- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

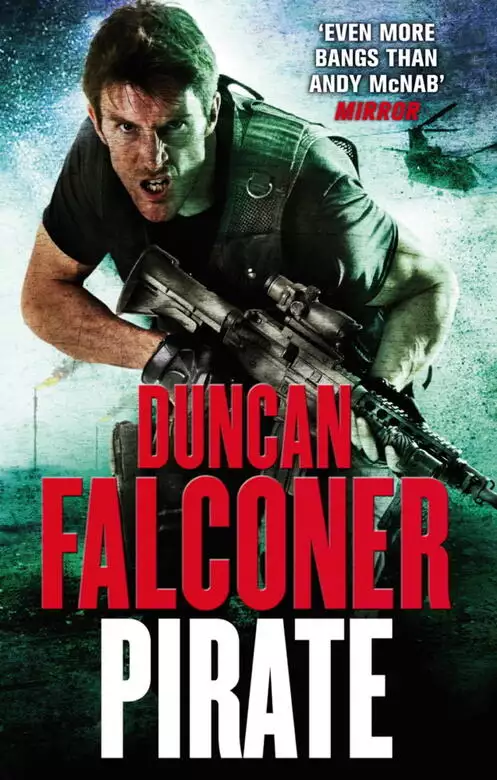

Synopsis

When elite operative John Stratton is sent to Yemen by the Secret Intelligence Service to track down a suspected al-Qaeda cell, he thinks he knows what he is dealing with.

But when he and his colleagues get captured by Somali pirates, all bets are off. Stratton discovers what it is like to be held hostage by ruthless men who have a deadly agenda - men for whom Stratton and his colleagues are just bargaining chips. And this is no ordinary hostage situation: Stratton has stepped right into the middle of a massive and sickening jihadist operation.

Fighting trained warriors who know no fear, Stratton's skill and ingenuity will be tested as never before as he battles for his life and for the values he holds dear...

Release date: June 23, 2011

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Pirate

Duncan Falconer

He first arrived in the Colombian capital on vacation: or at least that was the way his leaders wanted it to look. In reality

he was there to carry out a preliminary assessment of the city. And to ascertain what he needed to do to be able to apply

for a resident’s visa. Yusef was a tall, handsome and athletic man in his late twenties, and he was well educated, having

attended university in Barcelona, where he had lived for fifteen years. He’d been born and grown up in a small town on the

Kashmir border in Pakistan. But a wealthy uncle living in Spain had adopted Dinaal and brought the boy to live with him after

his mother and father, a policeman, had been killed in a dawn raid by the Indian army.

In the second week of Dinaal’s month-long visit to Bogota he met a young local girl. He frequented the street café where she

waited on tables. After just a few days he’d charmed her, completely turned her head. It had been easy enough for a man of

his looks and intelligence to convince the girl, who had left her village only a few months before to find work in the city.

It was almost as easy convincing her parents. After a brief but passionate affair, he flew back to Spain promising to return

to marry her. Three months later he was as good as his word.

It was a union of love for the Colombian only. For Dinaal, it was one of convenience. It meant he acquired his permanent resident

visa. And completed the first stage of his assignment. Dinaal had been sent to Colombia to set up an undercover operations cell. So he needed to be married. It was a necessary tool. It

allowed him to stay in the country for as long as he wanted and to travel abroad at will and return at will. Without having

to deal with the usual visitor’s visa complications.

He waited a year before he travelled out of Colombia. Dinaal went back to Pakistan for the first time since his youth. On

arrival he took the first of many trips into Afghanistan to meet his bosses. These visits, mostly into Kandahar, never showed

on the pages of his passport. Because he was always guided in and out through the mountainous, arid borders by people who

knew how to avoid Pakistani troop patrols and Western Coalition forces.

It took close to three years to get the Bogota active unit numbers up to operational strength. The secret cell was made up

of six other men, all of whom had been recruited from madrassas in various parts of the world that taught an extreme form

of Islamic jihad. The seven men had subsequently attended jihadist training camps once a year for weeks at a time, and on

one occasion for two hard months straight. They’d learned the art of terrorism. They’d taken weapons and explosives training

and been drilled relentlessly on how to conduct themselves undercover. Only one of the men was a native Colombian. The others

were from Pakistan, Indonesia and Saudi Arabia. In the final weeks of training they’d focused on the skills required to conduct

independent and unsupported attacks in foreign countries. By now they had solid small arms skills. They could handle pistols

and assault rifles. At this point they learned how to construct simple but lethal explosive devices using locally purchased

materials.

When Dinaal was sent to Colombia to set up the active service unit, the leaders didn’t tell him why. He would have to wait

another two years before learning of its purpose. But he had been able to wait because he was a patient man.

In truth, the men who had recruited and sent Dinaal to Bogota didn’t know what the task would be either. They were following

a directive that came down from on high. They had been ordered to set up as many active service cells as possible in just

about every significant country in the world. The cells were to remain asleep until given orders to become operational.

It was during one of Dinaal’s visits to Islamabad, while receiving training in the use of wire-guided missiles and anti-vehicle

mines, that he got called to attend a meeting. The gathering, which included other cell commanders, was held on a country

estate a few miles inside Afghanistan on the Kandahar road beyond the Spin Boldak border checkpoint. Much to his surprise,

Dinaal’s bosses were men he had never seen before. It was like there had been a complete changing of the command guard. Many

of the new leaders were younger than their predecessors and were far more politically savvy. They were also ruthless and ambitious.

The meeting lasted a whole day. One by one the cell commanders were called to give account of their units. When it came to

Dinaal’s turn, he described his men, their enthusiasm and their eagerness to do anything they were asked in the name of Islam.

He also emphasised they were all willing to die for the cause. At the end of it, Dinaal was given what seemed a strange sequence

of instructions. But he was not permitted to question them nor to divulge them to any living person outside the members of

his cell.

On his return to Bogota, Dinaal assembled his team at the first opportunity and relayed the instructions. His men were equally

bemused. He assured them that ultimately it would lead to a significant task: all he could say was that they were taking part

in a truly global operation, one that would have a greater impact than the Twin Towers assault on 11 September 2001. Dinaal

also warned the six men not to ask questions about the task nor to discuss any aspect of it beyond the walls of the secret

cell headquarters. He didn’t lie to them: if they disobeyed the order they would be killed.

The Colombian, the Indonesian, the two Pakistanis and the two Saudis assumed Dinaal knew the real purpose behind the weird

task. He did not let them think otherwise. He was well aware that information was power and that if you didn’t have any, it

was always best to let others think that you did.

He spent a week carrying out day and night reconnaissance of the target area on his own. He looked at it from every position

until he was satisfied. When he had decided on the location and timing, he took his two best men out on the ground to explain

the plan in detail. He showed them where it would take place and precisely how they would carry it out.

He had one relatively minor obstacle in the preliminary plan: the procurement of a rifle. Dinaal wasn’t worried about ammunition

being a major issue since he required only one bullet. And getting hold of a rifle was easy enough in Colombia. But it had

been impressed upon him that the acquisition of the firearm had to be as clinical as every other part of the operation. It

had to be a clean weapon, untraceable back to them. No member of the cell could be associated with a firearm in any way, shape

or form. This was vital to the future of the cell. Dinaal knew he had to take it extremely seriously.

It was the Colombian who managed to achieve this level of secret acquisition, quite by chance. He stole the weapon from the

military without them knowing who had done it. He was driving towards a country road checkpoint late one night, common enough

just about anywhere around the Colombian capital, and the barrier was up. He was waved through by a single soldier and noticed

a dozen or so others asleep, weapons out of hands. Instantly inspired, he drove for about another hundred metres, around a

couple of bends and pulled the car off the road. He crept back through the bush on foot. He took not only a rifle but a pouch

full of magazines.

After detailed questioning of the Colombian, Dinaal was satisfied that security had been maintained and that it would remain

so as long as the weapon was never found in their possession and they kept it hidden until they needed it.

Finally the night of the task arrived. The seven men climbed into a van and they drove into the city. The van belonged to

Dinaal, a second-hand Transit with windows at the front and in the back doors only. It was rusty in places and looked well

worn but Dinaal ensured the engine was always in good condition. The Colombian was at the wheel. They kept to the highways

and after a while they hit Calle 17 and headed into the much less populated agricultural area to the north-west. The traffic

had been heavy in the city but as soon as they turned on to the farm road it disappeared. The surface of the road was hard-packed

crushed stone that wound through small, cultivated fields. A handful of farm houses were dotted about. The land was as flat

as a billiard table in every direction.

Less than a kilometre along the lane, the vehicle turned into an even narrower track and came to a stop under some trees,

which provided complete cover from the moonlight. The Colombian turned off the lights and the engine.

The two Pakistani men climbed out of the back of the van and skipped into the bushes. They looked at the few houses in sight,

their lights on inside. Otherwise they couldn’t see any sign of life.

Dinaal hardly took his eyes off his watch. The others waited quietly and patiently. ‘Let’s go,’ he said finally.

The double doors at the back opened and the men climbed out. Two of them were carrying a long wooden box. Dinaal and the Colombian

driver joined them.

‘You have three minutes to set up,’ Dinaal said.

One of the Saudis and the Indonesian climbed over a low, wooden fence and took the box that was handed to them. Then they all hurried along the edge of a ploughed field. The ground began to slope away a little as they reached the end of the

field, where they stopped. Beyond them they could see a wide trough of marshy water that reflected the moonlight.

‘One minute,’ said Dinaal.

They placed the box on the ground and opened it. Inside was the rifle, a standard 5.56mm ball Galil IMI. The Saudi who had

been elected weapon preparer lifted the weapon out of the box. He was handed a magazine and he pushed it into its housing,

cocked the breach that loaded the chamber and handed the weapon to the Indonesian, who was standing ready and waiting to receive

it. He was short and stocky, low centre of gravity. He took it, placed the stock into his shoulder and looked directly at

Dinaal.

‘That way,’ Yusef said, holding his arm out. The Indonesian adjusted his position so that he was aiming the rifle into the

sky in the direction indicated.

‘Hold him,’ Dinaal hissed at the Saudi.

The man took a tight hold around the Indonesian’s waist.

‘Safety catch,’ Dinaal said.

The Indonesian removed the safety catch.

Dinaal searched the skies behind them, in the opposite direction to the aim of the rifleman.

After about fifteen seconds they could all hear the distant sound of an approaching aircraft.

The rifle pair didn’t move, they just remained focused skywards, their backs to the oncoming aircraft, while Dinaal and the

others stared into the black star-covered sky.

‘There,’ said the Colombian, finding a couple of tiny, piercing lights moving together through the thousands of stars. A large,

commercial passenger plane soon took shape, increasing in size as it descended directly towards them, its headlights searching

ahead.

Dinaal glanced at his gun team, who remained in position. ‘Get ready,’ he said.

The Indonesian regripped the weapon that he held tightly into his shoulder. His number two squeezed him slightly harder, arms

clamped around the man.

The scream of the jet engines grew rapidly louder as the craft began to fill the sky. Dinaal could see the cockpit windows

now. He felt a fleeting satisfaction with his timing and positioning perfectly beneath the large craft’s flight path. As it

roared overhead the Indonesian aimed at its underbelly, which was not difficult – it practically filled his vision.

‘Now!’ cried Dinaal above the deafening shriek of the turbines.

The Indonesian fired a single shot. The report, like Dinaal’s shouted command, was consumed by the intense high-pitched whine

of the big bird’s huge engines.

The Indonesian lowered the barrel but his partner still held him and they all stared at the tail of the thundering airliner

as it continued to descend towards the bright parallel lines of airfield approach lights in the field before the runway.

‘Quickly!’ Dinaal shouted.

The Indonesian shoved his partner away and placed the gun back inside the wooden box. They picked it up and hurried along

the field to the fence, which they scurried over. The two lookouts held the doors of the van open for them. The team stepped

up and inside and pulled the doors closed. Dinaal joined the driver in the front and the engine burst to life. The Colombian

reversed the vehicle out of the narrow track on to the stone lane, turned on the lights and drove them back the way they had

come.

A line of suitcases of various shapes and colours oozed from beneath a curtain of twisted black rubber strips. They lay on

a well-worn conveyor track that looped through the drab and humid baggage hall of Bogota International Airport. A porter plucked one of them from the line, placed it on a rickety trolley and followed

a tall, casually dressed man to the customs desk. The man showed the official his diplomatic passport and was promptly ushered

through to the arrivals hall.

On the street outside, the Englishman was led to a smart bulletproof limousine. He climbed inside, his suitcase was placed

in the trunk and the vehicle drove off.

Forty-five minutes later it arrived at the entrance to the British Embassy, where it passed through several layers of robust

security to gain entry. A few minutes after that the man wheeled his suitcase into a large second-floor office in the three-thousand-square-metre

building. The room was well appointed, had everything such an office should have, including a big ornate lump of a desk. An

older man in a dark suit sat behind it.

‘Ah. He has arrived,’ the man behind the desk said, grinning and getting to his feet. ‘Good flight?’

‘Bearable,’ the Englishman said, letting go of his suitcase and placing a laptop bag on a chair. ‘You’ve caught a bit of sun

since I left.’

‘A round of golf with the American Ambassador.’

‘Did you win?’

‘Tried hard not to but his putting was frightful. Whisky?’

‘Yes, but this one’s on me. And I have a treat for you.’

The tall Englishman placed his suitcase on a chair and opened it. He took out a couple of shirts and looked at them. They

were wet in his hands. He put them down and picked up the wooden box nested in the centre of the case. The contents of the

box tinkled, made the sound of broken glass. The man turned it in his hands and an amber-coloured liquid dribbled from a hole

in the side of the box.

‘Oh dear,’ the old embassy man said as he approached. ‘What a waste.’

With his index finger, the Englishman probed the two neat holes on either side of the wooden box. It led him to investigate

the lid of the suitcase. It had a neat hole in the centre. He lifted the case to discover a corresponding hole the other side.

‘It’s a bloody bullet hole,’ he muttered.

‘So it is,’ the other man said, looking quizzically at his colleague.

Stratton sat in complete darkness on a grey rocky slope in a treeless, moonscape wilderness. He was wearing an insulated jacket

and hard-wearing trousers, heavy boots and a thick goat-hair scarf wrapped around his neck to keep out the chilly night air.

He looked like he had been camping in the outback for days without a clean-up.

He was in a comfortable position, his back against a rock, knees bent up in front of him, elbows resting on them, supporting

a thermal imager in his hands. He was looking through the electronic optical device at a house half a mile away. It was one

dwelling among a cramped collection of them, practically every one small, single-storey and built of mud bricks or concrete

blocks. He slowly scanned the village, pausing each time the imager picked up a human form.

A mile beyond the village the land abruptly ended in a dead-straight horizontal line across his entire panorama, beyond it

a vast black ocean and a lighter cloudy sky.

Stratton lowered the optic, letting it hang from a strap around his neck. He picked up a large pair of binoculars and took

another view of the area. There was enough light coming from some of the houses for the glasses to be effective. Headlights

suddenly appeared beyond the village, coming from the direction of the highway that followed the coastline. He shifted the

binoculars on to them.

‘Vehicles approaching from the south-east,’ a voice said over Stratton’s earpiece. ‘Looks like two Suburbans.’ The communications were encrypted and scrambled should anyone else try to

listen in.

‘Roger,’ Stratton said as he watched the two pairs of headlights bump along a gravel road. The vehicles drove into the village,

lights occasionally flashing skywards as they bumped over the heavily rutted ground. They came to a halt outside the house

Stratton had been watching.

He switched back to the thermal imager and focused on the lead vehicle. He could see the bright white of the car’s brake discs

and exhausts. He watched as the Suburban’s rear doors opened. A couple of men climbed out. The thermal imagers graded them

down the scale from the superheated components of the car. The bodies were lighter than the buildings behind them and the

ground under their feet. Stratton could see the men’s hands and their heads, brighter than their clothing. Both men were carrying

rifles, the cool metal almost black in their white hands, but just as visible because of the contrast.

One of the men went to the front door of the house. As he approached, it opened and two men came outside. There appeared to

be an exchange of words. One of the men from the house walked to the Suburban and looked to have a conversation with someone

in the back.

‘Do you have eyes on?’ the voice asked over Stratton’s earpiece.

‘Yes, though I can’t identify anyone. But it’s the right time, the right place and they look pretty cautious,’ Stratton replied.

‘I’d say it’s safe to assume our man’s there.’

‘Enough to do the snatch?’

‘Why not? It’s like fishing. If we don’t like what we catch, we can always throw it back.’

‘Is that what you normally do?’

‘If there was a normal way of doing things like this, everyone would be doing it.’

Stratton picked up a large reflector drum lens on a tripod with a device attached to the optic and looked through it. Because

the image was highly magnified, it took him a few seconds to find the vehicles. He saw a man climb out of the back of the

lead Suburban and talk with the one from the house. Stratton pushed a button on the device, which took several still recordings

of the man. They were all of his head but more of the back than the front or sides.

The man walked towards the house. Just before going in he turned to the vehicles as if someone had called to him. Stratton

quickly recorded several images of the man before he turned and entered the house.

Stratton viewed the images he’d taken and selected several of the man’s face. He downloaded the images on to the satellite

phone attached to the lens. He scrolled through the address book, selected a number and hit send. A few seconds later a window

confirmed that the file had been sent.

He took up the thermal imager again, carried on scanning the house and the two vehicles. The two armed men stood off a couple

of metres from the SUVs. The engines of the Suburbans were still running, their exhausts bright white on the imager.

‘If it makes you feel any better,’ Stratton said, ‘I just sent London some images of a possible. They should be able to confirm.’

Less than a minute later the satphone gave off a chirp and he looked at the screen message: Image 3. Target confirmed.

Stratton disconnected the drum lens and put it in a backpack. ‘Hopper?’

‘Send,’ said the voice.

‘London has replied. If we catch this fish, we can keep it. I’ll see you at the RV in two.’

‘Roger that,’ Hopper replied.

Stratton got to his feet, tied up the pack and pulled it on to his strong shoulders. He checked the ground around him, pocketed

the wrapper from an energy bar he had eaten and searched for anything else. He made a three-hundred-and-sixty-degree scan

of his surroundings using the imager. It picked up nothing save a few goats a couple of kilometres away. He wondered what

the bloody things ate. It didn’t seem possible that anything could grow in this barren land.

He headed down the gravelly incline into a gully that took him out of sight of the village. Stratton dug a cellphone from

his pocket and hit a memory dial.

‘Prabhu? Stratton. We’re in business. We’re towards you now, OK?’

Then he pocketed the phone and clambered on down a steep channel to a stony track barely visible in the low light. He paused

to look around and listen. The sound of stones shingling downhill came from the slope opposite him. He continued walking and

watched the shadowy outline of a man grow clearer as it made its way down the rise towards him.

The man joined him on the track and they walked alongside each other. The man was a similar age and build to Stratton, his

lighter hair cut short. ‘That was a pleasant few hours,’ Hopper said. ‘I would like to have seen the sunset though. Could

you see it from where you were?’

‘Not quite.’

‘If the demand for gravel ever equals oil, Yemen will make a bloody fortune,’ said Hopper. ’Never seen a country with so much

dry rubble. The entire place looks like it’s been bulldozed. A few trees would help. I don’t know how the bloody goats manage.

You could scratch around here all day and not find anything to eat. And water? The riverbeds must have water in them no more

than a couple of days a year.’

Stratton listened to his partner talk. Hopper was a passionate man at heart to be sure. He felt sympathetic to people whose

lifestyle he judged to be of a lower quality than his own. And he assumed that if they could, they would like to live the way he did. It made Stratton feel cold and unconcerned by comparison and Stratton

didn’t regard himself as particularly cold. He didn’t resent Hopper for it though. Nor did he think the man was soft. But

the way Hopper talked, with his emphasis on human kindness, it was a tad over the top, as well as being a potential weakness

in their business. Yet that was Hopper. Stratton had known him on and off for ten years or so. He had worked with him hardly

at all and knew him more socially than anything else back in Poole.

‘You happy with this next phase?’ Stratton asked.

‘Yep. No probs. You talked to Prabhu?’

‘He’s on his way to the RV. Have you done a snatch like this before?’

‘A few. One in Iraq. A handful in Afghanistan.’

‘This should be easier. I don’t expect the target to be as twitchy here. This is generally a quiet neighbourhood.’

‘You operated in Yemen before?’

‘Did a small task in Aden a couple years ago,’ said Stratton. ‘I’ve never been here before.’

Hopper checked his watch. ‘Helen’ll be putting the boys to bed about now,’ he said. ‘We usually let ’em have a late night

Saturdays.’

Stratton had met Hopper’s wife a few times. At the occasional family functions the service ran. She was nowhere near as chatty

as her husband, certainly not with Stratton at least. But that standoff attitude was not unusual. He had a good idea what

most of the wives thought about him. He was single for one. And he never brought a girl to the camp gigs, which suggested

he did not have a steady girlfriend. There was ample evidence to prove that he had normal tastes when it came to females.

It was just that nobody he hooked up with appeared to last very long. Add that to his reputation as a specialised operative,

exaggerated or otherwise, and most of the wives, other than those of his closest friends, put up a barrier when he was around.

But Stratton never felt completely comfortable operating alongside men like Hopper because they brought their families with

them. Hopper was always thinking about them or talking about them in conversation. He seemed unable to disconnect while away

on ops. Hopper never saw it as a disadvantage being a family man as well as an SBS operative. He regarded himself as pure

special forces. He only talked to civilians beyond casual exchanges if he had to. He viewed them as potential security leaks.

All of his friends were serving or former military personnel.

All of which meant several things to Stratton. Hopper would be fine and he would do the job well enough. But he would have

preferred it if Hopper had not been chosen for this operation. He was better suited to large-scale ops. But at the end of

the day Hopper had a reputation for being reliable, for being steady, and Stratton had no doubt he would do well.

‘We weren’t talking the day I left for here,’ Hopper went on. ‘Had a bit of a row. Not the best thing when you’re off on an

op. By the time I get home it will all have blown over. Helen doesn’t hold on to things like that for long. You’ve met Helen

before, haven’t you?’

‘Yes.’

‘Course you have. That last service family barbeque. I never associate you with those kinds of bashes.’

‘I think I got back from somewhere that day and just happened to be there.’

‘That would explain it.’

‘We’re getting close to the RV,’ Stratton said. He wasn’t concerned about being overheard. They were still a long way from

the village. But the family chat was getting him out of the right frame of mind. It didn’t feel right to be talking about

Hopper’s family life. It was precisely the reason why he didn’t like working with married fads.

They came to a broader track that connected the coastal highway with the village. A short distance further along they hit a track junction, the other route leading way up into the hills.

A narrow wadi ran alongside the track and through the junction at that point. Stratton stepped down into it. Hopper joined

him.

‘This is ideal,’ Hopper said. ‘Far enough away from the village and the highway.’

The air was still. Both men heard the quiet sound of boots on loose stones and they looked along the track that led up into

the hills to see a figure approaching along it. The man was short and solid-looking and carrying a small backpack. He stopped

on the edge of the wadi and squatted on his haunches with an economy of energy.

‘Ram ram, Prabhu,’ Stratton said, by way of greeting.

‘Hajur, sab,’ Prabhu replied.

‘Sabai tic cha?’ Stratton asked. It was more of a formality than anything else because Prabhu would have warned him as soon

as something was not OK.

‘Tic cha,’ Prabhu replied in his calm, easy manner, a hint of a smile on his lips. He had a flat, ageless face, short dark

hair. He was a former British Gurkha officer and had completed twenty-four years in the battalion, rising through . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...