- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

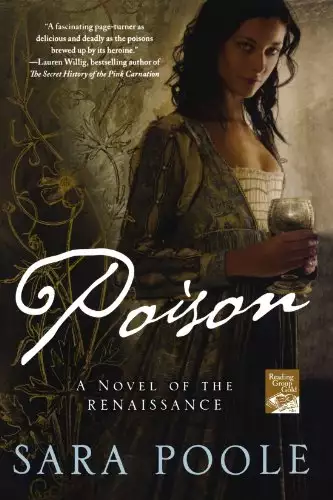

Synopsis

In the simmering hot summer of 1492, a monstrous evil is stirring within the Eternal City of Rome. The brutal murder of an alchemist sets off a desperate race to uncover the plot that threatens to extinguish the light of the Renaissance and plunge Europe back into medieval darkness.

Determined to avenge the killing of her father, Francesca Giordano defies all convention to claim for herself the position of poisoner serving Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia, head of the most notorious and dangerous family in Italy. She becomes the confidante of Lucrezia Borgia and the lover of Cesare Borgia. At the same time, she is drawn to the young renegade monk who yearns to save her life and her soul.

Navigating a web of treachery and deceit, Francesca pursues her father's killer from the depths of Rome's Jewish ghetto to the heights of the Vatican itself. In so doing, she sets the stage for the ultimate confrontation with ancient forces that will seek to use her darkest desires to achieve their own catastrophic ends.

Release date: August 3, 2010

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Poison

Sara Poole

The Spaniard died in agony. That much was evident from the contortions of his once handsome face and limbs and the black foam caking his lips. A horrible death to be sure, one

only possible from that most feared of weapons: "Poison."

Having pronounced his verdict, Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia, prince of Holy Mother Church, looked up, his dark eyes heavy-lidded with suspicion, and surveyed the assembled members of his household.

"He was poisoned."

A tremor ran through guards, retainers, and servants all, as though a great wind blew across the gilded reception room shaded by the columned loggia beyond and cooled in this blazing Roman summer

of Anno Domini 1492 by breezes from the gardens filled with the scents of exotic jasmine and tamarind.

"In my house, this man I called to serve me was poisoned in my house!"

Pigeons in the cotes beneath the palazzo eaves fluttered as the great booming voice washed over them. Roused to anger, Il Cardinale was a marvel to behold, a true force of nature.

"I will find who did this. Whoever dared will pay! Captain, you will—"

About to issue his orders to the commander of his condotierri, Borgia paused. I had stepped forward in that moment, squeezing between a house priest and a secretary, to put myself at the front of

the crowd that watched him with terrifi ed fascination. The movement distracted him. He stared at me, scowling.

I inclined my head slightly in the direction of the body.

"Out!"

They fled, all of them, from the old veterans to the youn gest servant, tumbling over one another to be gone from his presence, away from his terrifying rage that turned the blood to ice, freed to whisper

among themselves about what had happened, what it meant, and, above all, who had dared to do it.

Only I remained.

"Giordano's daughter?" Borgia stared at me across the width of the reception room. It was a vast space carpeted in the Moorish fashion as so few can afford to do, furnished with the rarest woods, the

most precious fabrics, the grandest silver and gold plate, all to proclaim the power and glory of the man whose will I dared to challenge.

A drop of sweat ran down between my shoulder blades. I had worn my best day clothes for what I feared might be the final hour of my life. The underdress of dark brown velvet, pleated across the

bodice and with a wide skirt that trailed slightly behind me pressed down heavily on my shoulders. A pale yellow overdress was clinched loosely under my breasts, a reminder of the weight I had lost since

my father's death.

By contrast, the Cardinal was the picture of comfort in a loose, billowing shirt and pantaloons of the sort he favored when he was at home and relaxing, as he had been when word was brought to him

of the Spaniard's death.

I nodded. "I am, Eminence, Francesca Giordano, your servant."

The Cardinal paced in one direction, back again, a restless animal filled with power, ambition, appetites. He gazed at me and I knew what he must see: a slim woman of not yet twenty, unremarkable in looks except for overly large brown eyes, auburn hair, and, thanks to my fear, very pale skin.

He gestured at the Spaniard, who in the heat of the day had already begun to stink.

"What do you know of this?"

"I killed him."

Even to my own ears, my voice sounded harsh against the tapestry covered walls. The Cardinal paced closer, his expression that of mingled shock and disbelief.

"You killed him?"

I had prepared a speech that I hoped would explain my actions while concealing my true intent. It came in such a rush I feared I might garble it.

"I am my father's daughter. I learned at his side, yet when he was killed, you did not consider for a moment that I should take his place. You would have for a son but not for me. Instead, you hired this . . .other—" I caught my breath and pointed at the dead man. "Hired him to protect you and your family. Yet he could not even protect himself, not from me."

I could have said more. That Borgia had done nothing to avenge my father's murder. That he had allowed him to be beaten in the street like a dog, left in the filth with his skull crushed, and not lifted

a hand to seek vengeance. That such a lapse on his part was unparalleled. . . and unforgivable.

He had left it to me, the poisoner's daughter, to exact justice. But to do so, I needed power, paid for in the coin of one dead Spaniard.

The Cardinal's great brow wrinkled prodigiously, leaving his eyes mere slits. Yet he appeared calm enough with no sign of the rage he had shown minutes before.

A flicker of hope stirred within me. Ten years living under his roof, watching him, hearing my father speak of him. Ten years convinced that he was a man of true intelligence, of reason and logic, a

man who would never be ruled by his emotions. All down to this single moment.

"How did you do it?"

He was testing me; that was good. I took a breath and answered more calmly.

"I knew he would be hot and thirsty when he arrived, but that he would also be cautious of what he drank. The flagon I left for him contained only iced water, pure enough to pass any inspection. The

poison was on the outside, coating the glass. He was sweating, which meant that the pores of his skin were wide open. From the moment he touched the flagon, it would have been over very quickly."

"Your father never mentioned such a poison to me, one that could be used in that way."

I saw no reason to tell Il Cardinale that I, not my father, had developed that particular poison. Likely, he would not have believed me anyway. Not then.

"No craftsman gives away all his secrets," I said.

He did not reply at once but came closer yet, so close that I could feel the heat pouring off him, see the great swathe of his bull-like shoulders blocking out the light. The glint of gold from the cross

dangling against his barrel chest caught my gaze and I could not look away.

Cristo en extremis.

Save me.

"By God, girl," the Cardinal said, "you have surprised me."

A momentous admission from this man who, it was said, knew before any other which swallow would alight first on any tree in Rome and whether the branch could hold its weight.

I took a breath against the tightness of my chest, looked away from the cross, away from him, out through the open window toward the great river and the vast land beyond.

Breathe.

"I would serve you, signore." I turned my head, just enough to meet his gaze and hold it. "But first, you must let me live."

2

The servants came and went, removing all trace of the Spaniard.

They carried in my chests, brought food and drink, and even turned down the covers of the bed framed in wooden posts of carved acanthus where once my father had slept and now I

would.

Tasks completed, they filed out silently, all except the last of them, an old woman close enough to Heaven to have little to lose. Skittering away, she hissed: Strega!

Witch.

A cold shiver ran through me, though I was careful to give no sign of it. Such a word would never have been applied to my father or to the Spaniard or to any man possessed of the fearsome but respected skills of a professional poisoner. But it would be applied to me now and forever, and I was helpless to prevent it.

They burn witches. The terrifying auto-de-fé is not limited to its point of origin in Spain. It has spread to the Lowlands, the Italian Peninsula, all of Europe. For the most part, the flames consume those

accused of heresy, but how easy it is to indict a man or woman—almost always a woman— or even a child accused of the even graver sin of trafficking with Satan. Anyone too conversant with ancient

healing, too knowledgeable about plants, or simply too different from others may end as fuel for the fires that char human skin, sizzle human fat, crack human bones, and reduce to ashes all that is hope

and dream.

I turned, intending to distract myself by unpacking the chests, then turned again suddenly, a hand clamped over my mouth. On my knees, I yanked the piss pot from beneath the bed and crouched over it as the contents of my stomach spewed out, a bitter stream that all but choked me.

Disgustoso!

Do not think I am prone to such infirmity, but the events of the day, the desperate gamble I had been forced to take and the terror of mortal sin it brought, overwhelmed me. I lay where I was, unmoving.

Exhaustion bore me away as on a fast-running tide flowing swiftly beyond any sight of shore.

The nightmare came almost at once. The same dream that has tormented me all my life. I am in a very small space behind a wall.

There is a tiny hole through which I can see into a room filled with shadows, some of them moving. The darkness is broken by a shard of light that fl ashes again and again. Blood pours from it, a giant

wave of blood lapping against the walls of the room and threatening to drown me. I wake to my own screams, which I have learned from long practice to muffl e in my pillows.

As quickly as I could, I clambered to my feet. My limbs shook and I could feel the hot wash of tears on my cheeks. Had anyone come in to see me in such a state? Was someone there now, waiting

in the shadows? The Spaniard had died not far from where I stood.

Did his spirit linger? Did my father's shade, unable to rest until I fulfilled my vow of vengeance?

Heart hammering, I lit the candle beside the bed but found no comfort in its meager circle of light. Beyond the tall windows, the moon rode high, casting a silver ribbon across the garden and far

beyond. Rome slept, so much as it ever did. In the narrow alleys and lanes, rats were at work, gnawing here, feasting there, noses twitching, claws grasping, all in the shadow of the Curia. I lifted my gaze, staring into the middle distance from which I fancied I could see, glowing in the silver light, vast, writhing tentacles stretching outward in all directions, grasping at power and glory through all of

Christendom. The vision was no more than a figment of an overwrought mind, yet it was real all the same. As real as the whispers that the master of it all, the Vicar of Christ on Earth, Il Papa Innocent

VIII was dying.

Of natural causes?

Do not tell me you are shocked. We live in the age of poison, of one kind or another. Every great house employs someone like myself for protection or, when necessary, to make an example of an enemy.

It is the way of things. The Throne of Saint Peter is hardly immune, being no more than the ultimate prize the families fight over like yapping dogs maddened at the kill. No one perched on it should

sleep too soundly. Or eat without having his food tasted first, but that is just my professional opinion.

Cui bono? If the Pope dies, who gains?

Still weary in body and mind, I pulled off my clothes and slipped at last into the bed. Hugging my knees, I felt the cool damask of the pillow beneath my cheek. Around me the palazzo slumbered and

shortly so did I, safe within the stronghold of the man who had plotted for decades to make the papacy the ultimate jewel in his earthly crown.

In the morning, I retrieved the clothes I had abandoned on the floor, smoothed the wrinkles from them, and folded them carefully away in the wardrobe. Mindful of the dignity of my new estate but

equally concerned with comfort on what promised to be a sultry day, I donned a simple white linen underdress and covered it with a blue overdress embroidered along the hem with a pastiche of flowers.

The embroidery was my own poor effort, for I have never been skilled with a needle; the fl owers were the deceptively benign blossoms found on various poisonous plants. So had I made more tolerable the tedium of stitchery, at which every decent woman is expected to excel regardless of her natural inclination.

Properly dressed and with my hair twined in a braid coiled around the crown of my head, I ignored the rumbling of my stomach and set about my newly acquired duties with what I hoped was a pardonable eagerness. Firstly, I sought out the captain of the condotierri to review the security precautions my father had put in place. Every scrap of food, every drop of liquid, every object that conceivably could come into contact with Il Cardinale or any of his family had to be provenced, vetted, and secured. That required the full cooperation of the captain of his guard.

Vittoro Romano was outside the armory in the wing of the palazzo that also housed the barracks. A dozen or so young guardsmen had dragged benches into the sun and were busy polishing their armor

while keeping an eye on the servant girls who found reason to pass by, balancing baskets of laundry or kitchen supplies on their swaying hips. Several cats dozed nearby, raising their heads only to stare

at the pigeons who stayed just out of reach. It had not rained in days. The sky held the lemony hue that comes to Rome in summer.

The courtyard in front of the armory was dusty, despite being paved with cobblestones. I watched an eddy of dirt spring up in the wake of a passing breeze and dance across the space of several yards before collapsing almost at Vittoro's booted feet.

He did not appear to notice. In his fi fties and of medium height with a saturnine temperament, the captain of the guard gave the impression of being neither very interested or even particularly aware

of what ever happened to be going on around him. Anyone foolish enough to be gulled by that deception could count himself fortunate if he lived long enough to regret it.

Vittoro was speaking with several of his lieutenants but sent them away when he saw me. I was apprehensive about approaching him, wondering how he would take to dealing with a young woman

who had killed to attain a position of authority. To my relief, he greeted me with a cordial nod.

"Buongiorno, Donna Francesca. I am pleased to see that you are well."

By which I gleaned that the Captain, at least, did not regret Il Cardinale's decision to let me live, as opposed to having my throat slit and my body tossed into the Tiber, or however he chose to dispose

of those who displeased him. Even so, I was under no illusion that the rest of the house hold felt the same. The old woman who had branded me a witch was unlikely to be alone in her sentiment.

I stood before him gravely, mindful that others were watching.

"Thank you, Capitano, and I you. If it is con ve nient, I would like to discuss our security procedures."

He sketched a small bow and straightened smiling. "By all means. Do you wish to make any changes?"

"To the contrary, I want to make sure that no one mistakes the trust Il Cardinale has placed in me as a license for laxity. Were that to occur, I would have no choice but to take it amiss."

"How amiss?" Vittoro inquired. I did not mistake the twinkle in his eye. He had known me as long as I had lived under Borgia's roof and had seen me grow from a gawky child to a somewhat less

gawky woman. He and his wife— a plumb, cheerful matron— had three daughters, all close to my own age. Being proper young women, each was married, but they all still lived in the neighborhood

with their husbands and growing broods of children. They were a source of great contentment to their father. I had seen my own look at them wistfully on their frequent, clamorous visits to the palazzo.

"Very amiss," I replied.

Vittoro nodded. "I will put that about. What ever anyone thinks of Il Cardinale's choice of you, no sensible person wants to be on the wrong side of a poisoner."

I allowed myself a small sigh of relief. His support was essential to my success and I was grateful for it. We went on to speak of the procedures that, thus far at least, had proven effective in safeguarding

Borgia and his family.

Over the years, numerous attempts had been made to kill or at least incapacitate Il Cardinale, but all had failed thanks to my father's vigilance. One such effort had involved a round of cheese injected

with a solution of arsenic. Another concerned a bolt of clothe tainted with tincture of thorn apple. There were others but I see no reason to detail them.

Of a certainty, there would be more. It was only a question of time before an attempt was made to test the vigilance of Borgia's new poisoner.

I knew that full well even as I lived in apprehension of it. "D'Marco is looking for you," Vittoro warned when we were done. I grimaced, to his amusement, and took my leave. My intent was

to make my presence felt in what was, from my perspective, the most vital part of the house hold and of necessity the essential focus of my attentions, the kitchens. I got as far as the covered walkway leading to them when I was intercepted by a small, ferretlike fellow.

Renaldo d'Marco was Borgia's steward, roundly disliked for his tendency to peer into every nook and cranny in search of wrongdoing.

A certain amount of skimming is a perquisite of employment in so august a house hold, but too much cannot be condoned lest it bankrupt the establishment and kill the golden goose. By at least

pretending to insist that there should be none, the steward managed to keep what did occur within tolerable limits.

He darted at me from out of the shadows hanging beneath the walkway. Such was his regard for his dignity that he wore a crimson velvet robe and matching cap despite the heat. He clutched a portable

writing desk to his meager chest, as though it would ward off what ever blows came his way.

Frowning, he said, "There you are, Donna Francesca. I have been looking all over for you. I must say I was surprised when I learned . . .but never mind, that is of no account now. You would have been

well advised to seek me out directly this morning and in the future,I hope you will do so. His Eminence trusts me in all things, I know his will and can be of great assistance to you."

Having no wish for his enmity, I answered mildly. "I will keep that in mind, Master d'Marco. For now, what do you seek?"

Mollified, the steward drew himself up a little straighter and informed me, "His Eminence has instructed that you are to inspect arrangements in the house hold of Madonna Adriana del Mila without delay for such purpose as to confi rm the safety and well-being of Madonna Lucrezia and others domiciled there. Further, I am instructed to give you this."

With palpable reluctance, he handed over a small pouch, which, I quickly determined, contained gold florins. I had handled money before; when I visited the markets with my father, he often gave me coin and instructed me to pay. As I grew older, he taught me the fine art of haggling and trusted me to get the best prices. I mention this so that you will understand I was not surprised to be given money,

only puzzled as to what I was to do with it.

"Your salary for this quarter of the year," Renaldo said. He turned the writing desk toward me. "Sign here."

I signed and was glad that my hand did not tremble. Of course, I had understood that I would be paid; I simply had not thought how much. My father had left a substantial amount of money on account

in a bank in Rome. It had become mine upon his death. With that and with the addition of my new income, I was that rarity of my age, a woman of independent means.

That suited me very well, as I refl ected when I had taken leave of Renaldo and, having returned to my quarters long enough to secure the greater portion of the fl orins in the puzzle chest, set off to do His

Eminence's bidding.

By his own standards, Il Cardinale was a man of discretion. As an example, he did not quarter his current mistress or any of his various children by his past mistress in his official residence on the Corso.

Instead, they were in the care of his cousin, con ve niently a widow of the powerful Orsini clan who lived in suitably noble circumstances nearby.

Since my father's death, I had not ventured beyond the palazzo, which, with its vast main building and surrounding dependencies inhabited by hundreds of servants, retainers, courtiers, and clerks, could be thought of as a miniature city. Just outside it lay the gracious square that Borgia viewed as an extension of his own domain, using it for all manner of crowd- pleasing entertainments from bullfights to pantomimes and fi rework shows. He had even gone so far as to renovate the other homes facing the piazza in order to raise the overall appearance to his own exacting standards.

Like his own monument to himself, the buildings were newly faced in travertine marble, brought from the nearby precincts of Tivoli. You see it everywhere in the city now— on bridges, churches, palazzi, even the windowsills of humbler homes and the curbstones of the newly paved streets. Should you visit Rome or be fortunate enough to reside within it, I recommend that you find occasion to rise early and observe how each new day transforms the city from the monochrome of night to the blushing hues that the sun draws from this remarkable stone. Later, you will see the colors deepen almost to purple before fi nally yielding late in the day to muted gold. It is said that Rome possesses the fairest palette of any city and I know of no reason to disagree.

As always, leaving the confi nes of the square for the larger city involved a brief sense of dislocation. Rome was in its usual perpetual turmoil. Everywhere I looked there were throngs of people, some on foot or on horse back, others in litters or carts and wagons, creating a cacophony of sound and a sea of motion that can be dizzying. Priests, merchants, peasants, soldiers, and wide- eyed visitors alike jockeyed for space in the streets and lanes. It was said that every language on earth could be heard there and I believed it. The healing a few decades before of the Great Schism that had torn the Church apart has restored Rome as the center of the Christian world. What had been a scruffy medieval town of haunted ruins and greatly diminished population was being transformed seemingly overnight into the greatest city in all of Europe.

Nothing better exemplifi ed Rome's rebirth than the grandiose palaces being built by the great families. While the towering palazzo of Il Cardinale, erected fi ttingly enough on the site of the old Roman mint, was the fi rst among them, the vast and luxurious Palazzo Orsini bid fair to be its rival. Indeed, it should be called the Palazzi Orsini for it comprises several palaces, built around a vast inner courtyard, with each belonging to a different— some would say rival— branch of the Orsini clan. My destination was the wing of the palace situated on a narrow street within sight of the Tiber.

Scarcely had I stepped into the blessedly cool marble entry hall and announced myself to the majordomo than I was assailed by a slender girl on the verge of womanhood whose heart- shaped face was framed by a riot of blond curls. This exquisite creature, smelling of violet with a hint of vanilla, threw herself at me and hugged me fiercely.

"I have been so worried about you! Why have you stayed away? I wept for you . . . for your beloved father . . . for you both! Why weren't you here?"

How to explain to the cherished only daughter of Il Cardinale why she had been so neglected? How to entreat her pardon?

"I am so sorry," I said, hugging the twelve- year- old. "I was not fit company, but I knew, truly I did, of your thoughts and prayers. From the bottom of my heart, I thank you."

So soothed, Lucrezia smiled, but her happiness faded as she beheld me. We had known each other virtually all of her young life. We shared the common bond of daughters loving and beloved of powerful, feared fathers. In the isolation that imposed, we had reached out to each other, fi nding a degree of sisterhood that comforted us both even as it could never erase the social gulf between us.

"You are too pale," Lucrezia declared. Though the younger by seven years, she did not hesitate to assert the authority bestowed by her superior position. "And you have lost weight, now you are too thin. And your hair, why must you always wear it in that braid? You have beautiful hair— such a lovely shade of auburn— you should let it down, the better to be admired."

I stepped back and smiled at her. "My hair is not beautiful and I am not seeking admirers, therefore I wear it up for practicality's sake."

Lucrezia's good humor fled as did her brief interest in my own troubles. With a pretty pout, she sighed. "Perhaps I should envy you. Have you heard?"

"Heard what?" I replied although I knew the answer already.

Not even grief for my father had shielded me from the gossip of the house hold. We linked arms as we walked from the entry hall toward the family quarters.

"A second betrothal broken! Another husband gone! What is my father thinking? He has promised me to two men, both fine upstanding lords, Spanish like ourselves, and then he changes his mind. I will die an old maid, I swear I will!"

"You will be gloriously wed and your husband will cherish you forever."

"Do you really think so?"

Did I? That Il Cardinale would arrange the most magnificent marriage possible for his only daughter could not be in doubt.

Everything he did served but one purpose: the greater glory of La Famiglia. Perhaps he truly believed that through the advancement of the Borgias would come good for the Church and all of Christendom.

Perhaps he did not care a whit. No matter, the benefit of La Famiglia directed all his actions. As to whether that would result in any personal happiness for Lucrezia, who could know?

"It will be as God wills," I said. "Now I must speak with Madonna Adriana. Will you come with me?"

We chatted as we walked through the galleries fi lled with statues, some new, some recently reclaimed from the excavations going on throughout the city. Along the way, I tried to gauge if Lucrezia had any sense of the change the past day had wrought in my own circumstances.

The younger girl made no mention of that as she prattled on cheerfully. Child though she still was in many ways, the Cardinal's daughter was skilled beyond her years in keeping her own counsel. It was impossible to be completely sure of what she knew or how she knew it.

At last we came to the wing of the palace occupied by Il Cardinale's house hold. The guard standing before the entrance bowed as we passed through the high, bronze gates. Beyond lay a world of splashing fountains, scented gardens, silk boudoirs, and gilded assembly rooms so utterly feminine that I thought of it as il harem. Where the Cardinal, prince of the Holy Roman Church, one of the most powerful men in all of Christendom, came to throw off the cares of his day and accept the comfort of his women.

And such women they were. Besides the sweet vivacity of his only daughter, he enjoyed the company of his cousin, Madonna Adriana de Mila, widow of the late Lord of Bassanello and a power to be reckoned with in her own right. Among her countless virtues practicality reigned supreme. So sensible was her nature that Madonna Adriana offered no objection when Il Cardinale took as his mistress the astounding Giulia Farnese, Giulia La Bella as she was called, said to be the loveliest woman in all of Italy, if not the world.

That she was also the wife of Adriana's stepson might have prompted some objection from the older woman. Instead, La Famiglia ruled, as always. Adriana agreed to the removal of her stepson to his country estate, leaving the sixty-one-year-old cardinal free to enjoy the charms of eighteen-year-old Giulia, who was herself happy enough to acquiesce.

Both women were enjoying the shade of the inner garden, seated beneath a plane tree, sipping chilled lemonade and watching the antics of a pair of fluffy Maltese pups at play in the grass before them. Blackamoors in pearl- trimmed turbans and silk pantaloons stood behind the ladies, fanning them with braces of pure white ostrich feathers.

Lucrezia darted forward, laughing as she fell in a heap on the bench beside Giulia and called for a cold drink. I hung back, waiting to be acknowledged. Madonna Adriana eyed me for a long moment before she raised a bejeweled hand and gestured to the stool at her feet.

"No need for such formality, cara. Sit, tell us your news."

I did as I was bid, smoothing my skirts as I murmured, "Grazie, Madonna."

"Such a warm day," Giulia said. She arched her slender neck and stretched languidly. "I can scarcely keep my eyes open." No surprise there, as rumor had it she was with child. The Cardinal was said to be pleased. He had I don't know how many children by various mistresses, but there was no doubt that he had his favorites. Likely La Bella's would be another of them.

I stared at Giulia in unwilling fascination. She truly was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen. Some combination of golden hair, dark eyes, perfectly harmonious features and a manner at once warm yet aloof compounded to create within her an aura of sensual and spiritual perfection. The latter was entirely misplaced but as for the former . . . perhaps only Il Cardinale could truly judge.

For all that, she was not without a brain.

"How clever of His Grace," Giulia said, looking at me. "How daring. I had no idea he believed women capable of such responsibility."

So they did know. Good, that made everything simpler.

"His Grace," I said, "is, as always, infi nitely wise and just."

The two women murmured their agreement in the way of prayers reflexively intoned. Lucrezia merely watched, eyes darting from one to the other.

"But surely we have nothing to fear here," Adriana ventured with a glance around the garden nestled within sheltering walls.

"Of course not," I said quickly. "I only wish to make certain that everything is as it should be."

"For which we

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...