord had been very shadowy, but yes, she’d seen the raven alight upon something that had to have been a person. She nodded. “Yes, I’m sure.”

That brought her mother’s eyes open. “Did he look evil—a raider or a pirate? Did you see his ship?” She lifted onto one elbow. “With the men gone we’re easily taken. I’ll have to do something, prepare… . I wonder if they saw your father and the others leave.”

Ill as she was, her mother didn’t need more worries. “Maybe it was just my imagination,” Asa soothed. “The fjord was in shadow, and when the raven swooped into the shadows it looked like he landed on the arm of a person, but it was probably just a tree.”

“You’re sure?”

Her mother’s eyes begged the answer, and so she gave it. “Yes,” she replied, “I’m sure we don’t have to worry about raiders.”

And that, in essence, was also true. Why should they worry about raiders when they had nothing to be raided? The brutal weather had already stripped them of everything.

The months of late summer and early winter had been the harshest anyone could remember. Rain had fallen in torrents and the crops had become moldy. Then, almost without pause, the rain turned to hail and flattened the blackened stalks. What hay that could be salvaged from the mold was put up in the byre, but it was only a third of what was needed. Cabbages were stunted, pea pods mostly empty. The deer and elk climbed into the shelter of the high mountain forests, and even the gulls seemed to have flown to more temperate shores. In hard times the ocean had always provided plenty of food, but when the storms finally ceased, the fish, too, had apparently swum away, because time after time the nets were drawn in empty.

Needles pricked everyone’s stomachs unendingly, and still the winter stretched on. Then, in the darkest days, an awful sickness had begun clawing its way through the clan. The room divided into those who turned their feverish faces toward the cold drafts whistling through the cracks and those who huddled beside the fire, unable to melt the frost that gripped their marrows. Hour after hour, day upon day passed when the clan’s members sat in the dark, too ill to move, chewing on bark or vomiting it up. Movement ceased, and an entire day could go by before anyone noticed that a hand no longer twitched or that eyes stared unblinkingly at the rafters. No one was strong enough to dig a burial chamber; it was all anyone could manage to just roll the stiff body in a length of cloth, lay it on a plank, and carry it out to the smaller byre, the empty one, to wait in a frozen row with the others. Nine so far. Two of the shrouded bundles held Asa’s brothers.

Was it the deaths of his sons that had driven her father out into a wintry ocean? Or the grumblings? She’d watched as he’d tried desperately to bolster the clan’s spirits with enthusiastic plans for the coming summer: A new field would be cleared for more hay, a separate cooking house would be built for easier food preparation. Everything would improve. He openly complimented the women on their weavings and urged them to continue. He lapped up the soup that was served to him and pronounced it delicious even though everyone, including herself, could look into their bowls and see it was nothing but dregs.

But his smiles and optimism weren’t enough. The cuckoo didn’t come; the rains didn’t cease; and the wool gave out. And hands couldn’t weave hope out of nothing. The grumblings began that this was the chieftain’s fault. He hadn’t done enough—wasn’t doing enough—to feed his clan.

So, thinner and sad-looking at last, he’d taken what few men were well enough and set out under stormy skies to find food or better land or possibly another friendly clan that had foodstuffs to share, though Thor knew they had little to trade. That left behind four women and five children, along with old Ketil, whose broken leg hadn’t healed properly after his timber accident, and Jorgen the skald. Asa suspected he’d had a hand—and a tongue—in her father’s ill-timed departure. While he’d always been kind to her, telling her stories and taking an interest in Rune and even carving a small likeness of him once as a gift, she seized every opportunity to escape him. There was something about him that made her skin prickle, something that wasn’t right. And as she took up the comb to stroke her mother’s hair, she warily studied the hunched man smiling to himself across the fire.

© 2010 Diane Lee Wilson

PRÍR

Jorgen held the smile on his face because she was looking at him and because it masked his real feelings. They were irritatingly strong feelings, feelings he couldn’t quite control, and so he made himself smile while he sat thinking. And listening, always listening. And rocking.

She didn’t fear him. That’s what annoyed him the most. The others, even her pigeon-chested father, the clan’s chieftain, could be made to move aside with a dark glance. It was a precious art, one he’d been polishing for many years now, and he wasn’t about to let some child—a girl, no less—shrug that away.

He felt for and found the bear tooth amulet he had tied on a thong around his waist and kept next to his skin, hidden beneath his tunic. His father, the clan’s skald before him, had given it to him, relating a belief about the amulet’s power. He chuckled, allowing his smile to widen a crease. Funny how his father hadn’t realized the heady power of his own position. For all the man’s wisdom he’d never noticed how easily people could be influenced by a carefully worded compliment or chastened by a pointed rebuke. But Jorgen had; he’d hung in the shadows and watched people, all the while waiting for his father to die. And while he was waiting, he’d come to know each weakness and each want—and discovered how one could feed the other—for every member of the clan.

When his father had finally died—a terrible accident, really, bleeding to death all alone in the forest following a mishap with his axe—Jorgen had taken his honored position at the hearth fire. He continued entertaining the clan with the stories of his father and his father before him, but he recrafted the stories here and there to fill the clan’s needs and to guide their desires. He told how great men rose up; how peoples came to be conquered; how the gods, in their pleasure, sought to aid humans—or in their anger, turned away from them.

Shaking his head, he released the amulet. They were like children, really, squatting with mouths agape, waiting to be spoon-fed the pabulum that was his stories. He’d nursed them well thes

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...