- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Dahin believes he has clues to the location of the Hierarchs' Well, and the Witch King Kai, along with his companions Ziede and Tahren, knowing there's something he isn't telling them, travel with him to the rebuilt university of Ancartre, which may be dangerously close to finding the Well itself.

Can Kai stop the rise of a new Hierarch?

And can he trust his companions to do what’s right?

Follow Kai to the end of the world in this thrilling sequel to the USA Today-bestselling Witch King.

Release date: October 7, 2025

Publisher: Tor Books

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

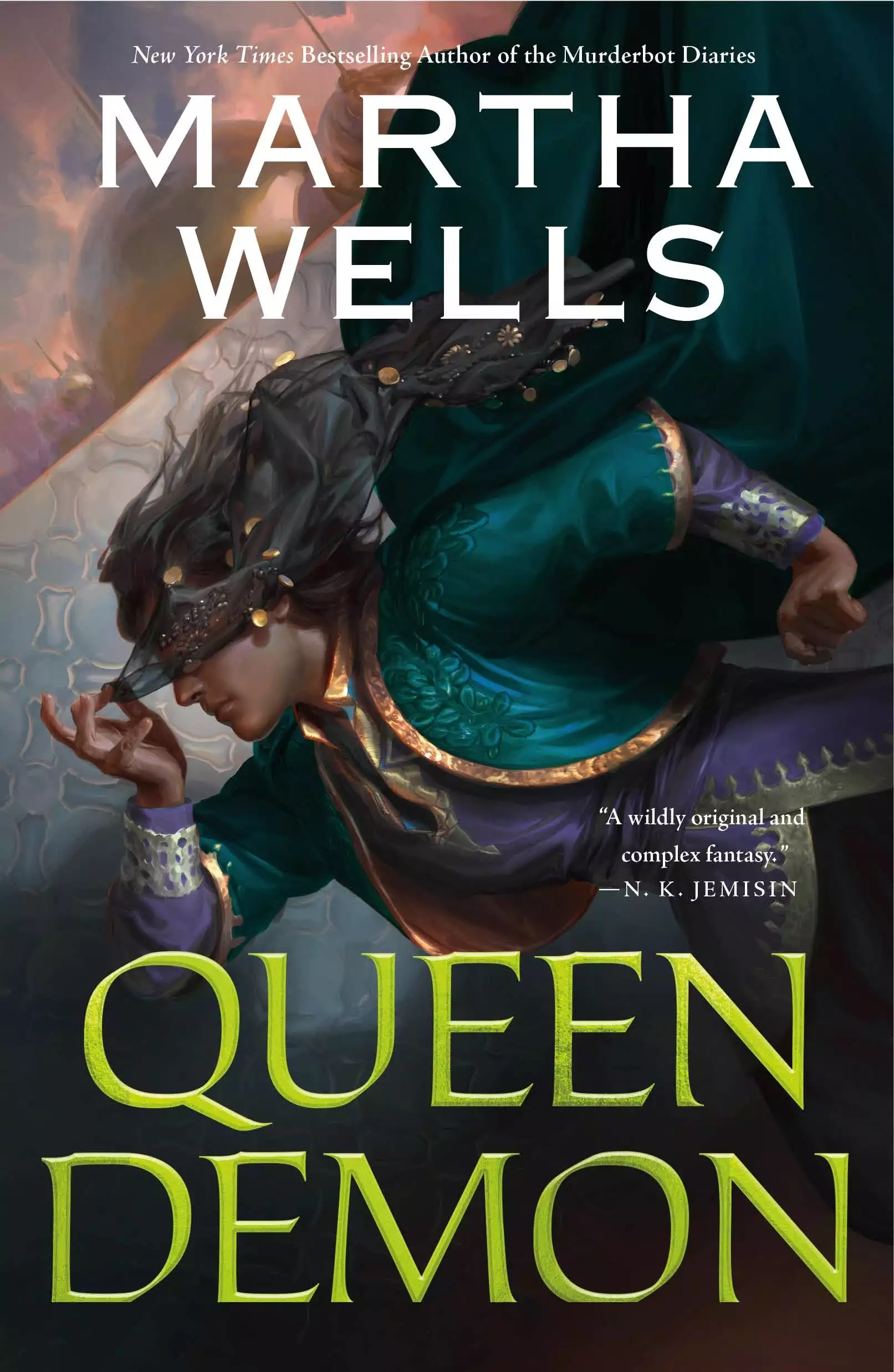

Queen Demon

Martha Wells

One

They had left the Kagala behind them, flying over the dry plain of the western Arik in an Immortal Blessed ascension raft. Kai curled on the bench with his back against the metal wall of the curtained shelter, facing into the warm wind, trying to ignore the argument. Which was impossible, considering which members of his extended family currently living in the mortal world were here.

Using her heart pearl to speak silently to him, Ziede said, Just don’t jump off the raft.

Too tired to even feel sour about it, Kai replied, I’m going to spend the next fifty years living in the Arkai marshes with Dahin.

The raft was shaped like a curled gingko leaf, and though it was large as such crafts went, there wasn’t much room to get away. Toward the bow, Saadrin and Tahren faced off. Both Immortal Marshalls, they resembled each other in their height and strong build, their features similar enough for a stranger to guess that they were related. Tahren’s hair was blond and a few finger widths long, and Saadrin’s was silver and cropped so close it was just fuzz on her scalp. Her light tawny-golden skin was darker than Tahren’s ivory. Both were missing their armor and their only weapons were scavenged from their mostly dead captors. Their bedraggled clothing had been washed in water drawn from the Kagala’s desert well but didn’t look much the better for it.

And of course Saadrin was a complete ass. With all the confidence of someone whose will was seldom questioned, she told Tahren, “You can’t shirk your responsibilities like a weak mortal.”

Deadpan and as immovable as a mountain, Tahren countered, “I can. And the mortals you call ‘weak’ often have more moral fortitude than the strongest Immortal Marshall.”

Dahin stood at the raft’s steering column, his gaze on the horizon as if lost in thought. A Lesser Blessed, he was small compared to the Immortal Marshalls, light hair tied back in a queue, wearing an equally battered Arike-style tunic and skirt. He said, “Kai wouldn’t let me stab Aunt Saadrin and now he regrets it, don’t you, Kai?”

Kai sighed. Tahren didn’t react, but she caught Kai’s gaze across the raft and her left eyelid twitched. Kai sympathized. Dahin hated other Blessed, especially the ones he was related to. Maybe I’ll live alone in the Arkai marshes, Kai thought.

Saadrin ignored Dahin except for an exasperated grimace. Still trying to glare Tahren into submission, she said, “Even you won’t ignore your role in this farce of a treaty and let the consequences fall on the Blessed, no matter how forsworn you are.”

“I might,” Tahren said, with no detectable sarcasm whatsoever. After a beat, she added, “I find myself more inclined to it with every passing moment.”

It was always strange how the Blessed would refer to Tahren as if she were something to be scraped off their boots when the rest of the Rising World considered her a hero and savior. Kai touched Ziede’s heart pearl and said, You and Tahren should come to the marshes with me.

That’s not helpful, Ziede Daiyahah replied. She stood beside Tahren, absently tapping her nails on her folded arms. She had wrapped her long dark braids up in a scarf, and her dark brown skin was without makeup, her long tunic and pants as bedraggled as the rest of their clothes. It made her look oddly bare and stripped down to essentials, ready for a battle. She added, Tahren is fucking furious.

Good, Kai told her. Tahren had every right to be fucking furious. When they had first rescued her from the Witch cell in the abandoned Kagala fortress, Tahren had assumed Ziede and Kai had been searching for her the entire time she was missing. The power written into the walls of the cell had left her in a waking dream, and she had no idea how long she had been imprisoned. Then Ziede explained that she and Kai had been captured at the same time, entombed, and had only recently escaped.

“You have to admit, Aunt Saadrin,” Dahin said conversationally, idly making a minute adjustment in the raft’s direction as the wind tried to shove it sideways. “The Blessed have certainly asked for any consequences they get. It’s rather a habit of the Blessed, asking for consequences and then whining once they get them, isn’t it?”

Saadrin’s jaw set. She didn’t look at Dahin, but her answer was clearly directed at him. Which was a mistake, Kai could have told her. She said, “It was not all the Blessed who did this. Only a few are foresworn.”

Dahin laughed. “Oh, Aunt Saadrin. Someone’s going to have to teach you about irony. Maybe it’ll be me.”

Tahren knew Dahin too well to respond to him when he was like this. Still focused on Saadrin, she said, “If only the Blessed did not have a history of blaming the many for the actions of the few.”

Kai snorted quietly in appreciation. Tahren knew how to hit Saadrin where it hurt. Not that it was helping anything.

The argument was about where they would go next, and who would go there. Kai and Ziede had assumed Saadrin would want to return to the Blessed Lands with her prisoner, the Lesser Blessed Vrenren. He was currently sitting on the floor of the raft, tied up with rope meant to restrain the Immortal Blessed, and watching the argument with wide eyes. As one of the few survivors of the Immortal Blessed faction of the conspiracy, he apparently had too much sense to contribute.

Kai thought Saadrin would have been eager to return to the Blessed Lands and report all the perfidy to the Patriarchs. Reporting on other people’s perfidy was one of the few things Saadrin seemed to truly enjoy, as far as Kai could tell. Instead she wanted to go directly to Benais-arik.

Benais-arik, where the real plot had been hatched.

They didn’t have to go with her. Dahin could take them to the nearest canal outpost where they could leave Saadrin to continue her journey with the raft while they made their way home to Avagantrum by boat. But Saadrin wanted Tahren to speak to the council at her side.

Saadrin’s whole face had tightened at Tahren’s last comment. Obviously trying to pretend it hadn’t hit home in the worst way, she said stiffly, “This is no joking matter.”

Tahren’s sense of humor was dry as dust but it was obvious she was deadly serious now. She said, “I am not known for joking. I am known for dispensing justice.”

“Justice except for what you owe to your own blood kin—”

“You are lucky I’ve spared you justice. If I gave you what you were owed—”

Ziede, Scourge of the Temple Halls, said aloud, “I’m unsuited for the role of peacemaker and if I’m forced into it, you will all regret it.” She added through her heart pearl, Kai, and you know how much it pains me to say this, Saadrin is right about going to Benais-arik. The Rising World council should see Tahren.

Kai grimaced. Tahren was a lynchpin of the relationship between the rest of the Rising World and the Immortal Blessed. The Arike, the Enalin, the Grale, the Ilveri, and all the other members would be much reassured to see her, and to hear her speak about the end of the conspiracy. Saadrin’s involvement in Tahren’s rescue would show that there were still Immortal Blessed who kept their word and upheld the treaty. The Immortal Marshalls who represented the Blessed Lands to the council would be indebted to Tahren and furious about it. Kai had to admit all that was true. He didn’t have to like it, but he had to admit it.

Saadrin twitched toward Ziede and started to speak, then took in the change of expression on Tahren’s face. The change of expression that said, be rude to my wife and I will end you. Saadrin clearly wasn’t afraid of Tahren but she must be all too aware what fighting her would be like. She changed whatever she had been about to say to, “You may all be more than ready to turn your backs on the Rising World, but the Blessed and the mortal lands—” She waved a hand toward Sanja and Tenes, sitting just inside the doorway of the little domed shelter behind Kai. Sanja watched avidly. Tenes frowned in concern. “—bear the consequences.”

Tahren’s gaze narrowed. She turned her head slightly. “Sister Tenes, young Sanja, what do you say, as representatives of the rest of the known world?”

Sanja’s expression was a mix of confusion and suspicion. She was small, barely old enough to be called an adolescent, with the brown skin and tightly curled dark hair common to most of the east. She didn’t know Tahren at all yet and nothing in her former life as a street child in the free city at the Mouth of the Sea of Flowers had inclined her to trust. She looked at Tenes for help.

Tenes was a Witch. She looked young, with light silky hair and lighter skin, and she might have been from anywhere to the south or west or north of the whole world. An expositor had taken her as a familiar and she had lost her memory and her voice to him. All Kai could tell of her past life was that she was probably from a borderlander witchline. She looked from Tahren to Saadrin and signed, I follow Kaiisteron.

“Me too,” Sanja added belligerently.

Tahren faced Saadrin again. “And me.”

Dahin waved a hand without turning around, currently guiding the raft through a particularly tricky vagary of the wind. “And me. You know, mostly. As much as I ever do anything.”

That was that. Kai uncoiled from the bench and stood. The wind pulled at his hair and his dusty tunic and skirt. He said, “Tahren, would you speak to the Rising World council if I ask it?”

“If you ask it, yes,” Tahren said without hesitation.

“I ask it. We’ll go to Benais-arik.”

“So we shall.” Tahren turned from Saadrin as if she had suddenly ceased to exist.

Saadrin folded her arms and looked away, and managed to keep the sour cast to her expression to the minimum. She was getting what she wanted and she obviously hated the fact that she owed it to Kai.

Ziede stepped to Kai’s side. He could feel her relief and gratitude through her heart pearl, though she didn’t let it show in her expression. She had just gotten Tahren back, she didn’t want to see her have to fight her Blessed relatives, even Saadrin. Kai told her silently, We need to handle this very carefully.

Ziede’s brow furrowed as she considered potential strategies. We can slip into the city and go straight to Nibet House. That was the residence that the Enalin delegation used in Benais-arik. They’ll offer us hospitality without question and Tahren can ask for an escort to the council.

Kai let out a long breath. They needed to send a message to Avagantrum. They needed clothes and supplies, having lost everything useful they had collected during their canal journey in the flood at the Summer Halls. It would be a longer trip home from Benais-arik, especially if Saadrin wanted to keep the ascension raft. Tahren still needed time to recover, whatever she said. There was one place where all this could be done conveniently and safely. We can stay at the Cloisters until Tahren’s finished with the council.

Ziede said, that will work, then ruined it by adding, Ramad will know better than to look for you there.

Kai glared at her. I’m not worried about seeing Ramad.

Ziede squeezed his shoulder and didn’t comment.

* * *

If Kai was traveling here for the first time and had no idea they were about to reach the outskirts of a city, Benais-arik would still announce its presence well in advance.

First the converging of small canals into a big one lined with rushes and scrub trees but with the water free of any overgrowth that might obstruct boats. Then the roads curving in across the grassy plain, some well-traveled and dotted with occasional resting places, usually a copse of trees shading a few wooden shelters or a stone dome protecting a well. From above, the old roads were still etched on the landscape. These had been the main routes before the Hierarchs, but they led to places that didn’t exist anymore. From the surface they were mostly buried under grass and dirt, only the occasional boundary stone visible.

The raft passed over a few tumbled ruins that had once been villages or large farmsteads, but the signs of life—long canal boats or flitting skiffs, ox-drawn wagons and striding wallwalkers—was a reminder of survival that Kai would never grow tired of watching.

Then farmlands overtook empty fields, with scattered trees pruned into cone-shapes to shade the delicate greens and other plantings, with the hardy crops stretched out around them in concentric circles. Dry stone walls enclosed clumps of houses. Little cookshops and tiny temporary markets sprung up along the widening road.

Then finally bustling caravanserais with gardens and stables as in the distance the domes and towers of the city rose up, golden in the glow of late afternoon. Sentry posts had marked their approach already; Kai caught flashes of light reflected off mirrors that meant messages were passing below. It wasn’t uncommon for ascension rafts to come and go, especially during the coalition renewal. But the news about the conspiracy must have spread through the Rising World cohorts by now, and the presence of a raft and where it would land would be reported to the city garrison.

Dahin dropped the raft a little lower and slowed to follow the main eastward canal in over the city’s outskirts. It was mostly houses below now, older extended family compounds with their own gardens, interspersed with clusters of two- and three-story dwellings of sun-dried brick, constructed for refugees and ex-soldiers. The streets were shaded by acacia and eucalyptus trees, interspersed with the basins of the canal docks and the water markets where boats drew up to sell their goods.

Closer to the city’s center, the streets were wider and lined by larger stone buildings. Domes were carved and painted in traditional designs, scenes, and figures from Arike legends and history, though with everyone’s clothes and hair and armor and weapons far more elaborate and unwieldy than anything anyone would ever have had in reality. The curved walls were dotted with latticed windows and balconies to allow the wind to weave through the rooms and corridors. Benais House was in the central cluster, along with the older city assembly and law courts. The envoy houses were all in the same area, interwoven with the grand market and public gardens and clumps of private houses that had survived both the Hierarchs and the post-war rebuilding. The Rising World’s Assembly didn’t stand out next to the far more elaborate Arike buildings, but that didn’t disguise its importance. Other coalition cities had Rising World Assembly buildings, but Benais-arik’s was the oldest and largest.

As Dahin brought the raft around, Kai caught a glimpse of the old palace on the far side of the city center. It was enclosed in walls that had been outmoded even in Bashasa’s time, a relic of the Arik’s martial past. That had been over long before the Hierarchs arrived, and the palace had been partly a home for the current ruling Prince-heir’s family and partly a place for housing and entertaining important guests. It was still that now; Bashat lived there.

Their destination, Nibet House, was on the outer edge of the circle of envoy houses. It was only two stories tall, built of local sandy gray stone and heavy wooden beams brought down from the forests of Enalin. The low stone wall around the entrance garden and a scatter of olive trees hid the view of the first level but the big windows on the second floor were all open to catch the breeze off the canal, their carved wooden screens and storm shutters propped open. From the House’s undisturbed calm, and the general air of business as usual from the streets around it, Kai thought Bashat must not have given in to any impulses to challenge Enalin over its failure to support the Imperial renewal.

Dahin aimed for an open stretch of grassy land between Nibet House and a copse of tall trees. There were no supplication towers in Benais-arik, or any other Arike city-state, since the last one had been burned and toppled during the war, so it was as good a landing place as any.

Warned by the raft’s slow descent, an Enalin official came out the open gate from the House’s walled garden. They were a short and heavyset figure, with dark brown skin and long dark ringleted hair tied back. They wore a light yellow Enalin-style caftan with painted designs, but no formal robes. In this season, the afternoon was a rest period for most of the city, when the sun was too hot for any strenuous activity. It wasn’t a custom the Enalin practiced in the cooler climate of their home region, but all the envoys followed it here.

As the raft thumped down on the grass, the official watched with a quizzical expression, but didn’t speak. This was Enalin hospitality, which allowed guests time to sort themselves out and declare their intentions before questioning why they might be here. A few curious house pages, all children around Sanja’s age, appeared in the doorway.

Tahren opened the gate in the raft and stepped out. She lifted a hand in greeting and said, “Tahren Stargard asks the gift of a favor from the Warden of Nibet House.”

“Please address me as Setar-en, and Tahren Stargard has no need to ask, any assistance will be gladly offered.” Setar-en’s gaze was alive with curiosity now. They had clearly recognized Tahren and probably Ziede as well. Dahin had slumped down on the bench beside the steering device, his face turned away. “Is the matter urgent, or is there time for the House to extend its welcome to you and your companions?”

That might have been a polite way to say that they appeared to be a disheveled group that looked obviously in need of some sort of help. Tahren said, “The House’s welcome would be a gift indeed, but Immortal Marshall Saadrin has a prisoner who we must present to the Rising World council immediately.” She didn’t bother to gesture to Saadrin, who had just dragged Vrenren out of the raft. “This concerns the conspiracy between rogue factions from Nient-arik and the Blessed Lands that I understand was revealed during the coalition renewal.”

Setar-en’s brow furrowed in concern. “I will assemble an escort and accompany you myself. The ambassador is attending the council in the assembly hall today. The Tescai-lin was called to affairs in Belith, at Ancartre, but we will send word to them of your safe return.”

“That would be much appreciated,” Tahren said. It would be much less awkward for Tahren and Saadrin to drag an Immortal Blessed prisoner through the streets with an escort from Nibet House.

Ziede stepped out of the raft and Kai started forward, but Dahin, still crouched below the railing, grabbed a handful of his battered coat and stuffed something into the inside hem pocket. It was flat, like a book or a packet of paper. Sanja and Tenes, following Ziede, hadn’t seen. Kai sighed and stepped down from the raft. Whatever it was, he would worry about it later.

As Setar-en turned back toward the House, Kai said, “I would ask if a message is to be sent to the Tescai-lin, that they could also be told that Kaiisteron is with Tahren Stargard.”

Setar-en met Kai’s gaze, startled, then recovered their poise quickly. “Of course. And this House is always open to Kaiisteron, in whatever form he takes.”

Kai hadn’t expected to be turned away, and if he had been it certainly wouldn’t have kept him from sending his own message to the Light of a Hundred Coronels. But he still felt the tension in his shoulders ease.

Setar-en invited them to wait in the shade of the House’s garden while an escort was summoned, and then strode back inside, sending the young pages scattering on various errands.

Kai and the others were led through the gateway to a set of stone benches and chairs under the shade of a large neem tree. Sanja was the only one who plopped down into a seat. Saadrin stopped just inside the gate with her prisoner. Either she disliked the idea of hospitality predicated on being one of Tahren’s companions, or was too polite to sully Nibet House’s grounds with Vrenren.

Ziede told Tahren, “I’m going with you.” Her expression was conflicted; she obviously didn’t want to let Tahren out of her sight, but the ongoing political storm wouldn’t be improved by either her or Kai’s presence. “I don’t want to be seen in the assembly, I’ll wait outside for you. Just don’t get kidnapped again.”

Tahren took Ziede’s hand and squeezed it. “Take your own advice.”

Tenes watched them with a worried frown. She signed, I’ll wait with Sister Ziede. It’s always safer with two. She turned to Kai. Will you be here?

Kai said, “I’ll go on to the Cloisters.” Flying so long in the raft with the wind whistling in his ears made his head feel like there was a vise tightening around it. He wanted to get away somewhere he could make plans and not worry about being seen. At least he didn’t have to decide what to do with the ascension raft. Dahin hadn’t followed them into the garden and Kai expected that he and the raft would be gone by the time Setar-en reappeared with Tahren’s escort. He kept his sigh internal; either Dahin would turn up later or he wouldn’t, there was no telling. “I’ll walk from here.”

Sanja jumped up and grabbed Kai’s hand. “I’m going with you.”

Kai looked down at her, lifting his brows pointedly. He had meant to send her with Tenes and Ziede. Sanja was not intimidated and her face set in a stubborn glower. She added mulishly, “I don’t want to stay here.”

Kai realized the conversation with Setar-en had taken place in formal Nibetian, and that Sanja hadn’t understood it. She hadn’t seemed worried about being abandoned anywhere else, but maybe being back in a city again had woken suppressed fears. He said, “You’re not staying here.”

The tense set of Sanja’s shoulders eased minutely but she didn’t let go of Kai’s hand. Take her with you, Ziede said silently. Perhaps she’ll keep you out of trouble.

Hah, Kai replied. He had carted Ziede’s daughter Tanis around for a year when she was younger than Sanja, when the Immortal Blessed were still trying to kill Tahren, and it hadn’t kept either one of them out of trouble. But there was a first time for everything. He told Sanja, “You’ll come with me to the Cloisters.”

Sanja’s frown smoothed but she was apparently too tired and cranky to let the impulse to argue go entirely. She demanded, “What’s that?”

“You’ll find out when we get there,” Kai told her.

Ziede said, “We’ll go ahead, then. Meet us in the plaza outside the hall.” She kissed Tahren and walked out the gate. Tenes signed a quick farewell-for-now and followed. Saadrin busied herself dragging Vrenren out of their way, probably so she could use it as an excuse not to make any formal farewell to Ziede that might indicate that their temporary allyship was in any way permanent.

Using her pearl, Ziede told Kai silently, Dahin’s left with the raft. Are we surprised?

No, Kai told her. He knew she had also told Tahren, when Tahren let out her breath in the nearly inaudible sigh, the one most associated with whatever Dahin had done now. Kai said aloud, “He’ll be back.”

Tahren said, “You’ve known him better than I have, over the years.”

If she was anyone but Tahren, Kai would have said her expression was bleak. He said, “Are you all right?”

She glanced down at him and admitted, “I am torn between the overwhelming desire for a hot bath and an anger so intense I could bite through my sword blade.”

That was better. “If you bite any councilors, be sure to make it count.”

Setar-en’s promised escort of four Enalin warriors hurried out of the wide doorway. They wore the knee-length version of Enalin formal caftans over wide pants and tough boots. They didn’t carry weapons, since that wasn’t encouraged within Arike city borders, and in the diplomatic center of the Rising World not even the Prince-heirs’ cadres were allowed to go armed in public. Setar-en strode out after them in a formal robe hastily thrown on over their caftan. Tahren nodded to Kai and said, “I’ll see you later.”

Adjusting the fold of their collar, Setar-en said, “You will not accompany us, Kaiisteron?”

“Not at the moment.” As entertaining as appearing suddenly before the council and creating a sensation similar to a firepowder-filled gourd tossed into a legionary’s campfire might be, Kai wasn’t tempted. It was much better to let Tahren handle this. He added, to stop any possible argument, “I’m going to the Cloisters.”

Setar-en glanced down at Sanja, who was drooping a little now that the excitement was over. Then they kindly offered the use of one of the House’s hired canal boats. Kai decided not to be an idiot and accepted it. There would be far less chance of anyone intercepting them along the way.

Setar-en sent another page to arrange the boat, then gestured for Tahren to take the lead. Kai found himself a little uneasy to see Tahren walk away and said, “Careful.”

She lifted a hand in acknowledgment and fell into step with Setar-en and their escort as they walked out the gate. Saadrin followed her, dragging Vrenren in her wake.

A page brought another Enalin official, a tall person who by their wrinkled caftan had probably been taking their afternoon rest. They introduced themself as Second Warden Amren-nar, and they led Kai and Sanja through the garden and around the side of the House, through a gate to the private canal dock.

The stone dock was shaded by water trees, and the boat waiting there was a light pole skiff used for quick journeys. It was piloted by two women who had the light olive-tinged skin of Palm but the dark curly hair and dress and accents of the Arik. They were clearly used to doing Nibet House’s formal commissions; they didn’t try to speak to Kai, and they didn’t react to him at all except for the polite interactions necessary to board and get settled under the boat’s little awning. They might have no idea that he wasn’t a mortal; Amren-nar solved the problem of Kai being spotted as a demon by handing him their own sun hat, made from coiled braids of scrap grass silk. It shaded Kai’s eyes enough to make recognition difficult, especially from a moving boat.

With the cool breeze and the warmth of the afternoon sun, Sanja fell asleep almost immediately, slumped against Kai’s side. The pilots poled the boat swiftly along out of the city center.

They took a branch of the canal that angled away through the tree-shaded parkland, passed a cluster of docks for the market, then under a bridge arched high enough that the pilots didn’t have to duck. Then an area of streets lined with tall trees and old stone structures that had once been cargo storage and merchant centers before being turned into post-war housing. From the many small boats tied up along the canal’s walkway, the awnings for temporary outdoor workshops, root gardens planted on the balconies and rooftops, and the number of goats wandering around, these areas were well occupied and usually busy, but they were quiet and drowsy in the afternoon.

They left the life of the neighborhoods behind for more docks packed with canal boats, equally sleepy during this lull in the day, in-use cargo houses, and grain silos. Then vine-wrapped trees closed in on the banks and three tall arches loomed up. They were the crumbling remains of an old bridge, its reddish stone pitted and broken. Water still fell from the third broken arch, the end of the aqueduct it had once carried.

The bridge led to a high wall along the bank, battered and cracked, with a collapsed earthwork below it, flowering plants and thorn brush growing amid the tumbled blocks at its feet. The wide stone landing platform for barges was strewn with rubble and overgrown with water weeds. Near it, a jagged opening had been knocked through the fortification to form a makeshift gate. To one side of it stood a stone bench shaded by a scrub tree, where offerings had been left—beads, braided grass bracelets, lizard skulls, tiny cloth dolls, figures made of clay or carved wood, wilting flowers, small bowls of grain, and a lot of fruit, most of it relatively fresh. Kai gently nudged Sanja awake and said, “Here is fine.”

The pilot in front glanced back, brows lifted, but didn’t comment. They poled the boat over toward the bank. The silence was broken only by the rising hum of the cicadas in the trees.

The current wasn’t strong, and the two pilots held the boat steady as Kai swung Sanja over to the platform and then stepped up after her.

Sanja looked around, already alert. A life on the streets had given her the ability to wake immediately. “This is where we’re going to stay? What is it?”

“The Hierarchs had it made as a place to worship them when their usurper took over the city,” Kai explained.

As they made their way off the cracked platform to the shore, one of the pilots called out, “Are you him?”

So much for his disguise. Kai stepped to the offering slab and picked up a couple of figs. He tossed one to Sanja before he turned to regard the pilots, head tilted in inquiry.

One made a quick respectful salute, looking away. The other said, “My grandmothers were at Saisun Breach.” She nodded, and pushed the boat away from the platform.

Kai watched the pilots guide their boat back into the current. She hadn’t said what side her grandmothers had been on, but it didn’t matter much now. Kai took Sanja’s hand to lead her through the makeshift gate in the wall.

Past the earthwork, there was a field of more rubble, broken down until it was no more than knee-high at best. Kai took the path through, its twists and turns invoking various local spirits to discourage anyone susceptible to their mild influence. Anyone who wasn’t a Witch.

At the end of the path was a set of broad steps leading up to the foundation of a large building. Atop it now stood nothing but a few weathered pillars, the remains of a once grand colonnade, all in ruins now. But the archways built into the foundation, bracketing the stairway, were open into dark passages that led inside.

Kai felt the little spirits in the rubble plucking at his coat and skirt. Sanja twitched a little and brushed a hand over her hair, as if something had tugged on it. To distract her, he said, “To make this place, the Hierarchs tore down a very old hospital that was here, the first one in the city, and a school that Bashasa’s father had built. Anyone could go there to learn how to draw and paint and do carving.”

And it was where artworks were exhibited for all the world to see, anyone in the Arik or outside it, no matter their station, Bashasa had said, one late night huddled beside a banked fire, waiting for the right moment to start an attack. All that work, done by so many hands, over so many years, all broken to dust and kindling, or stolen for their servant-nobles’ pleasure.

Kai finished, “So when we killed the Hierarchs, the people of Benais-arik destroyed this place, and gave it to the Witches for their own.” I want them to dance in it, Bashasa had said, to grind the Hierarchs’ finery under their heels.

“Bashasa is the one who was your friend, right?” Sanja said as they climbed the steps toward the leftward passage. “The one Ramad kept asking all the questions about?”

“That’s right.” Ramad hadn’t seemed to realize just how much Sanja had eavesdropped.

She said, “Anything you say about him, I won’t tell anyone.”

It struck Kai so hard that he stopped in his tracks and stared down at her. She looked up at him, her face solemn. He squeezed her hand, and they walked on.

Once they passed under the arch into the cool gloom of the passage, the spirits’ invisible hands fell away. Guttering candles made of bayberry and palm oil were stuffed into various niches to light the way, dancing shadows over the tile of the barrel-vaulted ceiling high overhead. Kai threaded their way through the passage, past a set of arched doorways that led deeper inside. It was quiet, but it was the hush of listening, not the silence of an uninhabited place. His return hadn’t gone unremarked.

They came to a chamber where wide steps led up past pillars where the carvings had been methodically bashed away, then to a long, high-ceilinged space. It had been a private audience room, mostly used for rewarding or punishing the Hierarch servants who had been given control of Benais-arik. Half columns lined the walls and on the north side were floor-to-ceiling windows looking out over the earthwork and the canal. Even though the louvers were open, there were only a few dead leaves and some windblown dust in the corners, which meant someone had been taking care of these rooms. Probably the Cloister Witches who lived here year round. The cool air carried nothing except the scent of wet earth and sun-warmed grass and trees.

The gray stone paving the floor had held up well and was only a little cracked, and the blue glass inlay in the wall tile was still bright. All the gold and inlaid jewels and the murals on the coffered ceiling had been scraped out when the Hierarchs had been driven away, leaving hollowed-out sockets and raw stone. At the far end, there was a dais with three broad steps, where the Hierarch or their servant-nobles would have stood to pass judgement. Kai walked up the steps and through the archway beyond, into the smaller anterooms that led into the rest of the suite. The wooden panels were still closed over the windows back here and it was darker and dustier.

Sanja trailed after him, asking dubiously, “You used to live here?”

Kai stopped in the large retiring room and started to wrestle the creaky shutters open, dislodging spider webs, lizards, and some angry beetles. There was a dais here too at the back, supporting a wide curved bench carved out of stone, all the inlay and carvings bashed off it. He told Sanja, “For a while. And we’ve been back off and on.” As he got the windows uncovered, light and a fresh breeze flooded the room, illuminating the faded mural on the far wall. It had once shown the Hierarchs bringing the gifts of civilization to the primitive north, which was a fairly standard subject for the places the Hierarchs had built for their servant-nobles to rule from. By the time Kai and the others had first seen this one, someone had scratched off the Hierarchs’ heads and daubed red paint around their necks. Dahin had called it “bringing the historical record up to date.” Kai added, “It was meant as a summer residence and it’s not especially comfortable in the rainy seasons.”

“Is that why you live somewhere else now?” Sanja pushed a broken floor tile back into place with her sandaled foot. The wooden chests they had left behind were still sealed, stacked back against the mural wall so any rain that got through the shutters wouldn’t reach them. Two large squat metal braisers stood on either side of the room, the preferred Arike method for heating during the cooler months, both empty and swept clean.

Kai started to say yes, then he thought of what Sanja had said earlier, and about confidences. He said, “Bashasa died, and I didn’t want to live in this city anymore.”

Sanja glanced up at him, then nodded matter-of-factly. They wandered through the rest of the suite, and Kai opened more shutters. Leaving Sanja pulling on the pump lever in the bathing room to chase the ants out of the basins and drains, Kai went back to the carved chests in the retiring room. They were actually Immortal Blessed preservation chests, abstract sun symbols carved around the rims inset with flaked gold. When Kai broke the seals and opened them, the decades-old orchid petals scattered on the top layer released a breath of clean fragrance.

Inside were rolled blankets and rugs, cushions, copper pans and two kettles, a drinking set, some heavily embroidered silk coats and other clothing, a lot of stray jewelry, some bags of old coins, Benais-arik tokens, bundles of old maps and bound books, carefully wrapped bath powders, and a small carved box of tiny jars and vials for makeup and oils. Ziede would be pleased to see that; she might not have any idea it had been left here. He reached for her pearl lightly, just to check on her, and got a sense of a shaded spot somewhere out in the plaza to one side of the Rising World Assembly, near a vendor selling fruit water flavored with sugarcane and spices.

Ziede was distracted, probably listening to the council meeting through Tahren’s pearl. Hopefully she and Tenes wouldn’t have to wait long. Knowing Tahren’s current mood, perhaps she would say what she had to say, then just walk out, leaving Saadrin to answer any questions.

Kai opened the bag of tokens and sifted through it. Each one was a memory, and some were almost smooth, worn down by their years, just like he was. A light patter of footsteps sounded from the audience room and Kai dropped the bag back into the chest and pushed silently to his feet. By the time he reached the archway, several Cloister Witches, veiled and wearing an eclectic mix of colorful clothing, gathered in the room. On the dais they had left two clay pots with lids, a ceramic jug, and a basket of palm fruit and water apples. As Kai leaned down to examine these offerings, the package that Dahin had jammed into his hem pocket thumped his knee, reminding him it was there. One pot held lentils with what smelled like turmeric, garlic, and onion and the other was a bean porridge with fried peppers scattered on top. The jug held saffron-spiced goatmilk. He called, “Sanja, come and eat.”

Two

Kai retrieved some cushions from the chests and slumped comfortably in the Hierarch’s carved chair on the dais in the retiring room, eating palm fruit and reading.

The Cloister Witches returned to carry in some rolled-up mattresses. Then Sanja took charge and unpacked all the chests, and with the Witches’ help seemed to be setting up the rooms to her satisfaction. She went in and out wearing various combinations of the stored jewelry, sweeping, rolling out rugs in the retiring room, finding charcoal for the braisers, unwrapping the drinking set. Then two Witches moved a carved wooden divan to the retiring room from the back of the suite, and Sanja directed them where to put it. It appeared she had learned enough Witchspeak to give people orders. Kai told her, “You know they aren’t servants, they just live here.”

“I know,” Sanja said as the Witches stuffed the frame with cushions and another pair carried in a second divan. “I tried to give them some of our money, but they wouldn’t take it.”

Kai gave up and went back to his reading. Dahin’s package had turned out to be a sheaf of pages stitched together with heavy thread. At first Kai thought it was the beginning of another history, like the ones Dahin had written years ago, but more personal; it started with a recollection of Dahin’s time in the hostage courts of the Summer Halls. But it was more than that; it was an explanation of his theories about the Hierarchs’ homeland, which had always been thought to be somewhere in the Capstone of the World near Sun-Ar. Dahin had said his thoughts were unformed; this manuscript, written in neat Old Imperial with a lot of crossouts, was where he had evidently been trying to organize them.

The theories Dahin had outlined to Kai didn’t seem unformed; they built toward a conclusion that just needed a little more proof to seem inevitable.

Sanja reappeared wearing a silk wrap-tunic with beaded hems and a pair of cotton pants only a little too big. Someone had helped her fix her hair back into twists and she wore a figured gold head band set with tiger eye and carnelian which Kai had last seen on the dead body of the Hierarch servant-noble in charge of destroying the contents of Benais-arik’s scholars guild libraries. He hoped whoever had cleaned the gore off it had done a good job.

Sanja carefully set a cup of saffron milk on the arm of the throne. It was from the drinking set, a very fine one of clear glass veined with brilliant red pigment with polished copper holders. Odd how Kai remembered that hair band, seen for only one fraught moment, but not this drinking set. Was it his or Ziede’s, had it been a gift? Had he ever actually seen it before it had been packed away or had he used it every day and just forgotten it, along with everything else he had tried to forget?

Shaking him out of his thoughts, Sanja said, “Do you know when the others are going to be back? Satli said they want to make fried cakes.”

Kai reached for Ziede again, felt a sense of disgruntled relief that wasn’t his own. “I think they’re on the way.”

* * *

When Kai heard the others come up the steps into the audience room, late afternoon had just touched the edge of evening and the hooting of tree frogs had joined the cicada chorus. Ziede had used her pearl to tell him that all was well, but it was still a relief.

Ziede swept in and through the anteroom, waving a hand. “Is the bath working? Good.” She vanished through the archway into the back of the suite, Tenes in her wake. Tahren followed at a more sedate pace and dropped down onto the divan near the windows, letting out her breath in a long sigh.

Kai closed Dahin’s book, marking his place with a finger. “How was the council?”

She frowned, rubbing the bridge of her nose. Kai had seen Tahren in various states of exhaustion, repressed fury, and frustration, and this was definitely a combination of all of those. She said, “The effect of the failed Imperial Renewal was obvious. The council hall had been rearranged, to remove Benais-arik’s seat from the center of the circle and return it to its old place among the rest of the speakers. Bashat was very good at pretending nothing particularly unusual had happened, and all the other speakers seemed very polite about it. If a throne had made an appearance at any point, it had been discreetly removed.”

Though Kai had the Enalin ambassador’s word that Bashat’s bid for Imperial control had failed, it was unexpectedly reassuring to have this confirmation, seen with Tahren’s eyes if not his own. “Good. And Bashat must have been delighted to see you back so soon.” They knew Bashat had revealed the Nient-arik faction’s conspiracy with Immortal Blessed Faharin and his people just before the failed Imperial renewal vote. Bashat would have expected Tahren to return with Ramad, who had been tasked with locating her. Bashat was a strategist who kept his head; he might not have anticipated that the conspirators would panic and make their situation worse when they realized they had been discovered. And Ramad had had no opportunity to send a message until Kai left him at the river trading post yesterday.

“Bashat was expert at concealing his consternation.” Tahren’s expression turned sardonic. “Vanguarders had been sent to search for me throughout the coalition, and the speakers were expecting reports of their progress, not for Saadrin and me to walk in with the warden of Nibet House and one of the conspirators’ minions as a prisoner.”

Kai almost wished he had seen it. “It caused a sensation.”

“It did. Saadrin took the speaker’s circle at the Enalin ambassador’s invitation and told the story as she knew it. Then she vowed to find every member of the Blessed who had participated in the treachery and bring them to justice before all the Rising World.” Tahren grimaced. Like Kai, she had worn out much of her interest in vengeance over the years. “It will keep her busy, at least. Setar-en said the speakers for Nient-arik had already offered formal apologies and reparations on behalf of their erring countrymen. Setar-en thought they were sincere; two are from the artisan and farmer guilds, only one is a Prince-heir.”

“That’s interesting.” If the old Prince-heir families were losing ground in Nient-arik, that would explain why a faction had split off and made this bid for power. Besides the fact that Bashat’s own bid for power had stirred up old feuds and given hope to greedy fools like the Immortal Blessed Faharin. “They must be scrambling to clean their house.”

“One would hope.” Tahren continued, “The Immortal Blessed speakers maintained deeply embarrassed stoic silence, for the most part. They were horrified to see Saadrin. One of them is Garoden, a distant relation. He tried to take the speakers’ circle at one point and a speaker for the Cahar Mountain Alliance suggested that he not ‘make it any worse.’ Amazingly, he heeded their words.”

That would have been a joy to see. In this new body, if Kai had found a way to disguise his eyes, it would have been easy. Vrenren’s eyes had been available, but their temporary truce with Saadrin probably didn’t go that far. “Did Saadrin explain how Faharin died?”

“She said he was killed by a companion who was defending her person.” That was an Immortal Blessed code that meant revealing the name would cause an internecine war, so it was better not to. It was unexpectedly generous of Saadrin; Dahin didn’t need any more attention from the Immortal Patriarchs. The Rising World council wouldn’t care, as they would have turned Faharin over to the Blessed for justice anyway, if he had been brought in as a prisoner. As Vrenren would be, once he testified. Tahren added pensively, “They will assume it was me, which is well enough. Saadrin also did not accuse you and Ziede of stealing that Blessed ship, which frankly surprised me.”

“We did steal it,” Kai said, but they had stolen it from the expositor Aclines, who had received it from an Immortal Patriarch for the purpose of helping destroy the treaty between the Blessed Lands and the Rising World, so Saadrin had possibly not wanted to dwell on that any more than she already had.

“She did tell them you and Ziede freed both of us from the conspirators, though not how. She can’t, without telling them that a finding stone still exists.” Tahren’s expression tightened. “Many suggestions had been made as to why you and Ziede had disappeared before the Imperial Renewal. That you were searching for me, that you were in league with the conspiracy, that you were pretending to be in league with them in order to destroy them.”

There were days when Kai missed his fangs. “That sounds like Bashat’s work.”

“Indeed.” Tahren’s voice was hard as steel. “I clarified that you and Ziede had also been imprisoned, and that you had taken a new form because your former host had been destroyed.” There had been no reason to withhold that information, since Ramad and Cohort Leader Ashem knew and would report to Bashat soon enough. Tahren looked away, pressing her lips together at an unpleasant memory. “I made sure I was meeting Bashat’s gaze. He knows I know.”

Maybe it was better that Kai hadn’t been there after all. Watching Immortal Blessed squirm wasn’t quite worth it. “Bashat must have been relieved when you didn’t denounce him.” Only partly joking, he eyed Tahren. “You didn’t, did you?”

Tahren’s mouth did not quirk even briefly. “I did not. He can stew in uncertainty until his spy Ramad arrives and tells him the rest of the story. Then he can stew in uncertainty forever, knowing that you can destroy him with a few words. Or he’ll try to have you killed.”

Kai shook his head, dismissing it. “He’s not that unwise.”

Tahren didn’t comment on that. “As we were leaving, the Enalin envoy indicated that there was not as much support for Benais-arik’s Imperial ambitions as Bashat might have hoped. Once the Enalin’s opposition was announced, most of the other speakers followed their lead.”

Bashat must have had some inkling that his plan wasn’t favored. “That’s why he wanted to use the Nient-Blessed conspiracy to promote himself.”

“Yes.” Tahren met Kai’s gaze. “I know you were once charged with Bashat’s protection, but I would like to strangle the little shit.”

At that opportune moment, Ziede walked in, her brow furrowed in confusion. Her hair was wrapped up in a towel and she wore a bathing robe. She looked as if she might have just flung herself into the bath basin and climbed out again. Sanja trailed out after her, yawning. Ziede demanded, “Did we leave it like this? I thought everything was packed or stored.”

Tahren frowned down at the divan she was sitting on as if she had just noticed it.

“Sanja and some of the Cloister Witches unpacked,” Kai told her.

“Good.” Ziede smiled down at Sanja, then did a double take. “Take off that hair piece, I’ll find you a better one.”

* * *

As they were sharing out the food that the Cloister Witches had brought, Ziede made everyone take real baths, with soap and the fragrant oils for hair and skin, not that they needed much persuading.

By the time Kai finished his, the twilight sky had darkened and the breeze turned cool, and someone had lit the old stone candlelamps. Once he had wrangled the still damp curling mass of his hair into some sort of order with a couple of bronze pins from the assortment Sanja had unpacked, he walked back out to the retiring room. Sanja had gorged on fried cakes and fallen asleep on a divan, with an old silk court coat for a blanket. Ziede and Tahren sat on the other divan, leaning into each other, and Tenes curled on a stone window seat looking out onto the moonlit canal. She was wrapped up in an Enalin-style painted caftan, which Kai also had no memory of seeing before, let alone packing it away when they left this place. Kai took the opposite side of the window seat and signed to her, feeling better?

With the dirt washed away, the bruises stood out against her pale skin, but she signed an assent. This place is lovely. Will we stay here long?

For tonight at least, Kai told her. Why? Did you want to stay?

I spoke to some of the Cloister Witches. One called Adenhar thinks I look like someone she knows in the stone hill country of Palm. She said that there are others there who can speak to the earth like I do, and some have my eyes.

“That’s good news,” Kai said aloud, but she seemed a little troubled by it. He signed, Isn’t it?

She hesitated, and signed, I also wish to stay with you and Ziede and Sanja.

If you can find your family, you should, he told her. There had to be people missing her. Unless Aclines had killed them all, but he wasn’t going to say it. There was no way that hadn’t already occurred to her. Even if you decide to leave with us again afterward.

She still looked uneasy. What if they don’t want me back? I was an expositor’s familiar. I’m afraid of what they might think of me.

Families are terrifying, Kai agreed. He couldn’t reassure her on that score. Think about it, there’s no hurry.

“I don’t want to move, possibly for the next century.” Ziede yawned. She nudged Tahren. “Do you think you’ll need to return to the council?”

“They may still have questions. I’m not sure I have much intention of answering them,” Tahren admitted. “The situation seems stable now, from what I was told and what I observed. Before Saadrin and I interrupted, the council was in the process of finally admitting the Cloud Islands as a full member of the coalition.”

Ziede told Kai, “There was no attempt to suggest any replacement for Bashat. Apparently getting yourself voted in as emperor and then decisively voted out again was not a journey any of the other speakers are eager to embark on. Not that they’d be able to. If the Grale speaker tried something like that the whole southern region would simultaneously burst into riot.”

Kai wasn’t so sure of that. “In the old days, maybe.” The Arike Prince-heirs were in the best position to pull off a power grab, as evidenced by how far Bashat had gotten. The members of the Rising World coalition were governed in many different ways, and many of the speakers didn’t have that kind of inherited power and support. “Too many of them don’t remember anything but the Rising World. They’ve gotten complacent.”

The clever thing Bashat had done in his tenure as emperor was that he hadn’t fundamentally changed the way the Rising World coalition worked. Bashasa’s post-war food distribution schemes were still in place, coalition resources still went to all the various ministrant guilds, to teaching archives and libraries, to safeholds and hospitals. The rules governing trade and criminal punishments and forbidding indenture and slavery were the same. The coalition still settled disputes by arbitration in assemblies and not by force. Anyone could still go to a Rising World council hall and appeal for help or redress. But Bashat, through means subtle and blatant, had made himself seem the source of all that. That these things were gifts instead of something that had been fought for, as they had taken the world back from the Hierarchs step by blood-soaked step. Instead of something built by years of work by Bashasa and the Tescai-lin and Prince-heir Hiranan and all the others across the Arik and Enalin and Palm and Belith and Ilveri and Grale and beyond who had made the coalition into something that could last.

Kai said, “Do you want to leave tomorrow?” He could make that happen. He knew where to go to find someone willing to lend or rent them a boat that could take them to Bardes-arik on the canal, and from there they could buy their own transport under less scrutiny. “There’s something I need to do tonight, but we could start off in the morning.”

Tahren glanced at Ziede, smiled, and said, “Let’s decide that when we wake up.”

Ziede eyed Kai. She had obviously noted that he hadn’t said what he needed to do. “What did Dahin give you so surreptitiously?” Tahren lifted her brows in surprise. She hadn’t seen Dahin pass the package to Kai.

“It’s a journal of what he’s been working on.” Kai explained, “He was at the Summer Halls trying to uncover a wall carving in one of the Hierarchs’ sanctuaries. There was a map there. He thought it might show the Hierarchs’ home, or the route they took to get here.”

Tenes was listening alertly. Kai wasn’t sure how much of her education Aclines had left her when he took her memories. Much of this might be new information to her. She signed, Didn’t they land in the Arkai, at the deserted city we saw?

“That was one of the places, yes.” The Hierarchs had first landed in the Arkai, then spread out north and west overland, while hitting multiple cities along the east and south coast. Dahin had theories about that too. “And we know they came through the south continent. But before that, it’s all speculation.”

Ziede watched him thoughtfully. “From your expression, this isn’t just another history.”

“Wait.” Tahren’s brow furrowed. “When you say uncovering—”

“He was diving in the flooded rooms. Not under the weed mat, but still. He obviously thought it was important.” As a Lesser Blessed, Dahin wouldn’t be infected by any of the number of waterborne diseases that caused mortals to vomit or shit themselves to death without proper treatment. He could still have drowned, though.

“The weed mat.” Tahren winced but didn’t otherwise comment. “And did he find what he was looking for?”

“Partly. He has a lot of sources noted here. He was searching archives all over the east.” So many archives had been destroyed by the Hierarchs, it made this kind of search difficult. It was one of the reasons that Bashasa had made sure the Rising World put resources into rebuilding the libraries as soon as the war was over. “He thinks the Enalin who went to Sun-Ar were wrong about where the Hierarchs came from.”

Ziede’s expression was closing in, turning worried; she clearly saw the direction this was going. Tahren, exhausted and liking to have things clearly spelled out, said, “And he thinks this is important because…”

It still gave Kai a chill in his spine to say this aloud. “Because if the Enalin were looking in the wrong place, then they were wrong about there being no trace of the Hierarchs in the Capstone of the World. They could still be up there.”

Copyright © 2025 by Martha Wells

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...