- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

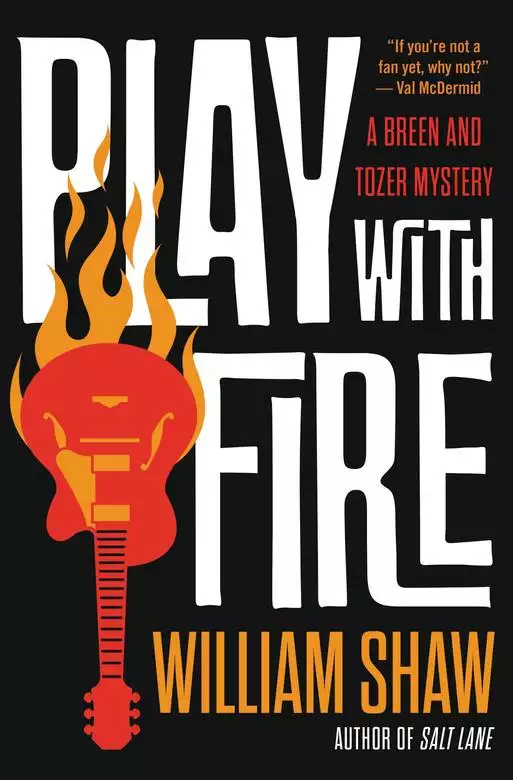

Synopsis

In hedonistic 1960s London, a police detective investigates the unexpected connections between two suspicious deaths: a call girl and a rock star. In the summer of '69, the hard-living rockers of the British Invasion still rule London when former Rolling Stone Brian Jones is found floating in the pool of his palatial home. On a quiet residential block that should be far removed from the swinging party scene, Detective Sergeant Cathal Breen investigates the murder of a young woman. But the victim, known professionally as Julie Teenager, was a call girl for the rich and famous. Her client list is long, and thick with suspects-all rich, powerful, and protected. As DS Breen hones in on his prime target, he receives a pointed warning: Watch your back. Fortunately, Breen doesn't have to work alone. His keenly intuitive, deeply moral partner Helen Tozer, despite the pregnancy that's interrupted her policing career, can't help being drawn into the case of a girl used and cast aside. Tense and dramatic, unfolding at a blistering pace, Play With Fire is a gripping police thriller set in the darkly technicolor world of the 1960s.

Release date: August 13, 2019

Publisher: Mulholland Books

Print pages: 449

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Play with Fire

William Shaw

A gentle mist rises from the water into the dark air.

It is approaching midnight; moths fuss around the blaring bulbs that light the way to his home, a red-tiled sixteenth-century farmhouse that squats like a toad crouching in the rolling hills on the edges of the Weald. The garden is lush, though a little unkempt now. The high hedges need cutting; the shrubs have outgrown their beds.

This is the house of a rich young man; a rock star.

A trail of wet footprints leads along the stone path towards the building. Through an open bedroom window on the first floor, comes the sound of a telephone. The metallic trill is interrupted by a woman’s voice; ‘Hello? Oh hi. No. I don’t know where Brian is. Brian?’

It is his young pretty girlfriend. She calls from the room above. There is no answer.

‘He’s in the pool, I think. Yeah. I’m fine. Just hanging around, you know?’ A sing-song voice with a slight Swedish accent. ‘Brian? He’s kind of stoned, I guess. Am I stoned? A little bit.’ A giggle.

Another woman, blonde, emerges from the house while the other still talks. She is beautiful too, because this is a house where lovely women come and go. Even though the star is fading for the man in the pool, the women still come. He is a rock guitarist. Right now, there is nothing cooler. Often there are parties and loud music played on reel-to-reel tape recorders through massive loudspeakers.

The neighbours who live in the lanes around here are nervous; they are trying to keep up with the times, to be tolerant of the youngsters who arrive in cars and taxis, in Bentleys and on motorbikes, but these rich young people are changing their quiet hillside. On the nights where the music and shouting and revving engines continue late into the night, the locals lie awake in bed unable to sleep.

Tonight, though, is quiet. The rock star has been drinking and taking pills. No more than usual. Less, probably, in fact. He is tired and worn, weary of everything. The buttons of his shirts strain at the belly; his trousers are too tight. His band don’t want him any more. Sometimes he cries and hugs the women who come here.

Though there is a Rolls-Royce sitting in the garage, undriven for weeks, he has spent all his money. He’s never been sure where it all came from; now he doesn’t understand where it’s all gone. The building work on the second living room is unfinished and the builders are asking for payment.

The woman approaches the pool looking for towels. Men just leave them lying anywhere. They expect the women to clear up after them. It’s not fair.

She can hear the rock star’s girlfriend upstairs, still talking on the phone. For a second, she wonders where the young man who owns the house has gone. She looks around. The pool is so silent; the water is still, lights from the house moving gently across the surface.

Besides a discarded towel and the empty glass of brandy sitting by the side of the pool, the place seems deserted. She picks up the towel and looks around again.

And sees him.

Under the water, he hangs, arms splayed out, inches from the bottom of the pool. He is like a diver in mid arc, except he is still, and beneath the surface, not above it. She looks harder. At first she thinks he’s playing, but the water is too still.

Time seems to slow.

She runs back up the path and shouts and screams below the open bedroom window. It seems so long before anyone hears her.

And so much longer before the police finally arrive and see the body, skin like white rubber, pale and cooling, laid on the limestone paving at the pool’s side.

‘Bloody hell,’ says a sergeant, tired at the end of his shift. It will be a long night.

Neighbours sit up in bed, unable to sleep again for the noise. But it will be much quieter here now, at least.

London; a summer evening.

Though she didn’t live here, the middle-aged woman had her own key to the house; she let herself in. She was smartly dressed, a dab of Yardley on her décolletage. Looking at her, nobody would guess what her job was. That’s the way she preferred it. None of her neighbours knew. She liked to imagine they assumed she was some rich bohemian living off her inheritance. They would be shocked if they knew.

Today was Friday. She was annoyed because she had left it too late to go to the bank and they all closed at three and wouldn’t open again until Monday morning. It was OK. Lena would advance her a tenner to tide her over, but she didn’t like to borrow. She was a professional.

She pressed the lift button and waited for the whirr of machinery. There was no sound.

It was one of the rickety, old-fashioned ones, with a criss-cross metal scissor gate. She tried the ‘Up’ button again, and once more.

‘Hell.’

‘Broken.’ A voice behind her made her jump.

She turned. Mr Payne, the old man from Flat 1, was at his door. He seemed to lurk there, waiting for someone to talk to.

‘Hasn’t been working all day.’

‘Hell’s bells.’ Now, every time a customer rang the doorbell she would have to traipse down two floors, and all the way back up again. With her knees.

‘You’ll have to stay down here with me.’

‘Get lost.’ She smiled at him. ‘You pervert.’ Pathetic, the way she enjoyed flirting with men more as each year passed, even the ones old enough to be her father. Once, she had lived off her looks. She looked up the steep stairs.

In younger days, when she had been slimmer and the cigarettes had not coated her lungs, two flights would have been easy, but she found on this summer evening, she was sweating by the time she reached the second floor.

She knocked on the door, as she always did, but opened it with her key.

‘Hello? Only me,’ she sing-songed, as she always did, but today there was no answer.

‘Lena?’

The rest of the house was ordinary. The stairwell was drab. It was only when you went through the front door to Lena’s flat that everything changed.

She didn’t like her employer much, but she had to admit it; she had a kind of genius.

Pink. Everywhere. The walls, the curtains, even the lampshades, were a rich girlish colour. The carpet, at least, was white. The beanbag, a shocking lime green. There was a framed picture of The Beatles on the wall, not as they were now, bearded, dissolute and immersed in Eastern philosophies, but when they were still neat, uncomplicated and joyful, and when every teenager loved them.

Everything had been picked with care. The pop group grinned, wearing pink shirts and ties and holding red roses. Other less famous stars surrounded them, some cut out from Rave and Jackie and stuck up with Sellotape, others framed and signed in black pen. Across the world, teenage walls looked like this now. Lena had invested in the place.

It was perfect, down to the collection of dolls and gollywogs, lined up on a bookshelf, which Florence hated. It wasn’t just their unclosing stare that was creepy.

She looked around her and sighed. Most days Lena tidied up for herself. But there were rare times when she finished late and crawled into her bed, exhausted. Last night must have been one of them.

The teddy bear was on the floor, face down. The ashtray was full of cigarette ends, there were half-empty glasses on the table and an empty champagne bottle on the carpet.

Today was a Friday; the busiest night of the week. The first clients would arrive soon, after work. Everything had to be ready.

‘Lena?’ she called.

Still no answer.

Strange. She must have gone out. Florence checked her watch. The first customer would be here in half an hour.

She stuck out her tongue, threw open the window to get last night’s stink of smoke, alcohol and whatever else out of the room. She picked up the stuffed toy, wrinkling her nose at him, plumped the sofa cushions, and then sat him in his usual place.

Someone had been using the record player and had not put the records back in their sleeves. There was a disc on the turntable and a single just lying on the carpet: ‘Sugar, Sugar’ by The Archies.

Lena was not normally this slovenly, but someone had been having a nice time. It looked that way, anyway. Who was the last one in yesterday? The man who always brought children’s toys. Florence shuddered. So it wouldn’t have been a social occasion. And though she went out to parties sometimes with the in-crowd, Lena never had friends over. In fact, she doubted Lena had any friends. If she did, she never talked about them.

The single rose in a vase had shed onto the polished wood, next to the bottle. She picked up the loose yellow petals and scrunched them hard in her hand until the colour stained her skin. The bowl of sherbet lemons had been spilled on the floor too. Someone had trodden one into the white carpet. Florence knelt down and started to pick pieces out of the pile.

She had almost all the bits, cupping them in her left hand, when the black phone began ringing. Lena had two telephones. The ivory one for personal, and the black one for business. This was the business phone.

Florence sighed and straightened, painfully. She was too old to be scrabbling around on her knees. She brushed the broken sweet off her hand into the litter bin under the mock Louis Quinze desk, then picked up the handset.

‘Julie Teenager’s apartment.’ Her posh voice.

Many of the men were hesitant on the phone. You had to be patient with them; try and make them think all this stuff was normal, else you’d scare them off. This one wasn’t shy though. She recognised his voice; one of the regulars. It was one of the men who called himself Smith. There were a few. This was the large one, the married man who bit the nails of his left hand. She opened the appointment book.

‘Sorry, Mr Smith. Nine o’clock is all booked up, I’m afraid.’

In the appointment book, each week had two pages, split into five days. Sundays to Wednesdays, Lena didn’t work. The remaining three days were divided into four two-hour slots, starting at 5 p.m. and ending at 1 a.m.

‘You’re usually Thursdays, aren’t you? We had been expecting you. Nothing the matter I hope? Is eleven tonight too late?’

Yes, eleven was too late, Mr Smith said, sounding annoyed. He had to be on the train home by then.

‘Oh, what a shame, Mr Smith,’ said Florence. ‘Julie will be ever so disappointed. She always looks forward to your visits.’ She smiled as she talked to him; a good impression was always important. ‘Perhaps you would like to make a date for next week?’

She entered his name into the appointment book, closed it and looked around her, sighed.

The bedroom was worse. The bed was unmade, the ashtray spilled onto the carpet and Lena had left knickers on the floor. She was normally such a good girl, too. The school uniform, at least, was folded up neatly on the chair.

She put the dirty knickers into the bin and was about to close the bedside cabinet drawer, which was half open, when she saw a handful of pound notes stuffed in there. Honestly. Careless. Florence peeled off ten. She shouldn’t have to be doing this work anyway.

Then she looked at her watch. It was twenty to five already. Where did all the time go? And, for that matter, where was Lena? She went back and checked the appointment book. Her first customer was due at five. Another regular. Another Mr Smith. This one was an elderly gentleman, rich and well-connected, but a poor tipper, like all his sort.

She took the empty bottle downstairs with the rubbish and paused on the first floor to catch her breath. The students in Flat 3 had left their door open to let the air circulate. Peeking through the door, she spied a young girl, dressed in only a red T-shirt and a small pair of knickers, standing in the living room smoking a cigarette. It was the pretty one. All the boys who shared the apartment would be in love with her. She scowled and set off up the next flight.

She left the bathroom till last. She was surprised to notice blood in the toilet. It lay as a layer in the curve at the bottom of the bowl, vivid against the white. Unusual. It wasn’t Lena’s period. She knew that for a fact. They didn’t work when it was.

She peered at the red blood for a while, frowning, then flushed the cistern. She looked at her watch again. Where the hell was she?

At five, exactly, the bell rang. The flat was tidy at least. But Lena was still not back.

The man arrived, panting from the climb, and sat on the couch next to the enormous teddy bear. He had brought a present, wrapped in white paper and tied with a big red ribbon. ‘Would you like a cup of tea while you wait?’ Florence asked him, looking at the red against the white and starting to feel as if something was not right. ‘Or something stronger perhaps?’

‘Bloody lift,’ he said, catching his breath. ‘Not working.’

Maybe it was a good thing Lena wasn’t here. The man didn’t look like he’d survive an hour with Julie Teenager anyway.

It was Saturday morning; Detective Sergeant Cathal Breen of the Metropolitan Police’s D Division had just put on the first pair of jeans he had ever owned when the doorbell rang.

He opened the door only a little way. Elfie was standing on the doorstep, holding a cake. ‘It’s just so sad,’ she said.

‘What is?’ called his girlfriend Helen from the living room.

In front of her pregnant belly, the young woman Elfie, who lived upstairs from them, held out the hot cake tin. ‘This is. Look at it. I made it for us to take to the concert, but it’s rubbish.’

Their neighbour was wearing a brightly printed muslin dress that you could see her underwear through. And oven gloves. ‘Do you have icing sugar? I was thinking I could fill in the dip with it. Aren’t you two ready yet? No point being late. We’ll never get in.’ She looked down. ‘New trousers, Paddy?’

Cathal Breen’s father had been Irish. Cathal had never asked to be called Paddy but the name had stuck. He looked down at his jeans. He was a policeman, unused to trousers without creases; in the Met, only the Drug Squad wore jeans. ‘Seriously. What do you think?’ he asked. ‘Are they OK?’

‘Icing sugar?’ called Helen from the living room. ‘Will ordinary sugar do?’

Breen was never sure whether his girlfriend Helen was just winding Elfie up, or she genuinely didn’t know this stuff. Elfie pushed past him into his flat where Helen was sitting in Breen’s armchair eating biscuits straight from the packet.

Though they were both due in the next few weeks, Elfie’s bump was huge; Helen’s looked ridiculously small. They were both pregnant. Obviously he was glad the two women had become such close friends; he worked long hours. Who wouldn’t be glad? It was convenient that Helen had company when he was on duty. But while Helen was a former policewoman, Elfie had never worked in her life. She was a hippie who lived with a man who drove an ancient sports car, who had some job in advertising in Soho. There were days when he wished he could spend more time with Helen, on her own.

‘It’s carrot cake,’ said Elfie. ‘I made real lemonade too. For the picnic.’

Helen spat biscuit crumbs. ‘You can’t make cake out of carrots.’

‘You’re not even dressed yet, Hel. We’ve got to get there in plenty of time because it’ll be super-crammed and we’ll probably have to walk from Oxford Circus.’

‘We’ll just push our way to the front,’ said Helen. ‘Make way. Two pregnant ladies.’

They laughed. Sergeant Cathal Breen stood there listening to the two women, still looking down at his new pair of trousers. They weren’t very flared at all, really, but he worried that they looked stupid on a man his age. Jeans were for young people. They’d look fine on Helen because she was eight years his junior. He’d bought a pair of dark glasses too.

‘What do you think of the trousers, Elfie?’

‘Do you like them, Paddy?’

‘That wasn’t what I asked.’

‘Just be yourself, for once, Paddy. Not “The Man”. Just be who you want to be. Come on, Hel. We’ll miss it if you don’t come now.’

He scowled at her, but she was right. The world was changing; he should change too. He would go to a rock concert. He would enjoy himself. It would be great, wouldn’t it?

‘Anyway, we can’t leave yet. We’re waiting for Amy,’ said Helen, stretching the skin at the bottom of her left eye as she put mascara on in the mirror. Amy was another girl friend. Breen had grown up motherless, raised by his Irish father. All his working life had been around men. Now, it seemed, he was surrounded by women. He was not used to it.

‘Is she coming with us?’

‘Course.’

Amy arrived in a white men’s collarless shirt and denim shorts. ‘Where from?’ demanded Elfie.

‘Portobello Market. Second-hand.’

‘You are so cool,’ said Elfie. ‘Seriously cool.’

Amy kept her hair short and wore her eye make-up thick. Where Breen’s girlfriend Helen was angular and lanky-limbed, Amy was round-faced and her skin shone; she could pass for a model, even in a dead man’s shirt.

As they walked to the bus stop, Breen tried the dark glasses on and ran his hand through his hair. It was getting too long. He should have it cut.

At Tottenham Court Road, from the top deck of the bus, they started to notice the change. It wasn’t the usual Saturday crowd with prams and bags.

From all around, the young people were gathering. They carried backpacks, blankets and guitars slung over shoulders. The men wore T-shirts or had their shirts hanging out of the trousers. There was paisley, tartan, leather, embroidered sheepskin. A woman walked barefoot, not caring how dirty she became. On the news they’d shown hundreds of them sleeping overnight in the park so that they could keep a space at the front of the stage.

At Bourne and Hollingsworth, the crowd of shoppers parted. Two men, dressed in black and wearing Nazi helmets, strode west towards Hyde Park. People stared. The men pretended not to notice.

Elfie and Helen were at the front of the bus; he was sitting with Amy, just behind them, with Elfie’s hamper, full of sandwiches, cake and thermoses, on his lap.

‘I bet you don’t even like the Stones,’ said Amy.

‘Loathe them,’ said Breen. ‘The drummer’s OK, suppose.’

‘I adore them,’ said Amy. ‘They’re beautiful.’

At Oxford Circus they got off the bus and started to walk through the throng; the closer they got, the thicker the crowd became.

Ahead of them, someone was blowing bubbles. Against the blue sky, they drifted above the heads of the hippies. Amy took the Super 8 movie camera she carried everywhere out of her bag and pointed it at them.

As she filmed them, beautiful people posed and pouted, laughed and waved.

‘Christ,’ Breen said aloud as they crossed Park Lane. As far as he could see, there were people. Some were sitting on the grass, some were perched in the branches of the trees, some were handing out pamphlets, others playing guitar or dancing.

There was a war going on; old versus young. Here the young were winning. Other places, not so much. Last year the Soviet tanks had moved into Czechoslovakia. In Poland, they had come down hard on the student strikes. There had been concerts here in the park before, but nothing anywhere near as big as this.

‘Go on, say it,’ said Helen.

‘No. It’s great,’ he said.

She grinned at him. To be fair, it wasn’t that he resented young people having fun, just because his generation had never had anything like it; it was that so many people in one place made him nervous.

Helen understood that. She reached out and took his hand. Keep calm. You’re not a copper today. He squeezed her hand back. Wherever Elfie and Amy saw peace and transcendence, he saw potential for crime and disaster. That’s what the job did to you. Helen would know what he had been thinking, because she had been a policewoman too, once, working alongside him before she became pregnant.

And then the thick, oily scent came. People were smoking drugs; it was blatant.

‘You’re not on duty,’ said Helen. ‘Leave it.’

‘Didn’t say anything.’

‘What are you two lovers whispering about?’ said Elfie.

‘Nothing.’

It’s why Amy’s boyfriend John Carmichael wouldn’t come, even though Amy had asked him to. He was Drug Squad, jeans and all.

A uniformed copper was trying to keep people out of the road. He grinned. ‘Hiya, Sarge.’

Breen recognised a young thick-necked constable from D Division, working overtime. ‘What are you doing here, with this bloody lot, Sarge?’

For a second, Breen felt like a schoolboy caught bunking off. He was about to speak when Helen raised her finger to her lips and looked from left to right. ‘Shh. He’s undercover.’

‘God, sir. Sorry. Didn’t realise.’

‘Carry on, Constable,’ said Breen, and winked at him.

Helen was giggling; she looked around for Elfie who had disappeared into the crowd. Breen spotted her beckoning to them. ‘Over here!’

She was holding hands with a big man who wore a baseball jacket and Michael Caine glasses. Like Breen, he was older than most people around him. With his free hand he was rubbing her large belly. ‘How long till the baby, Elfie?’

Elfie grinned. ‘This is Tom,’ she announced loudly enough for everyone to hear. ‘Tom Keylock. He works with the Stones.’

‘Don’t tell everybody. Christ sake, woman. Can’t stop though, Elfie. I’m mad bloody busy.’

‘Can you get us somewhere where we can see it properly, Tom? This is my best friend Hel. She’s pregnant too. Please, Tom.’

‘Bloody hell,’ said Tom. ‘Always the bloody chancer, Elfie.’

‘Please, Tom. Pretty please?’

He rolled his eyes and grinned. ‘Come on then, girls.’

Now Elfie was tugging Helen through the crowd, past loud activists with manifestos, and earnest hippies sitting cross-legged on the grass, past young women in cut-off jeans, revelling in the easy power of beauty, past the saucer-eyed man giggling to himself, towards the stage at the middle of the park.

The Hell’s Angels were doing security. A young, pale-haired biker was turning people away from the back-stage area. Only a few, presumably those who knew some secret password, were admitted. It was funny, thought Breen, how a generation that hated the police so unthinkingly let these swastika’d bullies take their place. Helen must have noticed the look on Breen’s face because she said, ‘Don’t. OK?’

‘I didn’t say anything.’

‘They’re cool,’ Tom insisted to the man on security, and the Hell’s Angel stood aside, moving as slowly as he could, as if to show his contempt for anyone so straight.

They had made it into a small, fenced area by the side of the stage. Elfie laid out the blanket and opened the basket. ‘Ta-da!’ she said. ‘Best seat in the house.’

‘Got to run,’ said Tom, kissing Elfie on the cheek. ‘Be good, darling. Love to Klaus.’ Elfie’s boyfriend.

Breen was holding out his hand to say thank you to the man when Elfie asked, ‘What about Brian? Were you there?’

Tom’s smile vanished. ‘Not when it happened. No.’

‘They’re saying he committed suicide.’

‘Got to go,’ Tom said again, quietly, and pulled away.

‘You can’t actually see the band from here,’ Helen was complaining as she tried to peer past a palm tree that had been placed by the improvised stairs up to the temporary stage.

Elfie didn’t seem to hear. ‘I think it’s sad,’ she said.

‘Are you still on about the cake?’ asked Helen.

‘No. Brian Jones.’

‘He drowned,’ said Helen. ‘That’s what it said in yesterday’s paper.’

‘Never believe what you read in the papers,’ said Elfie, opening a bottle of beer and passing it to Breen. ‘Everybody is saying he was distraught because they’d kicked him out of the Stones. It was his group, after all.’

A band started playing on stage, but it wasn’t the one most people had come to see. Nobody paid them much attention.

‘Didn’t your boyfriend arrest Brian Jones last year?’ said Helen.

‘Did he?’ said Amy. ‘Nothing would surprise me.’

Breen shook his head. ‘It was before his time.’ John Carmichael was Breen’s oldest friend; they had been at school together, signed up for the force together. ‘That was long before he joined the Drug Squad. He was still working with me on D Division.’

‘Bloody shut up, you,’ whispered Elfie. ‘If they find out you’re a copper I’ll never live it down.’

‘What happened to “Just be yourself, Paddy”?’ said Breen.

‘Just don’t be a policeman, OK? I don’t know why you’re here. You don’t even like rock music. First time I ever met you was when you called through our letter box telling us to turn down our moronic racket,’ said Elfie.

Helen laughed. Breen smiled at her. ‘It was loud.’

‘Nothing like this!’ She pointed at the massive stacks of speakers, piled on scaffolding in front of the stage.

‘He’s a dinosaur,’ said Helen. ‘He still wears a string vest. At least John doesn’t wear old man clothes.’

Amy wrinkled her nose.

‘What’s wrong?’

‘I think we’re splitting up, me and John.’

‘No,’ said Helen.

‘He never asks me out any more. Every time we’re supposed to meet he calls up with some excuse.’

‘He’s a policeman. You know how it is.’

Amy lifted her camera again and held it to her eye, looking through it, though she didn’t press the shutter release. ‘I don’t care,’ she said.

From behind the barrier, people stared at them in the enclosure, trying to work out if they were celebrities or not. It was a strange feeling. Elfie was clearly enjoying it, flinging her arms around Helen as someone from the crowd photographed them.

It was a free concert and it looked like everyone in London who was under thirty was there. Just ordinary people, having fun. What was wrong with that? thought Breen.

‘I bet he’s here somewhere,’ said Helen, looking around. ‘Big John. Sniffing around with his Drug Squad mates. They can’t resist something like this.’

‘It’s his job,’ said Breen.

‘Be ironic if he arrested one of us,’ said Elfie.

‘It wouldn’t be the first time,’ said Amy, with a sad smile. ‘That’s how we met. He busted our cinema.’

Elfie thought this was hilarious, even though she’d heard the story before. Amy worked at the Imperial in Portobello Road where the air at the late night screenings was often thick with pot smoke.

‘He hates the Stones. Only likes bloody jazz. Like Cathal. Anyway, who’s saying what about Brian Jones?’ asked Helen.

‘What if he was killed?’ said Elfie.

‘Who?’

‘Brian Jones. Tom worked with Brian. He says they kicked him out of the band. What if…’

‘Don’t talk rubbish,’ said Helen.

Elfie was handing out sandwiches. She’d made dozens. ‘I’m not the only one saying it, Hel. Bloody hell. Don’t look. It’s Keith bloody Moon.’

Helen turned. ‘Where?’

‘I bloody love him.’

They watched Keith Moon passing around a bottle of wine which people were swigging from, until a man carrying four large cardboard boxes, one piled on top of the other, blocked their view. The boxes seemed to be extraordinarily light from the way he carried them. With the help of a lanky man in a cotton shirt, he stacked them up by the side of the enclosure, ten feet away from them.

Tom Keylock returned. ‘That them?’ he was asking. ‘Sure they’re still alive?’

‘Don’t ask me. Open them and find out. Where do they want them?’

‘Put them on stage when they go on.’

Helen called over, ‘What’s in them?’

‘Butterflies.’

‘Butterflies?’

‘Don’t ask me,’ said Tom.

Elfie had spotted someone else she recognised in the crowd. ‘Hey, come and join us,’ she called, waving at a dreamy young girl with long dark hair. The girl looked up, smiled shyly, gave a little wave back, then looked down again.

‘Who’s that?’

‘She’s going out with Eric Clapton,’ said Elfie.

‘Never,’ said Amy. ‘She doesn’t look old enough.’

‘Seventeen,’ said Elfie.

‘How old’s he?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Look,’ said Helen, suddenly excited. Dropping her food, she pushed herself up off the grass.

A little way off, a crowd of photographers were snapping eagerly. A couple of men were walking towards the stage. Both were dressed in long, untucked shirts. The one with the blue shirt paused to sign a piece of paper for someone.

‘I can’t believe I’m backstage with the Rolling bloody Stones,’ said Helen, grinning like a. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...